Category: Archives

N.H. Pritchard’s ‘The Matrix’

Quinn Latimer at Poetry Magazine:

What is the matrix? Without resorting to pharmaceuticals in various chromatic registers—red, blue—and the versions of paranoid reality such pills might produce, it feels right to recall the ways this concept has been deployed in mediums neither cinematic nor far-right political. In the early 1990s, Kevin Young wrote in an essay about the poet N.H. Pritchard, “The concept of the matrix is that the matrix is the concept, or rather, the paradigm from which the poem gets produced.” That is, the matrix is abstract structure that, as the French literary theorist Michael Riffaterre writes in Semiotics of Poetry (1978), “becomes visible only in its variants, the ungrammaticalities.” For James Edward Smethurst, the matrix is the Black Arts Matrix of the late 20th century, as tracked in “Foreground and Underground: the Left, Nationalism, and the Origins of the Black Arts Matrix,” the first chapter in his treatise The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s (2005).

What is the matrix? Without resorting to pharmaceuticals in various chromatic registers—red, blue—and the versions of paranoid reality such pills might produce, it feels right to recall the ways this concept has been deployed in mediums neither cinematic nor far-right political. In the early 1990s, Kevin Young wrote in an essay about the poet N.H. Pritchard, “The concept of the matrix is that the matrix is the concept, or rather, the paradigm from which the poem gets produced.” That is, the matrix is abstract structure that, as the French literary theorist Michael Riffaterre writes in Semiotics of Poetry (1978), “becomes visible only in its variants, the ungrammaticalities.” For James Edward Smethurst, the matrix is the Black Arts Matrix of the late 20th century, as tracked in “Foreground and Underground: the Left, Nationalism, and the Origins of the Black Arts Matrix,” the first chapter in his treatise The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s (2005).

more here.

N.H. Pritchard – 8 Poems from Destinations

Fragonard Up Close

Jerry Saltz at New York Magazine:

What’s so fantastic about seeing these paintings at the Frick Breuer is not only how close you can get to the work, now that it’s not surrounded with furniture and bric-a-brac. In the mansion, the Fragonards are installed — even swaddled and segregated — in a wonderful Rococo drawing room, with attendant panels over doors and next to windows. Here, the work is given pride of place on the fourth floor next to the gigantic trapezoidal window looking out over Madison Avenue. Up close and at eye level, the work is reborn as these huge heraldic thunderous paintings, visually vehement and emotionally commanding. I love them more than I ever have.

What’s so fantastic about seeing these paintings at the Frick Breuer is not only how close you can get to the work, now that it’s not surrounded with furniture and bric-a-brac. In the mansion, the Fragonards are installed — even swaddled and segregated — in a wonderful Rococo drawing room, with attendant panels over doors and next to windows. Here, the work is given pride of place on the fourth floor next to the gigantic trapezoidal window looking out over Madison Avenue. Up close and at eye level, the work is reborn as these huge heraldic thunderous paintings, visually vehement and emotionally commanding. I love them more than I ever have.

The original four pictures show narratives of flirtation, courtship, clandestine meeting, quixotic love, adventurousness, allure gone right and wrong.

more here.

When illness is invisible

Alice Robb in New Spectator:

When the London-based neurologist Suzanne O’Sullivan flew to Sweden to visit a sick girl in a small town north-west of Stockholm, the child did not acknowledge her. Not when O’Sullivan entered her bedroom, or when she knelt down to introduce herself, or even when she examined her. Nola (not her real name) wasn’t trying to be rude. It had been more than a year since she had got out of bed, opened her eyes or moved at all. A feeding tube, taped to her cheek, kept her alive.

When the London-based neurologist Suzanne O’Sullivan flew to Sweden to visit a sick girl in a small town north-west of Stockholm, the child did not acknowledge her. Not when O’Sullivan entered her bedroom, or when she knelt down to introduce herself, or even when she examined her. Nola (not her real name) wasn’t trying to be rude. It had been more than a year since she had got out of bed, opened her eyes or moved at all. A feeding tube, taped to her cheek, kept her alive.

Yet her vital signs were normal; medical tests found nothing amiss. Nola was suffering from a mystery illness known as “resignation syndrome” that afflicts hundreds of children in Sweden. The first cases were officially documented in the early 2000s: children were falling into a sleep so deep that – for days, weeks, even years – they could not be roused. Whatever their parents tried, they did not respond. If the children were pulled into an upright position, they fell back, limp, like rag dolls. The children were sent to the hospital, where doctors performed every test they could think of. Cat scans and blood tests came back normal. EEGs showed brainwaves that zigged and zagged in a healthy pattern. Blood and urine analyses ruled out the possibility that they had been poisoned. The children’s physiology was normal, and their psychology was inaccessible; they were hardly able to fill out Rorschach tests or talk about their past. It was their unique social circumstances that gave clues into their condition. All of the children were refugees, and they had gone to bed during the long process of applying for asylum. When they fell asleep, they were facing deportation to countries they scarcely remembered, where their families had suffered severe trauma.

Nola and her family were members of the persecuted Yazidi minority. When they fled their home in rural Syria, Nola’s mother was facing death threats as a result of being assaulted by four men. They arrived in Sweden when Nola was a toddler – her age was estimated at around two and a half – and were granted temporary residency. (When O’Sullivan met her in 2018, Nola was thought to be about ten.) As their parents embarked on the lengthy journey towards permanent asylum, Nola and her siblings settled happily into their new home, becoming fluent in Swedish and making such close friends that, months after Nola stopped speaking, they continued to visit her at home. It was after receiving the news that their application had been refused – via a letter that Nola and her siblings had to translate for their parents – that she began to withdraw.

More here.

Thursday Poem

In the Bowl of this World

In the bowl of this world

Look at the rose of our passion, my friend

Even if we don’t eat together

Even if we don’t sit together

We can at least dream together, my friend

Even if we don’t drink together

Even if we are strangers

Let us consider the colour of our wine, my friend

The sun is setting on the lanes

The river is almost at my door

Let us examine our restless hearts, my friend

by Rifat Abbas

from Poetry Translation Center

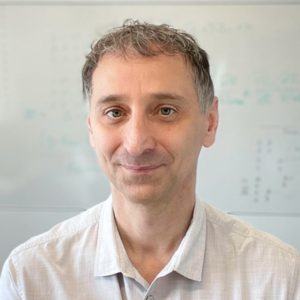

Consciousness Is Just a Feeling

Steve Paulson in Nautilus:

When he was a boy, Mark Solms obsessed over big existential questions. What happens when I die? What makes me who I am? He went on to study neuroscience but soon discovered that neuropsychology had no patience for such open-ended questions about the psyche. So Solms did something unheard of for a budding scientist. He reclaimed Freud as a founding father of neuroscience and launched a new field, neuropsychoanalysis. I reached Solms in Cape Town, South Africa, where he’s stayed during the COVID-19 lockdown. We talked about the brain-mind problem, the biases of neuropsychology and how a family trauma shaped the course of his life.

There are huge debates about the science of consciousness. Explaining the causal connection between brain and mind is one of the most difficult problems in all of science. On the one hand, there are the neurons and synaptic connections in the brain. And then there’s the immaterial world of thinking and feeling. It seems like they exist in two entirely separate domains. How do you approach this problem?

Subjective experience—consciousness—surely is part of nature because we are embodied creatures and we are experiencing subjects. So there are two ways in which you can look on the great problem you’ve just mentioned. You can either say it’s impossibly difficult to imagine how the physical organ becomes the experiencing subject, so they must belong to two different universes and therefore, the subjective experience is incomprehensible and outside of science. But it’s very hard for me to accept a view like that. The alternative is that it must somehow be possible to bridge that divide.

The major point of contention is whether consciousness can be reduced to the laws of physics or biology. The philosopher David Chalmers has speculated that consciousness is a fundamental property of nature that’s not reducible to any laws of nature.

I accept that, except for the word “fundamental.” I argue that consciousness is a property of nature, but it’s not a fundamental property. It’s quite easy to argue that there was a big bang very long ago and long after that, there was an emergence of life. If Chalmers’ view is that consciousness is a fundamental property of the universe, it must have preceded even the emergence of life. I know there are people who believe that. But as a scientist, when you look at the weight of the evidence, it’s just so much less plausible that there was already some sort of elementary form of consciousness even at the moment of the Big Bang. That’s basically the same as the idea of God. It’s not really grappling with the problem.

More here.

Wednesday, March 31, 2021

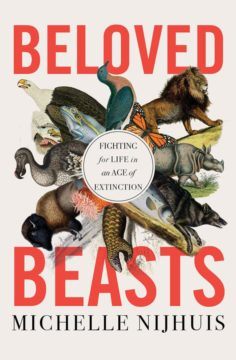

An Open-Eyed History of Wildlife Conservation

Rachel Love Nuwer in Undark:

Today’s conservationists are taxed with protecting the living embodiments of tens of millions of years of nature’s creation, and they face unprecedented challenges for doing so — from climate change and habitat destruction to pollution and unsustainable wildlife trade. Given that extinction is the price for failure, there’s little forgiveness for error. Success requires balancing not just the complexities of species and habitats, but also of people and politics. With an estimated 1 million species now threatened with extinction, conservationists need all the help they can get.

Today’s conservationists are taxed with protecting the living embodiments of tens of millions of years of nature’s creation, and they face unprecedented challenges for doing so — from climate change and habitat destruction to pollution and unsustainable wildlife trade. Given that extinction is the price for failure, there’s little forgiveness for error. Success requires balancing not just the complexities of species and habitats, but also of people and politics. With an estimated 1 million species now threatened with extinction, conservationists need all the help they can get.

Yet the past — a key repository of lessons hard learned through trial and error — is all too often forgotten or overlooked by conservation practitioners today. In “Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction,” journalist Michelle Nijhuis shows that history can help contextualize and guide modern conservation. Indeed, arguably it’s only in the last 200 years or so that a few scattered individuals began thinking seriously about the need to save species — and it’s only in the last 50 that conservation biology even emerged as a distinct field.

“Beloved Beasts” reads as a who’s who and greatest-moments survey of these developmental decades.

More here.

Carlo Rovelli on his search for the theory of everything

Marcus Chown in Prospect:

Rovelli has written a new book. Its title, Helgoland, refers to a barren island off the North Sea coast of Germany, where the 23-year-old physicist Werner Heisenberg (who would go on to work on the unrealised Nazi atomic bomb) retreated in June 1925. He was trying to make sense of recent atomic experiments, which had revealed an Alice in Wonderland submicroscopic realm where a single atom could be in two places at once; where events happened for no reason at all; and where atoms could influence each other instantaneously—even if on opposite sides of the universe.

Rovelli has written a new book. Its title, Helgoland, refers to a barren island off the North Sea coast of Germany, where the 23-year-old physicist Werner Heisenberg (who would go on to work on the unrealised Nazi atomic bomb) retreated in June 1925. He was trying to make sense of recent atomic experiments, which had revealed an Alice in Wonderland submicroscopic realm where a single atom could be in two places at once; where events happened for no reason at all; and where atoms could influence each other instantaneously—even if on opposite sides of the universe.

Heisenberg’s breakthrough was to realise that, as far as atoms and their components are concerned, everything is interaction. Subatomic particles such as electrons and photons are not objects that exist independently of being prodded and poked, but merely the sum total of their interactions with the rest of the world. “Basically, physics confirmed what several philosophers over the centuries have suspected—that the world is a web of interactions and nothing exists independently of that web,” Rovelli tells me. “It is at the atomic and subatomic, or quantum, level that we confront this truth most dramatically.”

More here.

Yuval Noah Harari in a wide-ranging conversation with Jay Shetty

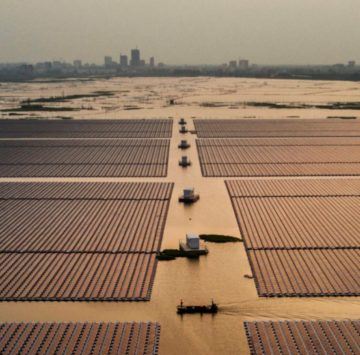

Is Climate Change a Foreign Policy Issue?

Seaver Wang in The New Atlantis:

In the Himalayas and the Middle East, countries feud over water. In the African Sahel, farmers feud over cropland. In the melting Arctic, governments feud over seabed minerals. Climate change has provided bottomless inspiration for aspiring paperback novelists. But while thrillers must thrill and generals must fret, fears about the national security threats that climate change could present remain too vague to act on. The geopolitical reasons for a strong U.S. response to climate change lie not in what Americans might imagine about tomorrow’s world politics but in the global political relationships at stake today.

In the Himalayas and the Middle East, countries feud over water. In the African Sahel, farmers feud over cropland. In the melting Arctic, governments feud over seabed minerals. Climate change has provided bottomless inspiration for aspiring paperback novelists. But while thrillers must thrill and generals must fret, fears about the national security threats that climate change could present remain too vague to act on. The geopolitical reasons for a strong U.S. response to climate change lie not in what Americans might imagine about tomorrow’s world politics but in the global political relationships at stake today.

The imagined scenario goes something like this: The world fails to halt climate change in the coming decades and remains dependent on fossil fuels. A warming climate produces greater resource scarcity, leading to more frequent wars and mass displacement of people. Global crises over energy supplies threaten the U.S. economy and international treaties, and soldiers get pulled into resource wars to protect American interests and allies.

These visions of the future might make good ammunition for Hollywood, but they provide a far too narrow, distant, and pessimistic frame for climate change as a U.S. foreign policy issue.

More here.

The Angel of Death

Why Computers Won’t Make Themselves Smarter

Ted Chiang at The New Yorker:

Some proponents of an intelligence explosion argue that it’s possible to increase a system’s intelligence without fully understanding how the system works. They imply that intelligent systems, such as the human brain or an A.I. program, have one or more hidden “intelligence knobs,” and that we only need to be smart enough to find the knobs. I’m not sure that we currently have many good candidates for these knobs, so it’s hard to evaluate the reasonableness of this idea. Perhaps the most commonly suggested way to “turn up” artificial intelligence is to increase the speed of the hardware on which a program runs. Some have said that, once we create software that is as intelligent as a human being, running the software on a faster computer will effectively create superhuman intelligence. Would this lead to an intelligence explosion?

Some proponents of an intelligence explosion argue that it’s possible to increase a system’s intelligence without fully understanding how the system works. They imply that intelligent systems, such as the human brain or an A.I. program, have one or more hidden “intelligence knobs,” and that we only need to be smart enough to find the knobs. I’m not sure that we currently have many good candidates for these knobs, so it’s hard to evaluate the reasonableness of this idea. Perhaps the most commonly suggested way to “turn up” artificial intelligence is to increase the speed of the hardware on which a program runs. Some have said that, once we create software that is as intelligent as a human being, running the software on a faster computer will effectively create superhuman intelligence. Would this lead to an intelligence explosion?

more here.

How to Write a Constitution

Linda Colley at Literary Review:

Morris’s writing took many forms. As well as maintaining a diary, he penned poems in multiple languages to the many women he seduced over the years in Europe and the United States (‘I know it to be wrong, but cannot help it’). He translated lines from Greek and Roman classics and produced pamphlets on finance and commerce. He also wrote the American constitution, quite literally. One of the fifty-odd delegates who met in Philadelphia over the summer of 1787 to draft this document, Morris chaired the constitutional convention’s ‘committee of style’ (the fact that a committee of this sort was judged desirable is suggestive). It was Morris, James Madison records, who was chiefly responsible for ‘the finish given to the style and arrangement’ of the American constitution. Most dramatically, it was he who replaced its initial matter-of-fact opening with one of the most influential phrases – and pieces of fiction – ever devised: ‘We the People of the United States…’

Morris’s writing took many forms. As well as maintaining a diary, he penned poems in multiple languages to the many women he seduced over the years in Europe and the United States (‘I know it to be wrong, but cannot help it’). He translated lines from Greek and Roman classics and produced pamphlets on finance and commerce. He also wrote the American constitution, quite literally. One of the fifty-odd delegates who met in Philadelphia over the summer of 1787 to draft this document, Morris chaired the constitutional convention’s ‘committee of style’ (the fact that a committee of this sort was judged desirable is suggestive). It was Morris, James Madison records, who was chiefly responsible for ‘the finish given to the style and arrangement’ of the American constitution. Most dramatically, it was he who replaced its initial matter-of-fact opening with one of the most influential phrases – and pieces of fiction – ever devised: ‘We the People of the United States…’

more here.

Wednesday Poem

Invitations

To rhetoric: quarry me

for the stones of such tombs as may rise

in your honor.

To molecules: let me be carbon.

To the burners of bones: let me be charcoal.

To drosophila: declaim me

of finger bananas.

To eyes: that they might look askance

in the darkness and find me.

by Campbell McGrath

from Nouns and Verbs

Harper Collins, 2019

Puzzling Through Our Eternal Quest for Wellness

Rachel Syme in The New Yorker:

About halfway through a recent episode of “POOG,” a new podcast that is essentially one long, unbroken conversation about “wellness” between the comedians and longtime friends Kate Berlant and Jacqueline Novak, the hosts spend several minutes trying—and failing—to devise a grand theory about the existential sorrow of eating ice cream. “The pleasure of eating an ice-cream cone for me,” Novak says, in the blustery tone of a motivational speaker, “involves the attempt to contain, catch up, stay present to the cone. Because the cone will not wait.” Berlant, a seasoned improviser, leaps into the game. “And it’s grief,” she says, with no trace of irony. “And it’s loss, because it’s so beautiful, it’s handed to you, and you’re constantly having to reckon with the fact that it is dying, and yet you’re experiencing it.”

About halfway through a recent episode of “POOG,” a new podcast that is essentially one long, unbroken conversation about “wellness” between the comedians and longtime friends Kate Berlant and Jacqueline Novak, the hosts spend several minutes trying—and failing—to devise a grand theory about the existential sorrow of eating ice cream. “The pleasure of eating an ice-cream cone for me,” Novak says, in the blustery tone of a motivational speaker, “involves the attempt to contain, catch up, stay present to the cone. Because the cone will not wait.” Berlant, a seasoned improviser, leaps into the game. “And it’s grief,” she says, with no trace of irony. “And it’s loss, because it’s so beautiful, it’s handed to you, and you’re constantly having to reckon with the fact that it is dying, and yet you’re experiencing it.”

From here, the conversation begins to warp into almost sublime absurdity. Novak suggests that what she ultimately desires is not the cone itself but the emptiness that comes after the cone has been consumed, or what she calls “the dead endlessness of infinite possibility.” She makes several attempts to refine this idea, in a state of increasing agitation. And then she begins to cry. “Are you crying because you are still untangling what this theory is?” Berlant asks. “No,” Novak blubbers. “I’m crying out of the humiliation of being seen as I am.”

At first, listening to this meltdown, I wondered what, precisely, was going on. Novak and Berlant are brilliant comics, denizens of the alternative-standup scene that bridges the gap between punch lines and performance art. They had to be up to something. And then, after several incantatory hours of listening to them talk, it became clear: “poog” is a show about wellness which is, in a dazzling and purposefully deranged way, utterly unwell. Of course Novak can’t process her desire to have everything and nothing at once; like so much of the language of being “healthy” in a fractured world, her yearning can never compute. “poog” is not just “Goop” (as in Gwyneth Paltrow’s life-style empire) spelled backward—it’s an attempt to push the wellness industrial complex fully through the looking glass. Each episode begins the same way. “This is our hobby,” Berlant says. “This is our hell,” Novak adds. “This is our naked desire for free products,” Berlant concludes.

More here.

Your Immune System Evolves To Fight Coronavirus Variants

Monique Brouillette in Scientific American:

A lot of worry has been triggered by discoveries that variants of the pandemic-causing coronavirus can be more infectious than the original. But now scientists are starting to find some signs of hope on the human side of this microbe-host interaction. By studying the blood of COVID survivors and people who have been vaccinated, immunologists are learning that some of our immune system cells—which remember past infections and react to them—might have their own abilities to change, countering mutations in the virus. What this means, scientists think, is that the immune system might have evolved its own way of dealing with variants.

A lot of worry has been triggered by discoveries that variants of the pandemic-causing coronavirus can be more infectious than the original. But now scientists are starting to find some signs of hope on the human side of this microbe-host interaction. By studying the blood of COVID survivors and people who have been vaccinated, immunologists are learning that some of our immune system cells—which remember past infections and react to them—might have their own abilities to change, countering mutations in the virus. What this means, scientists think, is that the immune system might have evolved its own way of dealing with variants.

“Essentially, the immune system is trying to get ahead of the virus,” says Michel Nussenzweig, an immunologist at the Rockefeller University, who conducted some recent studies that tracked this phenomenon. The emerging idea is that the body maintains reserve armies of antibody-producing cells in addition to the original cells that responded to the initial invasion by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Over time some reserve cells mutate and produce antibodies that are better able to recognize new viral versions. “It’s really elegant mechanism that that we’ve evolved, basically, to be able to handle things like variants,” says Marion Pepper, an immunologist at the University of Washington, who was not involved in Nussenzweig’s research. Whether there are enough of these cells, and their antibodies, to confer protection against a shape-shifting SARS-CoV-2 is still being figured out.

More here.

Tuesday, March 30, 2021

Is credentialism “the last acceptable prejudice”?

Jonathan B. Imber in The Hedgehog Review:

As we learn in The Tyranny of Merit, Michael Sandel’s view of meritocracy rests in part on the historical claim that it is grounded in the Calvinist understanding of predestination. “Combined with the idea that the elect must prove their election through work in a calling,” he writes, such a doctrine “leads to the notion that worldly success is a good indication of who is destined for salvation.” In this he follows Max Weber in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, but Sandel extends this thesis to the present moment, citing the evangelical idea of the “prosperity gospel” and the secular rationalizations of such well-known achievers as Lloyd Blankfein (CEO of Goldman Sachs) and John Mackey (founder of Whole Foods), who represent the understanding of health and wealth “as matters of praise and blame…a meritocratic way of looking at life.”

As we learn in The Tyranny of Merit, Michael Sandel’s view of meritocracy rests in part on the historical claim that it is grounded in the Calvinist understanding of predestination. “Combined with the idea that the elect must prove their election through work in a calling,” he writes, such a doctrine “leads to the notion that worldly success is a good indication of who is destined for salvation.” In this he follows Max Weber in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, but Sandel extends this thesis to the present moment, citing the evangelical idea of the “prosperity gospel” and the secular rationalizations of such well-known achievers as Lloyd Blankfein (CEO of Goldman Sachs) and John Mackey (founder of Whole Foods), who represent the understanding of health and wealth “as matters of praise and blame…a meritocratic way of looking at life.”

Sandel, a professor of political philosophy at Harvard University, believes that two accounts of what constitutes a just society have been made in market terms. He calls one “free-market liberalism” (or “neoliberalism”) and the other “welfare state liberalism” (or “egalitarian liberalism”). Neither has adequately explained or proposed ways to restrain inequality. The same is especially true of libertarian philosophers, or “luck egalitarians,” who justify inequality by distinguishing between those who are responsible for their misfortunes and those who are victims of bad luck. Meanwhile, the progressive investment in education has had the unintended consequence of widening inequality: “The weaponization of college credentials,” Sandel notes, “shows how merit can become a kind of tyranny.” One damaging effect of this is the “eroding of social esteem accorded those who had not gone to college,” which is particularly bad when you remember that only about one in three American adults graduates from a four-year college.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Dean Buonomano on Time, Reality, and the Brain

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

“Time” and “the brain” are two of those things that are somewhat mysterious, but it would be hard for us to live without. So just imagine how much fun it is to bring them together. Dean Buonomano is one of the leading neuroscientists studying how our brains perceive time, which is part of the bigger issue of how we construct models of the physical world around us. We talk about how the brain tells time very differently than the clocks that we’re used to, using different neuronal mechanisms for different timescales. This brings us to a very interesting conversation about the nature of time itself — Dean is a presentist, who believes that only the current moment qualifies as “real,” but we don’t hold that against him.

“Time” and “the brain” are two of those things that are somewhat mysterious, but it would be hard for us to live without. So just imagine how much fun it is to bring them together. Dean Buonomano is one of the leading neuroscientists studying how our brains perceive time, which is part of the bigger issue of how we construct models of the physical world around us. We talk about how the brain tells time very differently than the clocks that we’re used to, using different neuronal mechanisms for different timescales. This brings us to a very interesting conversation about the nature of time itself — Dean is a presentist, who believes that only the current moment qualifies as “real,” but we don’t hold that against him.

More here.