Sabine Hossenfelder in Scientific American:

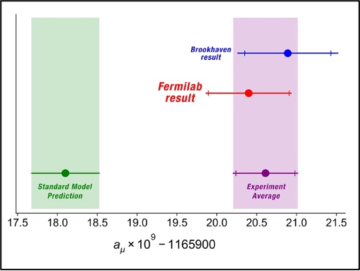

So how are we to gauge the 4.2-sigma discrepancy between the Standard Model’s prediction and the new measurement? First of all, it is helpful to remember the reason that particle physicists use the five-sigma standard to begin with. The reason is not so much that particle physics is somehow intrinsically more precise than other areas of science or that particle physicists are so much better at doing experiments. It’s primarily that particle physicists have a lot of data. And the more data you have, the more likely you are to find random fluctuations that coincidentally look like a signal. Particle physicists began to commonly use the five-sigma criterion in the mid-1990s to save themselves from the embarrassment of having too many “discoveries” that later turn out to be mere statistical fluctuations.

So how are we to gauge the 4.2-sigma discrepancy between the Standard Model’s prediction and the new measurement? First of all, it is helpful to remember the reason that particle physicists use the five-sigma standard to begin with. The reason is not so much that particle physics is somehow intrinsically more precise than other areas of science or that particle physicists are so much better at doing experiments. It’s primarily that particle physicists have a lot of data. And the more data you have, the more likely you are to find random fluctuations that coincidentally look like a signal. Particle physicists began to commonly use the five-sigma criterion in the mid-1990s to save themselves from the embarrassment of having too many “discoveries” that later turn out to be mere statistical fluctuations.

But of course five sigma is an entirely arbitrary cut, and particle physicists also discuss anomalies well below that limit. Indeed, quite a few three- and four-sigma anomalies have come and gone over the years.

More here. [Thanks to Bill Benzon.]

In 1935, one of France’s leading mathematicians, Élie Cartan, received a letter of introduction to Nicolas Bourbaki, along with an article submitted on Bourbaki’s behalf for publication in the journal Comptes rendus de l’Académie des Sciences (Proceedings of the French Academy of Sciences). The letter, written by fellow mathematician André Weil, described Bourbaki as a reclusive author passing his days playing cards in the Paris suburb of Clichy, without any pretense of overturning the foundations of all of mathematics (that more disruptive part of Bourbaki’s oeuvre and ambitions

In 1935, one of France’s leading mathematicians, Élie Cartan, received a letter of introduction to Nicolas Bourbaki, along with an article submitted on Bourbaki’s behalf for publication in the journal Comptes rendus de l’Académie des Sciences (Proceedings of the French Academy of Sciences). The letter, written by fellow mathematician André Weil, described Bourbaki as a reclusive author passing his days playing cards in the Paris suburb of Clichy, without any pretense of overturning the foundations of all of mathematics (that more disruptive part of Bourbaki’s oeuvre and ambitions

Pakistan’s prime minister Imran Khan has once again

Pakistan’s prime minister Imran Khan has once again  IN A NABOKOV short story from 1945, some cultured English people hobnob about the Dresden bombing at a cocktail party: “‘My Dresden no longer exists,’ said Mrs. Mulberry. ‘Our bombs have destroyed it and everything it meant.’” For Anglo-Americans since World War II, Dresden has become an icon of ruin, first moral then physical — a sensational reminder of the evils of war. Recent histories like Sinclair McKay’s Dresden (2020) tend to conjure the firestorm as an act of sheer destruction, a brutish assault on a culture city that, if you squinted, was comparable to Vienna or Paris. (Such accounts tend to overstate Dresden’s innocence — the city was an important site for industry and transportation.) Heavily bombed during the war, then only haltingly rebuilt by Communist East Germany (GDR), Dresden is now a global symbol for atrocity against the run of play.

IN A NABOKOV short story from 1945, some cultured English people hobnob about the Dresden bombing at a cocktail party: “‘My Dresden no longer exists,’ said Mrs. Mulberry. ‘Our bombs have destroyed it and everything it meant.’” For Anglo-Americans since World War II, Dresden has become an icon of ruin, first moral then physical — a sensational reminder of the evils of war. Recent histories like Sinclair McKay’s Dresden (2020) tend to conjure the firestorm as an act of sheer destruction, a brutish assault on a culture city that, if you squinted, was comparable to Vienna or Paris. (Such accounts tend to overstate Dresden’s innocence — the city was an important site for industry and transportation.) Heavily bombed during the war, then only haltingly rebuilt by Communist East Germany (GDR), Dresden is now a global symbol for atrocity against the run of play. The thing about big plans is that they require people to carry them out. The problem of personnel particularly plagued Peter the Great. Convinced by his European advisers that his country was backward and stuck in a medieval mindset, he spent much of his reign on a series of modernizing initiatives intended to get Russia “caught up” with the West. To implement his reforms—which included establishing a navy, imposing a tax on beards, and eventually drafting half a million serfs to build a city (named after himself) on nothing but marshland—he needed a robust bureaucracy and a standing military that could manage the demands of his new, spruced-up empire. Peter thus made service—civil or military—compulsory for the Russian nobility, and he implemented a new class system, the Table of Ranks, under which one could be promoted according to how long and how well one served.

The thing about big plans is that they require people to carry them out. The problem of personnel particularly plagued Peter the Great. Convinced by his European advisers that his country was backward and stuck in a medieval mindset, he spent much of his reign on a series of modernizing initiatives intended to get Russia “caught up” with the West. To implement his reforms—which included establishing a navy, imposing a tax on beards, and eventually drafting half a million serfs to build a city (named after himself) on nothing but marshland—he needed a robust bureaucracy and a standing military that could manage the demands of his new, spruced-up empire. Peter thus made service—civil or military—compulsory for the Russian nobility, and he implemented a new class system, the Table of Ranks, under which one could be promoted according to how long and how well one served. The long-awaited first results from the Muon g-2 experiment at the US Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory show fundamental particles called muons behaving in a way that is not predicted by scientists’ best theory, the Standard Model of particle physics. This landmark result, made with unprecedented precision, confirms a discrepancy that has been gnawing at researchers for decades.

The long-awaited first results from the Muon g-2 experiment at the US Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory show fundamental particles called muons behaving in a way that is not predicted by scientists’ best theory, the Standard Model of particle physics. This landmark result, made with unprecedented precision, confirms a discrepancy that has been gnawing at researchers for decades. It is hard to believe that it has been fifty years since I used to sit on the floor of drafty college residences in Oxford with Hussein Agha, Ahmad Samih Khalidi, Ahmad’s cousin Rashid Khalidi, and other luminaries of the Oxford University Arab Society, listening to their discussions of the then-parlous state of the Palestinian freedom movement (and voicing an occasional interjection). During the previous year, Palestinian guerrillas earlier chased out of the West Bank by Israel had proceeded to challenge King Hussein’s rule in Jordan; and during “Black” September 1970, Hussein hit back at them hard. In Spring 1971 the guerrillas were still reeling from Black September and were struggling to regroup in the extensive Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon. In Oxford we eagerly read any scrap of news we could get about their achievements there.

It is hard to believe that it has been fifty years since I used to sit on the floor of drafty college residences in Oxford with Hussein Agha, Ahmad Samih Khalidi, Ahmad’s cousin Rashid Khalidi, and other luminaries of the Oxford University Arab Society, listening to their discussions of the then-parlous state of the Palestinian freedom movement (and voicing an occasional interjection). During the previous year, Palestinian guerrillas earlier chased out of the West Bank by Israel had proceeded to challenge King Hussein’s rule in Jordan; and during “Black” September 1970, Hussein hit back at them hard. In Spring 1971 the guerrillas were still reeling from Black September and were struggling to regroup in the extensive Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon. In Oxford we eagerly read any scrap of news we could get about their achievements there. First, let’s survey the situation. It’s as though the haze of our inner lives were being filtered through a screen of therapy work sheets. If we are especially online, or roaming the worlds of friendship, wellness, activism, or romance, we must consider when we are centering ourselves or setting boundaries, sitting with our discomfort or being present. We “just want to name” a dynamic. We joke about our coping mechanisms, codependent relationships, and avoidant attachment styles. We practice self-care and shun “toxic” acquaintances. We project and decathect; we are triggered, we say wryly, adding that we dislike the word; we catastrophize, ruminate, press on the wound, process. We feel seen and we feel heard, or we feel unseen and we feel unheard, or we feel heard but not listened to, not actively. We diagnose and receive diagnoses: O.C.D., A.D.H.D., generalized anxiety disorder, depression. We’re enmeshed, fragile. Our emotional labor is grinding us down. We’re doing the work. We need to do the work.

First, let’s survey the situation. It’s as though the haze of our inner lives were being filtered through a screen of therapy work sheets. If we are especially online, or roaming the worlds of friendship, wellness, activism, or romance, we must consider when we are centering ourselves or setting boundaries, sitting with our discomfort or being present. We “just want to name” a dynamic. We joke about our coping mechanisms, codependent relationships, and avoidant attachment styles. We practice self-care and shun “toxic” acquaintances. We project and decathect; we are triggered, we say wryly, adding that we dislike the word; we catastrophize, ruminate, press on the wound, process. We feel seen and we feel heard, or we feel unseen and we feel unheard, or we feel heard but not listened to, not actively. We diagnose and receive diagnoses: O.C.D., A.D.H.D., generalized anxiety disorder, depression. We’re enmeshed, fragile. Our emotional labor is grinding us down. We’re doing the work. We need to do the work. Louis Renard

Louis Renard By all accounts, Maurice Schérer led an oppressively virtuous life. He never cheated on his wife. He was sober, refusing both drugs and alcohol, and he attended Mass each Sunday. Though he could have afforded a car, he never bought one, and he considered even occasional taxi trips an undue extravagance. In his old age, when he was suffering from painful scoliosis, he continued taking two buses to work in the Montparnasse neighborhood of Paris each morning, then the same two buses back home each night. He cherished quiet enjoyments: classical music, visits to museums, nights at home with his family. He was born in 1920 and died in 2010, but he never owned a telephone.

By all accounts, Maurice Schérer led an oppressively virtuous life. He never cheated on his wife. He was sober, refusing both drugs and alcohol, and he attended Mass each Sunday. Though he could have afforded a car, he never bought one, and he considered even occasional taxi trips an undue extravagance. In his old age, when he was suffering from painful scoliosis, he continued taking two buses to work in the Montparnasse neighborhood of Paris each morning, then the same two buses back home each night. He cherished quiet enjoyments: classical music, visits to museums, nights at home with his family. He was born in 1920 and died in 2010, but he never owned a telephone. Flyn isn’t interested so much in what we’ve done to nature as in how it bounces back. ‘What draws my attention’, she writes, ‘is not the afterglow of pristine nature as it disappears over the horizon, but the narrow band of brightening sky that might indicate a fresh dawn of a new wild as, across the world, ever more land falls into abandonment.’ More of the world being abandoned – is that right? We assume that as our numbers increase, so we claim more territory from the wild. But in fact our activity is increasingly concentrated in smaller areas and, in the developed world at least, we are leaving more land to its own devices.

Flyn isn’t interested so much in what we’ve done to nature as in how it bounces back. ‘What draws my attention’, she writes, ‘is not the afterglow of pristine nature as it disappears over the horizon, but the narrow band of brightening sky that might indicate a fresh dawn of a new wild as, across the world, ever more land falls into abandonment.’ More of the world being abandoned – is that right? We assume that as our numbers increase, so we claim more territory from the wild. But in fact our activity is increasingly concentrated in smaller areas and, in the developed world at least, we are leaving more land to its own devices. What ever happened to machines taking over the world? What was once an object of intense concern now seems like a punchline. Take one of the

What ever happened to machines taking over the world? What was once an object of intense concern now seems like a punchline. Take one of the  In a world flooded with information, everybody necessarily makes choices about what we pay attention to. This basic fact can be manipulated in any number of ways, from advertisers micro-targeting specific groups to repressive governments flooding social media with misinformation, or for that matter well-meaning people passing along news from sketchy sources. Zeynep Tufekci is a sociologist who studies the flow of information and its impact on society, especially through social media. She has provided insightful analyses of protest movements, online privacy, and the Covid-19 pandemic. We talk about how technology has been shaping the information space we all inhabit.

In a world flooded with information, everybody necessarily makes choices about what we pay attention to. This basic fact can be manipulated in any number of ways, from advertisers micro-targeting specific groups to repressive governments flooding social media with misinformation, or for that matter well-meaning people passing along news from sketchy sources. Zeynep Tufekci is a sociologist who studies the flow of information and its impact on society, especially through social media. She has provided insightful analyses of protest movements, online privacy, and the Covid-19 pandemic. We talk about how technology has been shaping the information space we all inhabit. The “rogue scholar” referred to in Michael Blandings’ captivating book, “North by Shakespeare: A Rogue Scholar’s Quest for the Truth Behind the Bard’s Work,” is a researcher who has confronted one of the most entrenched literary orthodoxies: that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the plays that bear his name.

The “rogue scholar” referred to in Michael Blandings’ captivating book, “North by Shakespeare: A Rogue Scholar’s Quest for the Truth Behind the Bard’s Work,” is a researcher who has confronted one of the most entrenched literary orthodoxies: that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote the plays that bear his name.