Corey Robin in The New Yorker:

Corey Robin in The New Yorker:

he professor and the politician are a dyad of perpetual myth. In one myth, they are locked in conflict, sparring over the claims of reason and the imperative of power. Think Socrates and Athens, or Noam Chomsky and the American state. In another myth, they are reconciled, even fused. The professor becomes a politician, saving the polity from corruption and ignorance, demagoguery and vice. Think Plato’s philosopher-king, or Aaron Sorkin’s Jed Bartlet. The nobility of ideas is preserved, and transmuted, slowly, into the stuff of action.

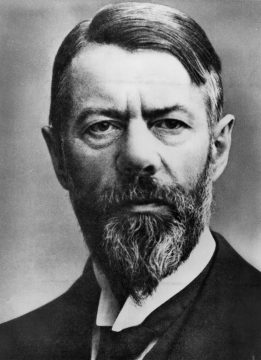

The sociologist Max Weber spent much of his life seduced by this second fable. A scholar of hot temper and volcanic energy, Weber longed to be a politician of cold focus and hard reason. Across three decades of a scholarly career, in Wilhelmine and Weimar Germany, he made repeated and often failed incursions into the public sphere—to give advice, stand for office, form a party, negotiate a treaty, and write a constitution. His “secret love,” he confessed to a friend, was “the political.” Even in the delirium of his final days, he could be heard declaiming on behalf of the German people, jousting with their enemies in several of the many languages he knew. “If one is lucky” in politics, he observed, a “genius appears just once every few hundred years.” That left the door wide open for him.

More here. And see also Patrick Thaddeus Jackson’s response over at Lawyers, Guns and Money:

1) The whole point of Weber’s “vocation” lectures was to caution his listeners against either a political or an academic “savior.” In the lecture on Wissenschaft — usually translated “science,” but the sense of the word in German is more like “systematic scholarship” — Weber takes pains to argue that other than “some overgrown children in their professorial chairs or editorial offices,” no one thinks that academic study can teach us anything about the meaning of the world. And in the lecture on politics, Weber is, if anything, more afraid of the revolutionary prophet taking over the reins of government than he is of the amoral cynic who treats politics as a means for personal enrichment:

“…people who have just preached ‘love against force’ are found calling for the use of force the very next moment. It is always the very last use of force that will then bring about a situation in which all violence will have been destroyed — just as our military leaders tell the soldiers that every offensive will be the last. This one will bring victory and then peace. The man who embraces an ethics of conviction is unable to tolerate the ethical irrationality of the world.”

More here.