Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

A small shark spots its prey—a meaty, seemingly defenseless octopus. The shark ambushes, and then, in one of the most astonishing sequences in the series Blue Planet II, the octopus escapes. First, it shoves one of its arms into the predator’s vulnerable gills. Once released, it moves to protect itself—it grabs discarded seashells and swiftly arranges them into a defensive dome.

Thanks to acts like these, cephalopods—the group that includes octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish—have become renowned for their intelligence. Octopuses, for example, have been seen unscrewing jar lids to get at hidden food, carrying coconut shells to use as armor, barricading their den with stones, and squirting jets of water to deter predators or short out aquarium lights. But why did they become intelligent in the first place? Why did this one group of mollusks, among an otherwise slow and dim-witted dynasty of snails, slugs, clams, oysters, and mussels, evolve into creatures that are famed for their big brains? These are hard questions to answer, especially because cephalopods aren’t just weirdly intelligent; they’re also very weird for intelligent animals. Members of the animal kingdom’s intelligentsia tend to be sociable; indeed, the need to remember and manage a complex network of relationships might have helped drive the evolution of their brains. Smart animals also tend to be long-lived, since a large brain both takes a long time to grow and helps an animal avoid danger. Apes, elephants, whales and dolphins, crows and other corvids, parrots: They all share these traits.

Cephalopods do not. With rare exceptions, most of them are solitary animals that aren’t above cannibalizing one another when they meet. Even those that swim in groups, like some squid, don’t form the kinds of deep social bonds that chimps or dolphins do. Cephalopods also tend to live fast and die young. Most have life spans shorter than two years, and many die after their first bout of sex and reproduction. This combination of short lives, solitude, and smarts is unique to cephalopods. And according to a recent paper by Piero Amodio from the University of Cambridge and five of his colleagues, the traits are all linked to a particular development in the octopus’s evolutionary history: Its ancestors lost their shells.

More here.

“Anytime we take Tylenol because we have the flu and we feel terrible, that’s actually you playing with tolerance,” says Stanford University microbiologist

“Anytime we take Tylenol because we have the flu and we feel terrible, that’s actually you playing with tolerance,” says Stanford University microbiologist  On a spring night

On a spring night What does it mean to be a good person? To act ethically and morally in the world? In the old days we might appeal to the instructions we get from God, but a modern naturalist has to look elsewhere. Today I do a rare solo podcast, where I talk about my personal views on morality, a variety of “constructivism” according to which human beings construct their ethical stances starting from basic impulses, logical reasoning, and communicating with others.

What does it mean to be a good person? To act ethically and morally in the world? In the old days we might appeal to the instructions we get from God, but a modern naturalist has to look elsewhere. Today I do a rare solo podcast, where I talk about my personal views on morality, a variety of “constructivism” according to which human beings construct their ethical stances starting from basic impulses, logical reasoning, and communicating with others. Under the influence of mind-altering drugs, individuals cannot distinguish between subjective experience and external objects. Even after the ego returns and normal cognitive processes resume, people have an unshakable belief in what they encountered in their altered cognitive state. This isn’t to say that psychedelic-users are deluded. To the contrary, Pollan suggests, they may have been granted access to hidden truths. Pollan invokes Aldous Huxley’s notion of a “mind at large” and philosopher Henri Bergson’s theory of distributed consciousness to explain this phenomenon. Both thinkers purported that the human brain does not singularly produce consciousness; rather the brain enables humans to “tune in” to certain frequencies like someone turning the dial of a radio. For Huxley and Pollan, psychedelics increase the number of stations available.

Under the influence of mind-altering drugs, individuals cannot distinguish between subjective experience and external objects. Even after the ego returns and normal cognitive processes resume, people have an unshakable belief in what they encountered in their altered cognitive state. This isn’t to say that psychedelic-users are deluded. To the contrary, Pollan suggests, they may have been granted access to hidden truths. Pollan invokes Aldous Huxley’s notion of a “mind at large” and philosopher Henri Bergson’s theory of distributed consciousness to explain this phenomenon. Both thinkers purported that the human brain does not singularly produce consciousness; rather the brain enables humans to “tune in” to certain frequencies like someone turning the dial of a radio. For Huxley and Pollan, psychedelics increase the number of stations available. Rosenblatt’s effort to vindicate liberalism by demonstrating that it was never what critics on the right and left said it was in the first place results in a highly readable and engaging history of nineteenth-century French politics, but it’s not entirely convincing. The distinction Rosenblatt relies on between “liberality” as an individual virtue and “liberalism” as a set of government policies is blurred by precisely those seventeenth- and eighteenth-century thinkers most often held up as the first liberals, and whom Rosenblatt is determined to exclude from that category. On Rosenblatt’s own account, Locke understood toleration as a personal virtue, but he also required the state to defend it as a matter of policy. Nineteenth-century French liberalism may well have been a more self-conscious political movement, but, in Rosenblatt’s telling, it was not notably more coherent in its substance than eighteenth-century British Whiggism, and certainly not more politically effective than its nineteenth-century British counterpart, which operated within a stable constitutional order and consequently achieved much more in practice than the French model. French liberalism is undoubtedly philosophically significant and deeply intertwined with other European liberalisms, but Rosenblatt does not definitively show that the precedence we tend to give to the British as progenitors and exemplars of liberalism is misplaced.

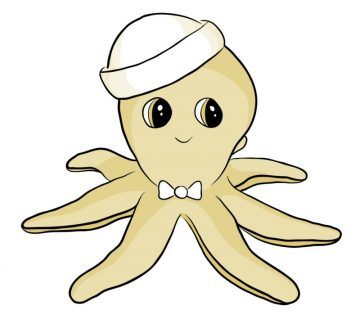

Rosenblatt’s effort to vindicate liberalism by demonstrating that it was never what critics on the right and left said it was in the first place results in a highly readable and engaging history of nineteenth-century French politics, but it’s not entirely convincing. The distinction Rosenblatt relies on between “liberality” as an individual virtue and “liberalism” as a set of government policies is blurred by precisely those seventeenth- and eighteenth-century thinkers most often held up as the first liberals, and whom Rosenblatt is determined to exclude from that category. On Rosenblatt’s own account, Locke understood toleration as a personal virtue, but he also required the state to defend it as a matter of policy. Nineteenth-century French liberalism may well have been a more self-conscious political movement, but, in Rosenblatt’s telling, it was not notably more coherent in its substance than eighteenth-century British Whiggism, and certainly not more politically effective than its nineteenth-century British counterpart, which operated within a stable constitutional order and consequently achieved much more in practice than the French model. French liberalism is undoubtedly philosophically significant and deeply intertwined with other European liberalisms, but Rosenblatt does not definitively show that the precedence we tend to give to the British as progenitors and exemplars of liberalism is misplaced. Its body is light blue and 100 percent synthetic. It’s a good-natured and naive octopus, and its smile is genuine. Its eyebrows are green, as are the two blushing spots on its cheeks. It weighs 11.4 ounces. It’s clearly intelligent—as nearly all octopuses are, of course. It wears a bow tie, and a sailor’s cap is cocked rakishly just a little to the left. If you squeeze the animal’s head (which is objectively small, but enormous compared to its body), a melody plays (Bach, I’m almost positive). Really, there are four melodies (all four by Bach, I think): to go from one to another, you just have to squeeze the creature’s head.

Its body is light blue and 100 percent synthetic. It’s a good-natured and naive octopus, and its smile is genuine. Its eyebrows are green, as are the two blushing spots on its cheeks. It weighs 11.4 ounces. It’s clearly intelligent—as nearly all octopuses are, of course. It wears a bow tie, and a sailor’s cap is cocked rakishly just a little to the left. If you squeeze the animal’s head (which is objectively small, but enormous compared to its body), a melody plays (Bach, I’m almost positive). Really, there are four melodies (all four by Bach, I think): to go from one to another, you just have to squeeze the creature’s head. Rudyard Kipling used to be a household name. Born in 1865 in Bombay, where his father taught at an arts school, and then exiled as a boy to England, he returned to India as a teen-ager, and quickly established himself as the great chronicler of the Anglo-Indian experience. He was Britain’s first Nobel laureate in literature, and probably the most widely read writer since Tennyson. People knew his poems by heart, read his stories to their children. The Queen wanted to knight him. But in recent years Kipling’s reputation has taken such a beating that it’s a wonder any sensible critic would want to go near him now. Kipling has been variously labelled a colonialist, a jingoist, a racist, an anti-Semite, a misogynist, a right-wing imperialist warmonger; and—though some scholars have argued that his views were more complicated than he is given credit for—to some degree he really was all those things. That he was also a prodigiously gifted writer who created works of inarguable greatness hardly matters anymore, at least not in many classrooms, where Kipling remains politically toxic.

Rudyard Kipling used to be a household name. Born in 1865 in Bombay, where his father taught at an arts school, and then exiled as a boy to England, he returned to India as a teen-ager, and quickly established himself as the great chronicler of the Anglo-Indian experience. He was Britain’s first Nobel laureate in literature, and probably the most widely read writer since Tennyson. People knew his poems by heart, read his stories to their children. The Queen wanted to knight him. But in recent years Kipling’s reputation has taken such a beating that it’s a wonder any sensible critic would want to go near him now. Kipling has been variously labelled a colonialist, a jingoist, a racist, an anti-Semite, a misogynist, a right-wing imperialist warmonger; and—though some scholars have argued that his views were more complicated than he is given credit for—to some degree he really was all those things. That he was also a prodigiously gifted writer who created works of inarguable greatness hardly matters anymore, at least not in many classrooms, where Kipling remains politically toxic. At three o’clock in the afternoon on September 4, 1882, the electrical age began. The Edison Illuminating Company switched on its Pearl Street power plant, and a network of copper wires came alive, delivering current to a few dozen buildings in the surrounding neighborhood. One of those buildings housed this newspaper. As night fell, reporters at The New York Times gloried in the steady illumination thrown off by Thomas Edison’s electric lamps. “The light was soft, mellow, and grateful to the eye, and it seemed almost like writing by daylight,”

At three o’clock in the afternoon on September 4, 1882, the electrical age began. The Edison Illuminating Company switched on its Pearl Street power plant, and a network of copper wires came alive, delivering current to a few dozen buildings in the surrounding neighborhood. One of those buildings housed this newspaper. As night fell, reporters at The New York Times gloried in the steady illumination thrown off by Thomas Edison’s electric lamps. “The light was soft, mellow, and grateful to the eye, and it seemed almost like writing by daylight,”  A diverting Beltway pastime during the heyday of the Washington Consensus was to gently mock Joseph E. Stiglitz. It was remarkably easy for pundits to wave away his prestigious awards (Nobel Prize in Economics) and positions (World Bank chief economist, chairman of Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers) and dismiss his warnings about “market fundamentalism” as overripe hyperbole. In 2004

A diverting Beltway pastime during the heyday of the Washington Consensus was to gently mock Joseph E. Stiglitz. It was remarkably easy for pundits to wave away his prestigious awards (Nobel Prize in Economics) and positions (World Bank chief economist, chairman of Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers) and dismiss his warnings about “market fundamentalism” as overripe hyperbole. In 2004  When

When  The US military’s carbon bootprint is enormous. Like corporate supply chains, it relies upon an extensive global network of container ships, trucks and cargo planes to supply its operations with everything from bombs to humanitarian aid and hydrocarbon fuels. Our

The US military’s carbon bootprint is enormous. Like corporate supply chains, it relies upon an extensive global network of container ships, trucks and cargo planes to supply its operations with everything from bombs to humanitarian aid and hydrocarbon fuels. Our  There is something very moving about the conversation between these young women, a sense of generational rise that, as we know from every precedent from the Renaissance onwards, has the power to ignite movements and change history.

There is something very moving about the conversation between these young women, a sense of generational rise that, as we know from every precedent from the Renaissance onwards, has the power to ignite movements and change history. The popularity of video games is staggering. Last year, the top 25 public game companies—China’s Tencent, Sony, and Microsoft ranking highest—had annual earnings of more than $100 billion for the first time.1 The United States video game industry earned more than global box office movie ticket sales, U.S. video streaming subscriptions, and the U.S. music industry.2 By 2021, according to Statista, a market research firm, 2.7 billion people will be playing video games, up from 1.8 billion five years ago. A Pew survey reveals the age group that plays most often is 18 to 29.3In the 30 to 49 age group, nearly 50 percent of men and 40 percent of women play. A study in Europe shows people 45 and up are more likely to play video games than children aged 6 to 14.

The popularity of video games is staggering. Last year, the top 25 public game companies—China’s Tencent, Sony, and Microsoft ranking highest—had annual earnings of more than $100 billion for the first time.1 The United States video game industry earned more than global box office movie ticket sales, U.S. video streaming subscriptions, and the U.S. music industry.2 By 2021, according to Statista, a market research firm, 2.7 billion people will be playing video games, up from 1.8 billion five years ago. A Pew survey reveals the age group that plays most often is 18 to 29.3In the 30 to 49 age group, nearly 50 percent of men and 40 percent of women play. A study in Europe shows people 45 and up are more likely to play video games than children aged 6 to 14.