Omar Ali at Brown Pundits:

Pakistan heads to the polls on July 25th. I happen to be in the middle of a move, so I have not been posting much but a short note on the election is certainly due. Back in 2013 Pakistan had its first peaceful democratic transfer of power and it looked like some sort of democracy was finally taking root, with the military still exercising disproportionate influence but with an elected government running most of the country according to its own priorities. Unfortunately, the trend line has since reversed and done so in spectacular fashion. There are many theories about why this particular reversal happened, with some people blaming the party in power (the nominally right of center PMLN) and others the overweening ambitions of GHQ (*General Headquarters. The army). Whatever the triggers, it seems that at some point the army high command decided that it could not coexist with Mian Nawaz Sharif and his politically ambitious daughter (Maryam Nawaz Sharif) and for the last year and a half the army, primarily acting through its intelligence agencies (for the rough stuff) and ISPR (the PR wing of the army, now expanded into a vast public relations operation with a serving general in charge) has been on a crusade against the PMLN in general and Mian Nawaz Sharif (MNS) and his daughter in particular.

Pakistan heads to the polls on July 25th. I happen to be in the middle of a move, so I have not been posting much but a short note on the election is certainly due. Back in 2013 Pakistan had its first peaceful democratic transfer of power and it looked like some sort of democracy was finally taking root, with the military still exercising disproportionate influence but with an elected government running most of the country according to its own priorities. Unfortunately, the trend line has since reversed and done so in spectacular fashion. There are many theories about why this particular reversal happened, with some people blaming the party in power (the nominally right of center PMLN) and others the overweening ambitions of GHQ (*General Headquarters. The army). Whatever the triggers, it seems that at some point the army high command decided that it could not coexist with Mian Nawaz Sharif and his politically ambitious daughter (Maryam Nawaz Sharif) and for the last year and a half the army, primarily acting through its intelligence agencies (for the rough stuff) and ISPR (the PR wing of the army, now expanded into a vast public relations operation with a serving general in charge) has been on a crusade against the PMLN in general and Mian Nawaz Sharif (MNS) and his daughter in particular.

More here.

It is difficult to understand the genocide because the genocide occurred not in a secret place, but in full view of the observing world. In 1993, Lieutenant General Philippe Morillon, the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) Commander in Bosnia-Herzegovina, came to Srebrenica and, after seeing the death camp circumstances of the civilians living under the siege, declared that Srebrenica was under the protection of the UN. In April 1993, the UN Security Council, adopted Resolution 819 which formally declared Srebrenica a UN “safe area,” following after Morillon’s declaration, and sent UNPROFOR soldiers from Canada, and later the Netherlands to the town. As part of the demilitarization agreement, military commanders defending Srebrenica agreed to turn over their heavy arms in exchange for UN protection. As early as April 1993, Ambassador Diego Arria, Permanent Representative of Venezuela to the UN Security Council, described the situation in Srebrenica as a “slow-motion genocide under the protection of the UN forces” In July 1995, Srebrenica—under the protection of UN forces—became a fast-motion genocide.

It is difficult to understand the genocide because the genocide occurred not in a secret place, but in full view of the observing world. In 1993, Lieutenant General Philippe Morillon, the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) Commander in Bosnia-Herzegovina, came to Srebrenica and, after seeing the death camp circumstances of the civilians living under the siege, declared that Srebrenica was under the protection of the UN. In April 1993, the UN Security Council, adopted Resolution 819 which formally declared Srebrenica a UN “safe area,” following after Morillon’s declaration, and sent UNPROFOR soldiers from Canada, and later the Netherlands to the town. As part of the demilitarization agreement, military commanders defending Srebrenica agreed to turn over their heavy arms in exchange for UN protection. As early as April 1993, Ambassador Diego Arria, Permanent Representative of Venezuela to the UN Security Council, described the situation in Srebrenica as a “slow-motion genocide under the protection of the UN forces” In July 1995, Srebrenica—under the protection of UN forces—became a fast-motion genocide. But Alcibiades, like Byron, clearly had that indefinable something. One catches a glimpse of it in the unforgettable last scene of Plato’s Symposium, when he crashes into the room, blind drunk, flirting with everything on legs, shouting about his love for Socrates. Thucydides captures it in his report of Alcibiades’s speech whipping up the Athenian assembly to vote for the disastrous Sicilian expedition of 415 BC – an extraordinary stew of egotistic bragging (about how successful his racehorses are), mendacious demagoguery and brilliantly acute strategic thinking. The unwashed Athenian masses, not usually prone to atavistic toff-grovelling, absolutely adored him: when Alcibiades finally returned to Athens in 407 BC after eight years of exile, sailing coolly into Piraeus on a ship with purple sails, they welcomed him back with paroxysms of joy.

But Alcibiades, like Byron, clearly had that indefinable something. One catches a glimpse of it in the unforgettable last scene of Plato’s Symposium, when he crashes into the room, blind drunk, flirting with everything on legs, shouting about his love for Socrates. Thucydides captures it in his report of Alcibiades’s speech whipping up the Athenian assembly to vote for the disastrous Sicilian expedition of 415 BC – an extraordinary stew of egotistic bragging (about how successful his racehorses are), mendacious demagoguery and brilliantly acute strategic thinking. The unwashed Athenian masses, not usually prone to atavistic toff-grovelling, absolutely adored him: when Alcibiades finally returned to Athens in 407 BC after eight years of exile, sailing coolly into Piraeus on a ship with purple sails, they welcomed him back with paroxysms of joy. In the Chester Beatty Library, there are books made entirely of jade. There are picture scrolls featuring calligraphy by the brother of the Japanese emperor. There are papyrus codices that constitute some of the few surviving texts of Manichaeism, a religion of darkness and light that rivaled Christianity in scale until its last believers died out in fourteenth-century China. There are Armenian hymnals, Renaissance catalogues of war machines, and monographs on native Australian fauna. There is all of this and more—thousands and thousands of other works diverse in period and place of origin, waiting for human eyes. And yet as I walk through the galleries, as I survey the cases of books safe behind their glass, it occurs to me that if a book is a thing meant to be read, then in a certain sense, these objects have lost their function to all but the scholarly epigraphists, backs bent in the private study room. And yet far from becoming something less because of this, the books on display have become something more.

In the Chester Beatty Library, there are books made entirely of jade. There are picture scrolls featuring calligraphy by the brother of the Japanese emperor. There are papyrus codices that constitute some of the few surviving texts of Manichaeism, a religion of darkness and light that rivaled Christianity in scale until its last believers died out in fourteenth-century China. There are Armenian hymnals, Renaissance catalogues of war machines, and monographs on native Australian fauna. There is all of this and more—thousands and thousands of other works diverse in period and place of origin, waiting for human eyes. And yet as I walk through the galleries, as I survey the cases of books safe behind their glass, it occurs to me that if a book is a thing meant to be read, then in a certain sense, these objects have lost their function to all but the scholarly epigraphists, backs bent in the private study room. And yet far from becoming something less because of this, the books on display have become something more. “Castle Rock,” Hulu’s longform series ode to

“Castle Rock,” Hulu’s longform series ode to  In early 2014

In early 2014 The Hague, September 2016. The speech from the UN high commissioner for human rights was not expected to ruffle feathers. A mild appeal to our better angels and then back to the canapés—traditionally, as one UN speechwriter puts it, “we don’t use adjectives, we don’t name names.”

The Hague, September 2016. The speech from the UN high commissioner for human rights was not expected to ruffle feathers. A mild appeal to our better angels and then back to the canapés—traditionally, as one UN speechwriter puts it, “we don’t use adjectives, we don’t name names.” Benjamin Moser in The New Yorker:

Benjamin Moser in The New Yorker:

W

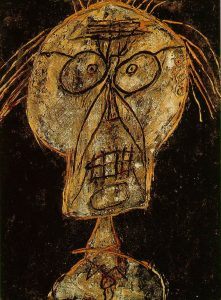

W By conceiving the notion of art brutin a Europe devastated by the Second World War, French artist Jean Dubuffet questioned the underlying pretense behind the processes of artistic legitimization, dispossessing those authorities empowered to legislate in the art world. He also insisted on the flexible nature of definitions, maintaining that art brutcould incessantly evolve depending on the context of its emergence, knowing that the norm and the margins are perpetually reassessed. Without an art movement or identifiable style, art brut is not a category, but an evolving critical concept. Above all, as observed Céline Delavaux, Dubuffet likely proposed a singular, even poetic and literary way of thinking about art, “It is in the absence of the voice of the madman, the excluded, the uneducated, that his radically subjective art discourse was invented.”

By conceiving the notion of art brutin a Europe devastated by the Second World War, French artist Jean Dubuffet questioned the underlying pretense behind the processes of artistic legitimization, dispossessing those authorities empowered to legislate in the art world. He also insisted on the flexible nature of definitions, maintaining that art brutcould incessantly evolve depending on the context of its emergence, knowing that the norm and the margins are perpetually reassessed. Without an art movement or identifiable style, art brut is not a category, but an evolving critical concept. Above all, as observed Céline Delavaux, Dubuffet likely proposed a singular, even poetic and literary way of thinking about art, “It is in the absence of the voice of the madman, the excluded, the uneducated, that his radically subjective art discourse was invented.” H

H Imagine you’re the president of a European country. You’re slated to take in 50,000 refugees from the Middle East this year. Most of them are very religious, while most of your population is very secular. You want to integrate the newcomers seamlessly, minimizing the risk of economic malaise or violence, but you have limited resources. One of your advisers tells you to invest in the refugees’ education; another says providing jobs is the key; yet another insists the most important thing is giving the youth opportunities to socialize with local kids. What do you do? Well, you make your best guess and hope the policy you chose works out. But it might not. Even a policy that yielded great results in another place or time may fail miserably in your particular country under its present circumstances. If that happens, you might find yourself wishing you could hit a giant reset button and run the whole experiment over again, this time choosing a different policy. But of course, you can’t experiment like that, not with real people.

Imagine you’re the president of a European country. You’re slated to take in 50,000 refugees from the Middle East this year. Most of them are very religious, while most of your population is very secular. You want to integrate the newcomers seamlessly, minimizing the risk of economic malaise or violence, but you have limited resources. One of your advisers tells you to invest in the refugees’ education; another says providing jobs is the key; yet another insists the most important thing is giving the youth opportunities to socialize with local kids. What do you do? Well, you make your best guess and hope the policy you chose works out. But it might not. Even a policy that yielded great results in another place or time may fail miserably in your particular country under its present circumstances. If that happens, you might find yourself wishing you could hit a giant reset button and run the whole experiment over again, this time choosing a different policy. But of course, you can’t experiment like that, not with real people. In the largest genetics study ever published in a scientific journal, an international team of scientists on Monday

In the largest genetics study ever published in a scientific journal, an international team of scientists on Monday