Eimear McBride in The Guardian:

Within the first few pages of Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights the narrator writes of her fondly remembered, now long-deceased mother: “I never knew a person so indifferent to the past. It was as if she did not know who she was.” It’s an unsentimental, matter-of-fact kind of assessment of a life that, having failed to be the occasion of much self-examination in its possessor, is now dwindling unhindered into a soon-to-be-forgotten past. Hardwick’s narrator – and fellow Elizabeth – doesn’t fault her mother for this dimly lit sense of self or lack of strongly asserted identity. Rather, in much the same way that she and her many siblings respond to their mother’s prodigious childbearing by offering up a singularly low birth rate of their own, she simply adopts a fundamentally different approach.

Within the first few pages of Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights the narrator writes of her fondly remembered, now long-deceased mother: “I never knew a person so indifferent to the past. It was as if she did not know who she was.” It’s an unsentimental, matter-of-fact kind of assessment of a life that, having failed to be the occasion of much self-examination in its possessor, is now dwindling unhindered into a soon-to-be-forgotten past. Hardwick’s narrator – and fellow Elizabeth – doesn’t fault her mother for this dimly lit sense of self or lack of strongly asserted identity. Rather, in much the same way that she and her many siblings respond to their mother’s prodigious childbearing by offering up a singularly low birth rate of their own, she simply adopts a fundamentally different approach.

Sleepless Nights – first published in 1979 when its author was 63, renowned and respected as one of the pre-eminent writers in her field – stands in polar opposition to this maternal model of the deserted self and, most particularly, of the deserted female self. There is no confusion of selfhood or incoherence of purpose. This is a narrator who knows who she is and, pretty much, how she got to be that way. The resultant restive narrative is a deep delve into the processes of her thinking as she sleeplessly rolls back and forth across ideas, memories and conclusions. For the reader it is this encounter with a formidable mind working hard, mapping the journey from its root consciousness through myriad perceptions and recollections out into the physical world – where it may, or may not, allow itself to be changed by what it finds – which forms the spine of pleasure that holds the fragmented narrative together.

More here. (Note: One of my all-time favorite books!)

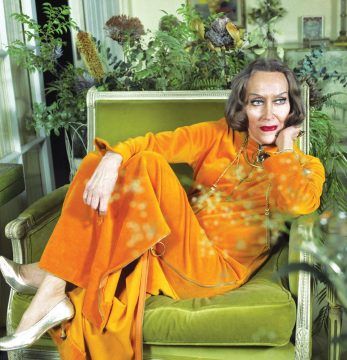

One evening in early 1950, the film mogul Louis B. Mayer hosted a small dinner party for the actress Gloria Swanson. She was fifty-one years old, which was not considered an ancient, crone-like age, even in an industry that values youth above all else. Still, she was in need of a professional boost. Mayer’s small soiree was something of a ceremonial gesture. Here was one of the last tycoons of classic Hollywood extending his hand and his hospitality to an actress who was tottering, on marabou-covered heels, back into the business after a decade-long fermata.

One evening in early 1950, the film mogul Louis B. Mayer hosted a small dinner party for the actress Gloria Swanson. She was fifty-one years old, which was not considered an ancient, crone-like age, even in an industry that values youth above all else. Still, she was in need of a professional boost. Mayer’s small soiree was something of a ceremonial gesture. Here was one of the last tycoons of classic Hollywood extending his hand and his hospitality to an actress who was tottering, on marabou-covered heels, back into the business after a decade-long fermata. The gospels (which show knowledge of the fall of the Jerusalem Temple in AD70) were written at least two decades after Paul’s epistles. And the Gospel of John was possibly written as late as the second century. It presents a Jesus who talks a great deal about his own status as God’s son. This more likely reflects the beliefs of a later era than that of Jesus himself, and John’s gospel may indeed be a biography of Christ written to suit the interests and beliefs of John’s own particular branch of Christianity. The episode of the woman taken in adultery – “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her” – which appears only in this gospel, is not found in the earliest manuscripts, and is likely to be an even later addition.

The gospels (which show knowledge of the fall of the Jerusalem Temple in AD70) were written at least two decades after Paul’s epistles. And the Gospel of John was possibly written as late as the second century. It presents a Jesus who talks a great deal about his own status as God’s son. This more likely reflects the beliefs of a later era than that of Jesus himself, and John’s gospel may indeed be a biography of Christ written to suit the interests and beliefs of John’s own particular branch of Christianity. The episode of the woman taken in adultery – “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her” – which appears only in this gospel, is not found in the earliest manuscripts, and is likely to be an even later addition. Suppose you were to mash up three of the greatest of all children’s fantasies: J.M. Barrie’s

Suppose you were to mash up three of the greatest of all children’s fantasies: J.M. Barrie’s  Evgeny Morozov in The New Left Review:

Evgeny Morozov in The New Left Review: Andy West interview with Victoria Brooks in 3:AM Magazine:

Andy West interview with Victoria Brooks in 3:AM Magazine: Felicia Wong in the Boston Review:

Felicia Wong in the Boston Review: Thomas Meaney in The New Statesman:

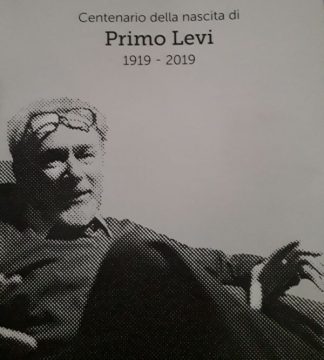

Thomas Meaney in The New Statesman: These words anchor the exhibition Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away. The quote above is the first line visitors read when they enter the gallery. Levi establishes a moral framework, an emotional gravity that drives the visitor experience. In my own time within the exhibition, it felt as though this line from Levi echoed throughout the entirety of my visit. Born in 1919—one hundred years ago—in Turin, Italy, Levi worked as a chemist before his arrest and deportation to Auschwitz in 1943. He survived Auschwitz and, in 1947, published an account of his experiences. Translated into nearly 40 languages, If This Is a Man (also known as Survival in Auschwitz) endures today.

These words anchor the exhibition Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away. The quote above is the first line visitors read when they enter the gallery. Levi establishes a moral framework, an emotional gravity that drives the visitor experience. In my own time within the exhibition, it felt as though this line from Levi echoed throughout the entirety of my visit. Born in 1919—one hundred years ago—in Turin, Italy, Levi worked as a chemist before his arrest and deportation to Auschwitz in 1943. He survived Auschwitz and, in 1947, published an account of his experiences. Translated into nearly 40 languages, If This Is a Man (also known as Survival in Auschwitz) endures today. We are shackled to the pangs and shocks of life, wrote Virginia Woolf in The Waves (1931), ‘as bodies to wild horses’. Or are we? Serge Faguet, a Russian-born tech entrepreneur and self-declared ‘extreme biohacker’, believes otherwise. He wants to tame the bucking steed of his own biochemistry via an elixir of drugs, implants, medical monitoring and behavioural ‘hacks’ that optimise his own biochemistry. In his personal quest to become one of the ‘immortal posthuman gods that cast off the limits of our biology, and spread across the Universe’, Faguet claims to have spent upwards of $250,000 so far – including hiring ‘fashion models to have sex with in order to save time on dating and focus on other priorities’.

We are shackled to the pangs and shocks of life, wrote Virginia Woolf in The Waves (1931), ‘as bodies to wild horses’. Or are we? Serge Faguet, a Russian-born tech entrepreneur and self-declared ‘extreme biohacker’, believes otherwise. He wants to tame the bucking steed of his own biochemistry via an elixir of drugs, implants, medical monitoring and behavioural ‘hacks’ that optimise his own biochemistry. In his personal quest to become one of the ‘immortal posthuman gods that cast off the limits of our biology, and spread across the Universe’, Faguet claims to have spent upwards of $250,000 so far – including hiring ‘fashion models to have sex with in order to save time on dating and focus on other priorities’. The Pakistani media is now enduring its darkest phase yet. Major General Asif Ghafoor, the head of the Pakistan Army’s public relations department, has been circulating the online profiles of journalists he judges to be involved in antistate activities. In a press conference last December, he issued a heartfelt plea: if journalists filed positive stories for just six months, Pakistan would become a great nation. Mostly, Pakistani journalists obliged. Writers who were once bold and boisterous, taking on military dictators and civilian rulers and extremist organizations, have now become patriotic—or have found themselves out of work. Without jobs, some of the country’s top columnists and prime-time TV journalists are learning to start their own YouTube channels. Others receive threats from anonymous entities claiming to represent the state intelligence services.

The Pakistani media is now enduring its darkest phase yet. Major General Asif Ghafoor, the head of the Pakistan Army’s public relations department, has been circulating the online profiles of journalists he judges to be involved in antistate activities. In a press conference last December, he issued a heartfelt plea: if journalists filed positive stories for just six months, Pakistan would become a great nation. Mostly, Pakistani journalists obliged. Writers who were once bold and boisterous, taking on military dictators and civilian rulers and extremist organizations, have now become patriotic—or have found themselves out of work. Without jobs, some of the country’s top columnists and prime-time TV journalists are learning to start their own YouTube channels. Others receive threats from anonymous entities claiming to represent the state intelligence services. Quantum computers, which use light particles (photons) instead of electrons to transmit and process data, hold the promise of a new era of research in which the time needed to realize lifesaving drugs and new technologies will be significantly shortened. Photons are promising candidates for quantum computation because they can propagate across long distances without losing information, but when they are stored in matter they become fragile and susceptible to decoherence. Now researchers with the Photonics Initiative at the Advanced Science Research Center (ASRC) at The Graduate Center, CUNY have developed a new protocol for storing and releasing a single photon in an embedded eigenstate—a quantum state that is virtually unaffected by loss and decoherence. The novel protocol, detailed in the current issue of Optica, aims to advance the development of quantum computers.

Quantum computers, which use light particles (photons) instead of electrons to transmit and process data, hold the promise of a new era of research in which the time needed to realize lifesaving drugs and new technologies will be significantly shortened. Photons are promising candidates for quantum computation because they can propagate across long distances without losing information, but when they are stored in matter they become fragile and susceptible to decoherence. Now researchers with the Photonics Initiative at the Advanced Science Research Center (ASRC) at The Graduate Center, CUNY have developed a new protocol for storing and releasing a single photon in an embedded eigenstate—a quantum state that is virtually unaffected by loss and decoherence. The novel protocol, detailed in the current issue of Optica, aims to advance the development of quantum computers. The world is increasingly at risk of “climate apartheid”, where the rich pay to escape heat and hunger caused by the escalating climate crisis while the rest of the world suffers, a report from a UN human rights expert has said.

The world is increasingly at risk of “climate apartheid”, where the rich pay to escape heat and hunger caused by the escalating climate crisis while the rest of the world suffers, a report from a UN human rights expert has said. Placed together, the book’s two longest chapters, “Big Bad Science” and “The Medical Misinformation Mess”, lay out the charge sheet against modern scientific research in medicine. Medical research, particularly “Big Science” or “Big Data”, has always promised far more than it has delivered, and Big Science has in fact contributed little to medical advances; research and clinical trials, meanwhile, are in the midst of a “replication crisis”, where a huge percentage of trials either never are or cannot be replicated. The first issue medical research must face if it is to reform is “that the culture of contemporary medical research is so conformist that truly original thinkers can no longer prosper in such an environment, and that science selects for perseverance and sociability at the expense of intelligence and creativity”. O’Mahony quotes Bruce Charlton: “[the requirements of contemporary research are] enough to deter almost anyone with a spark of vitality or self-respect … Modern science is just too dull an activity to attract, retain or promote many of the most intelligent and creative people”. “Real scientists,” says O’Mahony, “tend to be reticent, self-effacing, publicity-shy and full of doubt and uncertainty, unlike the gurning hucksters who seem to infest medical research.”

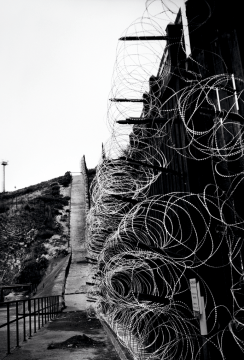

Placed together, the book’s two longest chapters, “Big Bad Science” and “The Medical Misinformation Mess”, lay out the charge sheet against modern scientific research in medicine. Medical research, particularly “Big Science” or “Big Data”, has always promised far more than it has delivered, and Big Science has in fact contributed little to medical advances; research and clinical trials, meanwhile, are in the midst of a “replication crisis”, where a huge percentage of trials either never are or cannot be replicated. The first issue medical research must face if it is to reform is “that the culture of contemporary medical research is so conformist that truly original thinkers can no longer prosper in such an environment, and that science selects for perseverance and sociability at the expense of intelligence and creativity”. O’Mahony quotes Bruce Charlton: “[the requirements of contemporary research are] enough to deter almost anyone with a spark of vitality or self-respect … Modern science is just too dull an activity to attract, retain or promote many of the most intelligent and creative people”. “Real scientists,” says O’Mahony, “tend to be reticent, self-effacing, publicity-shy and full of doubt and uncertainty, unlike the gurning hucksters who seem to infest medical research.” Let us now meet the migrants themselves. We begin with one quietly cheerful shelter for asylum seekers. Although the Methodists had started it, “We have Unitarians, we have Catholics, we have Presbyterians, Lutherans, and some people who are atheists. I even have a couple of Republicans helping out! They talk to me about the wall but are still here helping out.” In keeping with the regional mood, I was asked not to identify the place (“in the Tucson foothills”), and the co-coordinator who showed me around (she was called Diane) declined to provide her last name, because “we’re just kinda protecting our folks. We don’t want location or names or anything like that, because I worry about protesters.” No location, then, but I will say that planted in the gravel in front of the building stood a sign from that brave organization No More Deaths: humanitarian aid is never a crime—drop the charges, with a hand reaching up for a water jug somewhere between two saguaro cacti.

Let us now meet the migrants themselves. We begin with one quietly cheerful shelter for asylum seekers. Although the Methodists had started it, “We have Unitarians, we have Catholics, we have Presbyterians, Lutherans, and some people who are atheists. I even have a couple of Republicans helping out! They talk to me about the wall but are still here helping out.” In keeping with the regional mood, I was asked not to identify the place (“in the Tucson foothills”), and the co-coordinator who showed me around (she was called Diane) declined to provide her last name, because “we’re just kinda protecting our folks. We don’t want location or names or anything like that, because I worry about protesters.” No location, then, but I will say that planted in the gravel in front of the building stood a sign from that brave organization No More Deaths: humanitarian aid is never a crime—drop the charges, with a hand reaching up for a water jug somewhere between two saguaro cacti. Caradec’s Dictionary, newly translated into English by Chris Clarke, lists some 850 gestures that “successively address each part of the body, from top to bottom, from scalp to toe by way of the upper limbs”, and may be used as well as or instead of speech. They are numbered and ordered in a taxonomy running from 1.01 (“to nod one’s head vertically up and down, back to front, one or several times: acquiescence”) to 37.12 (“to kick an adversary in the rear end: aggression”), and accompanied by Philippe Cousin’s illustrations. The majority of them are what the psychologist David McNeill has called “imagistic”, by which parts of the body are arranged to figure an imagined object or action (such as blowing a kiss, or proffering one’s middle finger), and are “effected voluntarily by humankind in order to communicate with each other”. The emphasis designates this type of non-verbal expression – Adam Kendon calls it “visible action as utterance” in his seminal Gesture (2004) – as a sub-category of body language more broadly, which comprises both conscious (that is, learnt) and unconscious (instinctive) movements.

Caradec’s Dictionary, newly translated into English by Chris Clarke, lists some 850 gestures that “successively address each part of the body, from top to bottom, from scalp to toe by way of the upper limbs”, and may be used as well as or instead of speech. They are numbered and ordered in a taxonomy running from 1.01 (“to nod one’s head vertically up and down, back to front, one or several times: acquiescence”) to 37.12 (“to kick an adversary in the rear end: aggression”), and accompanied by Philippe Cousin’s illustrations. The majority of them are what the psychologist David McNeill has called “imagistic”, by which parts of the body are arranged to figure an imagined object or action (such as blowing a kiss, or proffering one’s middle finger), and are “effected voluntarily by humankind in order to communicate with each other”. The emphasis designates this type of non-verbal expression – Adam Kendon calls it “visible action as utterance” in his seminal Gesture (2004) – as a sub-category of body language more broadly, which comprises both conscious (that is, learnt) and unconscious (instinctive) movements. Sameer Rahim’s debut novel is a tender, pin-sharp portrait of a marriage and a community. It is a wonderful achievement; an invigorating reminder of the power fiction has to challenge lazy stereotypes, and stretch the reader’s heart. Asghar Dhalani and Zahra Amir are young west Londoners, from a tight-knit but fractious east African Muslim community. They have known each other since childhood, but their families have very different approaches to the challenge of making a life in England. The Amirs pride themselves on their refinement and open-mindedness – Zahra left home to study at Cambridge, and is fond of saying things like, “it’s textbook Orientalism, Mummy”. The Dhalanis are “the most traditional of the traditional”; 19-year-old Asghar won’t eat a cheese sandwich until he’s checked it’s halal. Everyone, not least Asghar, is surprised when Zahra accepts his proposal.

Sameer Rahim’s debut novel is a tender, pin-sharp portrait of a marriage and a community. It is a wonderful achievement; an invigorating reminder of the power fiction has to challenge lazy stereotypes, and stretch the reader’s heart. Asghar Dhalani and Zahra Amir are young west Londoners, from a tight-knit but fractious east African Muslim community. They have known each other since childhood, but their families have very different approaches to the challenge of making a life in England. The Amirs pride themselves on their refinement and open-mindedness – Zahra left home to study at Cambridge, and is fond of saying things like, “it’s textbook Orientalism, Mummy”. The Dhalanis are “the most traditional of the traditional”; 19-year-old Asghar won’t eat a cheese sandwich until he’s checked it’s halal. Everyone, not least Asghar, is surprised when Zahra accepts his proposal.