Category: Archives

Sontag & Rieff

David Mikics at Salmagundi:

There she stands, the fortysomething Susan Sontag, at a rock ‘n’ roll show in a packed New York club, encircled by sweaty kids. “Being the oldest person in a room did not make her self-conscious,” writes Sigrid Nunez in her memoir Sempre Susan. “The idea that she could ever be out of place anywhere because of her age was beyond her—like the idea that she could ever be de trop.” Sontag gave herself a regal, Oscar-Wilde-like permission to be at the center of things. That could be charming, much of the time. Other traits were less appealing. Sontag used to forbid her son David to look out of the window during train trips because, after all, there was nothing interesting about nature. Read a book instead, or, better, talk to me! was her message.

There she stands, the fortysomething Susan Sontag, at a rock ‘n’ roll show in a packed New York club, encircled by sweaty kids. “Being the oldest person in a room did not make her self-conscious,” writes Sigrid Nunez in her memoir Sempre Susan. “The idea that she could ever be out of place anywhere because of her age was beyond her—like the idea that she could ever be de trop.” Sontag gave herself a regal, Oscar-Wilde-like permission to be at the center of things. That could be charming, much of the time. Other traits were less appealing. Sontag used to forbid her son David to look out of the window during train trips because, after all, there was nothing interesting about nature. Read a book instead, or, better, talk to me! was her message.

Susan Sontag was a case, all right, as Benjamin Moser’s new biography, Sontag: Her Life and Work makes clear. But she was also interesting in ways that Moser, with his taste for the tawdry and the sensational, is ill-equipped to explore.

more here.

Sontag & Rieff

David Mikics at Salmagundi:

There she stands, the fortysomething Susan Sontag, at a rock ‘n’ roll show in a packed New York club, encircled by sweaty kids. “Being the oldest person in a room did not make her self-conscious,” writes Sigrid Nunez in her memoir Sempre Susan. “The idea that she could ever be out of place anywhere because of her age was beyond her—like the idea that she could ever be de trop.” Sontag gave herself a regal, Oscar-Wilde-like permission to be at the center of things. That could be charming, much of the time. Other traits were less appealing. Sontag used to forbid her son David to look out of the window during train trips because, after all, there was nothing interesting about nature. Read a book instead, or, better, talk to me! was her message.

There she stands, the fortysomething Susan Sontag, at a rock ‘n’ roll show in a packed New York club, encircled by sweaty kids. “Being the oldest person in a room did not make her self-conscious,” writes Sigrid Nunez in her memoir Sempre Susan. “The idea that she could ever be out of place anywhere because of her age was beyond her—like the idea that she could ever be de trop.” Sontag gave herself a regal, Oscar-Wilde-like permission to be at the center of things. That could be charming, much of the time. Other traits were less appealing. Sontag used to forbid her son David to look out of the window during train trips because, after all, there was nothing interesting about nature. Read a book instead, or, better, talk to me! was her message.

Susan Sontag was a case, all right, as Benjamin Moser’s new biography, Sontag: Her Life and Work makes clear. But she was also interesting in ways that Moser, with his taste for the tawdry and the sensational, is ill-equipped to explore.

more here.

Solzhenitsyn’s Memoirs

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn at The Hudson Review:

But, more importantly: the artist does not in fact require too detailed a study of his predecessors. It was only by fencing myself off, and not knowing most of what was written before me, that I’ve been able to fulfill my great task: otherwise you wear out and dissolve in it and accomplish nothing. If I’d read The Magic Mountain (and I still haven’t), it might somehow have impeded my writing of Cancer Ward. I was saved by the fact that my self-propelled development didn’t get distorted. I have always been hungry for reading, for knowledge—but in my school years in the provinces, when I was freer, I didn’t have that sort of guidance or access to that sort of library. And starting from my student years, my life was swallowed up by mathematics. I’d just set up a fragile connection with the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature and History when the war came, then prison, the camps, internal exile, and teaching—still mathematics, but physics too (preparing experiments for demonstration in class, which I found very difficult). And years and years of conspiring under pressure and racing, underground, to complete my books, for the sake of all those who’d died without a chance to speak. In my life I’ve had to gain a thorough grounding in artillery, oncology, the First World War, and then prerevolutionary Russia too, which by then was so impossible to imagine.

But, more importantly: the artist does not in fact require too detailed a study of his predecessors. It was only by fencing myself off, and not knowing most of what was written before me, that I’ve been able to fulfill my great task: otherwise you wear out and dissolve in it and accomplish nothing. If I’d read The Magic Mountain (and I still haven’t), it might somehow have impeded my writing of Cancer Ward. I was saved by the fact that my self-propelled development didn’t get distorted. I have always been hungry for reading, for knowledge—but in my school years in the provinces, when I was freer, I didn’t have that sort of guidance or access to that sort of library. And starting from my student years, my life was swallowed up by mathematics. I’d just set up a fragile connection with the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature and History when the war came, then prison, the camps, internal exile, and teaching—still mathematics, but physics too (preparing experiments for demonstration in class, which I found very difficult). And years and years of conspiring under pressure and racing, underground, to complete my books, for the sake of all those who’d died without a chance to speak. In my life I’ve had to gain a thorough grounding in artillery, oncology, the First World War, and then prerevolutionary Russia too, which by then was so impossible to imagine.

more here.

Friday Poem

Capitalist Poem #57

Like a sailor practicing knots in the darkness,

like a warrior sharpening his blade in the lull of battle,

like a blind man searching out the figure of a sleeping lover

the mind searches and eddies

through the concourse of the terminal

with its way stations and concessions

of bottled water sandwiches,

dot.com billboards trumpeting instant riches,

another gourmet coffee at the cappuccino bar,

grande decaf half-skim latte,

seeking to delimit its appetites and hungers,

as even Money magazine wonders

how much is enough?

like one returned home after years of hard travel

I call out in greeting to my familiars—

Avarice, trusted and faithful retainer,

Extravagance, mi compeñaro,

Greed, my old friend, my bodyguard, my brother.

by Campbell McGrath

from Nouns & Verbs

Harper Collins, 2019

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie on Barack Obama’s ‘A Promised Land’

From The New York Times:

Barack Obama is as fine a writer as they come. It is not merely that this book avoids being ponderous, as might be expected, even forgiven, of a hefty memoir, but that it is nearly always pleasurable to read, sentence by sentence, the prose gorgeous in places, the detail granular and vivid. From Southeast Asia to a forgotten school in South Carolina, he evokes the sense of place with a light but sure hand. This is the first of two volumes, and it starts early in his life, charting his initial political campaigns, and ends with a meeting in Kentucky where he is introduced to the SEAL team involved in the Abbottabad raid that killed Osama bin Laden.

Barack Obama is as fine a writer as they come. It is not merely that this book avoids being ponderous, as might be expected, even forgiven, of a hefty memoir, but that it is nearly always pleasurable to read, sentence by sentence, the prose gorgeous in places, the detail granular and vivid. From Southeast Asia to a forgotten school in South Carolina, he evokes the sense of place with a light but sure hand. This is the first of two volumes, and it starts early in his life, charting his initial political campaigns, and ends with a meeting in Kentucky where he is introduced to the SEAL team involved in the Abbottabad raid that killed Osama bin Laden.

His focus is more political than personal, but when he does write about his family it is with a beauty close to nostalgia. Wriggling Malia into her first ballet tights. Baby Sasha’s laugh as he nibbles her feet. Michelle’s breath slowing as she falls asleep against his shoulder. His mother sucking ice cubes, her glands destroyed by cancer. The narrative is rooted in a storytelling tradition, with the accompanying tropes, as with the depiction of a staffer in his campaign for the Illinois State Senate, “taking a drag from her cigarette and blowing a thin plume of smoke to the ceiling.” The dramatic tension in the story of his gate-crashing, with Hillary Clinton by his side, to force a meeting with China at a climate summit is as enjoyable as noir fiction; no wonder his personal aide Reggie Love tells him afterward that it was some “gangster shit.” His language is unafraid of its own imaginative richness. He is given a cross by a nun with a face as “grooved as a peach pit.” The White House groundskeepers are “the quiet priests of a good and solemn order.” He questions whether his is a “blind ambition wrapped in the gauzy language of service.” There is a romanticism, a current of almost-melancholy in his literary vision. In Oslo, he looks outside to see a crowd of people holding candles, the flames flickering in the dark night, and one senses that this moves him more than the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony itself.

And what of that Nobel? He is incredulous when he hears he has been awarded the prize.

More here.

There Are Places in the World Where Rules Are Less Important Than Kindness

Andrew Anthony in The Guardian:

We live in a golden age of science writing, where weighty subjects such as quantum mechanics, genetics and cell theory are routinely rendered intelligible to mass audiences. Nonetheless, it remains rare for even the most talented science writers to fuse their work with a deep knowledge of the arts. One such rarity is the Italian theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli who, like some intellectual throwback to antiquity, treats the sciences and the humanities as complementary areas of knowledge and is a subtle interpreter of both. His best-known work is Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, which was a bestseller, most notably in Italy, where he is also well known for his erudite articles in newspapers such as Corriere della Sera.

We live in a golden age of science writing, where weighty subjects such as quantum mechanics, genetics and cell theory are routinely rendered intelligible to mass audiences. Nonetheless, it remains rare for even the most talented science writers to fuse their work with a deep knowledge of the arts. One such rarity is the Italian theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli who, like some intellectual throwback to antiquity, treats the sciences and the humanities as complementary areas of knowledge and is a subtle interpreter of both. His best-known work is Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, which was a bestseller, most notably in Italy, where he is also well known for his erudite articles in newspapers such as Corriere della Sera.

He writes on subjects as varied as classical philosophy, the meaning of science, the role of religion, the nature of black holes and the sociopolitical revelation of reading Hitler’s Mein Kampf (fascism grows from fear, not strength). His new book is a collection of his newspaper articles, a series of finely wrought essays that draw on an impressive hinterland of cultural and scientific learning. There is, for example, a fascinating exploration of Dante’s understanding of the shape of the cosmos, which, says Rovelli, anticipated Einstein’s brilliant intuition of a “three sphere” universe by six centuries. And a rather moving meditation on the nature of an octopus’s consciousness that could make even the most devoted pescatarian hesitate before ordering a dish made from our shockingly underrated eight-limbed friends.

More here.

Thursday, November 12, 2020

The Trumper with a Thousand Faces

Mark Oprea in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

ON JULY 21, 2016, the Republican National Convention was in full swing and delegates in ruddy Americana and cowboy attire packed the Cleveland’s Quicken Loans Arena. Although it’s hard for most of us to recall, this was a time where even staunch Republicans were doubting Trump’s ascendency to the United States’s highest office. I was there, and remember it fondly, and was intrigued as to why those who did want Trump were willing to vote for a man who had called Mexicans rapists and had made fun of a handicapped New York Times journalist. A 52-year-old delegate from Vermont stressed the usual three prongs: the border, anti-terrorism, the military. Trump’s insensitivity mattered not. “To me,” the delegate said, “if you’re not safe, then you’ve got nothing.”

ON JULY 21, 2016, the Republican National Convention was in full swing and delegates in ruddy Americana and cowboy attire packed the Cleveland’s Quicken Loans Arena. Although it’s hard for most of us to recall, this was a time where even staunch Republicans were doubting Trump’s ascendency to the United States’s highest office. I was there, and remember it fondly, and was intrigued as to why those who did want Trump were willing to vote for a man who had called Mexicans rapists and had made fun of a handicapped New York Times journalist. A 52-year-old delegate from Vermont stressed the usual three prongs: the border, anti-terrorism, the military. Trump’s insensitivity mattered not. “To me,” the delegate said, “if you’re not safe, then you’ve got nothing.”

The same search for the soul of the average Trump diehard is found in John Hibbing’s The Securitarian Personality, a 304-page-long petri dish observation of the brain matter that lies tucked in the belts of MAGA hats. Using Theodor Adorno’s The Authoritarian Personality as its theoretical base, Hibbing delves into the various facets of personality, demographics, behavior, and mindset that compose both devoted and on-the-fence Trump supporters and their conservative cousins, while tip-toeing across the tightrope strung between right-leaning sympathy and “racist” accusation.

More here.

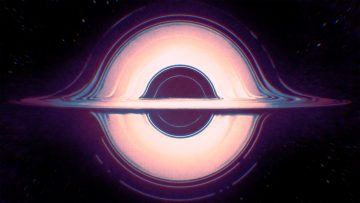

The Most Famous Paradox in Physics Nears Its End

George Musser in Quanta:

In a series of breakthrough papers, theoretical physicists have come tantalizingly close to resolving the black hole information paradox that has entranced and bedeviled them for nearly 50 years. Information, they now say with confidence, does escape a black hole. If you jump into one, you will not be gone for good. Particle by particle, the information needed to reconstitute your body will reemerge. Most physicists have long assumed it would; that was the upshot of string theory, their leading candidate for a unified theory of nature. But the new calculations, though inspired by string theory, stand on their own, with nary a string in sight. Information gets out through the workings of gravity itself — just ordinary gravity with a single layer of quantum effects.

In a series of breakthrough papers, theoretical physicists have come tantalizingly close to resolving the black hole information paradox that has entranced and bedeviled them for nearly 50 years. Information, they now say with confidence, does escape a black hole. If you jump into one, you will not be gone for good. Particle by particle, the information needed to reconstitute your body will reemerge. Most physicists have long assumed it would; that was the upshot of string theory, their leading candidate for a unified theory of nature. But the new calculations, though inspired by string theory, stand on their own, with nary a string in sight. Information gets out through the workings of gravity itself — just ordinary gravity with a single layer of quantum effects.

This is a peculiar role reversal for gravity. According to Einstein’s general theory of relativity, the gravity of a black hole is so intense that nothing can escape it. The more sophisticated understanding of black holes developed by Stephen Hawking and his colleagues in the 1970s did not question this principle. Hawking and others sought to describe matter in and around black holes using quantum theory, but they continued to describe gravity using Einstein’s classical theory — a hybrid approach that physicists call “semiclassical.” Although the approach predicted new effects at the perimeter of the hole, the interior remained strictly sealed off. Physicists figured that Hawking had nailed the semiclassical calculation. Any further progress would have to treat gravity, too, as quantum.

That is what the authors of the new studies dispute.

More here.

Why the American Press Keeps Getting Terror in France Wrong

Caroline Fourest in Tablet:

Five years ago, American journalists called me following the terrorist attack that took the lives of my former colleagues and friends at Charlie Hebdo. They all thought that we were going to elect Marine Le Pen. I tried to explain to them that it’s precisely because there is a leftist movement associated with Charlie—both anti-racist and secular, a left that remains lucid about the dangers of extremism—that we had a chance to avoid that fate. But my explanations were in vain.

Five years ago, American journalists called me following the terrorist attack that took the lives of my former colleagues and friends at Charlie Hebdo. They all thought that we were going to elect Marine Le Pen. I tried to explain to them that it’s precisely because there is a leftist movement associated with Charlie—both anti-racist and secular, a left that remains lucid about the dangers of extremism—that we had a chance to avoid that fate. But my explanations were in vain.

A few years later, America elected Donald Trump, who dared make equivalences between anti-racists and neo-Nazis in Charlottesville, fanned nostalgia for white supremacy, declared a Muslim ban, and in addition wanted to “grab [women] by the pussy,” and showed open contempt for the truth and democracy. How could such a great democracy have elected this man? It’s a question that has troubled us for four years in France.

Yet after the Charlie attacks, we understood what was pushing certain Americans, many of whom were perfectly aware of Trump’s faults and incompetence, to vote for him—even as we hoped for better. All we had to do was read The New York Times, The Washington Post, the Financial Times, Bloomberg, and the CNN website to see their coverage of the terror attacks in France, and it became clear that a sector of the American elite was no more attached to truth than Trump was.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s “Biggest Ideas in the Universe” video series: Introduction, and First Video on Conservation

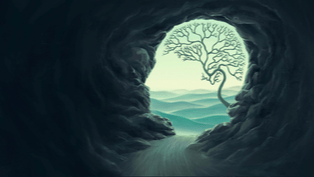

Are We Wired to Be Outside?

Grigori Guitchounts in Nautilus:

The evolutionary explanation for human connection to nature is a colossal safari through the African savanna, where our ancestors fought, fed, and frolicked for millions of years. The biologist E.O. Wilson speculated on this story in Biophilia, a slim volume on human attraction to nature. Wilson defined biophilia as an “innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes.” He argued that if other animals are adapted to their environments and are best-suited to the environments in which they evolved—for example, a thick white coat serves the polar bear well in its native cold and snowy Arctic—then is it possible that humans too, despite our ability to live anywhere on this planet, are best adapted to the particular environment in which we evolved?

The evolutionary explanation for human connection to nature is a colossal safari through the African savanna, where our ancestors fought, fed, and frolicked for millions of years. The biologist E.O. Wilson speculated on this story in Biophilia, a slim volume on human attraction to nature. Wilson defined biophilia as an “innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes.” He argued that if other animals are adapted to their environments and are best-suited to the environments in which they evolved—for example, a thick white coat serves the polar bear well in its native cold and snowy Arctic—then is it possible that humans too, despite our ability to live anywhere on this planet, are best adapted to the particular environment in which we evolved?

“The more habitats I have explored, the more I have felt that certain common features subliminally attract and hold my attention,” Wilson wrote. “Is it unreasonable to suppose that the human mind is primed to respond most strongly to some narrowly defined qualities that had the greatest impact on survival in the past?” Those qualities include the savanna’s sprawling grasslands, sparse trees, cliffs and other vantage points, as well as bodies of water, which provided resources. Wilson cited human tendencies to build savanna-like environments where they are not found naturally, as in malls or gardens; open-concept architecture seems to have hit on our love of vast spaces, too.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Sunlight

I’m utterly helpless.

I’ll just have to swallow my spit

and adversity, too.

But look!

A distinguished visitor deigns to visit

my tiny, north-facing cell.

Not the chief making his rounds, no.

As evening falls, a ray of sunlight.

A gleam no bigger than a crumpled postage stamp.

I’m crazy about it! Real first love!

I try to get it to settle on the palm of my hand,

to warm the toes of my shyly bared foot.

Then as I kneel and offer it my undevout, lean face,

in a moment that scrap of sunlight slips away.

After the guest has departed through the bars

the room feels several times colder and darker.

This special cell of a military prison

is like a photographer’s darkroom.

Without any sunlight I laughed like a fool.

One day it was a coffin holding a corpse.

One day it was altogether the sea. How wonderful!

A few people survive here.

Being alive is a sea

without a single sail in sight.

by Ko Un

from Songs for Tomorrow

Green Integer Books, 2009

Of Beauty and Consolation: Martha Nussbaum

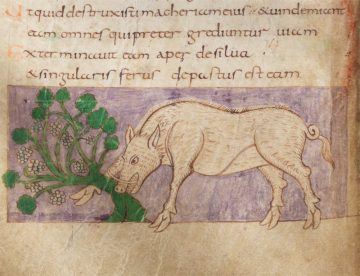

Ubiquitous Medieval Pigs

Jamie Kreiner at Lapham’s Quarterly:

These are ancient texts, but the pig’s characterization as a ravenous and dirty animal has transcended particular historical moments. Christians in early medieval Europe made the same associations, and so do we. More than one historian has pointed this out over the years, partly with the goal of rehabilitating the animals’ reputation. But this flat stereotype, this singular beast, was not the only profile a pig could have, even in the past: “premodern” views were subtler than the shorthand symbolism suggests. In late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, farmers, policy makers, and philosophers were perfectly capable of holding multiple views of pigs simultaneously, of playing into a familiar caricature but also of honing in on the complexities of the species. They saw that pigs were not merely commodities that provided humans with meat or symbols that worked as handy metaphors. They were also creatures that were capable of adapting to and altering their environments, including the human environments that only partially constrained them. Pigs were difficult to fully domesticate, both physically and conceptually. They called attention to themselves and required some engagement with their complex lives.

These are ancient texts, but the pig’s characterization as a ravenous and dirty animal has transcended particular historical moments. Christians in early medieval Europe made the same associations, and so do we. More than one historian has pointed this out over the years, partly with the goal of rehabilitating the animals’ reputation. But this flat stereotype, this singular beast, was not the only profile a pig could have, even in the past: “premodern” views were subtler than the shorthand symbolism suggests. In late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, farmers, policy makers, and philosophers were perfectly capable of holding multiple views of pigs simultaneously, of playing into a familiar caricature but also of honing in on the complexities of the species. They saw that pigs were not merely commodities that provided humans with meat or symbols that worked as handy metaphors. They were also creatures that were capable of adapting to and altering their environments, including the human environments that only partially constrained them. Pigs were difficult to fully domesticate, both physically and conceptually. They called attention to themselves and required some engagement with their complex lives.

more here.

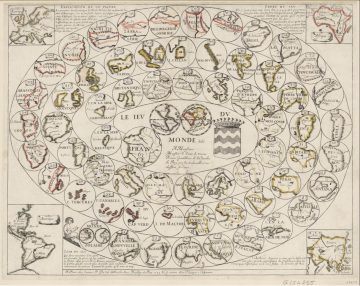

The Rise of The Cartographic Board Game

Colton Valentine at Cabinet:

In 1795, Henry Carington Bowles released Bowles’s European Geographical Amusement, or Game of Geography, the latest in his family’s board game series. Allegedly based on a 1749 travelogue, “the Grand Tour of Europe, by Dr. Nugent,” it combined learned pretensions with simple rules. “Having agreed to make an elegant and instructive TOUR of EUROPE,” players took turns rolling an eight-sided “Totum” and moving their “Pillars” through the appropriate number of cities. Whoever returned to London first was “entitled to the applause of the company and honor of being esteemed the best instructed and speediest traveler”: an enviable but deceptive accolade. In fact, erudition and swiftness were inversely correlated in Bowles’s game; being “instructed” required that your Pillar be delayed.

In 1795, Henry Carington Bowles released Bowles’s European Geographical Amusement, or Game of Geography, the latest in his family’s board game series. Allegedly based on a 1749 travelogue, “the Grand Tour of Europe, by Dr. Nugent,” it combined learned pretensions with simple rules. “Having agreed to make an elegant and instructive TOUR of EUROPE,” players took turns rolling an eight-sided “Totum” and moving their “Pillars” through the appropriate number of cities. Whoever returned to London first was “entitled to the applause of the company and honor of being esteemed the best instructed and speediest traveler”: an enviable but deceptive accolade. In fact, erudition and swiftness were inversely correlated in Bowles’s game; being “instructed” required that your Pillar be delayed.

more here.

Wednesday, November 11, 2020

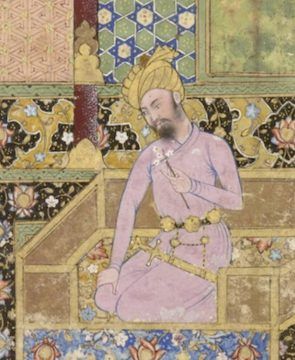

The First Mughal Emperor’s Towering Account of Exile, Bloody Conquest, and the Natural World

William Dalrymple at Literary Hub:

At the end of 1525, Zahiru’d-din Muhammad Babur, a Timurid poet-prince from Farghana in Central Asia, descended the Khyber Pass with a small army of hand-picked followers; with him he brought some of the first modern muskets and cannons seen in India. With these he defeated the Delhi Sultan, Ibrahim Lodhi, and established his garden-capital at Agra.

At the end of 1525, Zahiru’d-din Muhammad Babur, a Timurid poet-prince from Farghana in Central Asia, descended the Khyber Pass with a small army of hand-picked followers; with him he brought some of the first modern muskets and cannons seen in India. With these he defeated the Delhi Sultan, Ibrahim Lodhi, and established his garden-capital at Agra.

This was not Babur’s first conquest. He had spent much of his youth throneless, living with his companions from day to day, rustling sheep and stealing food. Occasionally he would capture a town—he was 14 when he first took Samarkand and held it for four months. Aged 21, he finally managed to seize and secure Kabul, and it was this Afghan base that became the springboard for his later conquest of India.

But before this he had lived for years in a tent, displaced and dispossessed, a peripatetic existence that had little appeal to him. “It passed through my mind,” he wrote, “that to wander from mountain to mountain, homeless and houseless . . . had nothing to recommend it.”

More here.

The Husband-and-Wife Team Behind the Leading COVID-19 Vaccine

David Gelles in the New York Times:

BioNTech began work on the vaccine in January, after Dr. Sahin read an article in the medical journal The Lancet that left him convinced that the coronavirus, at the time spreading quickly in parts of China, would explode into a full-blown pandemic. Scientists at the company, based in Mainz, Germany, canceled vacations and set to work on what they called Project Lightspeed.

BioNTech began work on the vaccine in January, after Dr. Sahin read an article in the medical journal The Lancet that left him convinced that the coronavirus, at the time spreading quickly in parts of China, would explode into a full-blown pandemic. Scientists at the company, based in Mainz, Germany, canceled vacations and set to work on what they called Project Lightspeed.

“There are not too many companies on the planet which have the capacity and the competence to do it so fast as we can do it,” Dr. Sahin said in an interview last month. “So it felt not like an opportunity, but a duty to do it, because I realized we could be among the first coming up with a vaccine.”

After BioNTech had identified several promising vaccine candidates, Dr. Sahin concluded that the company would need help to rapidly test them, win approval from regulators and bring the best candidate to market. BioNTech and Pfizer had been working together on a flu vaccine since 2018, and in March, they agreed to collaborate on a coronavirus vaccine.

More here.

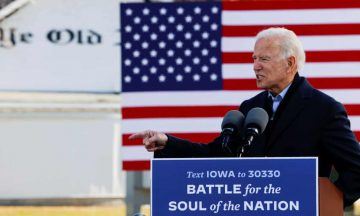

Biden may pave the way for a more competent autocrat

George Monbiot in The Guardian:

Obama’s attempt to reconcile irreconcilable forces, to paper over the chasms, arguably gave Donald Trump his opening. Rather than confronting the banks whose reckless greed had caused the financial crisis, he allowed his Treasury secretary, Timothy Geithner, to “foam the runway” for them by allowing 10 million families to lose their homes. His justice department and the attorney general blocked efforts to pursue apparent wrongdoing by the financiers. He pressed for trade agreements that would erode workers’ rights and environmental standards, and presided over the widening of inequality and the concentration of wealth, casualisation of labour and record mergers and acquisitions. In other words, he failed to break the consensus that had grown around the dominant ideology of our times: neoliberalism.

Obama’s attempt to reconcile irreconcilable forces, to paper over the chasms, arguably gave Donald Trump his opening. Rather than confronting the banks whose reckless greed had caused the financial crisis, he allowed his Treasury secretary, Timothy Geithner, to “foam the runway” for them by allowing 10 million families to lose their homes. His justice department and the attorney general blocked efforts to pursue apparent wrongdoing by the financiers. He pressed for trade agreements that would erode workers’ rights and environmental standards, and presided over the widening of inequality and the concentration of wealth, casualisation of labour and record mergers and acquisitions. In other words, he failed to break the consensus that had grown around the dominant ideology of our times: neoliberalism.

More here.