James Wolcott at the LRB:

As Atlas explains in The Shadow in the Garden, ‘Bellow had three sons: Greg, Adam, and Dan. He also had three disciples: James Wood, Leon Wieseltier and Martin Amis.’ Wood, the literary critic and novelist; Wieseltier, the former literary editor of the New Republic; and Amis, who, on the death of his father, Kingsley, declared to Bellow, ‘You’ll have to be my father now.’ Atlas: ‘These three were – I won’t say pseudo-sons, because their affection for Bellow was so deep as to be almost filial – but surrogate or substitute or perhaps alter-sons, whose love was uncomplicated by anger and the unruly demands of hereditary sons.’ And we can add a fourth alter-son, Atlas himself, who elsewhere in the book confides: ‘I had become accustomed to thinking of Bellow not only as a father figure but as a father, whose unconditional love – or at least forgiveness – I could count on no matter what I did.’ It’s difficult to imagine a less likely candidate for a chalice of unconditional love than Bellow (‘prickly’ was practically his middle name), but the whole surrogate dad/surrogate son business is a bewildering proposition, a sidebar of aberrant psychology; I’m not sure there’s anything comparable in American literary history.† I was a young-gun devotee of Mailer, who made possible my start in writing, but I never wanted him to file adoption papers. A patriarchal nimbus settled on Bellow in his later years that remains unique, inspiring, a little weird, a bit Holy Ghost. Attending Bellow’s readings at the 92nd Street Y was a form of religious observance. According to Atlas, ‘going to hear Bellow wasn’t a social event: it was an act of witness.’

As Atlas explains in The Shadow in the Garden, ‘Bellow had three sons: Greg, Adam, and Dan. He also had three disciples: James Wood, Leon Wieseltier and Martin Amis.’ Wood, the literary critic and novelist; Wieseltier, the former literary editor of the New Republic; and Amis, who, on the death of his father, Kingsley, declared to Bellow, ‘You’ll have to be my father now.’ Atlas: ‘These three were – I won’t say pseudo-sons, because their affection for Bellow was so deep as to be almost filial – but surrogate or substitute or perhaps alter-sons, whose love was uncomplicated by anger and the unruly demands of hereditary sons.’ And we can add a fourth alter-son, Atlas himself, who elsewhere in the book confides: ‘I had become accustomed to thinking of Bellow not only as a father figure but as a father, whose unconditional love – or at least forgiveness – I could count on no matter what I did.’ It’s difficult to imagine a less likely candidate for a chalice of unconditional love than Bellow (‘prickly’ was practically his middle name), but the whole surrogate dad/surrogate son business is a bewildering proposition, a sidebar of aberrant psychology; I’m not sure there’s anything comparable in American literary history.† I was a young-gun devotee of Mailer, who made possible my start in writing, but I never wanted him to file adoption papers. A patriarchal nimbus settled on Bellow in his later years that remains unique, inspiring, a little weird, a bit Holy Ghost. Attending Bellow’s readings at the 92nd Street Y was a form of religious observance. According to Atlas, ‘going to hear Bellow wasn’t a social event: it was an act of witness.’

more here.

In his languidly titled autobiography, “Life”, Keith Richards tells a story that captures something about the workplace culture of the Rolling Stones and his decades as the band’s guitarist. It’s 1984 and the Stones are in Amsterdam for a meeting (yes, even Keith Richards attends meetings). That night, Richards and Mick Jagger go out for a drink and return to their hotel in the early hours, by which time Jagger is somewhat the worse for wear. “Give Mick a couple of glasses, he’s gone,” Richards writes, scornfully. Jagger decides that he wants to see Charlie Watts, who has already gone to bed. He picks up the phone, calls Watts’s room and says, “Where’s my drummer?” There is no response from the other end of the line. Jagger and Richards have a few more drinks. Twenty minutes later, there’s a knock at the door. It is Watts, dressed in one of his Savile Row suits, freshly shaved and cologned. He seizes Jagger and shouts “Never call me your drummer again,” and delivers a sharp right hook to the singer’s chin.

In his languidly titled autobiography, “Life”, Keith Richards tells a story that captures something about the workplace culture of the Rolling Stones and his decades as the band’s guitarist. It’s 1984 and the Stones are in Amsterdam for a meeting (yes, even Keith Richards attends meetings). That night, Richards and Mick Jagger go out for a drink and return to their hotel in the early hours, by which time Jagger is somewhat the worse for wear. “Give Mick a couple of glasses, he’s gone,” Richards writes, scornfully. Jagger decides that he wants to see Charlie Watts, who has already gone to bed. He picks up the phone, calls Watts’s room and says, “Where’s my drummer?” There is no response from the other end of the line. Jagger and Richards have a few more drinks. Twenty minutes later, there’s a knock at the door. It is Watts, dressed in one of his Savile Row suits, freshly shaved and cologned. He seizes Jagger and shouts “Never call me your drummer again,” and delivers a sharp right hook to the singer’s chin. One of the core challenges of modern AI can be demonstrated with a rotating yellow school bus. When viewed head-on on a country road, a deep-learning neural network confidently and correctly identifies the bus. When it is laid on its side across the road, though, the algorithm believes—again, with high confidence—that it’s a snowplow. Seen from underneath and at an angle, it is definitely a garbage truck. The problem is one of context. When a new image is sufficiently different from the set of training images, deep learning visual recognition stumbles, even if the difference comes down to a simple rotation or obstruction. And context generation, in turn, seems to depend on a rather remarkable set of wiring and signal generation features—at least, it does in the human brain. Matthias Kaschube studies that wiring by building models that describe experimentally observed brain activity. Kaschube and his colleagues at the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies have found a host of features that stand in stark contrast to the circuits that engineers build: spontaneous activity and correlation, dynamic context generation, unreliable transmission, and straight-up noise. These seem to be fundamental features of what some call the universe’s most complex object—the brain.

One of the core challenges of modern AI can be demonstrated with a rotating yellow school bus. When viewed head-on on a country road, a deep-learning neural network confidently and correctly identifies the bus. When it is laid on its side across the road, though, the algorithm believes—again, with high confidence—that it’s a snowplow. Seen from underneath and at an angle, it is definitely a garbage truck. The problem is one of context. When a new image is sufficiently different from the set of training images, deep learning visual recognition stumbles, even if the difference comes down to a simple rotation or obstruction. And context generation, in turn, seems to depend on a rather remarkable set of wiring and signal generation features—at least, it does in the human brain. Matthias Kaschube studies that wiring by building models that describe experimentally observed brain activity. Kaschube and his colleagues at the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies have found a host of features that stand in stark contrast to the circuits that engineers build: spontaneous activity and correlation, dynamic context generation, unreliable transmission, and straight-up noise. These seem to be fundamental features of what some call the universe’s most complex object—the brain. In November, Politico

In November, Politico  Sometimes science is asking esoteric questions about the fundamental nature of reality. Other times, it just wants to solve a murder. Today’s guest, Raychelle Burks, is an analytical chemist at St. Edward’s University in Texas. Before becoming a full-time academic, she worked in a crime lab using chemistry to help police track suspects, and now she does research on building new detectors for use in forensic analyses. We talk about how the real world of forensic investigation differs from the version you see portrayed on CSI, and how real chemists use their tools to help law enforcement agencies fight crime. We may even touch on how criminals could use chemical knowledge to get away with their dastardly deeds.

Sometimes science is asking esoteric questions about the fundamental nature of reality. Other times, it just wants to solve a murder. Today’s guest, Raychelle Burks, is an analytical chemist at St. Edward’s University in Texas. Before becoming a full-time academic, she worked in a crime lab using chemistry to help police track suspects, and now she does research on building new detectors for use in forensic analyses. We talk about how the real world of forensic investigation differs from the version you see portrayed on CSI, and how real chemists use their tools to help law enforcement agencies fight crime. We may even touch on how criminals could use chemical knowledge to get away with their dastardly deeds. Was austerity the only possible response to the debt that many nations incurred after the global economic mess post 2008? The answer, if one looks at

Was austerity the only possible response to the debt that many nations incurred after the global economic mess post 2008? The answer, if one looks at I CAN TELL YOU the moment Roma revealed itself to be an indulgence, a liberal pose struck by a director whose infrequent output has helped build an unsupportable myth about his genius. It involves a trip to the movies, every director’s favorite shorthand for the magical, transporting power of cinema that saves them the trouble of having to conjure that power themselves.

I CAN TELL YOU the moment Roma revealed itself to be an indulgence, a liberal pose struck by a director whose infrequent output has helped build an unsupportable myth about his genius. It involves a trip to the movies, every director’s favorite shorthand for the magical, transporting power of cinema that saves them the trouble of having to conjure that power themselves. So it is that underneath Venturi and Brown’s extraordinary analysis of the decorated shed, Rome slowly appears in all its glory and monumentality. The facades of the great cathedrals move out to the street and become signs and ads of varying proportions (depending on the speed of the drivers); St. Peter’s vast square becomes a parking lot, the basilica a casino, and the side chapels so many dimly lit gambling salons under low ceilings. This is truly another form of historicism, the one we deserve; and it accommodates the theory. For the concept of the decorated shed explicitly tells us to do what we like with the space of the shed, to pray, sleep, give speeches, store our boxes, repair our cars: It is a form and not a content. Is it a structure, like Adam’s house in paradise? Perhaps, but then in that case, unlike the duck (where the ad or sign has been amalgamated with the monument itself), the structure is a tripartite one: the sign or facade, the parking lot, and then the basilica itself, the showcase or display space versus the back room (as Erving Goffman might have put it), where its unconscious, perhaps, or its hidden meanings (Freudian or ideological), its secret intentions or “programs,” live.

So it is that underneath Venturi and Brown’s extraordinary analysis of the decorated shed, Rome slowly appears in all its glory and monumentality. The facades of the great cathedrals move out to the street and become signs and ads of varying proportions (depending on the speed of the drivers); St. Peter’s vast square becomes a parking lot, the basilica a casino, and the side chapels so many dimly lit gambling salons under low ceilings. This is truly another form of historicism, the one we deserve; and it accommodates the theory. For the concept of the decorated shed explicitly tells us to do what we like with the space of the shed, to pray, sleep, give speeches, store our boxes, repair our cars: It is a form and not a content. Is it a structure, like Adam’s house in paradise? Perhaps, but then in that case, unlike the duck (where the ad or sign has been amalgamated with the monument itself), the structure is a tripartite one: the sign or facade, the parking lot, and then the basilica itself, the showcase or display space versus the back room (as Erving Goffman might have put it), where its unconscious, perhaps, or its hidden meanings (Freudian or ideological), its secret intentions or “programs,” live. Every death erases a uniqueness. But to say that there was no one on earth like Francine du Plessix Gray is to state a simple and obvious truth. There were three cultural—call them national—streams in her existence: French by birth and background, she was American in upbringing and in principles, and yet also deeply Russian in personal mythology and values and warmth. (Her Russian mother, Tatiana Yakovleva, was the great love of the poet Mayakovsky’s life, and Francine, by a rumor that both exasperated and entertained her, was acclaimed on her visits to Russia as his illegitimate daughter.) Francine, who died on Sunday, at the age of eighty-eight, was raised in what used to be called high or café society—Tatiana, whom she once

Every death erases a uniqueness. But to say that there was no one on earth like Francine du Plessix Gray is to state a simple and obvious truth. There were three cultural—call them national—streams in her existence: French by birth and background, she was American in upbringing and in principles, and yet also deeply Russian in personal mythology and values and warmth. (Her Russian mother, Tatiana Yakovleva, was the great love of the poet Mayakovsky’s life, and Francine, by a rumor that both exasperated and entertained her, was acclaimed on her visits to Russia as his illegitimate daughter.) Francine, who died on Sunday, at the age of eighty-eight, was raised in what used to be called high or café society—Tatiana, whom she once  Somewhere amid the sand dunes of the world’s oldest desert croons a soft voice: “It’s gonna take a lot to take me away from you.”

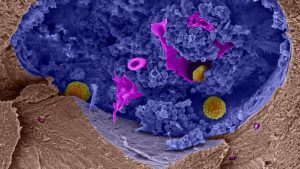

Somewhere amid the sand dunes of the world’s oldest desert croons a soft voice: “It’s gonna take a lot to take me away from you.” In multiple sclerosis (MS), a disease that strips away the sheaths that insulate nerve cells, the body’s immune cells come to see the nervous system as an enemy. Some drugs try to slow the disease by keeping immune cells in check, or by keeping them away from the brain. But for decades, some researchers have been exploring an alternative: wiping out those immune cells and starting over. The approach, called hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), has long been part of certain cancer treatments. A round of chemotherapy knocks out the immune system and an infusion of stem cells—either from a patient’s own blood or, in some cases, that of a donor—rebuilds it. The procedure is already in use for MS and other autoimmune diseases at several clinical centers around the world, but it has serious risks and is far from routine. Now, new results from a randomized clinical trial suggest it can be more effective than some currently approved MS drugs. “A side-by-side comparison of this magnitude had never been done,” says Paolo Muraro, a neurologist at Imperial College London who has also studied HSCT for MS. “It illustrates really the power of this treatment—the level of efficacy—in a way that’s very eloquent.”

In multiple sclerosis (MS), a disease that strips away the sheaths that insulate nerve cells, the body’s immune cells come to see the nervous system as an enemy. Some drugs try to slow the disease by keeping immune cells in check, or by keeping them away from the brain. But for decades, some researchers have been exploring an alternative: wiping out those immune cells and starting over. The approach, called hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), has long been part of certain cancer treatments. A round of chemotherapy knocks out the immune system and an infusion of stem cells—either from a patient’s own blood or, in some cases, that of a donor—rebuilds it. The procedure is already in use for MS and other autoimmune diseases at several clinical centers around the world, but it has serious risks and is far from routine. Now, new results from a randomized clinical trial suggest it can be more effective than some currently approved MS drugs. “A side-by-side comparison of this magnitude had never been done,” says Paolo Muraro, a neurologist at Imperial College London who has also studied HSCT for MS. “It illustrates really the power of this treatment—the level of efficacy—in a way that’s very eloquent.” Just over forty years ago the Supreme Court struck down race-based quotas in school admissions while also upholding the core tenets of affirmative action. In the landmark 1978 decision, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., singled out Harvard’s admissions program as an exemplar for achieving diversity and applauded the university’s own description of its policy, according to which the “race of an applicant may tip the balance in his favor just as geographic origin or a life spent on a farm may tip the balance in other candidates’ cases.” As the Supreme Court would later emphasize, such review considered race merely a “factor of a factor of a factor.”

Just over forty years ago the Supreme Court struck down race-based quotas in school admissions while also upholding the core tenets of affirmative action. In the landmark 1978 decision, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., singled out Harvard’s admissions program as an exemplar for achieving diversity and applauded the university’s own description of its policy, according to which the “race of an applicant may tip the balance in his favor just as geographic origin or a life spent on a farm may tip the balance in other candidates’ cases.” As the Supreme Court would later emphasize, such review considered race merely a “factor of a factor of a factor.” Among the world’s endangered minorities, Iranian Jews are an anomaly. Like their counterparts, their conditions categorically refute all the efforts their nation makes at seeming civilized and egalitarian—and so they embody, often without wanting to, all that is ugly and unjust about their native land.

Among the world’s endangered minorities, Iranian Jews are an anomaly. Like their counterparts, their conditions categorically refute all the efforts their nation makes at seeming civilized and egalitarian—and so they embody, often without wanting to, all that is ugly and unjust about their native land. Rosa Luxemburg thought Berlin could hide her. Five days into 1919, the Marxist revolutionary had helped to transform a wave of strikes and protests in the city into open revolution – the so-called Spartacist uprising. But by January 12, she was on the run, the revolt crushed by right-wing militia groups deployed by Germany’s new socialist government.

Rosa Luxemburg thought Berlin could hide her. Five days into 1919, the Marxist revolutionary had helped to transform a wave of strikes and protests in the city into open revolution – the so-called Spartacist uprising. But by January 12, she was on the run, the revolt crushed by right-wing militia groups deployed by Germany’s new socialist government. And even if we could get a President Gillibrand in 2020, another lukewarm Democratic presidency will not only further impoverish and destabilize the working class and its suffering institutions, it will also all but guarantee that 2024 brings us POTUS Hamburglar in an SS uniform. No, it’s Bernie or bust. I don’t care if we have to roll him out on a hand truck and sprinkle cocaine into his coleslaw before every speech. If he dies mid-run, we’ll stuff him full of sawdust, shove a hand up his ass, and operate him like a goddamn muppet.

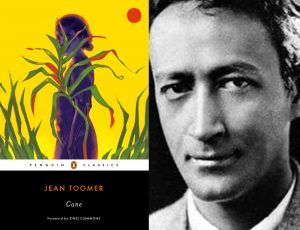

And even if we could get a President Gillibrand in 2020, another lukewarm Democratic presidency will not only further impoverish and destabilize the working class and its suffering institutions, it will also all but guarantee that 2024 brings us POTUS Hamburglar in an SS uniform. No, it’s Bernie or bust. I don’t care if we have to roll him out on a hand truck and sprinkle cocaine into his coleslaw before every speech. If he dies mid-run, we’ll stuff him full of sawdust, shove a hand up his ass, and operate him like a goddamn muppet. The literary world was then (as it is now, perhaps) hungry for representative black voices; as Hutchinson writes, “Many stressed the ‘authenticity’ of Toomer’s African-Americans and the lyrical voice with which he conjured them into being.” This act of conjuring lured critics into reflexively accepting the book as a representation of the black South—and Toomer as the voice of that South. As his one-time friend Waldo Frank remarked in a forward to the book’s original edition, “This book is the South.” Cane transformed Toomer into a Negro literary star whose influence would filter down through African-American literary history: his interest in the folk tradition crystallized the Harlem Renaissance’s search for a useable Negro past, and would be instructive for later writers from Zora Neale Hurston to Ralph Ellison to Elizabeth Alexander.

The literary world was then (as it is now, perhaps) hungry for representative black voices; as Hutchinson writes, “Many stressed the ‘authenticity’ of Toomer’s African-Americans and the lyrical voice with which he conjured them into being.” This act of conjuring lured critics into reflexively accepting the book as a representation of the black South—and Toomer as the voice of that South. As his one-time friend Waldo Frank remarked in a forward to the book’s original edition, “This book is the South.” Cane transformed Toomer into a Negro literary star whose influence would filter down through African-American literary history: his interest in the folk tradition crystallized the Harlem Renaissance’s search for a useable Negro past, and would be instructive for later writers from Zora Neale Hurston to Ralph Ellison to Elizabeth Alexander.