Matthew Shaer in The New York Times:

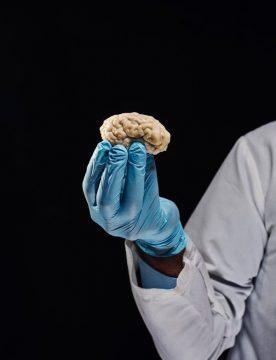

A few years ago, a scientist named Nenad Sestan began throwing around an idea for an experiment so obviously insane, so “wild” and “totally out there,” as he put it to me recently, that at first he told almost no one about it: not his wife or kids, not his bosses in Yale’s neuroscience department, not the dean of the university’s medical school. Like everything Sestan studies, the idea centered on the mammalian brain. More specific, it centered on the tree-shaped neurons that govern speech, motor function and thought — the cells, in short, that make us who we are. In the course of his research, Sestan, an expert in developmental neurobiology, regularly ordered slices of animal and human brain tissue from various brain banks, which shipped the specimens to Yale in coolers full of ice. Sometimes the tissue arrived within three or four hours of the donor’s death. Sometimes it took more than a day. Still, Sestan and his team were able to culture, or grow, active cells from that tissue — tissue that was, for all practical purposes, entirely dead. In the right circumstances, they could actually keep the cells alive for several weeks at a stretch.

A few years ago, a scientist named Nenad Sestan began throwing around an idea for an experiment so obviously insane, so “wild” and “totally out there,” as he put it to me recently, that at first he told almost no one about it: not his wife or kids, not his bosses in Yale’s neuroscience department, not the dean of the university’s medical school. Like everything Sestan studies, the idea centered on the mammalian brain. More specific, it centered on the tree-shaped neurons that govern speech, motor function and thought — the cells, in short, that make us who we are. In the course of his research, Sestan, an expert in developmental neurobiology, regularly ordered slices of animal and human brain tissue from various brain banks, which shipped the specimens to Yale in coolers full of ice. Sometimes the tissue arrived within three or four hours of the donor’s death. Sometimes it took more than a day. Still, Sestan and his team were able to culture, or grow, active cells from that tissue — tissue that was, for all practical purposes, entirely dead. In the right circumstances, they could actually keep the cells alive for several weeks at a stretch.

When I met with Sestan this spring, at his lab in New Haven, he took great care to stress that he was far from the only scientist to have noticed the phenomenon. “Lots of people knew this,” he said. “Lots and lots.” And yet he seems to have been one of the few to take these findings and push them forward: If you could restore activity to individual post-mortem brain cells, he reasoned to himself, what was to stop you from restoring activity to entire slices of post-mortem brain?

To do so would be to create an entirely novel medium for understanding brain function. “One of the things we studied in our lab was the connectome — a kind of wiring map of the brain,” Sestan told me. Research on the connectome, which comprises the brain’s 90 billion neurons and hundreds of trillions of synapses, is widely viewed among neuroscientists as integral to understanding — and potentially treating — a range of disorders, from autism to schizophrenia. And yet there are few reliable ways of tracing all those connections in the brains of large mammals. “I thought, O.K., let’s see if this” — slices of cellularly revived brain tissue — “is the way to go,” Sestan said.

More here.

Leonard Benardo in The American Progress:

Leonard Benardo in The American Progress: Eric Foner in The Nation:

Eric Foner in The Nation: Lida Maxwell in the LA Review of Books:

Lida Maxwell in the LA Review of Books: Martin Jay in The Point:

Martin Jay in The Point: Unsurprisingly from the author of The Strangest Man, an award-winning biography of Dirac, Farmelo has offered a thoughtful, well-informed reply to those who believe the quest for mathematical beauty has led theoretical physicists into adopting sterile, ultra-mathematical approaches divorced from reality. He makes a persuasive case as he argues that theorists have not spent the last 40 years wasting their time writing quasi-scientific fairytales and that many of the ideas and concepts that have emerged will endure.

Unsurprisingly from the author of The Strangest Man, an award-winning biography of Dirac, Farmelo has offered a thoughtful, well-informed reply to those who believe the quest for mathematical beauty has led theoretical physicists into adopting sterile, ultra-mathematical approaches divorced from reality. He makes a persuasive case as he argues that theorists have not spent the last 40 years wasting their time writing quasi-scientific fairytales and that many of the ideas and concepts that have emerged will endure. Walter Bagehot — pronounced Badge-it — was first called “the greatest Victorian” by that capaciously learned historian of 19th-century England, G.M. Young. The phrase has been attached to Bagehot’s name ever since and is again used by James Grant in the subtitle of this new biography, even though it would be more accurate to call its subject “the most versatile Victorian.”

Walter Bagehot — pronounced Badge-it — was first called “the greatest Victorian” by that capaciously learned historian of 19th-century England, G.M. Young. The phrase has been attached to Bagehot’s name ever since and is again used by James Grant in the subtitle of this new biography, even though it would be more accurate to call its subject “the most versatile Victorian.” B

B It takes a little over two hours to drive from Multan, a city in southern Punjab,

It takes a little over two hours to drive from Multan, a city in southern Punjab,  On the one hand, are we really to believe a single human is responsible for the body of work — entertaining, brilliant, immense — that Neal Stephenson has produced over the past quarter-century? Turning out thousand-page novels every couple of years? It seems much more likely that a computer is behind all of this. On the other hand, have you read Neal Stephenson? His mind is capable of going places no one else has ever imagined, let alone rendered in photorealist prose. And he doesn’t just go to those places; he takes us with him. The very fact of Stephenson’s existence might be the best argument we have against the simulation hypothesis. His latest, “Fall; or, Dodge in Hell,” is another piece of evidence in the anti-Matrix case: a staggering feat of imagination, intelligence and stamina. For long stretches, at least. Between those long stretches, there are sections that, while never uninteresting, are somewhat less successful. To expect any different, especially in a work of this length, would be to hold it to an impossible standard. Somewhere in this 900-page book is a 600-page book. One that has the same story, but weighs less. Without those 300 pages, though, it wouldn’t be Neal Stephenson. It’s not possible to separate the essential from the decorative. Nor would we want that, even if it were were. Not only do his fans not mind the extra — it’s what we came for.

On the one hand, are we really to believe a single human is responsible for the body of work — entertaining, brilliant, immense — that Neal Stephenson has produced over the past quarter-century? Turning out thousand-page novels every couple of years? It seems much more likely that a computer is behind all of this. On the other hand, have you read Neal Stephenson? His mind is capable of going places no one else has ever imagined, let alone rendered in photorealist prose. And he doesn’t just go to those places; he takes us with him. The very fact of Stephenson’s existence might be the best argument we have against the simulation hypothesis. His latest, “Fall; or, Dodge in Hell,” is another piece of evidence in the anti-Matrix case: a staggering feat of imagination, intelligence and stamina. For long stretches, at least. Between those long stretches, there are sections that, while never uninteresting, are somewhat less successful. To expect any different, especially in a work of this length, would be to hold it to an impossible standard. Somewhere in this 900-page book is a 600-page book. One that has the same story, but weighs less. Without those 300 pages, though, it wouldn’t be Neal Stephenson. It’s not possible to separate the essential from the decorative. Nor would we want that, even if it were were. Not only do his fans not mind the extra — it’s what we came for. In the fall of 1941, during a stint as a visiting faculty member at the University of Michigan, the poet W.H. Auden offered an undergraduate course of staggering intellectual scope. “Fate and the Individual in European Literature,” as it was titled, is not anything he is known for. Indeed, it is a sad reflection on the preoccupations of literary biography that, while we know far more than any sane person would ever want to know about Auden’s desperately unhappy love life, we know little about the origins or trajectory of this remarkable course. It is mentioned only in passing in some of the biographical accounts of Auden’s life and in a few testimonials from students who took the course (including Kenneth Millar, better known by his detective-fiction pseudonym Ross McDonald). Otherwise, it has gone largely unnoticed or unremarked upon.

In the fall of 1941, during a stint as a visiting faculty member at the University of Michigan, the poet W.H. Auden offered an undergraduate course of staggering intellectual scope. “Fate and the Individual in European Literature,” as it was titled, is not anything he is known for. Indeed, it is a sad reflection on the preoccupations of literary biography that, while we know far more than any sane person would ever want to know about Auden’s desperately unhappy love life, we know little about the origins or trajectory of this remarkable course. It is mentioned only in passing in some of the biographical accounts of Auden’s life and in a few testimonials from students who took the course (including Kenneth Millar, better known by his detective-fiction pseudonym Ross McDonald). Otherwise, it has gone largely unnoticed or unremarked upon. “What was once considered catastrophic warming now seems like a best-case scenario,” Mr Alston said.

“What was once considered catastrophic warming now seems like a best-case scenario,” Mr Alston said. Readers who have followed several incarnations of my blogs (like

Readers who have followed several incarnations of my blogs (like  There are at least four Robert Blys. One is the poet of pure lyrics like the ones I have quoted. Then there is Bly the political poet of the Vietnam War years. After his political and antiwar poetry, Bly turned to the self-help or human potential movement. His book Iron John: A Book about Men, was a best seller, and Bly became a guru of the men’s movement. And there is at least one more Bly: the polemicist. After service in the Navy, graduation from Harvard and Iowa and a few years in New York, Bly settled in rural Minnesota where, in the tradition of poets who used their magazines to advance their views, like T. S. Eliot with The Criterion and John Crowe Ransom with the Kenyon Review, he edited his fiercely polemical magazine, The Fifties (later, predictably enough, The Sixties and The Seventies). Warmly loyal to his friends, Bly was also ready to attack, sometimes viciously, those whose approach to poetry did not agree with his.

There are at least four Robert Blys. One is the poet of pure lyrics like the ones I have quoted. Then there is Bly the political poet of the Vietnam War years. After his political and antiwar poetry, Bly turned to the self-help or human potential movement. His book Iron John: A Book about Men, was a best seller, and Bly became a guru of the men’s movement. And there is at least one more Bly: the polemicist. After service in the Navy, graduation from Harvard and Iowa and a few years in New York, Bly settled in rural Minnesota where, in the tradition of poets who used their magazines to advance their views, like T. S. Eliot with The Criterion and John Crowe Ransom with the Kenyon Review, he edited his fiercely polemical magazine, The Fifties (later, predictably enough, The Sixties and The Seventies). Warmly loyal to his friends, Bly was also ready to attack, sometimes viciously, those whose approach to poetry did not agree with his. The claim to appreciate a film exclusively on pure merit has always been spurious, for it disavows how thoroughly the very notions of achievement and relevance are shaped by power, generally to the detriment of those who have historically been excluded from the practices and institutions that build canons and criteria. There are only five films by women out of some 150 titles in the BFI Classics book series, but not because women have made no great films. Echoing filmmaker Lis Rhodes, who asked “Whose history?” it is now vital to query, “Whose classics?”

The claim to appreciate a film exclusively on pure merit has always been spurious, for it disavows how thoroughly the very notions of achievement and relevance are shaped by power, generally to the detriment of those who have historically been excluded from the practices and institutions that build canons and criteria. There are only five films by women out of some 150 titles in the BFI Classics book series, but not because women have made no great films. Echoing filmmaker Lis Rhodes, who asked “Whose history?” it is now vital to query, “Whose classics?” There are many conclusions to be drawn from the last seven months in France, but one seems unavoidable: a great many people—a majority, perhaps: silent, moral or whatever you want to call it—just don’t like Emmanuel Macron and the world he stands for. It’s only partially misleading to speak of this majority in the aggregate. There are certainly those who want to recreate the cultural makeup of some bygone France. Some of them hate immigrants and others are anti-Semitic. Still others just don’t like the cocky cosmopolitanism of a supposedly new type of elite that casts itself as modern and tolerant and is all the more self-assured because of it. But these are the shadow actors seeking to exploit a far more legitimate and widespread anger. One doesn’t need to be a pollster to pick apart what it really means when, in late December, 70 percent of people in a modern society supported a movement that for several consecutive weekends was rampaging through France’s well-off metropolitan centers and blocking critical road junctures, demanding more economic justice, redistribution, investment in public infrastructure and social services.

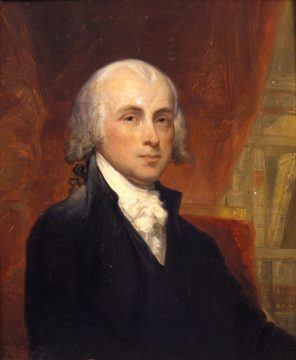

There are many conclusions to be drawn from the last seven months in France, but one seems unavoidable: a great many people—a majority, perhaps: silent, moral or whatever you want to call it—just don’t like Emmanuel Macron and the world he stands for. It’s only partially misleading to speak of this majority in the aggregate. There are certainly those who want to recreate the cultural makeup of some bygone France. Some of them hate immigrants and others are anti-Semitic. Still others just don’t like the cocky cosmopolitanism of a supposedly new type of elite that casts itself as modern and tolerant and is all the more self-assured because of it. But these are the shadow actors seeking to exploit a far more legitimate and widespread anger. One doesn’t need to be a pollster to pick apart what it really means when, in late December, 70 percent of people in a modern society supported a movement that for several consecutive weekends was rampaging through France’s well-off metropolitan centers and blocking critical road junctures, demanding more economic justice, redistribution, investment in public infrastructure and social services. In the greatest of the Federalist Papers, Number 10, James Madison explicitly pointed out the connection between liberty and inequality, and he explained why you can’t have the first without the second. Men formed governments, Madison believed (as did all the Founding Fathers), to safeguard rights that come from nature, not from government—rights to life, to liberty, and to the acquisition and ownership of property. Before we joined forces in society and chose an official cloaked with the authority to wield our collective power to restrain or punish violators of our natural rights, those rights were at constant risk of being trampled by someone stronger than we. Over time, though, those officials’ successors grew autocratic, and their governments overturned the very rights they were supposed to protect, creating a world as arbitrary as the inequality of the state of nature, in which the strongest took whatever he wanted, until someone still stronger came along.

In the greatest of the Federalist Papers, Number 10, James Madison explicitly pointed out the connection between liberty and inequality, and he explained why you can’t have the first without the second. Men formed governments, Madison believed (as did all the Founding Fathers), to safeguard rights that come from nature, not from government—rights to life, to liberty, and to the acquisition and ownership of property. Before we joined forces in society and chose an official cloaked with the authority to wield our collective power to restrain or punish violators of our natural rights, those rights were at constant risk of being trampled by someone stronger than we. Over time, though, those officials’ successors grew autocratic, and their governments overturned the very rights they were supposed to protect, creating a world as arbitrary as the inequality of the state of nature, in which the strongest took whatever he wanted, until someone still stronger came along.