Jack Segelstein in The Atlantic:

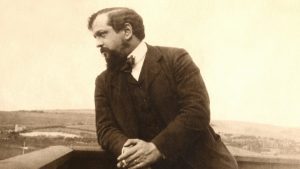

In 1889, Achille-Claude Debussy, then in his mid-20s, was one of 30 million people to walk through the iron arches of the newly completed Eiffel Tower. Throughout that year, the arches served as the grand entryway to the Exposition Universelle, a world’s fair celebrating the cultural, technological, and colonial prowess of France a century after the revolution. A stunning variety of sights greeted visitors: a sharpshooting Annie Oakley, some 16,000 ultramodern machines (housed in the largest indoor space ever constructed), and, of course, the Eiffel Tower itself, the world’s tallest and possibly most bizarre building at the time. But Debussy seems to have been most impressed by something he heard—the work of musicians from what was then French Indochina and is now Vietnam. More than 20 years later, he raved about the opera they performed, in which “a furious little clarinet directs the emotion, a gong organizes the terror … and that’s all! … Nothing but an instinctive need for art, needing ingenuity to satisfy; no hint of bad taste!”

As Stephen Walsh shows in Debussy: A Painter in Sound—published in 2018, 100 years after the composer’s death—Debussy craved this simplicity and directness, but he had trouble finding it in his own musical milieu. He admired older French music—its “clarity of expression, that precision and compactness of form”—but felt it had been corrupted by German influences. French color, lightness, and concision were at odds with the drama, severity, and burdensome forms of Bach, Beethoven, and, most recently, Richard Wagner.

More here.