Kevin Mitchell in Wiring the Brain:

It seems an innocent enough question: why are males more frequently left-handed than females? But the answer is far from simple, and it reveals fundamental principles of how our psychological and behavioural traits are encoded in our genomes, how variability in those traits arise, and how development is channelled towards specific outcomes. It turns out that the explanation rests on an underlying difference between males and females that has far-reaching consequences for all kinds of traits, including neurodevelopmental disorders.

It seems an innocent enough question: why are males more frequently left-handed than females? But the answer is far from simple, and it reveals fundamental principles of how our psychological and behavioural traits are encoded in our genomes, how variability in those traits arise, and how development is channelled towards specific outcomes. It turns out that the explanation rests on an underlying difference between males and females that has far-reaching consequences for all kinds of traits, including neurodevelopmental disorders.

A recent tweet from Abdel Abdellaoui showed data on rates of left-handedness obtained from the UK Biobank, and asked two questions: why is left-handedness more common in males and why are rates of reported left-handedness increasing over time?

I don’t think the answer to the second question is known but I presume it has to do with the declining practice of forcing left-handers to write right-handed. This once common practice reflects a long history of prejudice against lefties, illustrated by the derivation of the word “sinister”, which in Latin means “left”, as opposed to “dexter” meaning “right” which is the root of the positive words “dexterity” and “dextrous”.

The first question – why is left-handedness more common in males? – is the one I want to explore here, as it opens up some fascinating questions about robustness, variability, and developmental attractors.

More here.

For those awash in anxiety and alienation, who feel that everything is spinning out of control, conspiracy theories are extremely effective emotional tools. For those in low status groups, they provide a sense of superiority: I possess important information most people do not have. For those who feel powerless, they provide agency: I have the power to reject “experts” and expose hidden cabals. As Cass Sunstein of Harvard Law School points out, they provide liberation: If I imagine my foes are completely malevolent, then I can use any tactic I want.

For those awash in anxiety and alienation, who feel that everything is spinning out of control, conspiracy theories are extremely effective emotional tools. For those in low status groups, they provide a sense of superiority: I possess important information most people do not have. For those who feel powerless, they provide agency: I have the power to reject “experts” and expose hidden cabals. As Cass Sunstein of Harvard Law School points out, they provide liberation: If I imagine my foes are completely malevolent, then I can use any tactic I want. “God,” a friend of mine recently confided to me, “needs to make a comeback.”

“God,” a friend of mine recently confided to me, “needs to make a comeback.” Wales mattered to Jan. In midlife, and at more or less the same time as her gender reassignment, she embraced what she called Welsh Republicanism. Her home, Trefan Morys, is in a remote area near the town of Criccieth. You leave the main road, take a long, rutted drive, negotiate the narrow entrance in a high stone wall, and you are suddenly in an enchanted space. Elizabeth was the architect of the garden and Jan the interior designer. You enter the house through a two-part stable door (Jan always greeting you with the words, “Not today, thank you”), into a cozy kitchen, and then the main downstairs room. The walls are lined with eight thousand books, including specially leather-bound editions of Jan’s own. Up the stairs there is another long room, with an old-fashioned stove in the middle. Here are more books, but this space is given over mainly to memorabilia and paintings. Pride of place is given to a six-foot-long painting of Venice, done by Jan, in which every detail of the miraculous city is rendered (including tiny portraits of the two eldest sons, who were very young at the time Jan painted it). Model ships hang from the ceiling, and paintings of ships adorn the walls. Jan loved ships from the time she spied them, as a child, through a telescope as they passed through the Bristol Channel near her family’s home.

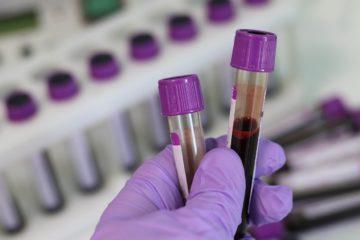

Wales mattered to Jan. In midlife, and at more or less the same time as her gender reassignment, she embraced what she called Welsh Republicanism. Her home, Trefan Morys, is in a remote area near the town of Criccieth. You leave the main road, take a long, rutted drive, negotiate the narrow entrance in a high stone wall, and you are suddenly in an enchanted space. Elizabeth was the architect of the garden and Jan the interior designer. You enter the house through a two-part stable door (Jan always greeting you with the words, “Not today, thank you”), into a cozy kitchen, and then the main downstairs room. The walls are lined with eight thousand books, including specially leather-bound editions of Jan’s own. Up the stairs there is another long room, with an old-fashioned stove in the middle. Here are more books, but this space is given over mainly to memorabilia and paintings. Pride of place is given to a six-foot-long painting of Venice, done by Jan, in which every detail of the miraculous city is rendered (including tiny portraits of the two eldest sons, who were very young at the time Jan painted it). Model ships hang from the ceiling, and paintings of ships adorn the walls. Jan loved ships from the time she spied them, as a child, through a telescope as they passed through the Bristol Channel near her family’s home. The UK National Health Service (NHS) is set to initiate the trial of Galleri blood test that can potentially detect over 50 types of cancers. Developed by GRAIL, the test is capable of detecting early-stage cancers through a simple blood test. In research on patients with cancer signs, the test identified many types like head and neck, ovarian, pancreatic, oesophageal and some blood cancers, which are difficult to diagnose early. The blood test checks for molecular changes. NHS Chief Executive Simon Stevens said: “Early detection – particularly for hard-to-treat conditions like ovarian and pancreatic cancer – has the potential to save many lives. “This promising blood test could therefore be a game-changer in cancer care, helping thousands of more people to get successful treatment.” Anticipated to start in the middle of next year, the GRAIL pilot will involve 165,000 people. This participant population will include 140,000 people aged 50 to 79 years who have no symptoms but will have annual blood tests for three years.

The UK National Health Service (NHS) is set to initiate the trial of Galleri blood test that can potentially detect over 50 types of cancers. Developed by GRAIL, the test is capable of detecting early-stage cancers through a simple blood test. In research on patients with cancer signs, the test identified many types like head and neck, ovarian, pancreatic, oesophageal and some blood cancers, which are difficult to diagnose early. The blood test checks for molecular changes. NHS Chief Executive Simon Stevens said: “Early detection – particularly for hard-to-treat conditions like ovarian and pancreatic cancer – has the potential to save many lives. “This promising blood test could therefore be a game-changer in cancer care, helping thousands of more people to get successful treatment.” Anticipated to start in the middle of next year, the GRAIL pilot will involve 165,000 people. This participant population will include 140,000 people aged 50 to 79 years who have no symptoms but will have annual blood tests for three years. For centuries people have pondered the

For centuries people have pondered the  You might recall the strange case of Matthew J. Mayhew, professor of educational administration at The Ohio State University. In late September he published

You might recall the strange case of Matthew J. Mayhew, professor of educational administration at The Ohio State University. In late September he published  At the heart of Oxford’s effort to produce a Covid vaccine are half a dozen scientists who between them brought decades of experience to the challenge of designing, developing, manufacturing and trialling a

At the heart of Oxford’s effort to produce a Covid vaccine are half a dozen scientists who between them brought decades of experience to the challenge of designing, developing, manufacturing and trialling a  “AND WHAT ABOUT unbiased research? What about pure knowledge?” bursts out the more idealistic of the two debaters. Before the other, the more cynical one, even has a chance to answer, the idealist ambushes him with even grander questions: “What about the truth, my dear sir, which is so intimately bound up with freedom, and its martyrs?” We can picture the caustic smile on the cynic’s face. “My good friend,” the cynic answers, “there is no such thing as pure knowledge.” His words come out calmly, fully formed, in sharp contrast to the idealist’s passionate, if sometimes logically disjointed pronouncements. The cynic’s rebuttal is merciless:

“AND WHAT ABOUT unbiased research? What about pure knowledge?” bursts out the more idealistic of the two debaters. Before the other, the more cynical one, even has a chance to answer, the idealist ambushes him with even grander questions: “What about the truth, my dear sir, which is so intimately bound up with freedom, and its martyrs?” We can picture the caustic smile on the cynic’s face. “My good friend,” the cynic answers, “there is no such thing as pure knowledge.” His words come out calmly, fully formed, in sharp contrast to the idealist’s passionate, if sometimes logically disjointed pronouncements. The cynic’s rebuttal is merciless: Our quest centres on this simple question: why do so many languages and cultures identify these North American natives as “the birds from India” (oiseaux d’Inde, or simply dinde in French).

Our quest centres on this simple question: why do so many languages and cultures identify these North American natives as “the birds from India” (oiseaux d’Inde, or simply dinde in French). Truth is, this year has seen plenty of gratitude, instinctively and generously expressed. The people applauding out their windows for emergency responders, the heart signs, the food deliveries to essential workers, the neighborhood trash teams, the looking-in on elders. Online platforms as purpose-built as gratefulness.org and as customarily combative as Twitter have been flooded with counted blessings: for our loved ones, for the Amazon carrier, for our dogs. People gave thanks for simple things, mostly – their families, video chats, the “tall green trees that are older than me,” a hummingbird, the ocean, soup. (“Yep, soup,” says a West Sacramento, California, man.) But many, many other expressions of gratitude took the form of generosity, of trying to give back or pay it forward. The news was filled with stories of people in grocery lines paying for the customer coming next, donations to farmworkers, businesses furnishing free meals to front-line responders.

Truth is, this year has seen plenty of gratitude, instinctively and generously expressed. The people applauding out their windows for emergency responders, the heart signs, the food deliveries to essential workers, the neighborhood trash teams, the looking-in on elders. Online platforms as purpose-built as gratefulness.org and as customarily combative as Twitter have been flooded with counted blessings: for our loved ones, for the Amazon carrier, for our dogs. People gave thanks for simple things, mostly – their families, video chats, the “tall green trees that are older than me,” a hummingbird, the ocean, soup. (“Yep, soup,” says a West Sacramento, California, man.) But many, many other expressions of gratitude took the form of generosity, of trying to give back or pay it forward. The news was filled with stories of people in grocery lines paying for the customer coming next, donations to farmworkers, businesses furnishing free meals to front-line responders. Mark Ellison stood on the raw plywood floor, staring up into the gutted nineteenth-century town house. Above him, joists, beams, and electrical conduits crisscrossed in the half-light like a demented spider’s web. He still wasn’t sure how to build this thing. According to the architect’s plans, this room was to be the master bath—a cocoon of curving plaster shimmering with pinprick lights. But the ceiling made no sense. One half of it was a barrel vault, like the inside of a Roman basilica; the other half was a groin vault, like the nave of a cathedral. On paper, the rounded curves of one vault flowed smoothly into the elliptical curves of the other. But getting them to do so in three dimensions was a nightmare. “I showed the drawings to the bass player in my band,” Ellison said. “He’s a physicist, so I asked him, ‘Could you do the calculus for this?’ He said, ‘No.’ ”

Mark Ellison stood on the raw plywood floor, staring up into the gutted nineteenth-century town house. Above him, joists, beams, and electrical conduits crisscrossed in the half-light like a demented spider’s web. He still wasn’t sure how to build this thing. According to the architect’s plans, this room was to be the master bath—a cocoon of curving plaster shimmering with pinprick lights. But the ceiling made no sense. One half of it was a barrel vault, like the inside of a Roman basilica; the other half was a groin vault, like the nave of a cathedral. On paper, the rounded curves of one vault flowed smoothly into the elliptical curves of the other. But getting them to do so in three dimensions was a nightmare. “I showed the drawings to the bass player in my band,” Ellison said. “He’s a physicist, so I asked him, ‘Could you do the calculus for this?’ He said, ‘No.’ ” He called the next day. We went out for lunch. We went out for dinner. We went out for drinks. We went out for dinner again. We went out for drinks again. We went out for dinner and drinks again. We went out for dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and

He called the next day. We went out for lunch. We went out for dinner. We went out for drinks. We went out for dinner again. We went out for drinks again. We went out for dinner and drinks again. We went out for dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and dinner and drinks and Conspiracy theories come in all shapes and sizes, but perhaps the most common form is the Global Cabal theory. A

Conspiracy theories come in all shapes and sizes, but perhaps the most common form is the Global Cabal theory. A  On a mild autumn day in 2016, the Hungarian mathematician

On a mild autumn day in 2016, the Hungarian mathematician