David Masciotra in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

David Masciotra in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

DAVID MASCIOTRA: Did your and Marv Waterstone’s decision to publish the lectures from your course “What Is Politics?” derive from a sense of needing to return to fundamentals, perhaps due to the convergence of crises we are currently experiencing?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Marv and I felt that the content of the book, which does begin with essentials, like the nature of presupposed “common sense” — where people get their ideas and beliefs from — goes on to reach things that are very urgent and critical today. We based this on our own sense of things, and the reactions from the two class cohorts. One is undergraduate students at the University of Arizona, and the other is community people, older people. The two groups interact, and judging from their reactions, both seemed to find it valuable and instructive. That was encouragement enough for us to put it together, and there is material that goes beyond the lectures, of course. It seemed worth doing, and the reactions we’ve had so far reinforce that conclusion.

What do you believe is a prevalent misconception among Americans in answer to the simple question “What is politics?” And how would you correct that misconception?

Well, if this course was taught by a mainstream instructor, politics would be what is taught in a civics course: how the rules are in the Senate and House, who introduces legislation, who votes on it, the nuts and bolts of the workings of the formal political system. From our point of view, politics is what happens in the streets and what happens in corporate boardrooms. The latter overwhelmingly dominates the shaping and framing of what happens in the political system.

More here.

Corey Robin in the NYRB:

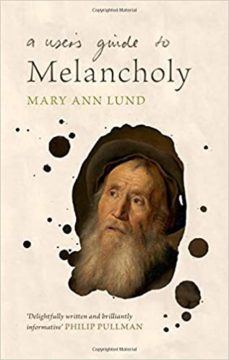

Corey Robin in the NYRB: Mary Ann Lund’s book serves as an introduction not just to Burton’s magnum opus but to contemporary and historical conceptions of melancholy. Do not make the mistake of confusing “melancholy” with what we now call depression. Her brief is not so much to say why or how Burton’s style is so delightful but to give us a learned, broad and readable picture of Renaissance medicine, using Burton’s book as a starting point. Melancholy, in the early modern world, could present itself in bizarre ways. Think “Embarrassing Early Modern European Bodies”. She tells, for instance, the story of the classical scholar Isaac Casaubon (1559-1614), whose “postmortem revealed that his bladder was malformed and that the supplementary bladder was nearly six times as large as the main chamber”. The apparent reason was that he had regularly ignored the call of nature while being absorbed in his work. (That George Eliot chose the name for the dry-as-dust obsessive in

Mary Ann Lund’s book serves as an introduction not just to Burton’s magnum opus but to contemporary and historical conceptions of melancholy. Do not make the mistake of confusing “melancholy” with what we now call depression. Her brief is not so much to say why or how Burton’s style is so delightful but to give us a learned, broad and readable picture of Renaissance medicine, using Burton’s book as a starting point. Melancholy, in the early modern world, could present itself in bizarre ways. Think “Embarrassing Early Modern European Bodies”. She tells, for instance, the story of the classical scholar Isaac Casaubon (1559-1614), whose “postmortem revealed that his bladder was malformed and that the supplementary bladder was nearly six times as large as the main chamber”. The apparent reason was that he had regularly ignored the call of nature while being absorbed in his work. (That George Eliot chose the name for the dry-as-dust obsessive in  Although they inspired many imitators, the Fox sisters did not number among those mediums who subsequently developed Spiritualism as an organized movement in both the United States and Britain. Their ranks included Emma Hardinge Britten, who wrote its history and traveled the public lecture circuit as a trance medium in the late 1850s, delivering opinions about the issues of the day as dictated by the spirits. By contrast, Victoria Woodhull had cut her ties to Spiritualist groups when her claim to clairvoyant powers persuaded the tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt to back her in founding the first female brokerage firm on Wall Street. But shortly thereafter she managed to recruit both Spiritualist and women’s rights organizations to support her bid for the presidency in 1872. Meanwhile in Britain, Georgina Weldon — not a medium herself but a stage-struck Spiritualist — fought the efforts of her husband and his squad of doctors to commit her to an asylum. She challenged Britain’s lunacy laws with more than a decade of agitation, which included parading sandwich-board men as pickets, scattering leaflets from a hot-air balloon, giving theatrical performances and offering antic testimony in court.

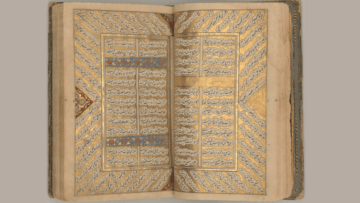

Although they inspired many imitators, the Fox sisters did not number among those mediums who subsequently developed Spiritualism as an organized movement in both the United States and Britain. Their ranks included Emma Hardinge Britten, who wrote its history and traveled the public lecture circuit as a trance medium in the late 1850s, delivering opinions about the issues of the day as dictated by the spirits. By contrast, Victoria Woodhull had cut her ties to Spiritualist groups when her claim to clairvoyant powers persuaded the tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt to back her in founding the first female brokerage firm on Wall Street. But shortly thereafter she managed to recruit both Spiritualist and women’s rights organizations to support her bid for the presidency in 1872. Meanwhile in Britain, Georgina Weldon — not a medium herself but a stage-struck Spiritualist — fought the efforts of her husband and his squad of doctors to commit her to an asylum. She challenged Britain’s lunacy laws with more than a decade of agitation, which included parading sandwich-board men as pickets, scattering leaflets from a hot-air balloon, giving theatrical performances and offering antic testimony in court. For the past year, I’ve been researching and studying the works of Hafez, one of Iran’s most beloved and influential poets. More than 600 years after his death, his work is still invoked regularly, quoted by Iranian politicians to skewer their rivals and by everyday Iranians in casual conversations over dinner. Normally, this is the part where I would share a verse of his work, or tell you how complex and beautiful his words are. I would to tell you how Iranians use his poems as a form of divination, like a tarot card reading of sorts. Instead, I am consumed with trying to understand why I’ve been devoting so much time to studying the verses of a poet from the fourteenth century right now, when my country is going through every imaginable version of pain. Wouldn’t it make more sense to focus on current national security issues instead of diving into the art of our past?

For the past year, I’ve been researching and studying the works of Hafez, one of Iran’s most beloved and influential poets. More than 600 years after his death, his work is still invoked regularly, quoted by Iranian politicians to skewer their rivals and by everyday Iranians in casual conversations over dinner. Normally, this is the part where I would share a verse of his work, or tell you how complex and beautiful his words are. I would to tell you how Iranians use his poems as a form of divination, like a tarot card reading of sorts. Instead, I am consumed with trying to understand why I’ve been devoting so much time to studying the verses of a poet from the fourteenth century right now, when my country is going through every imaginable version of pain. Wouldn’t it make more sense to focus on current national security issues instead of diving into the art of our past? Early this spring, wary and disoriented despite the vaccine at work in my system, I sought a book to help me navigate the strange, bardo-like moment in which disaster and its aftermath begin to overlap. “To the Lighthouse,” Virginia Woolf’s 1927 masterpiece, was the one that kept coming to mind — specifically its experimental middle section, “Time Passes.” Parsed into 10 “chapters,” with its swirling rhythms, involuted structure and flights into abstraction, “Time Passes” presents an especial challenge to the pre-post-pandemic brain. I hoped to find in Woolf’s evocation of grief as a disruption of one’s sense of time not a solution but the solace of a riddle’s key connections laid bare.

Early this spring, wary and disoriented despite the vaccine at work in my system, I sought a book to help me navigate the strange, bardo-like moment in which disaster and its aftermath begin to overlap. “To the Lighthouse,” Virginia Woolf’s 1927 masterpiece, was the one that kept coming to mind — specifically its experimental middle section, “Time Passes.” Parsed into 10 “chapters,” with its swirling rhythms, involuted structure and flights into abstraction, “Time Passes” presents an especial challenge to the pre-post-pandemic brain. I hoped to find in Woolf’s evocation of grief as a disruption of one’s sense of time not a solution but the solace of a riddle’s key connections laid bare. Stockton, California has gotten

Stockton, California has gotten

On February 2, 1977, Palestinian poet Rashid Hussein died in his New York apartment. Hussein had been born forty-one years earlier in Musmus, a town not far from Nazareth. Politics for Hussein, Edward Said remembered, “lost its impersonality and its cruel demagogic spirit.” Hussein, Said wrote of his dear friend, “simply asked that you remember the search for real answers, and never give it up, never be seduced by mere arrangements.” Sharply critical of his own society and its rulers—he had a map of the Middle East on his wall with “thought forbidden here” scrawled across it in Arabic—Hussein was also a partisan of the Third World. “I am from Asia,” he pronounced in an early poem, “The land of fire / Forging furnace of freedom-fighters.”

On February 2, 1977, Palestinian poet Rashid Hussein died in his New York apartment. Hussein had been born forty-one years earlier in Musmus, a town not far from Nazareth. Politics for Hussein, Edward Said remembered, “lost its impersonality and its cruel demagogic spirit.” Hussein, Said wrote of his dear friend, “simply asked that you remember the search for real answers, and never give it up, never be seduced by mere arrangements.” Sharply critical of his own society and its rulers—he had a map of the Middle East on his wall with “thought forbidden here” scrawled across it in Arabic—Hussein was also a partisan of the Third World. “I am from Asia,” he pronounced in an early poem, “The land of fire / Forging furnace of freedom-fighters.” Alice Rohrwacher’s most recent full-length feature,

Alice Rohrwacher’s most recent full-length feature,  One of The Free World’s larger themes is the replacement of Paris by New York as “the capital of the modern.” For nearly a century, Menand writes, “Paris was where advanced Western culture—especially painting, sculpture, literature, dance, film, and photography, but also fashion, cuisine, and sexual mores—was . . . created, accredited, and transmitted.” It was not the Nazi occupation that changed things; Paris got off lightly compared with other occupied capitals. (Though it would have been burned to the ground if the German commandant had not ignored Hitler’s orders.) And immediately after the Liberation in 1944, there was a cultural efflorescence. Existentialism was in vogue everywhere; its three main exponents—Sartre, Camus, and Beauvoir—were international celebrities. But the compass needle was turning: as Sartre acknowledged, “the greatest literary development in France between 1929 and 1939 was the discovery of Faulkner, Dos Passos, Hemingway, Caldwell, Steinbeck.” American leadership in painting was even more pronounced in the 1940s and 50s. Paris would always retain its aura, particularly for Black American writers and musicians, though not only for them—Paris would play a large part in liberating Susan Sontag, for example. But American global primacy was so complete in the fifties and sixties that the cultural primacy of its capital city could not be gainsaid.

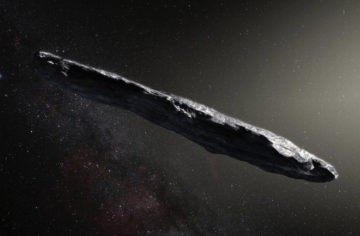

One of The Free World’s larger themes is the replacement of Paris by New York as “the capital of the modern.” For nearly a century, Menand writes, “Paris was where advanced Western culture—especially painting, sculpture, literature, dance, film, and photography, but also fashion, cuisine, and sexual mores—was . . . created, accredited, and transmitted.” It was not the Nazi occupation that changed things; Paris got off lightly compared with other occupied capitals. (Though it would have been burned to the ground if the German commandant had not ignored Hitler’s orders.) And immediately after the Liberation in 1944, there was a cultural efflorescence. Existentialism was in vogue everywhere; its three main exponents—Sartre, Camus, and Beauvoir—were international celebrities. But the compass needle was turning: as Sartre acknowledged, “the greatest literary development in France between 1929 and 1939 was the discovery of Faulkner, Dos Passos, Hemingway, Caldwell, Steinbeck.” American leadership in painting was even more pronounced in the 1940s and 50s. Paris would always retain its aura, particularly for Black American writers and musicians, though not only for them—Paris would play a large part in liberating Susan Sontag, for example. But American global primacy was so complete in the fifties and sixties that the cultural primacy of its capital city could not be gainsaid. Life, for all its complexities, has a simple commonality: It spreads. Plants, animals and bacteria have colonized almost every nook and cranny of our world.

Life, for all its complexities, has a simple commonality: It spreads. Plants, animals and bacteria have colonized almost every nook and cranny of our world.  I celebrated my second pandemic birthday recently. Many things were weird about it: opening presents on Zoom, my phone’s insistent photo reminders from “one year ago today” that could be mistaken for last month, my partner brightly wishing me “iki domuz,” a Turkish phrase that literally means “two pigs.” Well, that last one is actually quite normal in our house. Long ago, I took my first steps into adult language lessons and tried to impress my Turkish American boyfriend on his special day. My younger self nervously bungled through new vocabulary—The numbers! The animals! The months!—to wish him “iki domuz” instead of “happy birthday” (İyi ki doğdun) while we drank like pigs in his tiny apartment outside of UCLA. Now, more than a decade later, that slipup is immortalized as our own peculiar greeting to each other twice a year.

I celebrated my second pandemic birthday recently. Many things were weird about it: opening presents on Zoom, my phone’s insistent photo reminders from “one year ago today” that could be mistaken for last month, my partner brightly wishing me “iki domuz,” a Turkish phrase that literally means “two pigs.” Well, that last one is actually quite normal in our house. Long ago, I took my first steps into adult language lessons and tried to impress my Turkish American boyfriend on his special day. My younger self nervously bungled through new vocabulary—The numbers! The animals! The months!—to wish him “iki domuz” instead of “happy birthday” (İyi ki doğdun) while we drank like pigs in his tiny apartment outside of UCLA. Now, more than a decade later, that slipup is immortalized as our own peculiar greeting to each other twice a year.

Climate change, a pandemic or the coordinated activity of neurons in the brain: In all of these examples, a transition takes place at a certain point from the base state to a new state. Researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have discovered a universal mathematical structure at these so-called tipping points. It creates the basis for a better understanding of the behavior of networked systems.

Climate change, a pandemic or the coordinated activity of neurons in the brain: In all of these examples, a transition takes place at a certain point from the base state to a new state. Researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have discovered a universal mathematical structure at these so-called tipping points. It creates the basis for a better understanding of the behavior of networked systems.