by Shawn Crawford

For a Baptist, the Bible exists like gravity. Not believing in gravity will not change the outcome if you step off a building; not believing the Bible will not change the consequences if you ignore its precepts and commands. Both are laws of nature, fixed and unchanging.

For a Baptist, the Bible exists like gravity. Not believing in gravity will not change the outcome if you step off a building; not believing the Bible will not change the consequences if you ignore its precepts and commands. Both are laws of nature, fixed and unchanging.

To really understand what it means to be Baptist, you must understand the unique place the Bible holds in every facet of life. The central reality of existence is not God but rather the words he left behind to guide our decisions, our relationships, and our behavior. Baptists create a world that revolves around The Book to a degree that can easily be termed idolatry. In a religion that shuns all iconography, the Bible becomes the one object that can be revered. But not because it symbolizes the presence of God’s word among us: it is God’s Word, infallible and unchangeable. The Southern Baptist statement of beliefs, The Baptist Faith and Message, begins with the Bible, not God. It states in part, “[The Bible] has God for its author, salvation for its end, and truth, without any mixture of error, for its matter.”

The close reading of scripture allowed you to extract the meaning God intended. That meaning could be discovered, not interpreted, and it could be agreed upon and then applied to how you lived your daily life: “Thy word is a lamp unto my feet and light unto my path” (Psalm 119.105). The Book of Psalms is in the middle of the Bible, and can best be translated “praises” or “songs” from the Hebrew. Psalm 119 is the longest chapter of the Bible, clocking in at 176 verses. Writers of Psalms often used an acrostic method employing the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Psalm 119 is a tour de force, with each of eight verses in a stanza opening with the same letter, moving through all twenty-two letters of the alphabet.

As you might have guessed, I spent a lot of time with the Bible. Read more »

Few topics have captured the attention of the internet literati more than the topic of Jordan B. Peterson. Peterson,

Few topics have captured the attention of the internet literati more than the topic of Jordan B. Peterson. Peterson,

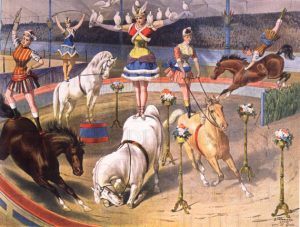

What follows is part of a collaborative project between a historian and a student of medicine called “The Temperature of Our Time.” In forming diagnoses, historians and doctors gather what Carlo Ginzburg has called “small insights”—clues drawn from “concrete experience”—to expose the invisible: a forensic assessment of condition, the origins of an idiopathic illness, the trajectory of an idea through time. Taking the temperature of our time means reading vital signs and symptoms around a fixed theme or metaphor—in this case, the circus.

What follows is part of a collaborative project between a historian and a student of medicine called “The Temperature of Our Time.” In forming diagnoses, historians and doctors gather what Carlo Ginzburg has called “small insights”—clues drawn from “concrete experience”—to expose the invisible: a forensic assessment of condition, the origins of an idiopathic illness, the trajectory of an idea through time. Taking the temperature of our time means reading vital signs and symptoms around a fixed theme or metaphor—in this case, the circus. There is a famous exchange in Casablanca between Rick (Humphrey Bogart) and Captain Renault (Claude Rains):

There is a famous exchange in Casablanca between Rick (Humphrey Bogart) and Captain Renault (Claude Rains):

Translation is the silent waiter of linguistic performance: It often gets noticed only when it knocks over the serving cart. Sometimes these are relatively minor errors — a ham-handed rendering of an author’s prose, the sort of thing a book reviewer might skewer with an acid pen.

Translation is the silent waiter of linguistic performance: It often gets noticed only when it knocks over the serving cart. Sometimes these are relatively minor errors — a ham-handed rendering of an author’s prose, the sort of thing a book reviewer might skewer with an acid pen. The theoretical physicist John Wheeler once used the phrase “great smoky dragon” to describe a particle of light going from a source to a photon counter. “The mouth of the dragon is sharp, where it bites the counter. The tail of the dragon is sharp, where the photon starts,” Wheeler wrote. The photon, in other words, has definite reality at the beginning and end. But its state in the middle — the dragon’s body — is nebulous. “What the dragon does or looks like in between we have no right to speak.”

The theoretical physicist John Wheeler once used the phrase “great smoky dragon” to describe a particle of light going from a source to a photon counter. “The mouth of the dragon is sharp, where it bites the counter. The tail of the dragon is sharp, where the photon starts,” Wheeler wrote. The photon, in other words, has definite reality at the beginning and end. But its state in the middle — the dragon’s body — is nebulous. “What the dragon does or looks like in between we have no right to speak.” The endgame of the war in Syria is likely to come down to the northwestern province of Idlib, on the Turkish border, where some 2.3 million people are now trapped. As Russian-Syrian forces now finish retaking the smaller southwestern province of Daraa, Idlib will be the last significant enclave in anti-government hands. If Russian-Syrian forces resume pummeling the city and surrounding area from the air, its civilians could face the horrible choice of bunkering in place or desperately trying to cross the Turkish border, which has been effectively closed since 2015.

The endgame of the war in Syria is likely to come down to the northwestern province of Idlib, on the Turkish border, where some 2.3 million people are now trapped. As Russian-Syrian forces now finish retaking the smaller southwestern province of Daraa, Idlib will be the last significant enclave in anti-government hands. If Russian-Syrian forces resume pummeling the city and surrounding area from the air, its civilians could face the horrible choice of bunkering in place or desperately trying to cross the Turkish border, which has been effectively closed since 2015.

This is a story about a book that just kept selling, catching publishers, booksellers and even its author off guard. In seeking to understand the reasons for the book’s unusually protracted shelf life, we uncover important messages about our moment in history, about the still-vital place of reading in our culture, and about the changing face of publishing. The book is

This is a story about a book that just kept selling, catching publishers, booksellers and even its author off guard. In seeking to understand the reasons for the book’s unusually protracted shelf life, we uncover important messages about our moment in history, about the still-vital place of reading in our culture, and about the changing face of publishing. The book is  The suffragist heroes Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony seized control of the feminist narrative of the 19th century. Their influential history of the movement still governs popular understanding of the struggle for women’s rights and will no doubt serve as a touchstone for commemorations that will unfold across the United States around the centennial of the 19th Amendment in 2020.

The suffragist heroes Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony seized control of the feminist narrative of the 19th century. Their influential history of the movement still governs popular understanding of the struggle for women’s rights and will no doubt serve as a touchstone for commemorations that will unfold across the United States around the centennial of the 19th Amendment in 2020. Plants could soon provide our electricity. In a small way they already are doing that in research labs and greenhouses at project Plant-e — a university and commercially sponsored research group at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. The Plant Microbial Fuel Cell from Plant-e can generate electricity from the natural interaction between plant roots and soil bacteria. It works by taking advantage of the up to 70 percent of organic material produced by a plant’s

Plants could soon provide our electricity. In a small way they already are doing that in research labs and greenhouses at project Plant-e — a university and commercially sponsored research group at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. The Plant Microbial Fuel Cell from Plant-e can generate electricity from the natural interaction between plant roots and soil bacteria. It works by taking advantage of the up to 70 percent of organic material produced by a plant’s  There are books that enter your life before their time; you can acknowledge their beauty and excellence, and yet walk away unchanged. This was how I first read Elizabeth Hardwick’s “Sleepless Nights,” after it was recommended in David Shields’ “Reality Hunger,” a thrilling manifesto that tries to make the case that our contemporary world is no longer well represented by realist fiction. While I loved “Sleepless Nights” on that first read — it is brilliant, brittle and strange, a book unlike any preconceived notion I had of what a novel could be — I moved on from it easily. I’ve lived two thousand and some odd days since, read hundreds of other books and published three of my own, all in a bright, hot landscape of somewhat-realist fiction.

There are books that enter your life before their time; you can acknowledge their beauty and excellence, and yet walk away unchanged. This was how I first read Elizabeth Hardwick’s “Sleepless Nights,” after it was recommended in David Shields’ “Reality Hunger,” a thrilling manifesto that tries to make the case that our contemporary world is no longer well represented by realist fiction. While I loved “Sleepless Nights” on that first read — it is brilliant, brittle and strange, a book unlike any preconceived notion I had of what a novel could be — I moved on from it easily. I’ve lived two thousand and some odd days since, read hundreds of other books and published three of my own, all in a bright, hot landscape of somewhat-realist fiction.