You Don’t Look Like Someone

i am a stranger here

they have put me up in the fancy neighborhood and

when the alabaster white-haired fur coat woman

and her hesitant eyes hold the elevator for me and say

you don’t look like someone who i’ve met before

centuries pass between the someone and the who

and my muscles tense as i arm myself

with explanations for my presence in the building,

this learned response, survival staple

gray matter imprinted infographic:

“how to keep a white woman from panicking”

i am a guest artist

i’m only temporary

i leave in December

i explain myself (away):

i am not a threat i am not a threat

i am not a threat i am not a threat and

i wonder what else might’ve been

in the canyon between the someone and the who

you don’t look like someone

who belongs here

you don’t look like someone

who inherited all the world

you don’t look like someone

who can pay these property taxes

really you look like the doorwoman

maybe you are her daughter, and forgot?

just a moment ago, our president was black but

you look like the doorwoman and

you don’t look like someone

and there was a moment when, instead of explain, i might have flipped my extensions and YES GIRL i just moved in and girl don’t you know i love it here! i’m never gonna leave, honey BELIEVE THAT! All clean and fancy up in here! where you get a coat like that? i want me a coat like that! girl, we finna TURN UP in this bitch! i’m finna tell my cousin ’bout this place. mmhmm, we movin right on up, you betta look at god ’cause won’t he do it. y’all got some thin walls in this place tho. ’spensive as hell but y’all got some thin walls. you like Biggie? but isn’t the ride always over before you even know what happened?

you don’t look like someone

who

i’ve met before

and only later do i realize—

i could’ve

said the same to her

by McKenzie Chinn

from Rattle #62, Winter 2018

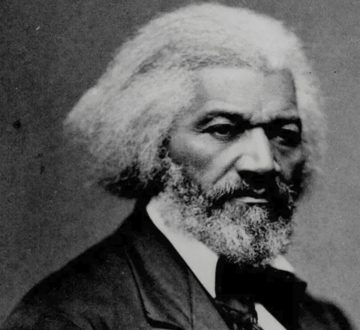

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day?

I am not included within the pale of this glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day? A few years ago the melody for this song came to me in a dream. I woke up from a nap, and as I took a stroll down a California beach, the song structure began to assemble itself. I was there to see a lover for the last time and say goodbye. But in that dream I had decided to move there instead, close to the ocean, abandoning my plans to attend graduate school in Islamic studies, back on the East Coast. In those days, I was consumed by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s recordings. Melodies often dance across my dreams, and back then, each was steeped in the heat and hue of his music.

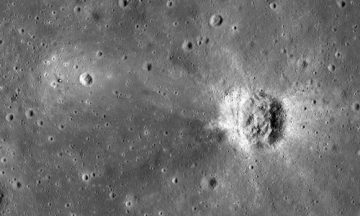

A few years ago the melody for this song came to me in a dream. I woke up from a nap, and as I took a stroll down a California beach, the song structure began to assemble itself. I was there to see a lover for the last time and say goodbye. But in that dream I had decided to move there instead, close to the ocean, abandoning my plans to attend graduate school in Islamic studies, back on the East Coast. In those days, I was consumed by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s recordings. Melodies often dance across my dreams, and back then, each was steeped in the heat and hue of his music. On 20 July 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin landed on the Moon while Michael Collins orbited in the command module Columbia. “Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed” became one of the most iconic statements of the Apollo experience and set the stage for five additional Apollo landings.

On 20 July 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin landed on the Moon while Michael Collins orbited in the command module Columbia. “Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed” became one of the most iconic statements of the Apollo experience and set the stage for five additional Apollo landings. I once had a friend named Alice who suddenly decided to attain optimum physical fitness. She committed to a strict regime and almost instantly achieved extraordinary results.The trouble was that she spent so much time exercising that she neglected her friendships, abandoned her hobbies, and forfeited all occasions for socialising. She pursued health at the expense of everything else she valued.

I once had a friend named Alice who suddenly decided to attain optimum physical fitness. She committed to a strict regime and almost instantly achieved extraordinary results.The trouble was that she spent so much time exercising that she neglected her friendships, abandoned her hobbies, and forfeited all occasions for socialising. She pursued health at the expense of everything else she valued. A Forest Service report published last year found that across the U.S., populated areas lost about 175,000 acres of trees per year between 2009 and 2014, or approximately 36 million trees per year. Forty-five states had a net decline in tree cover in these areas, with 23 of those states experiencing significant decreases. Meanwhile, urban regions showed a particular decline, along with an increase in what the researchers call “impervious surfaces” – in other words, concrete.

A Forest Service report published last year found that across the U.S., populated areas lost about 175,000 acres of trees per year between 2009 and 2014, or approximately 36 million trees per year. Forty-five states had a net decline in tree cover in these areas, with 23 of those states experiencing significant decreases. Meanwhile, urban regions showed a particular decline, along with an increase in what the researchers call “impervious surfaces” – in other words, concrete. The inhabitants of Westeros and Essos repeatedly face versions of a classic moral dilemma: When is it morally permissible to cause harm in order to prevent further suffering? Philosophers have debated moral dilemmas like this for over a thousand years. “Utilitarian” theories say that all that matters for morality is maximizing good consequences for everyone overall, while “deontological” theories say that some actions are just wrong, even if they have good consequences. The tension between deontological and utilitarian ethics can be seen in the origin story of Jaime Lannister’s sobriquet “Kingslayer”: When the “Mad King” Aerys Targaryen orders for the entire city to be burned, massacring the many thousands of citizens that live there, Jaime violates his sacred oath to protect and serve his lord and instead slits the king’s throat. Utilitarian theories would praise Jaime’s decision to kill the Mad King, because it saves many thousands of lives, while deontological theories would prohibit killing one to save many others.

The inhabitants of Westeros and Essos repeatedly face versions of a classic moral dilemma: When is it morally permissible to cause harm in order to prevent further suffering? Philosophers have debated moral dilemmas like this for over a thousand years. “Utilitarian” theories say that all that matters for morality is maximizing good consequences for everyone overall, while “deontological” theories say that some actions are just wrong, even if they have good consequences. The tension between deontological and utilitarian ethics can be seen in the origin story of Jaime Lannister’s sobriquet “Kingslayer”: When the “Mad King” Aerys Targaryen orders for the entire city to be burned, massacring the many thousands of citizens that live there, Jaime violates his sacred oath to protect and serve his lord and instead slits the king’s throat. Utilitarian theories would praise Jaime’s decision to kill the Mad King, because it saves many thousands of lives, while deontological theories would prohibit killing one to save many others.

Now the raucousness begins in earnest, as Ives renders the Independence Day parade—a drunken, lurching revel with horses on the loose and church bells clanging and a fife-and-drum corps playing intentionally off-key (recalling those lusty if decidedly amateurish New England bands Ives knew so well from his youth). There are quotations galore, some 15 of them, from such popular tunes as “Battle Cry of Freedom,” “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “Yankee Doodle,” “Reveille,” “Marching Through Georgia,” and “Dixie,” in addition to “Columbia, Gem of the Ocean,” which the trombones deliver with gusto, though many of the tunes are distorted, distended, or truncated. All of these fragments furiously collide with each other, creating an exhilarating swirl, a feeling of polyrhythmic, harmonic chaos. The underlying philosophy here is a democratic ideal, that everything has its place in a piece of music: high art and low, consonance and dissonance, simplicity and mind-boggling complexity—everything goes. So complicated is the score that a second conductor is needed (in some performances, even a third). And in truth, Ives himself never knew if he’d ever hear this work performed. As he later wrote, “I remember distinctly, when I was scoring this, that there was a feeling of freedom as a boy has, on the Fourth of July, who wants to do anything he wants to do. … And I wrote this, feeling free to remember local things, etc, and to put [in] as many feelings and rhythms as I wanted to put together. And I did what I wanted to, quite sure that the thing would never be played, and perhaps could never be played.”

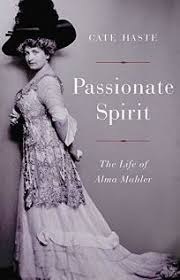

Now the raucousness begins in earnest, as Ives renders the Independence Day parade—a drunken, lurching revel with horses on the loose and church bells clanging and a fife-and-drum corps playing intentionally off-key (recalling those lusty if decidedly amateurish New England bands Ives knew so well from his youth). There are quotations galore, some 15 of them, from such popular tunes as “Battle Cry of Freedom,” “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “Yankee Doodle,” “Reveille,” “Marching Through Georgia,” and “Dixie,” in addition to “Columbia, Gem of the Ocean,” which the trombones deliver with gusto, though many of the tunes are distorted, distended, or truncated. All of these fragments furiously collide with each other, creating an exhilarating swirl, a feeling of polyrhythmic, harmonic chaos. The underlying philosophy here is a democratic ideal, that everything has its place in a piece of music: high art and low, consonance and dissonance, simplicity and mind-boggling complexity—everything goes. So complicated is the score that a second conductor is needed (in some performances, even a third). And in truth, Ives himself never knew if he’d ever hear this work performed. As he later wrote, “I remember distinctly, when I was scoring this, that there was a feeling of freedom as a boy has, on the Fourth of July, who wants to do anything he wants to do. … And I wrote this, feeling free to remember local things, etc, and to put [in] as many feelings and rhythms as I wanted to put together. And I did what I wanted to, quite sure that the thing would never be played, and perhaps could never be played.” The Gustav Mahler industry, in particular, is vicious in its representation of Alma as a self-serving narcissist who exaggerated her own role in the life of the great man, massaged the facts and was even, on account of her affair with Gropius, responsible for his death at the age of fifty. She was, the legend goes, an artistic gold-digger in whose eyes a man’s sexual attractiveness increased in proportion to his artistic ‘greatness’. But in this, as in so many other matters, Alma didn’t help: during a three-year affair with Oskar Kokoschka, which became darker and stranger as time went on, she told him that she would marry him only when he had created a masterpiece (she never did). And why at the end of her life, after marrying three well-known artists, did she revert to the name of the first? Was it because she reckoned that Mahler was the most important, the ‘greatest’ of the three?

The Gustav Mahler industry, in particular, is vicious in its representation of Alma as a self-serving narcissist who exaggerated her own role in the life of the great man, massaged the facts and was even, on account of her affair with Gropius, responsible for his death at the age of fifty. She was, the legend goes, an artistic gold-digger in whose eyes a man’s sexual attractiveness increased in proportion to his artistic ‘greatness’. But in this, as in so many other matters, Alma didn’t help: during a three-year affair with Oskar Kokoschka, which became darker and stranger as time went on, she told him that she would marry him only when he had created a masterpiece (she never did). And why at the end of her life, after marrying three well-known artists, did she revert to the name of the first? Was it because she reckoned that Mahler was the most important, the ‘greatest’ of the three?

The flashier fruits of Albert Einstein’s century-old insights are by now deeply embedded in the popular imagination: Black holes, time warps and wormholes show up regularly as plot points in movies, books, TV shows. At the same time, they fuel cutting-edge research, helping physicists pose questions about the nature of space, time, even information itself.

The flashier fruits of Albert Einstein’s century-old insights are by now deeply embedded in the popular imagination: Black holes, time warps and wormholes show up regularly as plot points in movies, books, TV shows. At the same time, they fuel cutting-edge research, helping physicists pose questions about the nature of space, time, even information itself.

Odessa is a young city by European standards, but what it lacks in historical gravitas it makes up for with its splendid architectural bones and worldliness. Cosmopolitan from its inception, its life began when Neapolitan officer General Don Jose de Ribas seized a Tatar-built fort, Hadji Bey, from the Turks in 1789. His conquest complete, de Ribas asked Catherine the Great if she liked the Grecian name Odessos. She did, but only once she’d feminized it to “Odessa.”

Odessa is a young city by European standards, but what it lacks in historical gravitas it makes up for with its splendid architectural bones and worldliness. Cosmopolitan from its inception, its life began when Neapolitan officer General Don Jose de Ribas seized a Tatar-built fort, Hadji Bey, from the Turks in 1789. His conquest complete, de Ribas asked Catherine the Great if she liked the Grecian name Odessos. She did, but only once she’d feminized it to “Odessa.” This problem is particularly acute in our modern consumer economy, in which political institutions, the economic system, and popular culture are all now primarily dedicated to the pursuit of happiness. This has had the perverse effect of creating a world of frustration and disappointment in which so many discover that happiness is beyond their grasp. The economy fails to deliver for the majority but urges everyone to spend beyond their means. We engage in “retail therapy,” spending for the momentary gratification of acquisition. We encounter advertisements that wrap themselves around us like a blizzard of snow, each promising that if we spend, and go on spending, we will be rewarded with endless delights. This spending helps drive climate change, which threatens to make the planet uninhabitable. Moreover, our sense of who we are seems to be increasingly detached from reality; we live out fantasy versions of ourselves, playing our own private form of air guitar. To constantly pursue something you can never catch is a form of madness. We have built this madness into the very structure of our lives. Every society in the world aims at economic growth, and every society encourages the endless accumulation of wealth. When it comes to wealth, we have great difficulty in saying enough is enough, because it is hard to know when we can safely say we have enough to face down every possible catastrophe.

This problem is particularly acute in our modern consumer economy, in which political institutions, the economic system, and popular culture are all now primarily dedicated to the pursuit of happiness. This has had the perverse effect of creating a world of frustration and disappointment in which so many discover that happiness is beyond their grasp. The economy fails to deliver for the majority but urges everyone to spend beyond their means. We engage in “retail therapy,” spending for the momentary gratification of acquisition. We encounter advertisements that wrap themselves around us like a blizzard of snow, each promising that if we spend, and go on spending, we will be rewarded with endless delights. This spending helps drive climate change, which threatens to make the planet uninhabitable. Moreover, our sense of who we are seems to be increasingly detached from reality; we live out fantasy versions of ourselves, playing our own private form of air guitar. To constantly pursue something you can never catch is a form of madness. We have built this madness into the very structure of our lives. Every society in the world aims at economic growth, and every society encourages the endless accumulation of wealth. When it comes to wealth, we have great difficulty in saying enough is enough, because it is hard to know when we can safely say we have enough to face down every possible catastrophe. At the end of the nineteenth century, Lafcadio Hearn was one of America’s best-known writers, one of a stellar company that included Mark Twain, Edgar Allan Poe, and Robert Louis Stevenson. Twain, Poe, and Stevenson have entered the established literary canon and are still read for duty and pleasure. Lafcadio Hearn has been forgotten, with two remarkable exceptions: in Louisiana and in Japan. Yet Hearn’s place in the canon is significant for many reasons, not least of which is how the twentieth century came to view the nineteenth. This view, both academic and popular, reflects the triumph of a certain futuristic Modernism over the mysteries of religion, folklore, and what was once called “folk wisdom.” To witness this phenomenon in time-lapse, sped-up motion, one need only consider Lafcadio Hearn, the Greek-born, Irish-raised, New World immigrant who metamorphosed from a celebrated fin-de-siècle American writer into the beloved Japanese cultural icon Koizumi Yakumo in less than a decade, in roughly the same time that Japan changed from a millennia-old feudal society into a great industrial power.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Lafcadio Hearn was one of America’s best-known writers, one of a stellar company that included Mark Twain, Edgar Allan Poe, and Robert Louis Stevenson. Twain, Poe, and Stevenson have entered the established literary canon and are still read for duty and pleasure. Lafcadio Hearn has been forgotten, with two remarkable exceptions: in Louisiana and in Japan. Yet Hearn’s place in the canon is significant for many reasons, not least of which is how the twentieth century came to view the nineteenth. This view, both academic and popular, reflects the triumph of a certain futuristic Modernism over the mysteries of religion, folklore, and what was once called “folk wisdom.” To witness this phenomenon in time-lapse, sped-up motion, one need only consider Lafcadio Hearn, the Greek-born, Irish-raised, New World immigrant who metamorphosed from a celebrated fin-de-siècle American writer into the beloved Japanese cultural icon Koizumi Yakumo in less than a decade, in roughly the same time that Japan changed from a millennia-old feudal society into a great industrial power.