Corey Robin in The New Yorker:

Corey Robin in The New Yorker:

he professor and the politician are a dyad of perpetual myth. In one myth, they are locked in conflict, sparring over the claims of reason and the imperative of power. Think Socrates and Athens, or Noam Chomsky and the American state. In another myth, they are reconciled, even fused. The professor becomes a politician, saving the polity from corruption and ignorance, demagoguery and vice. Think Plato’s philosopher-king, or Aaron Sorkin’s Jed Bartlet. The nobility of ideas is preserved, and transmuted, slowly, into the stuff of action.

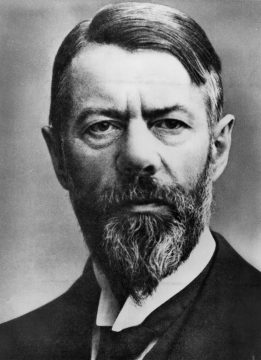

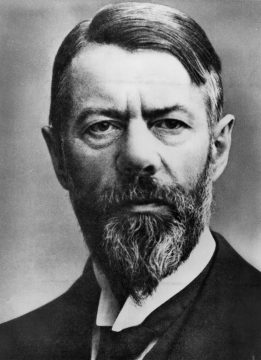

The sociologist Max Weber spent much of his life seduced by this second fable. A scholar of hot temper and volcanic energy, Weber longed to be a politician of cold focus and hard reason. Across three decades of a scholarly career, in Wilhelmine and Weimar Germany, he made repeated and often failed incursions into the public sphere—to give advice, stand for office, form a party, negotiate a treaty, and write a constitution. His “secret love,” he confessed to a friend, was “the political.” Even in the delirium of his final days, he could be heard declaiming on behalf of the German people, jousting with their enemies in several of the many languages he knew. “If one is lucky” in politics, he observed, a “genius appears just once every few hundred years.” That left the door wide open for him.

More here. And see also Patrick Thaddeus Jackson’s response over at Lawyers, Guns and Money:

1) The whole point of Weber’s “vocation” lectures was to caution his listeners against either a political or an academic “savior.” In the lecture on Wissenschaft — usually translated “science,” but the sense of the word in German is more like “systematic scholarship” — Weber takes pains to argue that other than “some overgrown children in their professorial chairs or editorial offices,” no one thinks that academic study can teach us anything about the meaning of the world. And in the lecture on politics, Weber is, if anything, more afraid of the revolutionary prophet taking over the reins of government than he is of the amoral cynic who treats politics as a means for personal enrichment:

“…people who have just preached ‘love against force’ are found calling for the use of force the very next moment. It is always the very last use of force that will then bring about a situation in which all violence will have been destroyed — just as our military leaders tell the soldiers that every offensive will be the last. This one will bring victory and then peace. The man who embraces an ethics of conviction is unable to tolerate the ethical irrationality of the world.”

More here.

Historic is not a word that should be used lightly. It should nearly never be used for anything contemporary and only sparingly for events long past. Yet, it is being used with considerable frequency to describe the 2020 US Presidential elections; maybe, not inappropriately.

Historic is not a word that should be used lightly. It should nearly never be used for anything contemporary and only sparingly for events long past. Yet, it is being used with considerable frequency to describe the 2020 US Presidential elections; maybe, not inappropriately.

Based on the last two presidential elections, there is clearly a failure in reporting, polling and understanding of almost half of America. Perhaps liberals would simply like to govern and run for office by only mobilizing their half of the population and overlooking that other half, but I would imagine this country won’t get closer to equal opportunity with that type of thinking. It’s true that much of the divisive language comes from Trump supporters who seems to enjoy Trump’s deplorable approach to life and politics. Does that embody every single person who voted for Donald Trump in the last two elections? If you think that, then you are as lost as the narrow reporting and polling I have witnessed during the last four years.

Based on the last two presidential elections, there is clearly a failure in reporting, polling and understanding of almost half of America. Perhaps liberals would simply like to govern and run for office by only mobilizing their half of the population and overlooking that other half, but I would imagine this country won’t get closer to equal opportunity with that type of thinking. It’s true that much of the divisive language comes from Trump supporters who seems to enjoy Trump’s deplorable approach to life and politics. Does that embody every single person who voted for Donald Trump in the last two elections? If you think that, then you are as lost as the narrow reporting and polling I have witnessed during the last four years. When Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer exchanged vows on July 29, 1981, the archbishop officiating the ceremony

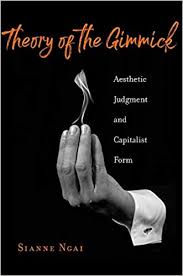

When Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer exchanged vows on July 29, 1981, the archbishop officiating the ceremony  Although Ngai’s books are conceptually and philosophically dense, their appeal comes from how they tap into our ordinary use of language. Unless I collect art, or live in a many-windowed house at the edge of a westerly peninsula, where the sea is gilded by the sun and silvered by the moon, I am unlikely to have regular encounters with things I would call “beautiful” or “sublime,” and I may well find the rush and roar of such Romantic descriptions embarrassing. But not a day goes by when I do not call something—my son’s stuffed animals, a dress, a poem by Gertrude Stein—“cute,” or a novel or an essay “interesting.” And I can’t count the number of times I’ve called a kitchen gizmo my husband swears we really, really need (but we really, really don’t) or a colleague’s online persona “gimmicky.” “Theory of the Gimmick” finds in the pervasiveness of the gimmick the same duelling forces of aesthetic attraction and repulsion that shape all Ngai’s work. “ ‘You want me,’ the gimmick outrageously says,” she writes. “It is never entirely wrong.”

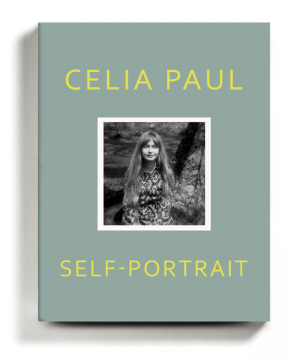

Although Ngai’s books are conceptually and philosophically dense, their appeal comes from how they tap into our ordinary use of language. Unless I collect art, or live in a many-windowed house at the edge of a westerly peninsula, where the sea is gilded by the sun and silvered by the moon, I am unlikely to have regular encounters with things I would call “beautiful” or “sublime,” and I may well find the rush and roar of such Romantic descriptions embarrassing. But not a day goes by when I do not call something—my son’s stuffed animals, a dress, a poem by Gertrude Stein—“cute,” or a novel or an essay “interesting.” And I can’t count the number of times I’ve called a kitchen gizmo my husband swears we really, really need (but we really, really don’t) or a colleague’s online persona “gimmicky.” “Theory of the Gimmick” finds in the pervasiveness of the gimmick the same duelling forces of aesthetic attraction and repulsion that shape all Ngai’s work. “ ‘You want me,’ the gimmick outrageously says,” she writes. “It is never entirely wrong.” “Self-Portrait” is Paul’s account of her life and her work — or, more precisely, of her attempts to realize the possibilities of each despite the constraints thrown up by the other. She left Frank with her mother in Cambridge when he was an infant. When Paul spends time with him, she says, “I don’t have any thoughts for myself.” She lives separately from her current husband, who doesn’t have a key to her flat.

“Self-Portrait” is Paul’s account of her life and her work — or, more precisely, of her attempts to realize the possibilities of each despite the constraints thrown up by the other. She left Frank with her mother in Cambridge when he was an infant. When Paul spends time with him, she says, “I don’t have any thoughts for myself.” She lives separately from her current husband, who doesn’t have a key to her flat. Corey Robin in The New Yorker:

Corey Robin in The New Yorker: Jon Stewart in Aeon:

Jon Stewart in Aeon: A few hours before

A few hours before  LAST TUESDAY NIGHT,

LAST TUESDAY NIGHT,  When I saw QAnon, I knew exactly what it was and what it was doing. I had seen it before. I had almost built it before. It was gaming’s evil twin. A game that plays people. (cue ominous music)

When I saw QAnon, I knew exactly what it was and what it was doing. I had seen it before. I had almost built it before. It was gaming’s evil twin. A game that plays people. (cue ominous music)

Pakistan was created in 1947 as a homeland for the Muslims of Hindu-majority India—“carved from the flanks of British India,” as Mr. Walsh puts it. Its “Great Leader” (“Quaid-e-Azam” in Urdu) was Muhammad Ali Jinnah, an unlikely agitator for a confessional Muslim state. A worldly lawyer who drank alcohol and married outside his faith, he was, Mr. Walsh tells us, “purposefully vague about his beliefs” for much of his life. In a poignant passage, Mr. Walsh parses a photograph of Jinnah taken in September 1947, a month after Pakistan was born: In it, he wears “the gaze of a man who gambled at the table of history, won big—and now wonders whether he won more than he bargained for.”

Pakistan was created in 1947 as a homeland for the Muslims of Hindu-majority India—“carved from the flanks of British India,” as Mr. Walsh puts it. Its “Great Leader” (“Quaid-e-Azam” in Urdu) was Muhammad Ali Jinnah, an unlikely agitator for a confessional Muslim state. A worldly lawyer who drank alcohol and married outside his faith, he was, Mr. Walsh tells us, “purposefully vague about his beliefs” for much of his life. In a poignant passage, Mr. Walsh parses a photograph of Jinnah taken in September 1947, a month after Pakistan was born: In it, he wears “the gaze of a man who gambled at the table of history, won big—and now wonders whether he won more than he bargained for.”