Alex Hanna, Emily Denton, Razvan Amironesei, Andrew Smart, and Hilary Nicole in Logic:

Alex Hanna, Emily Denton, Razvan Amironesei, Andrew Smart, and Hilary Nicole in Logic:

On the night of March 18, 2018, Elaine Herzberg was walking her bicycle across a dark desert road in Tempe, Arizona. After crossing three lanes of a four-lane highway, a “self-driving” Volvo SUV, traveling at thirty-eight miles per hour, struck her. Thirty minutes later, she was dead. The SUV had been operated by Uber, part of a fleet of self-driving car experiments operating across the state. A report by the National Transportation and Safety Board determined that the car’s sensors had detected an object in the road six seconds before the crash, but the software “did not include a consideration for jaywalking pedestrians.” In the moments before the car hit Elaine, its AI software cycled through several potential identifiers for her—including “bicycle,” “vehicle,” and “other”—but, ultimately, was not able to recognize her as a pedestrian whose trajectory would be imminently in the collision path of the vehicle.

How did this happen? The particular kind of AI at work in autonomous vehicles is called machine learning. Machine learning enables computers to “learn” certain tasks by analyzing data and extracting patterns from it. In the case of self-driving cars, the main task that the computer must learn is how to see. More specifically, it must learn how to perceive and meaningfully describe the visual world in a manner comparable to humans. This is the field of computer vision, and it encompasses a wide range of controversial and consequential applications, from facial recognition to drone strike targeting.

Unlike in traditional software development, machine learning engineers do not write explicit rules that tell a computer exactly what to do. Rather, they enable a computer to “learn” what to do by discovering patterns in data. The information used for teaching computers is known as training data. Everything a machine learning model knows about the world comes from the data it is trained on.

More here.

Marta Figlerowicz in Boston Review:

Marta Figlerowicz in Boston Review: McMurtry

McMurtry Forty years is a long time. I have to say that India is no longer the country of this novel. When I wrote Midnight’s Children I had in mind an arc of history moving from the hope – the bloodied hope, but still the hope – of independence to the betrayal of that hope in the so-called Emergency, followed by the birth of a new hope. India today, to someone of my mind, has entered an even darker phase than the Emergency years. The horrifying escalation of assaults on women, the increasingly authoritarian character of the state, the unjustifiable arrests of people who dare to stand against that authoritarianism, the religious fanaticism, the rewriting of history to fit the narrative of those who want to transform India into a Hindu-nationalist, majoritarian state, and the popularity of the regime in spite of it all, or, worse, perhaps because of it all – these things encourage a kind of despair.

Forty years is a long time. I have to say that India is no longer the country of this novel. When I wrote Midnight’s Children I had in mind an arc of history moving from the hope – the bloodied hope, but still the hope – of independence to the betrayal of that hope in the so-called Emergency, followed by the birth of a new hope. India today, to someone of my mind, has entered an even darker phase than the Emergency years. The horrifying escalation of assaults on women, the increasingly authoritarian character of the state, the unjustifiable arrests of people who dare to stand against that authoritarianism, the religious fanaticism, the rewriting of history to fit the narrative of those who want to transform India into a Hindu-nationalist, majoritarian state, and the popularity of the regime in spite of it all, or, worse, perhaps because of it all – these things encourage a kind of despair. Carl Zimmer’s book begins with a bang. Not a Big Bang, but a small one. In the fall of 1904, a 31-year-old physicist, John Butler Burke, working at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge University, made a “bouillon” of chunks of boiled beef in water. To this mix, he added a dab of radium, the newly discovered element glowing with radioactive energy, and waited overnight. The next morning, he skimmed the radioactive soup, smeared a layer on a glass slide and placed it under a microscope. He saw spicules of coalesced matter — “radiobes,” as he called them — that resembled, to his eyes, the most primeval forms of life.

Carl Zimmer’s book begins with a bang. Not a Big Bang, but a small one. In the fall of 1904, a 31-year-old physicist, John Butler Burke, working at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge University, made a “bouillon” of chunks of boiled beef in water. To this mix, he added a dab of radium, the newly discovered element glowing with radioactive energy, and waited overnight. The next morning, he skimmed the radioactive soup, smeared a layer on a glass slide and placed it under a microscope. He saw spicules of coalesced matter — “radiobes,” as he called them — that resembled, to his eyes, the most primeval forms of life. The continuity stretching from the earlier flower and plant paintings to the landscape work in New Mexico comes from O’Keeffe’s lifelong obsession with looking at things. I mean that quite literally. How do you look at a thing? How do you see a thing? Well, you just look, don’t you? But O’Keeffe’s answer is, “No, you don’t just look, because you don’t know how to look.” So what’s the difference between looking in the normal way and looking in the O’Keeffe way? Much of it has to do with time. O’Keeffe liked to look at things for a long time. She’d stare at a single flower over and over again, hour after hour. We think we know what that means. But do we? I suspect the actual experience is crucial here. That’s to say, don’t assume you know what it means to look at one thing hour after hour unless you’ve done it. I’ve done it, sort of. I stared at a flower once more or less without interruption for over an hour. It was immensely difficult for the first twenty minutes or so. Then something changed. My vision started to surrender to something else. Everything suddenly slowed down and intensified. I started to see the flower as a whole, as well as the tiny individual parts, simultaneously. A kind of meditational state kicked in. My vision became a form, almost, of physical touching. It was sensuous and sensual, which is why all the critics who’ve talked about the sensuality of O’Keeffe’s flower paintings are not completely wrong.

The continuity stretching from the earlier flower and plant paintings to the landscape work in New Mexico comes from O’Keeffe’s lifelong obsession with looking at things. I mean that quite literally. How do you look at a thing? How do you see a thing? Well, you just look, don’t you? But O’Keeffe’s answer is, “No, you don’t just look, because you don’t know how to look.” So what’s the difference between looking in the normal way and looking in the O’Keeffe way? Much of it has to do with time. O’Keeffe liked to look at things for a long time. She’d stare at a single flower over and over again, hour after hour. We think we know what that means. But do we? I suspect the actual experience is crucial here. That’s to say, don’t assume you know what it means to look at one thing hour after hour unless you’ve done it. I’ve done it, sort of. I stared at a flower once more or less without interruption for over an hour. It was immensely difficult for the first twenty minutes or so. Then something changed. My vision started to surrender to something else. Everything suddenly slowed down and intensified. I started to see the flower as a whole, as well as the tiny individual parts, simultaneously. A kind of meditational state kicked in. My vision became a form, almost, of physical touching. It was sensuous and sensual, which is why all the critics who’ve talked about the sensuality of O’Keeffe’s flower paintings are not completely wrong. Artificial-intelligence systems are nowhere near advanced enough to replace humans in many tasks involving reasoning, real-world knowledge, and social interaction. They are showing human-level competence in low-level pattern recognition skills, but at the cognitive level they are merely imitating human intelligence, not engaging deeply and creatively, says

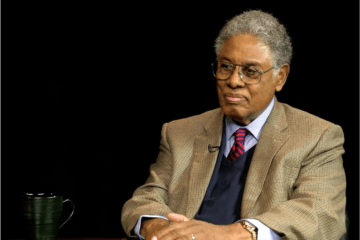

Artificial-intelligence systems are nowhere near advanced enough to replace humans in many tasks involving reasoning, real-world knowledge, and social interaction. They are showing human-level competence in low-level pattern recognition skills, but at the cognitive level they are merely imitating human intelligence, not engaging deeply and creatively, says  Somewhere out of the mysterious interplay between nature and nurture, internal and external factors, cultures and structures, and bottom-up and top-down forces there emerge the individual and group outcomes that we care about and which ultimately make the difference between human flourishing and its absence. What distinguishes various political ideologies, in effect, is how the line of causation is drawn, or, more specifically, from which direction. What gets left unexamined in the rush for compelling narratives and ideological certainty, however, is the territory between different causes and how they combine to shape reality. Few have gone further to map that territory than the American economist, political philosopher, and public intellectual Thomas Sowell.

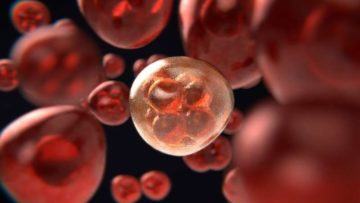

Somewhere out of the mysterious interplay between nature and nurture, internal and external factors, cultures and structures, and bottom-up and top-down forces there emerge the individual and group outcomes that we care about and which ultimately make the difference between human flourishing and its absence. What distinguishes various political ideologies, in effect, is how the line of causation is drawn, or, more specifically, from which direction. What gets left unexamined in the rush for compelling narratives and ideological certainty, however, is the territory between different causes and how they combine to shape reality. Few have gone further to map that territory than the American economist, political philosopher, and public intellectual Thomas Sowell. In the study, investigators reported the extensive presence of mouse viruses in patient-derived xenografts (PDX). PDX models are developed by implanting human tumor tissues in immune-deficient mice, and are commonly used to help test and develop

In the study, investigators reported the extensive presence of mouse viruses in patient-derived xenografts (PDX). PDX models are developed by implanting human tumor tissues in immune-deficient mice, and are commonly used to help test and develop  According to the late Christopher Lasch, the advent of mass production and the new relations of authority it introduced in every sphere of social life wrought a fateful change in the prevailing American character. Psychological maturation—as Lasch, relying on Freud, explicated it—depended crucially on face-to-face relations, on a rhythm and a scale that industrialism disrupted. The result was a weakened, malleable self, more easily regimented than its pre-industrial forebear, less able to withstand conformist pressures and bureaucratic manipulation—the antithesis of the rugged individualism that had undergirded the republican virtues.

According to the late Christopher Lasch, the advent of mass production and the new relations of authority it introduced in every sphere of social life wrought a fateful change in the prevailing American character. Psychological maturation—as Lasch, relying on Freud, explicated it—depended crucially on face-to-face relations, on a rhythm and a scale that industrialism disrupted. The result was a weakened, malleable self, more easily regimented than its pre-industrial forebear, less able to withstand conformist pressures and bureaucratic manipulation—the antithesis of the rugged individualism that had undergirded the republican virtues. The first note known to have sounded on earth was an E natural. It was produced some 165 million years ago by a katydid (a kind of cricket) rubbing its wings together, a fact deduced by scientists from the remains of one of these insects, preserved in amber. Consider, too, the love life of the mosquito. When a male mosquito wishes to attract a mate, his wings buzz at a frequency of 600Hz, which is the equivalent of D natural. The normal pitch of the female’s wings is 400Hz, or G natural. Just prior to sex, however, male and female harmonise at 1200Hz, which is, as Michael Spitzer notes in his extraordinary new book, The Musical Human, ‘an ecstatic octave above the male’s D’. ‘Everything we sing’, Spitzer adds, ‘is just a footnote to that.’

The first note known to have sounded on earth was an E natural. It was produced some 165 million years ago by a katydid (a kind of cricket) rubbing its wings together, a fact deduced by scientists from the remains of one of these insects, preserved in amber. Consider, too, the love life of the mosquito. When a male mosquito wishes to attract a mate, his wings buzz at a frequency of 600Hz, which is the equivalent of D natural. The normal pitch of the female’s wings is 400Hz, or G natural. Just prior to sex, however, male and female harmonise at 1200Hz, which is, as Michael Spitzer notes in his extraordinary new book, The Musical Human, ‘an ecstatic octave above the male’s D’. ‘Everything we sing’, Spitzer adds, ‘is just a footnote to that.’ We tested 100 participants twice on a range of tests: some took them first in summer and then winter, and some in the opposite order. Among the tasks, there was a test of pure speed (‘press this button as quickly as possible as soon as you see a circle in the middle of the screen’); a test of immediate memory for digits; a test of memory for words presented

We tested 100 participants twice on a range of tests: some took them first in summer and then winter, and some in the opposite order. Among the tasks, there was a test of pure speed (‘press this button as quickly as possible as soon as you see a circle in the middle of the screen’); a test of immediate memory for digits; a test of memory for words presented  Take a look at the numbers 294,001, 505,447 and 584,141. Notice anything special about them? You may recognize that they’re all prime — evenly divisible only by themselves and 1 — but these particular primes are even more unusual.

Take a look at the numbers 294,001, 505,447 and 584,141. Notice anything special about them? You may recognize that they’re all prime — evenly divisible only by themselves and 1 — but these particular primes are even more unusual. For several decades, child advocates have tried to bring more public indignation to the scandal of extreme child poverty, and have pushed for the expansion of the Child Tax Credit. In recent years, some progressives have called for something that seemed even more utopian, a universal basic income.

For several decades, child advocates have tried to bring more public indignation to the scandal of extreme child poverty, and have pushed for the expansion of the Child Tax Credit. In recent years, some progressives have called for something that seemed even more utopian, a universal basic income.