The Golden Deer

Could you ever imagine

a country as beautiful,

a wilderness lovelier than this?

In its soil are the roots

of a forest, Dandakaranya –

dream-green, dream-dark.

Its silence braided by the music

in the silver-blond plaits

of virgin waterfalls.

There a demon from Serendip,

disguised as a golden stag

darts in and out

of the corners of your eyes.

A fleeting flash of glitter,

which steals away

what desire cannot attain.

Elusive as the wind,

fleeing with the sunshine

it leads you away from yourself,

the more you chase it

through foliage and undergrowth.

It is still said

that if you see the golden deer

even once,

you are condemned to seek it

for the rest of your life

and never find it,

though you may catch

glimpses of it, now and then.

A fleeting flash of glitter,

antlers of gold

that snare the sun.

by Srinjay Chakravarti

from The National Poetry Library

The manufacture of many chemicals important to human health and comfort consumes fossil fuels, thereby contributing to extractive processes, carbon dioxide emissions and climate change. A new approach employs sunlight to convert waste carbon dioxide into these needed chemicals, potentially reducing emissions in two ways: by using the unwanted gas as a raw material and sunlight, not fossil fuels, as the source of energy needed for production. This process is becoming increasingly feasible thanks to advances in sunlight-activated catalysts, or photocatalysts. In recent years investigators have developed photocatalysts that break the resistant double bond between carbon and oxygen in carbon dioxide. This is a critical first step in creating “solar” refineries that produce useful compounds from the waste gas—including “platform” molecules that can serve as raw materials for the synthesis of such varied products as medicines, detergents, fertilizers and textiles.

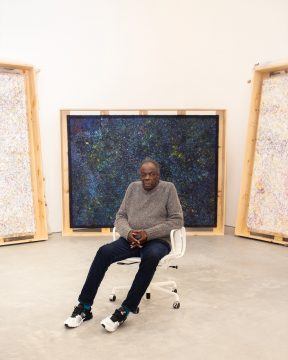

The manufacture of many chemicals important to human health and comfort consumes fossil fuels, thereby contributing to extractive processes, carbon dioxide emissions and climate change. A new approach employs sunlight to convert waste carbon dioxide into these needed chemicals, potentially reducing emissions in two ways: by using the unwanted gas as a raw material and sunlight, not fossil fuels, as the source of energy needed for production. This process is becoming increasingly feasible thanks to advances in sunlight-activated catalysts, or photocatalysts. In recent years investigators have developed photocatalysts that break the resistant double bond between carbon and oxygen in carbon dioxide. This is a critical first step in creating “solar” refineries that produce useful compounds from the waste gas—including “platform” molecules that can serve as raw materials for the synthesis of such varied products as medicines, detergents, fertilizers and textiles. The show’s main news is in sculpture: there are several small pyramids and one immense one, all raised slightly off the floor and built of innumerable horizontal sheets of laminated plywood with regularly spaced bands of aluminum. Gorgeously dyed in sumptuous color—bringing out and celebrating the textures of the wood grain—the blunt structures radiate like light sources. Do they suggest late entries in the repertoire of Minimalism? They do, but with a sense of re-starting the aesthetic from scratch—getting it right, even, at long last. The pieces play a role in another of the show’s revelations: a series of large (up to twenty feet wide) neo- or post- or, let’s say, para-color-field paintings that owe the ruggedness of their paint surfaces to incorporations of leftover pyramid sawdust. Bevelled edges flirt with object-ness, making the works seem fat material presentations, protuberant from walls, rather than pictures. But, as always with Gilliam, paint wins. Thick grounds in white or black are crazed with specks, splotches, and occasional dragged strokes of varied color. While you feel the weight of the wooden supports, your gaze loses itself in something like starry skies: dizzying impressions of infinite distance in tension with the dense grounds, which are complicated by tiny bits of collaged and overpainted wooden squares. Registering the jittery chromatic harmonies and occasional underlying structures—ghosts of geometry—takes time. Seemingly decorative at first glance, the paintings turn inexhaustibly absorbing and exciting when contemplated. Like everything else in this show of an artist who is old in years, they feel defiantly brand spanking new.

The show’s main news is in sculpture: there are several small pyramids and one immense one, all raised slightly off the floor and built of innumerable horizontal sheets of laminated plywood with regularly spaced bands of aluminum. Gorgeously dyed in sumptuous color—bringing out and celebrating the textures of the wood grain—the blunt structures radiate like light sources. Do they suggest late entries in the repertoire of Minimalism? They do, but with a sense of re-starting the aesthetic from scratch—getting it right, even, at long last. The pieces play a role in another of the show’s revelations: a series of large (up to twenty feet wide) neo- or post- or, let’s say, para-color-field paintings that owe the ruggedness of their paint surfaces to incorporations of leftover pyramid sawdust. Bevelled edges flirt with object-ness, making the works seem fat material presentations, protuberant from walls, rather than pictures. But, as always with Gilliam, paint wins. Thick grounds in white or black are crazed with specks, splotches, and occasional dragged strokes of varied color. While you feel the weight of the wooden supports, your gaze loses itself in something like starry skies: dizzying impressions of infinite distance in tension with the dense grounds, which are complicated by tiny bits of collaged and overpainted wooden squares. Registering the jittery chromatic harmonies and occasional underlying structures—ghosts of geometry—takes time. Seemingly decorative at first glance, the paintings turn inexhaustibly absorbing and exciting when contemplated. Like everything else in this show of an artist who is old in years, they feel defiantly brand spanking new. The Moth and the Mountain is a strange book. Several times this past month I’ve told friends about it, describing its central figure, Maurice Wilson: war hero, heartbreaker, daydreamer, globetrotter, irrepressible adventurer, the man who, in 1932, dreamed up a scheme to fly the moth of the title (a de Havilland biplane) on to Mount Everest, before hopping out and shinning up to the summit. My wide-eyed friends would blink and ask, ‘And this is a real story?’ and I’d nod, and then they’d ask the terminal question, ‘What happened next?’

The Moth and the Mountain is a strange book. Several times this past month I’ve told friends about it, describing its central figure, Maurice Wilson: war hero, heartbreaker, daydreamer, globetrotter, irrepressible adventurer, the man who, in 1932, dreamed up a scheme to fly the moth of the title (a de Havilland biplane) on to Mount Everest, before hopping out and shinning up to the summit. My wide-eyed friends would blink and ask, ‘And this is a real story?’ and I’d nod, and then they’d ask the terminal question, ‘What happened next?’ Stacey Abrams is the former Georgia state house minority leader, whose fierce fight for Georgians’ right to vote has been credited for potentially handing the state to the Democrats for the first time in 28 years. But Abrams has another identity: the novelist Selena Montgomery, a romance and thriller writer who has sold more than 100,000 copies of her eight novels.

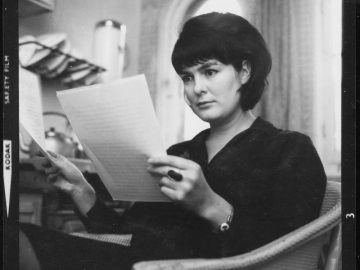

Stacey Abrams is the former Georgia state house minority leader, whose fierce fight for Georgians’ right to vote has been credited for potentially handing the state to the Democrats for the first time in 28 years. But Abrams has another identity: the novelist Selena Montgomery, a romance and thriller writer who has sold more than 100,000 copies of her eight novels. You didn’t need to know every note of Nirvana’s angst-rock classic “In Bloom” to marvel at the spectacle of a little girl drumming along to the song in perfect synchronization last November, her face scrawled over with joy and passion. The internet is an open playing field for regular people performing impressive feats, and over a couple of years,

You didn’t need to know every note of Nirvana’s angst-rock classic “In Bloom” to marvel at the spectacle of a little girl drumming along to the song in perfect synchronization last November, her face scrawled over with joy and passion. The internet is an open playing field for regular people performing impressive feats, and over a couple of years,  A few years ago, I was listening to a recording of the Tannhäuser overture on YouTube. Whether out of glazed torpor or instinctive masochism, I found myself scrolling down to read the comments.

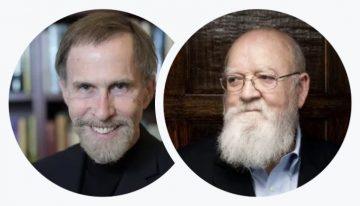

A few years ago, I was listening to a recording of the Tannhäuser overture on YouTube. Whether out of glazed torpor or instinctive masochism, I found myself scrolling down to read the comments. Imagine you were locked in a sealed room, with no way to access the outside world but a few screens showing a view of what’s outside. Seems scary and limited, but that’s essentially the situation that our brains find themselves in — locked in our skulls, with only the limited information from a few unreliable sensory modalities to tell them what’s going on inside. Neuroscientist David Eagleman has long been interested in how the brain processes that sensory input, and also how we might train it to learn completely new ways of accessing the outside world, with important ramifications for virtual reality and novel brain/computer interface techniques.

Imagine you were locked in a sealed room, with no way to access the outside world but a few screens showing a view of what’s outside. Seems scary and limited, but that’s essentially the situation that our brains find themselves in — locked in our skulls, with only the limited information from a few unreliable sensory modalities to tell them what’s going on inside. Neuroscientist David Eagleman has long been interested in how the brain processes that sensory input, and also how we might train it to learn completely new ways of accessing the outside world, with important ramifications for virtual reality and novel brain/computer interface techniques. The election of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris comes as an enormous relief. Our democracy has been saved from a second Trump term, and arguably saved as such. Yet the outcome falls short of expressing a clear rebuke of Trumpism. The GOP now has a choice: take the defeat to heart and rebrand, or double down on the Trumpist program.

The election of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris comes as an enormous relief. Our democracy has been saved from a second Trump term, and arguably saved as such. Yet the outcome falls short of expressing a clear rebuke of Trumpism. The GOP now has a choice: take the defeat to heart and rebrand, or double down on the Trumpist program. It works! Scientists have greeted with cautious optimism a press-release declaring positive interim results from a coronavirus vaccine trial — the first to report from the final, ‘phase III’ round of human testing. Drug company Pfizer’s announcement on 9 November offers the first compelling evidence that a vaccine can prevent COVID-19 — and bodes well for other COVID-19 vaccines in development. But the information released at this early stage does not answer key questions that will determine whether the Pfizer vaccine, and others like it, can prevent the most severe cases or quell the coronavirus pandemic. “We need to see the data in the end, but that still doesn’t dampen my enthusiasm. This is fantastic,” says Florian Krammer, a virologist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, who is also one of the trial’s more than 40,000 participants. “I hope I’m not in the placebo group.”

It works! Scientists have greeted with cautious optimism a press-release declaring positive interim results from a coronavirus vaccine trial — the first to report from the final, ‘phase III’ round of human testing. Drug company Pfizer’s announcement on 9 November offers the first compelling evidence that a vaccine can prevent COVID-19 — and bodes well for other COVID-19 vaccines in development. But the information released at this early stage does not answer key questions that will determine whether the Pfizer vaccine, and others like it, can prevent the most severe cases or quell the coronavirus pandemic. “We need to see the data in the end, but that still doesn’t dampen my enthusiasm. This is fantastic,” says Florian Krammer, a virologist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, who is also one of the trial’s more than 40,000 participants. “I hope I’m not in the placebo group.” Zamyatin is among the few gifted twentieth-century writers who responded to ideological tyranny by poetically integrating mathematical science into a philosophical anthropology. Dostoyevsky’s literary topographies of the soul are the

Zamyatin is among the few gifted twentieth-century writers who responded to ideological tyranny by poetically integrating mathematical science into a philosophical anthropology. Dostoyevsky’s literary topographies of the soul are the  Three is the second of the four brilliant and enigma-ridden novels that Ann Quin published before drowning off the coast of Brighton in 1973 at the age of thirty-seven. The mysterious character S—the absent protagonist or antiheroine hypotenuse of this love-triangle tale—dies in similar fashion … or perhaps she’s stabbed to death by a gang of nameless, faceless men before her body washes up onshore … or perhaps the stabbed dead body that washes up onshore is someone else… It’s difficult to tell. And the telling is difficult, too. And I would submit that it’s precisely these difficulties that make this gory story normal.

Three is the second of the four brilliant and enigma-ridden novels that Ann Quin published before drowning off the coast of Brighton in 1973 at the age of thirty-seven. The mysterious character S—the absent protagonist or antiheroine hypotenuse of this love-triangle tale—dies in similar fashion … or perhaps she’s stabbed to death by a gang of nameless, faceless men before her body washes up onshore … or perhaps the stabbed dead body that washes up onshore is someone else… It’s difficult to tell. And the telling is difficult, too. And I would submit that it’s precisely these difficulties that make this gory story normal. Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852), Russia’s greatest comic writer, thoroughly baffled his contemporaries. Strange, peculiar, wacky, weird, bizarre, and other words indicating enigmatic oddity recur in descriptions of him. “What an intelligent, queer, and sick creature!” remarked Turgenev; another major prose writer, Sergey Aksakov, referred to the “unintelligible strangeness of his spirit.” When Gogol died, the poet Pyotr Vyazemsky sighed, “Your life was an enigma, so is today your death.”

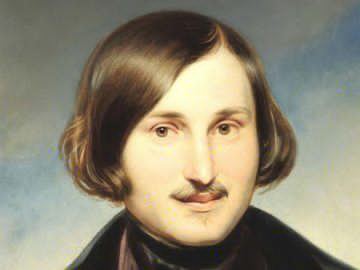

Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852), Russia’s greatest comic writer, thoroughly baffled his contemporaries. Strange, peculiar, wacky, weird, bizarre, and other words indicating enigmatic oddity recur in descriptions of him. “What an intelligent, queer, and sick creature!” remarked Turgenev; another major prose writer, Sergey Aksakov, referred to the “unintelligible strangeness of his spirit.” When Gogol died, the poet Pyotr Vyazemsky sighed, “Your life was an enigma, so is today your death.” Five years had passed since Czar Alexander II promised the emancipation of the serfs. Trusting in a map drawn on bark with the point of a knife by a Tungus hunter, three Russian scientists set out to explore an area of trackless mountain wilderness stretching across eastern Siberia. Their mission was to find a direct passage between the gold mines of the river Lena and Transbaikalia. Their discoveries would transform understanding of the geography of northern Asia, opening up the route eventually followed by the Trans-Manchurian Railway. For one explorer, now better known as an anarchist than a scientist, this expedition was also the start of a long journey towards a new articulation of evolution and the strongest possible argument for a social revolution.

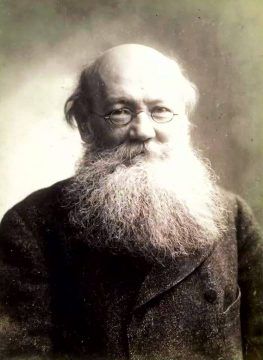

Five years had passed since Czar Alexander II promised the emancipation of the serfs. Trusting in a map drawn on bark with the point of a knife by a Tungus hunter, three Russian scientists set out to explore an area of trackless mountain wilderness stretching across eastern Siberia. Their mission was to find a direct passage between the gold mines of the river Lena and Transbaikalia. Their discoveries would transform understanding of the geography of northern Asia, opening up the route eventually followed by the Trans-Manchurian Railway. For one explorer, now better known as an anarchist than a scientist, this expedition was also the start of a long journey towards a new articulation of evolution and the strongest possible argument for a social revolution. Dear Dan,

Dear Dan, You can do whatever you want with your morals, forgive people or not. But your duties as a citizen are somewhat different than the duties you might have as, say, a Christian (the kind who strives to follow the gospel), and here forgiveness is not so much what is required as, simply, recognition of a common plight. This civic virtue overlaps, admittedly, with the moral; it is difficult to articulate it in terms that do not come across as moralising, and certainly it would be an impediment to its realisation to articulate it in the bare terms of calculative strategy. In France it is traditionally articulated in terms of fraternité, which seems to strike just the right note between strategy and moralising. We need to hold things together somehow; in a real family unit this might have to pass through an overtly moral gesture of forgiveness, but in a polity what we should perhaps expect is that people aspire at least to a recognition of their fellow citizens through a lens that represents them as brothers and sisters.

You can do whatever you want with your morals, forgive people or not. But your duties as a citizen are somewhat different than the duties you might have as, say, a Christian (the kind who strives to follow the gospel), and here forgiveness is not so much what is required as, simply, recognition of a common plight. This civic virtue overlaps, admittedly, with the moral; it is difficult to articulate it in terms that do not come across as moralising, and certainly it would be an impediment to its realisation to articulate it in the bare terms of calculative strategy. In France it is traditionally articulated in terms of fraternité, which seems to strike just the right note between strategy and moralising. We need to hold things together somehow; in a real family unit this might have to pass through an overtly moral gesture of forgiveness, but in a polity what we should perhaps expect is that people aspire at least to a recognition of their fellow citizens through a lens that represents them as brothers and sisters.