Category: Archives

Seigneur Moments: On Martin Amis

Kevin Power at the Dublin Review of Books:

“There is only one school,” Amis has said, “that of talent.” Only the talented would ever think this, and only the supremely talented would ever say it out loud. Inside Story is subtitled How to Write. But Amis has been telling us how to write for half a century now, and not just in his criticism. The virtuoso is always also a pedagogue. Look – this is how you do it! And the feudal lord – the seigneur – is, by definition, an aristocrat (and, not incidentally, by definition male): “rangy, well-travelled, big-cocked”, in the mocking, but also not-quite-mocking, words of Charles Highway in The Rachel Papers (1973). When Amis fails, this seigneurialism is what he’s left with: all those epigrams! All those cringey jokes! That tone of sneering condescension! (See Yellow Dog, The Pregnant Widow, Lionel Asbo. Seigneurialism – anathematised as “male privilege” – is what feminist critics have tended to find so rebarbative in Amis’s work, and they’re not wrong.) When he succeeds, the seigneurialism is merely part of the effect (see Money, London Fields, Time’s Arrow, almost all of the nonfiction).

“There is only one school,” Amis has said, “that of talent.” Only the talented would ever think this, and only the supremely talented would ever say it out loud. Inside Story is subtitled How to Write. But Amis has been telling us how to write for half a century now, and not just in his criticism. The virtuoso is always also a pedagogue. Look – this is how you do it! And the feudal lord – the seigneur – is, by definition, an aristocrat (and, not incidentally, by definition male): “rangy, well-travelled, big-cocked”, in the mocking, but also not-quite-mocking, words of Charles Highway in The Rachel Papers (1973). When Amis fails, this seigneurialism is what he’s left with: all those epigrams! All those cringey jokes! That tone of sneering condescension! (See Yellow Dog, The Pregnant Widow, Lionel Asbo. Seigneurialism – anathematised as “male privilege” – is what feminist critics have tended to find so rebarbative in Amis’s work, and they’re not wrong.) When he succeeds, the seigneurialism is merely part of the effect (see Money, London Fields, Time’s Arrow, almost all of the nonfiction).

more here.

The Story of Joy Division

Pippa Bailey at The New Statesman:

The story of Joy Division, and later New Order, is repeated so often it feels more like myth than reality. Maxine Peake’s voice is full of whispered awe as she leads us through a story that begins with three simple words – “Band seeks singer” – and ends with the making of the iconic “Blue Monday”.

The story of Joy Division, and later New Order, is repeated so often it feels more like myth than reality. Maxine Peake’s voice is full of whispered awe as she leads us through a story that begins with three simple words – “Band seeks singer” – and ends with the making of the iconic “Blue Monday”.

Transmissions takes in Factory Records, Unknown Pleasures, Ian Curtis’s suicide and the Haçienda, with interviews from Peter Hook, Stephen Morris, Bernard Sumner and others. It’s a story about Manchester, too, given authenticity by Peake’s Mancunian accent. (“There is a wilfulness in the psyche of Manchester,” says Peter Saville, and I imagine Andy Burnham nodding furiously.) For those who know this story well, there’s little new here, but it’s a joy all the same.

more here.

Joy Division – Unknown Pleasures 1979

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7vUDCZ6NePg&ab_channel=GermanLGonz%C3%A1lezA

When I Step Outside, I Step Into a Country of Men Who Stare

Fatima Bhojani in The New York Times:

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan — I am angry. All the time. I’ve been angry for years. Ever since I began to grasp the staggering extent of violence — emotional, mental and physical — against women in Pakistan. Women here, all 100 million of us, exist in collective fury. “Every day, I am reminded of a reason I shouldn’t exist,” my 19-year-old friend recently told me in a cafe in Islamabad. When she gets into an Uber, she sits right behind the driver so that he can’t reach back and grab her. We agreed that we would jump out of a moving car if that ever happened. We debated whether pepper spray was better than a knife. When I step outside, I step into a country of men who stare. I could be making the short walk from my car to the bookstore or walking through the aisles at the supermarket. I could be wrapped in a shawl or behind two layers of face mask. But I will be followed by searing eyes, X-raying me. Because here, it is culturally acceptable for men to gape at women unblinkingly, as if we are all in a staring contest that nobody told half the population about, a contest hinged on a subtle form of psychological violence.

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan — I am angry. All the time. I’ve been angry for years. Ever since I began to grasp the staggering extent of violence — emotional, mental and physical — against women in Pakistan. Women here, all 100 million of us, exist in collective fury. “Every day, I am reminded of a reason I shouldn’t exist,” my 19-year-old friend recently told me in a cafe in Islamabad. When she gets into an Uber, she sits right behind the driver so that he can’t reach back and grab her. We agreed that we would jump out of a moving car if that ever happened. We debated whether pepper spray was better than a knife. When I step outside, I step into a country of men who stare. I could be making the short walk from my car to the bookstore or walking through the aisles at the supermarket. I could be wrapped in a shawl or behind two layers of face mask. But I will be followed by searing eyes, X-raying me. Because here, it is culturally acceptable for men to gape at women unblinkingly, as if we are all in a staring contest that nobody told half the population about, a contest hinged on a subtle form of psychological violence.

…This country fails its women from the very top of government leadership to those who live with us in our homes. In September, a woman was raped beside a major highway near Lahore, Pakistan’s second-largest city. Around 1 a.m., her car ran out of fuel. She called the police and waited. Two armed men broke through the windows and assaulted her in a nearby field. The most senior police official in Lahore remarked that the survivor was assaulted because, he assumed, she “was traveling late at night without her husband’s permission.” An elderly woman in my apartment building in Islamabad, remarked, “Apni izzat apnay haath mein” — Your honor is in your own hands. In Pakistan, sexual assault comes with stigma, the notion that a woman by being on the receiving end of a violent crime has brought shame to herself and her family. Societal judgment is a major reason survivors don’t come forward. Responding to the Lahore assault, Prime Minister Imran Khan proposed chemical castration of the rapists. His endorsement of archaic punishments rather than a sincere promise to undertake the difficult, lengthy and necessary work of reforming criminal and legal procedures is part of the problem. The conviction rate for sexual assault is around 3 percent, according to War Against Rape, a local nonprofit.

More here.

Should America Still Police the World?

Daniel Immerwahr in The New Yorker:

Robert Gates’s first memoir was titled “From the Shadows,” and that is an apt description of where Gates has comfortably resided. He is not a flashy man—a colleague once likened him to “the guy at P. C. Richards who sold microwave ovens”—but he has been for decades a quietly persistent presence in foreign policymaking. Gates has served as the Defense Secretary, C.I.A. chief, and deputy national-security adviser, among other roles. Unusually, he has occupied high positions under both Democratic and Republican Presidents. After George W. Bush placed him in charge of the Defense Department, Barack Obama kept him there as a trusted source of counsel. He has called Biden “a man of genuine integrity” and Trump “unfit to be Commander-in-Chief.”

Robert Gates’s first memoir was titled “From the Shadows,” and that is an apt description of where Gates has comfortably resided. He is not a flashy man—a colleague once likened him to “the guy at P. C. Richards who sold microwave ovens”—but he has been for decades a quietly persistent presence in foreign policymaking. Gates has served as the Defense Secretary, C.I.A. chief, and deputy national-security adviser, among other roles. Unusually, he has occupied high positions under both Democratic and Republican Presidents. After George W. Bush placed him in charge of the Defense Department, Barack Obama kept him there as a trusted source of counsel. He has called Biden “a man of genuine integrity” and Trump “unfit to be Commander-in-Chief.”

Gates’s latest book, “Exercise of Power,” offers a stark view of the world. The country is “challenged on every front,” Gates believes. The places the United States must police are, in his various descriptions, a “bane” (Iran), a “curse” (Iraq), a “primitive country” (Afghanistan), and a “sinkhole of conflict and terrorism” (the Middle East). Its adversaries form a rogue’s gallery of “bad guys,” “thugs,” “serial cheaters and liars,” and “ever-duplicitous Pakistanis.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Untitled

Lord,

……… when you send the rain,

……… think about it, please,

……… a little?

Do

……… not get carried away

……… by the sound of falling water,

……… the marvelous light

……… on the falling water.

I

……… am beneath that water.

……… It falls with great force

……… and the light

Blinds

……… me to the light.

by James Baldwin – 1924-1987

Tuesday, November 17, 2020

Buster Keaton Falls Up

John Plotz in Public Books:

Comedy inverts norms and breaks barriers. But in order to reveal, as Northrop Frye suggested it must, “absurd or irrational [patriarchal] law,” comedy requires a fall guy. There has to be somebody on whom that law can come crashing down, in all its absurdity, all its irrationality—somebody who improbably emerges at the end, unscathed or even triumphant. Buster Keaton, that beautifully deadpan clown known as “The Great Stone Face,” had the pliability—and the subtle anarchic capacity for nonviolent resistance—to fill that role like nobody else before him. Or since.

Comedy inverts norms and breaks barriers. But in order to reveal, as Northrop Frye suggested it must, “absurd or irrational [patriarchal] law,” comedy requires a fall guy. There has to be somebody on whom that law can come crashing down, in all its absurdity, all its irrationality—somebody who improbably emerges at the end, unscathed or even triumphant. Buster Keaton, that beautifully deadpan clown known as “The Great Stone Face,” had the pliability—and the subtle anarchic capacity for nonviolent resistance—to fill that role like nobody else before him. Or since.

Keaton is remembered now as a brilliant stuntman and inventor of trick shots (see, for instance, the cutaway walls of the house in 1921’s The High Sign). However, his true genius resides in his delightful disorientation from—and re-orientation to—a world that is never quite what he takes it to be.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Lisa Feldman Barrett on Emotions, Actions, and the Brain

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Emotions are at the same time utterly central to who we are — where would we be without them? — and also seemingly peripheral to the “real” work our brains do, understanding the world and acting within it. Why do we have emotions, anyway? Are they hardwired into the brain? Lisa Feldman Barrett is one of the world’s leading experts in the psychology of emotions, and she emphasizes that they are more constructed and less hard-wired than you might think. How we feel and express emotions can vary from culture to culture or even person to person. It’s better to think of emotions of a link between affective response and our behaviors.

Emotions are at the same time utterly central to who we are — where would we be without them? — and also seemingly peripheral to the “real” work our brains do, understanding the world and acting within it. Why do we have emotions, anyway? Are they hardwired into the brain? Lisa Feldman Barrett is one of the world’s leading experts in the psychology of emotions, and she emphasizes that they are more constructed and less hard-wired than you might think. How we feel and express emotions can vary from culture to culture or even person to person. It’s better to think of emotions of a link between affective response and our behaviors.

More here.

Huawei, 5G, and the Man Who Conquered Noise

Steven Levy in Wired:

ERDAL ARIKAN was born in 1958 and grew up in Western Turkey, the son of a doctor and a homemaker. He loved science. When he was a teenager, his father remarked that, in his profession, two plus two did not always equal four. This fuzziness disturbed young Erdal; he decided against a career in medicine. He found comfort in engineering and the certainty of its mathematical outcomes. “I like things that have some precision,” he says. “You do calculations and things turn out as you calculate it.”

ERDAL ARIKAN was born in 1958 and grew up in Western Turkey, the son of a doctor and a homemaker. He loved science. When he was a teenager, his father remarked that, in his profession, two plus two did not always equal four. This fuzziness disturbed young Erdal; he decided against a career in medicine. He found comfort in engineering and the certainty of its mathematical outcomes. “I like things that have some precision,” he says. “You do calculations and things turn out as you calculate it.”

Arıkan entered the electrical engineering program at Middle East Technical University. But in 1977, partway through his first year, the country was gripped by political violence, and students boycotted the university. Arıkan wanted to study, and because of his excellent test scores he managed to transfer to CalTech, one of the world’s top science-oriented institutions, in Pasadena, California. He found the US to be a strange and wonderful country. Within his first few days, he was in an orientation session addressed by legendary physicist Richard Feynman. It was like being blessed by a saint.

More here.

Glenn Greenwald on the Dangers of the Coming Biden/Harris Administration

Top 10 Emerging Technologies of 2020

From Scientific American:

If some of the many thousands of human volunteers needed to test coronavirus vaccines could have been replaced by digital replicas—one of this year’s Top 10 Emerging Technologies—COVID-19 vaccines might have been developed even faster, saving untold lives. Soon virtual clinical trials could be a reality for testing new vaccines and therapies. Other technologies on the list could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by electrifying air travel and enabling sunlight to directly power the production of industrial chemicals. With “spatial” computing, the digital and physical worlds will be integrated in ways that go beyond the feats of virtual reality. And ultrasensitive sensors that exploit quantum processes will set the stage for such applications as wearable brain scanners and vehicles that can see around corners.

If some of the many thousands of human volunteers needed to test coronavirus vaccines could have been replaced by digital replicas—one of this year’s Top 10 Emerging Technologies—COVID-19 vaccines might have been developed even faster, saving untold lives. Soon virtual clinical trials could be a reality for testing new vaccines and therapies. Other technologies on the list could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by electrifying air travel and enabling sunlight to directly power the production of industrial chemicals. With “spatial” computing, the digital and physical worlds will be integrated in ways that go beyond the feats of virtual reality. And ultrasensitive sensors that exploit quantum processes will set the stage for such applications as wearable brain scanners and vehicles that can see around corners.

These and the other emerging technologies have been singled out by an international steering group of experts. The group, convened by Scientific American and the World Economic Forum, sifted through more than 75 nominations. To win the nod, the technologies must have the potential to spur progress in societies and economies by outperforming established ways of doing things. They also need to be novel (that is, not currently in wide use) yet likely to have a major impact within the next three to five years. The steering group met (virtually) to whittle down the candidates and then closely evaluate the front-runners before making the final decisions. We hope you are as inspired by the reports that follow as we are.

- MICRONEEDLES COULD ENABLE PAINLESS INJECTIONS AND BLOOD DRAWS

- SUN-POWERED CHEMISTRY CAN TURN CARBON DIOXIDE INTO COMMON MATERIALS

- VIRTUAL PATIENTS COULD REVOLUTIONIZE MEDICINE

- SPATIAL COMPUTING COULD BE THE NEXT BIG THING

- DIGITAL MEDICINE CAN DIAGNOSE AND TREAT WHAT AILS YOU

- ELECTRIC AVIATION COULD BE CLOSER THAN YOU THINK

- LOW-CARBON CEMENT CAN HELP COMBAT CLIMATE CHANGE

- QUANTUM SENSORS COULD LET AUTONOMOUS CARS ‘SEE’ AROUND CORNERS

- GREEN HYDROGEN COULD FILL BIG GAPS IN RENEWABLE ENERGY

- WHOLE-GENOME SYNTHESIS WILL TRANSFORM CELL ENGINEERING

More here.

We Are Built to Forget

Meredith Hall in Paris Review:

We remember and we forget. Lots of people know that marijuana makes us forget, and researchers in the sixties and seventies wanted to understand how. They discovered that the human brain has special receptors that perfectly fit psychoactive chemicals like THC, the active agent in cannabis. But why, they wondered, would we have neuroreceptors for a foreign substance? We don’t. Those receptors are for substances produced in our own brains. The researchers discovered that we produce cannabinoids, our own version of THC, that fit those receptors exactly. The scientists had stumbled onto the neurochemical function of forgetting, never before understood. We are designed, they realized, not only to remember but also to forget. The first of the neurotransmitters discovered was named anandamide, Sanskrit for bliss.

We remember and we forget. Lots of people know that marijuana makes us forget, and researchers in the sixties and seventies wanted to understand how. They discovered that the human brain has special receptors that perfectly fit psychoactive chemicals like THC, the active agent in cannabis. But why, they wondered, would we have neuroreceptors for a foreign substance? We don’t. Those receptors are for substances produced in our own brains. The researchers discovered that we produce cannabinoids, our own version of THC, that fit those receptors exactly. The scientists had stumbled onto the neurochemical function of forgetting, never before understood. We are designed, they realized, not only to remember but also to forget. The first of the neurotransmitters discovered was named anandamide, Sanskrit for bliss.

…People suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder are often unable to forget the causative trauma. What if we could simply erase that moment, expunge it as if it never happened? Researchers are working to develop drugs that will mimic the cannabinoids produced in the brain, pharmaceuticals that will find their way to those waiting receptors and lock in—click—a perfect fit. Release from memory. Oblivion. Bliss.

Scientists with hard hearts can create mice with unusually high and unusually low levels of cannabinoids. In one experiment, the mice were subjected to a loud sound followed by an electric shock to their feet. The mice with low levels of cannabinoids remembered what was coming. An echo in their tiny brains warned them of harm on its way. They froze at the loud sound, with apparent dread. But the mice with high levels of cannabinoids didn’t freeze. The shock that followed was news each time. Which is the blessing—the memory of pain and with it the dread, the ability to make adjustments to keep ourselves safe? Or the bliss of forgetting, never imagining the harm that is coming?

More here.

Tuesday Poem

“The older I get the more I see how our struggles as Indigenous people take root in colonialism and capitalism.” —Tanaya Winder

Becoming a Ghost

Ask me about the time

my brother ran towards the sun

arms outstretched. His shadow chased him

from corner store to church

where he offered himself in pieces.

Ask me about the time

my brother disappeared. At 16,

tossed his heartstrings over telephone wire,

dangling for all the rez dogs to feed on.

Bit by bit. The world took chunks of

my brother’s flesh.

Ask me about the first time

we drowned in history. 8 years old

during communion we ate the body of Christ

with palms wide open, not expecting wine to be

poured into our mouths. The bitterness

buried itself in my tongue and my brother

never quite lost his thirst for blood or vanishing

for more days than a shadow could hold.

Ask me if I’ve ever had to use

bottle caps as breadcrumbs to help

my brother find his way back home.

He never could tell the taste between

a scar and its wounding, an angel or demon.

Ask me if I can still hear his

exhaled prayers: I am still waiting to be found.

To be found, tell me why there is nothing

more holy than becoming a ghost.

by Tanaya Winder

from the Academy of American Poets, 2020

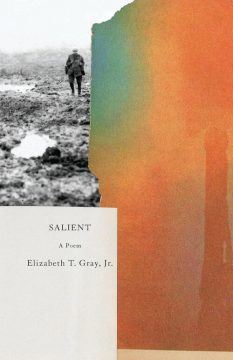

A Conversation with Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr.

Eugene Ostashevsky and Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr. at Music & Literature:

Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr., would seem to write discrete lyrics but no reader gets far in her work without succumbing to an overwhelming sense that a quest is relentlessly underway. It’s a quest that can only be fathomed through a total immersion in history and landscape and immediate psychic needs of those en route: kids out for a journey to the east, soldiers heading into death, the somewhat hidden but ever present presiding consciousness of her two long poems, Series India and Salient, the poet herself as a pained and adamant devotee to some ancient faith on a pilgrimage to the edge of the abyss. The immersion is at times so deep that we might doubt the existence of the wisdom that the figures in her poems are in search of and that the poet herself feels an unassuageable need for, and yet the force of the imagination brought to bear on this imperative for transcendence, and the acute mastery of cadence, phrasing, and image, make us want it too: to see the other side of death, to feel within ourselves some ecstatic completion.

Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr., would seem to write discrete lyrics but no reader gets far in her work without succumbing to an overwhelming sense that a quest is relentlessly underway. It’s a quest that can only be fathomed through a total immersion in history and landscape and immediate psychic needs of those en route: kids out for a journey to the east, soldiers heading into death, the somewhat hidden but ever present presiding consciousness of her two long poems, Series India and Salient, the poet herself as a pained and adamant devotee to some ancient faith on a pilgrimage to the edge of the abyss. The immersion is at times so deep that we might doubt the existence of the wisdom that the figures in her poems are in search of and that the poet herself feels an unassuageable need for, and yet the force of the imagination brought to bear on this imperative for transcendence, and the acute mastery of cadence, phrasing, and image, make us want it too: to see the other side of death, to feel within ourselves some ecstatic completion.

Her first book, Series India, reveled in the counterpointing of two realities—that of the naïve and pained journeyers with that of an uncompromising narrative intelligence devoted to the divine. The book moves back and forth between the authentic pains and foibles of the partially informed on a spiritual spree, and the informed curiosities of a poet deeply at home in thinking about ritual practice, worship, and yes, the fate of the soul.

more here.

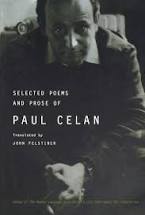

Reading Paul Celan

Ruth Franklin at The New Yorker:

From his iconic “Deathfugue,” one of the first poems published about the Nazi camps and now recognized as a benchmark of twentieth-century European poetry, to cryptic later works such as the poem above, all of Celan’s poetry is elliptical, ambiguous, resisting easy interpretation. Perhaps for this reason, it has been singularly compelling to critics and translators, who often speak of Celan’s work in quasi-religious terms. Felstiner said that, when he first encountered the poems, he knew he’d have to immerse himself in them “before doing anything else.” Pierre Joris, in the introduction to “Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), his new translation of Celan’s first four published books, writes that hearing Celan’s poetry read aloud, at the age of fifteen, set him on a path that he followed for fifty years.

From his iconic “Deathfugue,” one of the first poems published about the Nazi camps and now recognized as a benchmark of twentieth-century European poetry, to cryptic later works such as the poem above, all of Celan’s poetry is elliptical, ambiguous, resisting easy interpretation. Perhaps for this reason, it has been singularly compelling to critics and translators, who often speak of Celan’s work in quasi-religious terms. Felstiner said that, when he first encountered the poems, he knew he’d have to immerse himself in them “before doing anything else.” Pierre Joris, in the introduction to “Memory Rose Into Threshold Speech” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), his new translation of Celan’s first four published books, writes that hearing Celan’s poetry read aloud, at the age of fifteen, set him on a path that he followed for fifty years.

more here.

With Paul Celan into the 21st Century: Pierre Joris

Sunday, November 15, 2020

Philosophy’s Failure to Do Nature Justice

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

Among the Domitian questions I enjoy freely pondering, I sometimes wonder how our religious and metaphysical representations of the afterlife would be different if, rather than dying and leaving a rotting corpse for others to dispose of, we instead disappeared in a flash of light, or floated upwards into the sky and out beyond the atmosphere. It recently occurred to me that this latter scenario is at least something like what whales experience when their loved ones die.

Among the Domitian questions I enjoy freely pondering, I sometimes wonder how our religious and metaphysical representations of the afterlife would be different if, rather than dying and leaving a rotting corpse for others to dispose of, we instead disappeared in a flash of light, or floated upwards into the sky and out beyond the atmosphere. It recently occurred to me that this latter scenario is at least something like what whales experience when their loved ones die.

We think of aquatic animals as being able to move freely not just to and fro, but also up and down. In fact most are confined to a fairly narrow zone outside of which they could not survive, either because of the adaptation of their bodies to a particular amount of water pressure, their need for light or for the absence of light, or some other reason still. Most cetacean species inhabit a narrow band of water between the surface and the mesopelagic zone, characterised by a certain amount of light, but no photosynthetic microorganisms. Blue whales, a fairly average species in this regard, can dive to about 300 metres. Sperm whales and certain beaked whales hold the deep-dive record, descending 2500 metres or so to hunt for giant squid and other prey in the abyssopelagic zone.

More here.

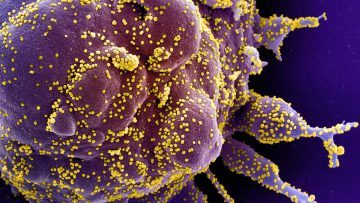

Will the Coronavirus Evolve to Be Less Deadly?

Wendy Orent in Undark:

As far as scientists and historians can tell, the bacterium that caused the Black Death never lost its virulence, or deadliness. But the pathogen responsible for the 1918 influenza pandemic, which still wanders the planet as a strain of seasonal flu, evolved to become less deadly, and it’s possible that the pathogen for the 2009 H1N1 pandemic did the same. Will SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, follow a similar trajectory? Some scientists say the virus has already evolved in a way that makes it easier to transmit. But as for a possible decline in virulence, most everyone says it’s too soon to tell. Looking to the past, however, may offer some clues.

As far as scientists and historians can tell, the bacterium that caused the Black Death never lost its virulence, or deadliness. But the pathogen responsible for the 1918 influenza pandemic, which still wanders the planet as a strain of seasonal flu, evolved to become less deadly, and it’s possible that the pathogen for the 2009 H1N1 pandemic did the same. Will SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, follow a similar trajectory? Some scientists say the virus has already evolved in a way that makes it easier to transmit. But as for a possible decline in virulence, most everyone says it’s too soon to tell. Looking to the past, however, may offer some clues.

The idea that circulating pathogens gradually become less deadly over time is very old. It seems to have originated in the writings of a 19th-century physician, Theobald Smith, who first suggested that there is a “delicate equilibrium” between parasite and host, and argued that, over time, the deadliness of a pathogen should decline since it is really not in the interest of a germ to kill its host. This notion became conventional wisdom for many years, but by the 1980s, researchers had begun challenging the idea.

More here.

The Rise of Vetocracy

Eric B. Schnurer in The Hedgehog Review:

Government has descended into near-permanent deadlock. The resulting populist movements, on both the right and left, are highly democratic: intensely broad-based and grassroots, and at least rhetorically anti-elite. But they are neither liberal nor tolerant. On an operational level, it has become more important to “own the libs” or “cancel conservatives” than to achieve any meaningful objective, let alone compromise. All opposition is now treated as an existential threat.

Government has descended into near-permanent deadlock. The resulting populist movements, on both the right and left, are highly democratic: intensely broad-based and grassroots, and at least rhetorically anti-elite. But they are neither liberal nor tolerant. On an operational level, it has become more important to “own the libs” or “cancel conservatives” than to achieve any meaningful objective, let alone compromise. All opposition is now treated as an existential threat.

Yet the increasing acceptance of incivility, the denigration and ridicule of opponents, the political violence and even death threats against anyone who takes a position that someone dislikes isn’t the problem itself. It’s simply the iceberg’s tip of a deeper and larger social phenomenon that constitutes our new normal. That new normal, in short, rather than either autocracy or democracy, is vetocracy: Thomas Hobbes’s “state of nature,” but one in which weak and strong alike can thwart each other’s objectives yet none can attain their own.

More here.