Matthew Gannon and Wilson Taylor in The Tribune:

Matthew Gannon and Wilson Taylor in The Tribune:

Kurt Vonnegut died 14 years ago today. A few weeks beforehand, he had been taking his dog for a walk and got tangled up in the leash. The 84-year-old American fabulist fell and hit his head on the sidewalk outside his midtown Manhattan brownstone, slipping into a coma that he never came out of. So it goes, the late author might have said.

‘So it goes’ is the characteristically resigned phrase that recurs throughout Vonnegut’s bleakly witty and moving 1969 novel Slaughterhouse-Five. In marking the anniversary of his death, we might also remember another line from that work, which includes time travel and aliens and the real story of Vonnegut’s time as a prisoner of the Nazis during the 1945 Allied firebombing of Dresden: ‘When a person dies he only appears to die.’

This is something the novel’s protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, learns from the Tralfamadorians, an extraterrestrial species that experiences time all at once rather than sequentially. Even if someone is dead now, they tell Billy, ‘he is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at his funeral.’

It’s a comforting idea of sorts. ‘When a Tralfamadorian sees a corpse,’ Billy explains, ‘all he thinks is that the dead person is in bad condition in that particular moment, but that the same person is just fine in plenty of other moments.’

Billy Pilgrim becomes ‘unstuck in time’ in Slaughterhouse-Five, and he is unexpectedly dragged from one moment to another—even before his birth and after his death—by some unknown power. He’s an old man one minute and a baby the next. He never knows when he’ll be, and without warning he can be brought back to that firebombing that Vonnegut himself only survived because he and the rest of the prisoners of war sheltered in the basement of an abandoned slaughterhouse.

More here.

Bell performed his project of, to use Hussey’s subtitle, “making modernism” chiefly through the championing of “modern art”. By this he meant painting that eschewed anecdote, nostalgia or moral messaging in favour of lines and colours combined to stir the aesthetic sense. For ease of reference, he called the thing he was after “significant form”. While sensible Britain saw cubism, together with post-impressionism, as incoherent and formless to the point of lunacy, Bell followed the example of the older and more expert critic Roger Fry in reframing these movements as heroic attempts to purge the plastic arts of any lingering attachment to representational fidelity. His great touchstones were French (he called Paul Cézanne “the great Christopher Columbus of a new continent of form”) but admitted that occasionally you found an English painter who was making the right shapes – Vanessa Bell, say, or Duncan Grant. The fact that Vanessa was his wife and Duncan her lover detracted only slightly from his pronouncements.

Bell performed his project of, to use Hussey’s subtitle, “making modernism” chiefly through the championing of “modern art”. By this he meant painting that eschewed anecdote, nostalgia or moral messaging in favour of lines and colours combined to stir the aesthetic sense. For ease of reference, he called the thing he was after “significant form”. While sensible Britain saw cubism, together with post-impressionism, as incoherent and formless to the point of lunacy, Bell followed the example of the older and more expert critic Roger Fry in reframing these movements as heroic attempts to purge the plastic arts of any lingering attachment to representational fidelity. His great touchstones were French (he called Paul Cézanne “the great Christopher Columbus of a new continent of form”) but admitted that occasionally you found an English painter who was making the right shapes – Vanessa Bell, say, or Duncan Grant. The fact that Vanessa was his wife and Duncan her lover detracted only slightly from his pronouncements. As a titan of the Renaissance, Dürer needs no puffing up, but Hoare doesn’t stint on the claims: “No one painted dirt before Dürer,” is a particularly arresting example. He created “the first self-portrait of an artist painted for its own sake.” In

As a titan of the Renaissance, Dürer needs no puffing up, but Hoare doesn’t stint on the claims: “No one painted dirt before Dürer,” is a particularly arresting example. He created “the first self-portrait of an artist painted for its own sake.” In  “Y

“Y When Nina Totenberg was a young reporter hustling for bylines in the 1960s, she pitched a story about how college women were procuring the birth control pill. “Nina, are you a virgin?” her male editor responded. “I can’t let you do this.” Such were the obstacles that Totenberg and the women journalists of her generation faced, largely relegated to the frivolous “women’s pages” and denied the chance to cover so-called hard news. But as Lisa Napoli’s “Susan, Linda, Nina & Cokie” chronicles, just as some women journalists were suing Newsweek and The New York Times over gender discrimination, in the 1970s, an upstart nonprofit called National Public Radio arrived on the scene offering new opportunities.

When Nina Totenberg was a young reporter hustling for bylines in the 1960s, she pitched a story about how college women were procuring the birth control pill. “Nina, are you a virgin?” her male editor responded. “I can’t let you do this.” Such were the obstacles that Totenberg and the women journalists of her generation faced, largely relegated to the frivolous “women’s pages” and denied the chance to cover so-called hard news. But as Lisa Napoli’s “Susan, Linda, Nina & Cokie” chronicles, just as some women journalists were suing Newsweek and The New York Times over gender discrimination, in the 1970s, an upstart nonprofit called National Public Radio arrived on the scene offering new opportunities. How did one of the greatest philosophers who ever lived get so much wrong? David Hume certainly deserves his place in the philosophers’ pantheon, but when it comes to politics, he erred time and again. The 18th-century giant of the Scottish Enlightenment was sceptical of democracy and—despite his reputation as “the great infidel”—in favour of an established church. He was iffy on the equality of women and notoriously racist. He took part in a pointless military raid on France without publicly questioning its legitimacy.

How did one of the greatest philosophers who ever lived get so much wrong? David Hume certainly deserves his place in the philosophers’ pantheon, but when it comes to politics, he erred time and again. The 18th-century giant of the Scottish Enlightenment was sceptical of democracy and—despite his reputation as “the great infidel”—in favour of an established church. He was iffy on the equality of women and notoriously racist. He took part in a pointless military raid on France without publicly questioning its legitimacy. The story of the placebo effect used to be simple: When people don’t know they are taking sugar pills or think they might be a real treatment, the pills can work. It’s a foundational idea in medicine and in clinical drug trials

The story of the placebo effect used to be simple: When people don’t know they are taking sugar pills or think they might be a real treatment, the pills can work. It’s a foundational idea in medicine and in clinical drug trials  The economist Branko Milanovic has been a central participant in the debates of this emerging field, as well as one of its most idiosyncratic contributors. Born in Belgrade when it was part of Yugoslavia, Milanovic wrote his dissertation on income inequality in his home country long before it was a fashionable topic. He went on to research income inequality as an economist at the World Bank for nearly two decades before taking up a string of academic appointments; he currently teaches at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. But he is not your typical World Bank economist: Milanovic knows his Marx and, though not a Marxist himself, has long insisted on the value of class analysis and historical perspectives to economics, while also dabbling in political-philosophy debates about distributive justice. His experience of life under actually existing socialism, meanwhile, gave him critical distance from the end-of-history narratives that were trumpeted in much of the West after the fall of the USSR—as well as from the end-of-the-end-of-history hand-wringing that has proliferated since 2016. The discourse, then, seems to be catching up to where Milanovic has been all along.

The economist Branko Milanovic has been a central participant in the debates of this emerging field, as well as one of its most idiosyncratic contributors. Born in Belgrade when it was part of Yugoslavia, Milanovic wrote his dissertation on income inequality in his home country long before it was a fashionable topic. He went on to research income inequality as an economist at the World Bank for nearly two decades before taking up a string of academic appointments; he currently teaches at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. But he is not your typical World Bank economist: Milanovic knows his Marx and, though not a Marxist himself, has long insisted on the value of class analysis and historical perspectives to economics, while also dabbling in political-philosophy debates about distributive justice. His experience of life under actually existing socialism, meanwhile, gave him critical distance from the end-of-history narratives that were trumpeted in much of the West after the fall of the USSR—as well as from the end-of-the-end-of-history hand-wringing that has proliferated since 2016. The discourse, then, seems to be catching up to where Milanovic has been all along. To apply Claude Lévi-Strauss’s structural anthropology, a crush is called a crush because it crushes you. A crush is distinct from friendship or love by dint of its intensity and sudden onset. It is marked by passionate feeling, by constant daydreaming: a crush exists in the dreamy space between fantasy and regular life. The objects of our crushes, who themselves may also be referred to as crushes, cannot be figures central to our daily lives. They appear on the periphery of our days, made romantic by their distance.

To apply Claude Lévi-Strauss’s structural anthropology, a crush is called a crush because it crushes you. A crush is distinct from friendship or love by dint of its intensity and sudden onset. It is marked by passionate feeling, by constant daydreaming: a crush exists in the dreamy space between fantasy and regular life. The objects of our crushes, who themselves may also be referred to as crushes, cannot be figures central to our daily lives. They appear on the periphery of our days, made romantic by their distance. Aladdin, readers are sometimes surprised to learn, is a boy from China. Yet the text is ambivalent about what this means, and pokes gentle fun at the idea of cultural authenticity. Scheherazade has hardly begun her tale when she forgets quite where it is set. “Majesty, in the capital of one of China’s vast and wealthy kingdoms, whose name escapes me at present, there lived a tailor named Mustafa.” The story’s institutions are Ottoman, the customs half-invented, the palace redolent of Versailles. It is a mishmash and knows it.

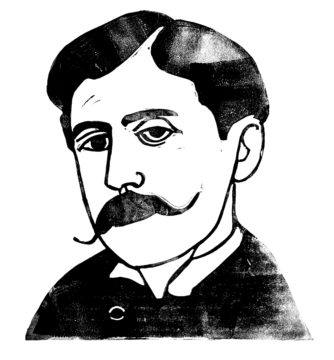

Aladdin, readers are sometimes surprised to learn, is a boy from China. Yet the text is ambivalent about what this means, and pokes gentle fun at the idea of cultural authenticity. Scheherazade has hardly begun her tale when she forgets quite where it is set. “Majesty, in the capital of one of China’s vast and wealthy kingdoms, whose name escapes me at present, there lived a tailor named Mustafa.” The story’s institutions are Ottoman, the customs half-invented, the palace redolent of Versailles. It is a mishmash and knows it. When the first volume of “In Search of Lost Time” appeared, a year before the Great War, the shock of its excellence was captured in a delicious exchange with André Gide, the magus of the Parisian literary scene. Apologizing for having passed on “Swann’s Way” for his Nouvelle Revue Française, Gide offered an explanation almost more insulting than the original rejection: “For me you were still the man who frequented the houses of Mmes X. and Z., the man who wrote for the Figaro. I thought of you, shall I confess it, as ‘du côté de chez Verdurin’; a snob, a man of the world, and a dilettante—the worst possible thing for our review.” Proust, who had money, had offered to help subsidize the publication, which, Gide fumbles to explain, only made it seem a dubious effort at buying a reputation. (That year, Gide confided in his journal his doubts that any Jewish writer could truly master the “virtues” of the French tradition.)

When the first volume of “In Search of Lost Time” appeared, a year before the Great War, the shock of its excellence was captured in a delicious exchange with André Gide, the magus of the Parisian literary scene. Apologizing for having passed on “Swann’s Way” for his Nouvelle Revue Française, Gide offered an explanation almost more insulting than the original rejection: “For me you were still the man who frequented the houses of Mmes X. and Z., the man who wrote for the Figaro. I thought of you, shall I confess it, as ‘du côté de chez Verdurin’; a snob, a man of the world, and a dilettante—the worst possible thing for our review.” Proust, who had money, had offered to help subsidize the publication, which, Gide fumbles to explain, only made it seem a dubious effort at buying a reputation. (That year, Gide confided in his journal his doubts that any Jewish writer could truly master the “virtues” of the French tradition.) Usain Bolt won the men’s 100 metre final in the 2016 Olympic Games in 9.81 seconds and 42 strides. A few days later, Eliud Kipchoge ran 42 kilometres in 2 hours and 8 minutes to win the marathon. These extraordinary feats pose very different challenges for the human body, but the races began in much the same way. As the starting pistol fired, Bolt and Kipchoge began to use creatine phosphate, an energy-rich molecule stored in muscle tissue, to generate the energy-carrying molecule ATP. In a few seconds, however, both athletes’ stores of creatine phosphate were depleted, forcing their bodies to break down glucose to provide ATP to contracting muscle cells for a few more minutes. For Bolt and his fellow sprinters, a few minutes seems like an age. But for marathon runners, there is much farther to go. To reach the finish line, these endurance athletes rely on a slower, but more efficient way to generate ATP that uses oxygen to burn fats and carbohydrates, in structures inside the cell called mitochondria.

Usain Bolt won the men’s 100 metre final in the 2016 Olympic Games in 9.81 seconds and 42 strides. A few days later, Eliud Kipchoge ran 42 kilometres in 2 hours and 8 minutes to win the marathon. These extraordinary feats pose very different challenges for the human body, but the races began in much the same way. As the starting pistol fired, Bolt and Kipchoge began to use creatine phosphate, an energy-rich molecule stored in muscle tissue, to generate the energy-carrying molecule ATP. In a few seconds, however, both athletes’ stores of creatine phosphate were depleted, forcing their bodies to break down glucose to provide ATP to contracting muscle cells for a few more minutes. For Bolt and his fellow sprinters, a few minutes seems like an age. But for marathon runners, there is much farther to go. To reach the finish line, these endurance athletes rely on a slower, but more efficient way to generate ATP that uses oxygen to burn fats and carbohydrates, in structures inside the cell called mitochondria. Early in 2016, not long after the inauguration of Donald Trump as President of the United States, an artist named Arthur Jafa screened a work of video art at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York City. The video was titled Love is the message, the message is death. It is about seven minutes long. It is constructed of found footage ranging in time from the immediate present to shaky clips from the early days of film. Most of the clips are just a couple of seconds long. Generally, they feature Black people, African Americans in specific. Much of the footage is upsetting. That’s to say, there are clips of police brutality against Black people. These clips are interspersed with other images not obviously related to the specific issue of police mistreatment of African Americans. The entire video is set to the music of Kanye West’s gospel-ish song Ultralight Beam.

Early in 2016, not long after the inauguration of Donald Trump as President of the United States, an artist named Arthur Jafa screened a work of video art at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York City. The video was titled Love is the message, the message is death. It is about seven minutes long. It is constructed of found footage ranging in time from the immediate present to shaky clips from the early days of film. Most of the clips are just a couple of seconds long. Generally, they feature Black people, African Americans in specific. Much of the footage is upsetting. That’s to say, there are clips of police brutality against Black people. These clips are interspersed with other images not obviously related to the specific issue of police mistreatment of African Americans. The entire video is set to the music of Kanye West’s gospel-ish song Ultralight Beam. When you hit “send” on a text message, it is easy to imagine that the note will travel directly from your phone to your friend’s. In fact, it typically goes on a long journey through a cellular network or the Internet, both of which rely on centralized infrastructure that can be damaged by natural disasters or shut down by repressive governments. For fear of state surveillance or interference, tech-savvy protesters in Hong Kong avoided the Internet by using software such as FireChat and Bridgefy to send messages directly between nearby phones.

When you hit “send” on a text message, it is easy to imagine that the note will travel directly from your phone to your friend’s. In fact, it typically goes on a long journey through a cellular network or the Internet, both of which rely on centralized infrastructure that can be damaged by natural disasters or shut down by repressive governments. For fear of state surveillance or interference, tech-savvy protesters in Hong Kong avoided the Internet by using software such as FireChat and Bridgefy to send messages directly between nearby phones.