Brendan Greeley in the Financial Times:

The hardest thing about teaching someone how to drive a boat is that it’s not at all like driving a car. To steer a car, you turn the wheel until your nose is pointing where you want to go, then you straighten out and go there. This works because the car is attached to the road. It’s when the car itself is no longer attached to the road that things get weird. When you turn too hard, for example, the rubber in your tyres loses purchase on the street, and you are “in drift”. The normal rules no longer apply.

The hardest thing about teaching someone how to drive a boat is that it’s not at all like driving a car. To steer a car, you turn the wheel until your nose is pointing where you want to go, then you straighten out and go there. This works because the car is attached to the road. It’s when the car itself is no longer attached to the road that things get weird. When you turn too hard, for example, the rubber in your tyres loses purchase on the street, and you are “in drift”. The normal rules no longer apply.

When you drive a boat, you are always in drift. You are attached to nothing. Stuff happens in the water beneath you that does not make any intuitive sense. Sometimes your stern (your tail) moves faster than your bow (your nose), and in a different direction. Sometimes both stern and bow are moving in the same direction at the same speed, but it’s not the direction the bow is pointed. On a boat, you don’t always go where you’re pointed.

On Wednesday, the Golden-Class container ship Ever Given made an unplanned berth in the sand on both sides of the Suez Canal, stopping trade between Europe and Asia.

More here.

DIGITAL-DATA PRODUCTION

DIGITAL-DATA PRODUCTION Where do you place the boundary between “science” and “pseudoscience”? The question is more than academic. The answers we give have consequences—in part because, as health policy scholar Timothy Caulfield

Where do you place the boundary between “science” and “pseudoscience”? The question is more than academic. The answers we give have consequences—in part because, as health policy scholar Timothy Caulfield  W

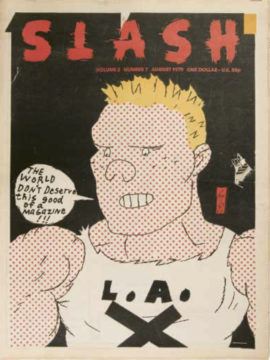

W According to Panter, he didn’t set out to create Jimbo, “he just showed up.” Jimbo made his first public appearance in the punk magazine Slash in 1977 and his cover debut two years later. His pug-nosed mug moved to Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman’s radical art-comics anthology Raw in 1981; some of Jimbo’s stories there made up the first Raw One-Shot, a spin-off of the periodical, the following year. He joined an ensemble cast in Panter’s Cola Madnes, written in 1983 but not published until 2000, and landed his first full-length book, Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise, in 1988, published by Raw and Pantheon. Jimbo has since starred in four issues of a self-titled comic published by Zongo in the nineties and stood in for Dante in two illuminated-manuscripts-cum-comic-books: Jimbo in Purgatory (2004) and Jimbo’s Inferno (2006). He is, as you read these words, being sent out into fresh adventures by Panter’s fervid imagination and tireless pen.

According to Panter, he didn’t set out to create Jimbo, “he just showed up.” Jimbo made his first public appearance in the punk magazine Slash in 1977 and his cover debut two years later. His pug-nosed mug moved to Françoise Mouly and Art Spiegelman’s radical art-comics anthology Raw in 1981; some of Jimbo’s stories there made up the first Raw One-Shot, a spin-off of the periodical, the following year. He joined an ensemble cast in Panter’s Cola Madnes, written in 1983 but not published until 2000, and landed his first full-length book, Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise, in 1988, published by Raw and Pantheon. Jimbo has since starred in four issues of a self-titled comic published by Zongo in the nineties and stood in for Dante in two illuminated-manuscripts-cum-comic-books: Jimbo in Purgatory (2004) and Jimbo’s Inferno (2006). He is, as you read these words, being sent out into fresh adventures by Panter’s fervid imagination and tireless pen. Shortly after September 11, 2001, Bruno Latour for example

Shortly after September 11, 2001, Bruno Latour for example  I am a non-white Mizrahi Jewish academic who has been studying Israel/Palestine and the history of Jews in the Middle East for two decades. My family hails from Ottoman Palestine, Egypt, Tunisia, and the Greek islands of Zakynthos and Corfu. All too many of us were murdered by Nazi Génocidaires (and rest assured that we will not forget or forgive). Precisely because of this scholarly and biographic background I was embarrassed to read the

I am a non-white Mizrahi Jewish academic who has been studying Israel/Palestine and the history of Jews in the Middle East for two decades. My family hails from Ottoman Palestine, Egypt, Tunisia, and the Greek islands of Zakynthos and Corfu. All too many of us were murdered by Nazi Génocidaires (and rest assured that we will not forget or forgive). Precisely because of this scholarly and biographic background I was embarrassed to read the  The largest animals that have ever existed on our planet descended from a miniature deer-like creature that walked on four legs in the swamps of ancient India.

The largest animals that have ever existed on our planet descended from a miniature deer-like creature that walked on four legs in the swamps of ancient India. Like other artists, the actor is a kind of shaman. If the audience is lucky, we go with this emotional magician to other worlds and other versions of ourselves. Our enchantment or immersion into another world is not just theoretical, but sensory and emotional. How do actor and audience achieve this shared mysterious transportation? This shared ritual draws upon a kind of sixth sense, the imagination. The actor’s imagination has gone into emotional territories of intense feeling before us. Now they guide us like a psychopomp into those emotional territories by recreating them in front of us.

Like other artists, the actor is a kind of shaman. If the audience is lucky, we go with this emotional magician to other worlds and other versions of ourselves. Our enchantment or immersion into another world is not just theoretical, but sensory and emotional. How do actor and audience achieve this shared mysterious transportation? This shared ritual draws upon a kind of sixth sense, the imagination. The actor’s imagination has gone into emotional territories of intense feeling before us. Now they guide us like a psychopomp into those emotional territories by recreating them in front of us. I HAVE NEVER BEEN ABLE

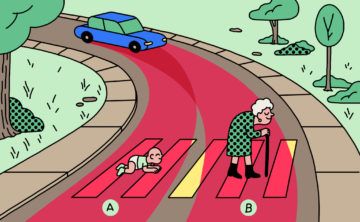

I HAVE NEVER BEEN ABLE In 2014 researchers at the MIT Media Lab designed an experiment called

In 2014 researchers at the MIT Media Lab designed an experiment called  Charlie Tyson reviews Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

Charlie Tyson reviews Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

Ari Linden in Public Books:

Ari Linden in Public Books: