Emily Singer in Simons Foundation:

As scientists record from an increasingly large number of neurons simultaneously, they are trying to understand what structure the activity pattern takes and how that structure relates to the population’s computing power. A number of studies have suggested that neuronal populations are highly correlated, producing low-dimensional patterns of activity. That observation is somewhat surprising, because minimally correlated groups of neurons would be able to transmit more information. (For more on this, see Predicting Neural Dynamics From Connectivity and The Dimension Question: How High Does It Go?)

As scientists record from an increasingly large number of neurons simultaneously, they are trying to understand what structure the activity pattern takes and how that structure relates to the population’s computing power. A number of studies have suggested that neuronal populations are highly correlated, producing low-dimensional patterns of activity. That observation is somewhat surprising, because minimally correlated groups of neurons would be able to transmit more information. (For more on this, see Predicting Neural Dynamics From Connectivity and The Dimension Question: How High Does It Go?)

In the new study, Carsen Stringer and Marius Pachitariu, now researchers at the Janelia Research Campus in Ashburn, Virginia, and previously a graduate student and postdoctoral researcher, respectively, in Harris’ lab, used two photon microscopy to simultaneously record signals from 10,000 neurons in the visual cortex of mice looking at nearly 3,000 natural images. Using a variant of principal component analysis to analyze the resulting activity, the researchers found it was neither low-dimensional nor completely uncorrelated. Rather, neuronal activity followed a power law in which each component explains a fraction of the variance of the previous component. The power law can’t simply be explained by the use of natural images, which have a power-law structure in their pixels (neighboring pixels tend to be similar). The same pattern held for white-noise stimuli.

Researchers used a branch of mathematical analysis called functional analysis to show that if the size of those dimensions decayed any slower, the code would focus more and more attention on smaller and smaller details of the stimulus, losing the big picture. In other words, the brain would no longer see the forest for the trees. Using this framework, the researchers predicted that dimensionality decays faster for simpler, lower-dimensional stimuli than for natural images. Experiments showed this is indeed the case — the slope of the power law depends on the dimensionality of the input stimuli. Harris says the approach can be applied to different types of large-scale recordings, such as place coding in the hippocampus and grid cells in the entorhinal cortex.

More here.

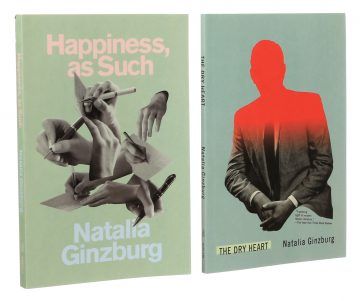

The voice is instantly, almost violently recognizable — aloof, amused and melancholy. The metaphors are sparse and ordinary; the language plain, but every word load-bearing. Short sentences detonate into scenes of shocking cruelty. Even in middling translations, it is a style that cannot be subsumed; Natalia Ginzburg can only sound like herself.

The voice is instantly, almost violently recognizable — aloof, amused and melancholy. The metaphors are sparse and ordinary; the language plain, but every word load-bearing. Short sentences detonate into scenes of shocking cruelty. Even in middling translations, it is a style that cannot be subsumed; Natalia Ginzburg can only sound like herself. When the last of a species disappears, it usually does so unnoticed, somewhere in the wild. Only later, when repeated searches come up empty, will researchers reluctantly acknowledge that the species must be extinct. But in rare cases like George’s, when people are caring for an animal’s last known representative, extinction—an often abstract concept—becomes painfully concrete. It happens on their watch, in real time. It leaves behind a body. When Sischo rang in the new year, Achatinella apexfulva existed. A day later, it did not. “It is happening right in front of our eyes,” he said.

When the last of a species disappears, it usually does so unnoticed, somewhere in the wild. Only later, when repeated searches come up empty, will researchers reluctantly acknowledge that the species must be extinct. But in rare cases like George’s, when people are caring for an animal’s last known representative, extinction—an often abstract concept—becomes painfully concrete. It happens on their watch, in real time. It leaves behind a body. When Sischo rang in the new year, Achatinella apexfulva existed. A day later, it did not. “It is happening right in front of our eyes,” he said. Human beings are the type of animal that depend upon the diversity and plenitude of other life to sustain us. It’s no coincidence that our presence arrived concomitant with the richest biota the earth has ever developed. This wealth of life created the complex and flexible niche that we’ve come to fill, not only passively, as our food source, but even actively, as symbionts living on our skin and

Human beings are the type of animal that depend upon the diversity and plenitude of other life to sustain us. It’s no coincidence that our presence arrived concomitant with the richest biota the earth has ever developed. This wealth of life created the complex and flexible niche that we’ve come to fill, not only passively, as our food source, but even actively, as symbionts living on our skin and  P

P Liu’s tomes—they tend to be tomes—have been translated into more than twenty languages, and the trilogy has sold some eight million copies worldwide. He has won China’s highest honor for science-fiction writing, the Galaxy Award, nine times, and in 2015 he became the first Asian writer to win the Hugo Award, the most prestigious international science-fiction prize. In China, one of his stories has been a set text in the gao kao—the notoriously competitive college-entrance exams that determine the fate of ten million pupils annually; another has appeared in the national seventh-grade-curriculum textbook. When a reporter recently challenged Liu to answer the middle-school questions about the “meaning” and the “central themes” of his story, he didn’t get a single one right. “I’m a writer,” he told me, with a shrug. “I don’t begin with some conceit in mind. I’m just trying to tell a good story.”

Liu’s tomes—they tend to be tomes—have been translated into more than twenty languages, and the trilogy has sold some eight million copies worldwide. He has won China’s highest honor for science-fiction writing, the Galaxy Award, nine times, and in 2015 he became the first Asian writer to win the Hugo Award, the most prestigious international science-fiction prize. In China, one of his stories has been a set text in the gao kao—the notoriously competitive college-entrance exams that determine the fate of ten million pupils annually; another has appeared in the national seventh-grade-curriculum textbook. When a reporter recently challenged Liu to answer the middle-school questions about the “meaning” and the “central themes” of his story, he didn’t get a single one right. “I’m a writer,” he told me, with a shrug. “I don’t begin with some conceit in mind. I’m just trying to tell a good story.” I first came across the work of Nabarun Bhattacharya (1948–2014) about a decade ago in Calcutta, after a long afternoon of wandering conversation of the kind that Bengalis call adda, a session that no doubt included numerous cups of tea, many cigarettes, much talk about books, films, and politics before peaking, in the evening, with kebabs and cheap Indian rum. These freewheeling hours of aimless mental flaneurie that make no concessions to modernity’s iron cage of productivity and self-improvement have their own usefulness. Somewhere in the course of that day, from the recommendations of my companions, I ended up buying a copy of Harbart.

I first came across the work of Nabarun Bhattacharya (1948–2014) about a decade ago in Calcutta, after a long afternoon of wandering conversation of the kind that Bengalis call adda, a session that no doubt included numerous cups of tea, many cigarettes, much talk about books, films, and politics before peaking, in the evening, with kebabs and cheap Indian rum. These freewheeling hours of aimless mental flaneurie that make no concessions to modernity’s iron cage of productivity and self-improvement have their own usefulness. Somewhere in the course of that day, from the recommendations of my companions, I ended up buying a copy of Harbart.

How do we structure our moving, changing thoughts and how do we structure the world we design and move and act in?

How do we structure our moving, changing thoughts and how do we structure the world we design and move and act in? As animals explore their environment, they learn to master it. By discovering what sounds tend to precede predatorial attack, for example, or what smells predict dinner, they develop a kind of biological clairvoyance—a way to anticipate what’s coming next, based on what has already transpired. Now, Rockefeller scientists have found that an animal’s education relies not only on what experiences it acquires, but also on when it acquires them. Studying

As animals explore their environment, they learn to master it. By discovering what sounds tend to precede predatorial attack, for example, or what smells predict dinner, they develop a kind of biological clairvoyance—a way to anticipate what’s coming next, based on what has already transpired. Now, Rockefeller scientists have found that an animal’s education relies not only on what experiences it acquires, but also on when it acquires them. Studying  In the United States, the name Noah Webster (1758-1843) is synonymous with the word ‘dictionary’. But it is also synonymous with the idea of America, since his first unabridged American Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1828 when Webster was 70, blatantly stirred the young nation’s thirst for cultural independence from Britain.

In the United States, the name Noah Webster (1758-1843) is synonymous with the word ‘dictionary’. But it is also synonymous with the idea of America, since his first unabridged American Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1828 when Webster was 70, blatantly stirred the young nation’s thirst for cultural independence from Britain.

The conventions of mainstream journalism make it difficult to challenge America’s self-conception as a peace-loving nation. But the unlovely truth is this: Throughout its history, America has attacked countries that did not threaten it. To carry out such wars, American leaders have contrived pretexts to justify American aggression. That’s what Donald Trump’s administration—and especially its national security adviser, John Bolton—is doing now with Iran.

The conventions of mainstream journalism make it difficult to challenge America’s self-conception as a peace-loving nation. But the unlovely truth is this: Throughout its history, America has attacked countries that did not threaten it. To carry out such wars, American leaders have contrived pretexts to justify American aggression. That’s what Donald Trump’s administration—and especially its national security adviser, John Bolton—is doing now with Iran. Griffin was referring to a revolutionary new type of weapon, one that would have the unprecedented ability to maneuver and then to strike almost any target in the world within a matter of minutes. Capable of traveling at more than 15 times the speed of sound, hypersonic missiles arrive at their targets in a blinding, destructive flash, before any sonic booms or other meaningful warning. So far, there are no surefire defenses. Fast, effective, precise and unstoppable — these are rare but highly desired characteristics on the modern battlefield. And the missiles are being developed not only by the United States but also by China, Russia and other countries.

Griffin was referring to a revolutionary new type of weapon, one that would have the unprecedented ability to maneuver and then to strike almost any target in the world within a matter of minutes. Capable of traveling at more than 15 times the speed of sound, hypersonic missiles arrive at their targets in a blinding, destructive flash, before any sonic booms or other meaningful warning. So far, there are no surefire defenses. Fast, effective, precise and unstoppable — these are rare but highly desired characteristics on the modern battlefield. And the missiles are being developed not only by the United States but also by China, Russia and other countries.

It was the

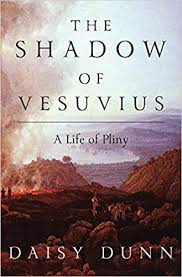

It was the  Herculaneum, a town on the Bay of Naples that was buried beneath volcanic ash when Vesuvius erupted in AD 79, has only been partially excavated. Some buildings stand open to the sky; others, such as the theatre, can only be accessed through cramped and winding tunnels; many lie entirely entombed within rock. A visitor’s reaction to this can be an interesting gauge of character. The glass-half-full person will exult in the chance to walk the streets of an ancient city. The glass-half-empty person will wish there were more streets to walk. In Herculaneum, where furniture, bread and figs were all carbonised by the pyroclastic surge, the trace elements of life as it was lived in the heyday of the Roman Empire can serve to tantalise as well as satisfy the curious. To study the distant past is always to be greedy. It is to be like Orpheus, snatching after ghosts.

Herculaneum, a town on the Bay of Naples that was buried beneath volcanic ash when Vesuvius erupted in AD 79, has only been partially excavated. Some buildings stand open to the sky; others, such as the theatre, can only be accessed through cramped and winding tunnels; many lie entirely entombed within rock. A visitor’s reaction to this can be an interesting gauge of character. The glass-half-full person will exult in the chance to walk the streets of an ancient city. The glass-half-empty person will wish there were more streets to walk. In Herculaneum, where furniture, bread and figs were all carbonised by the pyroclastic surge, the trace elements of life as it was lived in the heyday of the Roman Empire can serve to tantalise as well as satisfy the curious. To study the distant past is always to be greedy. It is to be like Orpheus, snatching after ghosts.