Elisa Gonzalez at The Point:

But Robinson’s Christianity manifests as more than a formal approach to experience—the particulars of her belief do matter, and they serve as a foundation for the representation of American racism in the Gilead novels. With John Calvin, she shares the conviction that there is “a visionary quality to all experience” and that God animates, at every moment, all of creation. This endows that creation with immanence and revelatory potential. She believes in the existence of souls, mysterious and unaccountable and equal, which profoundly influences how she engages the material reality of racist institutions and social practices. She believes, like Calvin and the contemporary Black theologian Reggie L. Williams, that each encounter with another person is an encounter with an image of God, in effect God himself, thus placing an immense weight on the treatment of others, surpassing even the Golden Rule. Even if a man is trying to kill you, “you owe him everything.” As Calvin does, she believes that each encounter with another person is a question that God is asking of you. In a recent lecture, she described one of God’s goals for creation—which, by implication, should be a human goal—as “human flourishing.” “Flourishing” is a startling word. Its pursuit demands far more than tolerance, or even civic equality: it demands a passionate devotion to others, regardless of your connections through family, country, race or religion. For her, good and evil are relational, social—not solely internal matters. Christianity, she has said, is an ethic, not an identity.

But Robinson’s Christianity manifests as more than a formal approach to experience—the particulars of her belief do matter, and they serve as a foundation for the representation of American racism in the Gilead novels. With John Calvin, she shares the conviction that there is “a visionary quality to all experience” and that God animates, at every moment, all of creation. This endows that creation with immanence and revelatory potential. She believes in the existence of souls, mysterious and unaccountable and equal, which profoundly influences how she engages the material reality of racist institutions and social practices. She believes, like Calvin and the contemporary Black theologian Reggie L. Williams, that each encounter with another person is an encounter with an image of God, in effect God himself, thus placing an immense weight on the treatment of others, surpassing even the Golden Rule. Even if a man is trying to kill you, “you owe him everything.” As Calvin does, she believes that each encounter with another person is a question that God is asking of you. In a recent lecture, she described one of God’s goals for creation—which, by implication, should be a human goal—as “human flourishing.” “Flourishing” is a startling word. Its pursuit demands far more than tolerance, or even civic equality: it demands a passionate devotion to others, regardless of your connections through family, country, race or religion. For her, good and evil are relational, social—not solely internal matters. Christianity, she has said, is an ethic, not an identity.

more here.

IN THE ANTIC TALE that opens The Cheerful Scapegoat, Wayne Koestenbaum’s book of self-described “fables,” a woman named Crocus, like the flower, arrives at a house party wearing a checkered frock designed by the Abstract Expressionist Adolph Gottlieb. She cowers in the entrance, vacillating over whether to enter or not. She phones her doctor, a man whom she refers to as the “miscreant-confessor,” who entreats her to be social. Inside, Crocus accompanies a “fashionable mortician” to a bedroom where she happens upon a fully clothed woman lying atop a fully clothed man. Observing something “unformed and infantile” about the man’s features, Crocus is overcome by a feeling of revulsion, “as if she were looking at a Chardin painting for the first time and were not comprehending her ecstasy—a conundrum which forced Crocus to shove her rapture into a different medicine-cabinet, a hiding-place christened ‘Disgust.’” From this point on, any attempt to pithily encapsulate what happens is doomed.

IN THE ANTIC TALE that opens The Cheerful Scapegoat, Wayne Koestenbaum’s book of self-described “fables,” a woman named Crocus, like the flower, arrives at a house party wearing a checkered frock designed by the Abstract Expressionist Adolph Gottlieb. She cowers in the entrance, vacillating over whether to enter or not. She phones her doctor, a man whom she refers to as the “miscreant-confessor,” who entreats her to be social. Inside, Crocus accompanies a “fashionable mortician” to a bedroom where she happens upon a fully clothed woman lying atop a fully clothed man. Observing something “unformed and infantile” about the man’s features, Crocus is overcome by a feeling of revulsion, “as if she were looking at a Chardin painting for the first time and were not comprehending her ecstasy—a conundrum which forced Crocus to shove her rapture into a different medicine-cabinet, a hiding-place christened ‘Disgust.’” From this point on, any attempt to pithily encapsulate what happens is doomed.

Most contemporary union drives are ultimately about the past—about the contrast that they draw between the more even prosperity of previous decades and the jarring inequalities of the present. But one that will culminate on Monday, the deadline for nearly six thousand

Most contemporary union drives are ultimately about the past—about the contrast that they draw between the more even prosperity of previous decades and the jarring inequalities of the present. But one that will culminate on Monday, the deadline for nearly six thousand  In January, French President Emmanuel Macron called the AstraZeneca–Oxford coronavirus vaccine “quasi-ineffective for people over 65”, on the day that the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended approving it. Kate Bingham, one of the architects of the UK vaccine-procurement programme, has since called the remarks “irresponsible”, because the vaccine has been recommended by regulators for use in people of all ages.

In January, French President Emmanuel Macron called the AstraZeneca–Oxford coronavirus vaccine “quasi-ineffective for people over 65”, on the day that the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended approving it. Kate Bingham, one of the architects of the UK vaccine-procurement programme, has since called the remarks “irresponsible”, because the vaccine has been recommended by regulators for use in people of all ages. Most of us think that knowledge starts with experience. You take yourself to know that you’re reading this article right now, and how do you know that? For starters, you might cite your visual experiences of looking at a screen, colourful experiences. And how do you get those? Well, sensory experiences come from our sensory organs and nervous system. From there, the mind might have to do some interpretative work to make sense of the sensory experiences, turning the lines and loops before you into letters, words and sentences. But you start from a kind of cognitive freebie: what’s ‘given’ to you in experience.

Most of us think that knowledge starts with experience. You take yourself to know that you’re reading this article right now, and how do you know that? For starters, you might cite your visual experiences of looking at a screen, colourful experiences. And how do you get those? Well, sensory experiences come from our sensory organs and nervous system. From there, the mind might have to do some interpretative work to make sense of the sensory experiences, turning the lines and loops before you into letters, words and sentences. But you start from a kind of cognitive freebie: what’s ‘given’ to you in experience. The experiment measures the decays of B-hadrons, particles containing bottom quarks. Quarks make up the protons and neutrons inside every atomic nucleus, but those are “up” and “down” quarks. The bottom quark is one of their cousins, and is much heavier.

The experiment measures the decays of B-hadrons, particles containing bottom quarks. Quarks make up the protons and neutrons inside every atomic nucleus, but those are “up” and “down” quarks. The bottom quark is one of their cousins, and is much heavier. On the day before the accident, Milad Salama could hardly contain his excitement for the kindergarten class trip. “Baba,” he said, addressing his father, Abed, “I want to buy food for the picnic tomorrow.” Abed took his five-and-a-half-year-old son to a nearby convenience store, buying him a bottle of the Israeli orange drink Tapuzina, a tube of Pringles, and a chocolate Kinder Egg, his favorite dessert.

On the day before the accident, Milad Salama could hardly contain his excitement for the kindergarten class trip. “Baba,” he said, addressing his father, Abed, “I want to buy food for the picnic tomorrow.” Abed took his five-and-a-half-year-old son to a nearby convenience store, buying him a bottle of the Israeli orange drink Tapuzina, a tube of Pringles, and a chocolate Kinder Egg, his favorite dessert. The presiding scientific genius of the Romantic age, when science had not yet been dispersed into specialties that rarely connect with one another, Alexander von Humboldt wanted to know everything, and came closer than any of his contemporaries to doing so. Except for Aristotle, no scientist before or since this German polymath can boast an intellect as universal in reach as his and as influential for the salient work of his time. His neglect today is unfortunate but instructive.

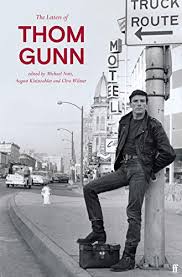

The presiding scientific genius of the Romantic age, when science had not yet been dispersed into specialties that rarely connect with one another, Alexander von Humboldt wanted to know everything, and came closer than any of his contemporaries to doing so. Except for Aristotle, no scientist before or since this German polymath can boast an intellect as universal in reach as his and as influential for the salient work of his time. His neglect today is unfortunate but instructive. Some of the rawest moments come in early letters to Mike Kitay, Gunn’s lifelong partner, whom he met in 1952 when they were both undergraduates at Cambridge and whom he followed to the USA when Kitay returned there in 1954, after which Gunn felt able to come out. ‘We can lead rich lives together if we allow each other to, my beloved,’ Gunn writes to him in 1961. ‘Oh baby, please settle for me. I’ll never be your ideal, but you’ll never find your ideal on earth.’ It’s a letter written over the course of a week, with headings marking out the different days; it ends, ‘I can’t go on like this much longer. Please, my darling Mike.’ Gunn was largely a writer of tight, syllabic poetry who aimed for a lack of ‘central personality’; the directness and freedom of expression in letters such as these offer us a side of him we rarely, if ever, have seen before. By contrast, a letter written a few months later to the Faber editor Charles Monteith sees Gunn retreating behind a mask of business, discussing what would become a well-known combined edition of his work and that of Ted Hughes, eventually published in 1962 (the footnote reveals, interestingly, that Larkin was also to be included in the project, but his publisher at the time, the Marvell Press, said no).

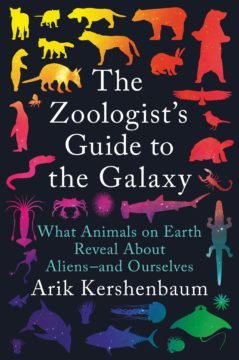

Some of the rawest moments come in early letters to Mike Kitay, Gunn’s lifelong partner, whom he met in 1952 when they were both undergraduates at Cambridge and whom he followed to the USA when Kitay returned there in 1954, after which Gunn felt able to come out. ‘We can lead rich lives together if we allow each other to, my beloved,’ Gunn writes to him in 1961. ‘Oh baby, please settle for me. I’ll never be your ideal, but you’ll never find your ideal on earth.’ It’s a letter written over the course of a week, with headings marking out the different days; it ends, ‘I can’t go on like this much longer. Please, my darling Mike.’ Gunn was largely a writer of tight, syllabic poetry who aimed for a lack of ‘central personality’; the directness and freedom of expression in letters such as these offer us a side of him we rarely, if ever, have seen before. By contrast, a letter written a few months later to the Faber editor Charles Monteith sees Gunn retreating behind a mask of business, discussing what would become a well-known combined edition of his work and that of Ted Hughes, eventually published in 1962 (the footnote reveals, interestingly, that Larkin was also to be included in the project, but his publisher at the time, the Marvell Press, said no). Is anybody else out there? For as long as humans have recognized Earth as but one planet in a vast, orb-speckled universe, we have pondered the mystery of extraterrestrial life. After Nicolaus Copernicus introduced heliocentric theory to 16th century Europe, astronomers began to dream about “other worlds” — and populate them with imaginary creatures. Pioneering astronomers such as Johannes Kepler (father of planetary motion) and William Herschel (discoverer of Uranus) believed in the existence of alien life. Peering through his telescope, Herschel thought he spied towns and forests on the lunar surface. We’re still looking. In 2017, a mysterious object named “Oumuamua” was observed

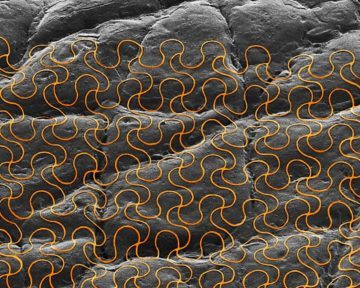

Is anybody else out there? For as long as humans have recognized Earth as but one planet in a vast, orb-speckled universe, we have pondered the mystery of extraterrestrial life. After Nicolaus Copernicus introduced heliocentric theory to 16th century Europe, astronomers began to dream about “other worlds” — and populate them with imaginary creatures. Pioneering astronomers such as Johannes Kepler (father of planetary motion) and William Herschel (discoverer of Uranus) believed in the existence of alien life. Peering through his telescope, Herschel thought he spied towns and forests on the lunar surface. We’re still looking. In 2017, a mysterious object named “Oumuamua” was observed  Materials scientists aren’t the first people you’d think would be pulled into the fight against COVID-19. But that’s what happened to John Rogers. He leads a team at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, that develops soft, flexible, skin-like materials with health-monitoring applications. One device, designed to sit in the hollow at the base of the throat, is a wireless, Bluetooth-connected piece of polymer and circuitry that provides real-time monitoring of talking, breathing, heart rate and other vital signs, which could be used in individuals who have had a stroke and require speech therapy

Materials scientists aren’t the first people you’d think would be pulled into the fight against COVID-19. But that’s what happened to John Rogers. He leads a team at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, that develops soft, flexible, skin-like materials with health-monitoring applications. One device, designed to sit in the hollow at the base of the throat, is a wireless, Bluetooth-connected piece of polymer and circuitry that provides real-time monitoring of talking, breathing, heart rate and other vital signs, which could be used in individuals who have had a stroke and require speech therapy At Vancouver’s University of British Columbia, the Brock Commons Tallwood House, sheathed in sleek blond wood, stands out among the neighboring gray concrete towers. This striking facade isn’t just an aesthetic choice. When it opened in 2017, the 18-story residence hall was the tallest building constructed of timber in the world. Erected from prefabricated components in just 70 days, it was faster and cheaper to build than a conventional building. What’s more, its material saved over 2,400 metric tons of carbon emissions.

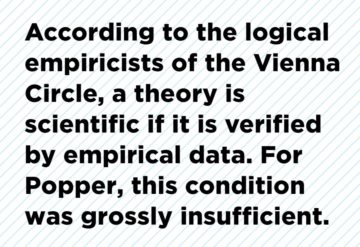

At Vancouver’s University of British Columbia, the Brock Commons Tallwood House, sheathed in sleek blond wood, stands out among the neighboring gray concrete towers. This striking facade isn’t just an aesthetic choice. When it opened in 2017, the 18-story residence hall was the tallest building constructed of timber in the world. Erected from prefabricated components in just 70 days, it was faster and cheaper to build than a conventional building. What’s more, its material saved over 2,400 metric tons of carbon emissions. This is the “demarcation problem,” as the Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper famously called it. The solution is not at all obvious. You cannot just rely on those parts of science that are correct, since science is a work in progress. Much of what scientists claim is provisional, after all, and often turns out to be wrong. That does not mean those who were wrong were engaged in “pseudoscience,” or even that they were doing “bad science”—this is just how science operates. What makes a theory scientific is something other than the fact that it is right.

This is the “demarcation problem,” as the Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper famously called it. The solution is not at all obvious. You cannot just rely on those parts of science that are correct, since science is a work in progress. Much of what scientists claim is provisional, after all, and often turns out to be wrong. That does not mean those who were wrong were engaged in “pseudoscience,” or even that they were doing “bad science”—this is just how science operates. What makes a theory scientific is something other than the fact that it is right. In Muslim communities, homosexuality is intrinsically linked to anxiety, intimidation, violence, and, in some cases, death. For many, it involves living a closeted existence for fear of being ostracised or disowned. Islamic theological teachings, disseminated by religious institutions and espoused by community leaders, range from preaching for our execution to advising us to live a life of celibacy. Yet voices on the left, historically a stronghold of LGBTI support, do not sufficiently decry the abysmal treatment of gay and bi people of Muslim heritage, nor do they adequately mobilize against this specific and brutal form of homophobia.

In Muslim communities, homosexuality is intrinsically linked to anxiety, intimidation, violence, and, in some cases, death. For many, it involves living a closeted existence for fear of being ostracised or disowned. Islamic theological teachings, disseminated by religious institutions and espoused by community leaders, range from preaching for our execution to advising us to live a life of celibacy. Yet voices on the left, historically a stronghold of LGBTI support, do not sufficiently decry the abysmal treatment of gay and bi people of Muslim heritage, nor do they adequately mobilize against this specific and brutal form of homophobia.