Claudia Verhoeven in Taxis:

The testament Dostoevsky left his children was the parable of the Prodigal Son. He asked that it be read to them the night of the day he knew would be his last, and the late, great Joseph Frank judged that Dostoevsky had probably understood the whole of his life and all of his literature as having existed under the sign of this tale of “transgression, forgiveness, and redemption.”

The testament Dostoevsky left his children was the parable of the Prodigal Son. He asked that it be read to them the night of the day he knew would be his last, and the late, great Joseph Frank judged that Dostoevsky had probably understood the whole of his life and all of his literature as having existed under the sign of this tale of “transgression, forgiveness, and redemption.”

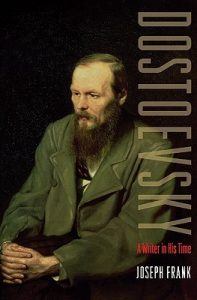

Anyone who loves Dostoevsky but not the effects of Dostoevshchina — the anger, annoyance, and nausea that come from overexposure to Dostoevsky’s God-peddling, Russo-mania, and digging in the dirt — that sentence will stab straight through the heart. Nine hundred pages into Frank’s Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time (Princeton University Press, 2009), Dostoevsky suddenly stands there transformed, not absolved of his sins exactly, but somehow free from Dostoevshchina. He stands there as a man, as a father, as a false prophet but a true believer, and above all as an author — and at that moment, you may freely renew your oath of allegiance to his artistic vision of unconditional love, however short of its fulfillment he himself so often fell.

It works in just the same way, in fact, as those moments in Dostoevsky’s texts that can lift even his most hostile readers into believing things forever foresworn. Take Dmitry Pisarev. Of all the literary critics belonging to the so-called “nihilist” camp in Alexander II’s reform-era Russia, this twenty-something was the most caustic and consequential. It was primarily Pisarev’s utilitarian logic that Dostoevsky had stuffed into Raskolnikov’s monomaniacal brain in order to prove that the “rational egoism” of the young generation could only end in cold-blooded murder. And apparently, when this very Pisarev got his hands on Crime and Punishment, he cried.

More here.