Category: Archives

Psychology, Misinformation, and the Public Square

Teresa Carr in Undark:

One idle Saturday afternoon I wreaked havoc on the virtual town of Harmony Square, “a green and pleasant place,” according to its founders, famous for its pond swan, living statue, and Pineapple Pizza Festival. Using a fake news site called Megaphone — tagged with the slogan “everything louder than everything else” — and an army of bots, I ginned up outrage and divided the citizenry. In the end, Harmony Square was in shambles.

One idle Saturday afternoon I wreaked havoc on the virtual town of Harmony Square, “a green and pleasant place,” according to its founders, famous for its pond swan, living statue, and Pineapple Pizza Festival. Using a fake news site called Megaphone — tagged with the slogan “everything louder than everything else” — and an army of bots, I ginned up outrage and divided the citizenry. In the end, Harmony Square was in shambles.

I thoroughly enjoyed my 10 minutes of villainy — even laughed outright a few times. And that was the point. My beleaguered town is the center of the action for the online game Breaking Harmony Square, a collaboration between the U.S. Departments of State and Homeland Security, psychologists at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, and DROG, a Dutch initiative that uses gaming and education to fight misinformation. In my role as Chief Disinformation Officer of Harmony Square, I learned about the manipulation techniques people use to gain a following, foment discord, and then exploit societal tensions for political purposes.

More here.

Barbara Hepworth – Figures in a Landscape (1953)

The Unintended Beauty of Disaster

Adrian Searle at The Guardian:

Akomfrah plays fast and loose with time and place, the real and the constructed, to make larger, more complex narratives. A second three-screen video, Triptych, set in an unnamed location, is a panoply of street portraits. The title is taken from a track by jazz drummer and composer Max Roach, from his 1960 album We Insist! Roach’s wonderful Triptych: Prayer, Protest, Peace, which provides the soundtrack, with singer Abbey Lincoln keening and wailing wordlessly as Akomfrah’s camera glides and pauses. Practitioners of Candomblé, transgender people and queers of all sorts, street musicians, sassy kids and game old ladies, families, friends and passersby pose and smile for Akomfrah’s camera. Towards the end, we see an overhead shot of a vast portrait commemorating Breonna Taylor (shot dead by US police in her home in March last year), covering two basketball courts in Annapolis, Maryland.

Akomfrah plays fast and loose with time and place, the real and the constructed, to make larger, more complex narratives. A second three-screen video, Triptych, set in an unnamed location, is a panoply of street portraits. The title is taken from a track by jazz drummer and composer Max Roach, from his 1960 album We Insist! Roach’s wonderful Triptych: Prayer, Protest, Peace, which provides the soundtrack, with singer Abbey Lincoln keening and wailing wordlessly as Akomfrah’s camera glides and pauses. Practitioners of Candomblé, transgender people and queers of all sorts, street musicians, sassy kids and game old ladies, families, friends and passersby pose and smile for Akomfrah’s camera. Towards the end, we see an overhead shot of a vast portrait commemorating Breonna Taylor (shot dead by US police in her home in March last year), covering two basketball courts in Annapolis, Maryland.

more here.

Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life

Tanya Harrod at Literary Review:

Barbara Hepworth’s life was by any standard a remarkable one. It was a triumph of determination. She did not come from a deprived background: her father was a civil engineer who became a well-respected county surveyor for the West Riding of Yorkshire. She went to a good school and was exceptionally gifted musically. She wrote with great clarity and was an accomplished draughtswoman. She sailed into Leeds School of Art and in 1921 won a senior scholarship to the Royal College of Art, then under the invigorating leadership of the recently appointed William Rothenstein. At the college, which at the time occupied a building attached to the Victoria and Albert Museum, she chose to concentrate on sculpture, drawing from casts, modelling in clay, carving reliefs in plaster, with some stone and wood carving too. It was a traditional education, undertaken alongside another student from Yorkshire, Henry Moore.

Barbara Hepworth’s life was by any standard a remarkable one. It was a triumph of determination. She did not come from a deprived background: her father was a civil engineer who became a well-respected county surveyor for the West Riding of Yorkshire. She went to a good school and was exceptionally gifted musically. She wrote with great clarity and was an accomplished draughtswoman. She sailed into Leeds School of Art and in 1921 won a senior scholarship to the Royal College of Art, then under the invigorating leadership of the recently appointed William Rothenstein. At the college, which at the time occupied a building attached to the Victoria and Albert Museum, she chose to concentrate on sculpture, drawing from casts, modelling in clay, carving reliefs in plaster, with some stone and wood carving too. It was a traditional education, undertaken alongside another student from Yorkshire, Henry Moore.

more here.

Tuesday Poem

Something Invisible

Once I asked my master

“What is the difference

Between you and me?”

And he replied,

“Hafiz, only this:

If a herd of wild buffalo

Broke into our house

And knocked over

Our empty begging bowls,

Not a drop would spill from yours.

But there is Something Invisible

That God has placed in mine.

If That spilled from my bowl,

It could drown this whole world.”

by Hafiz

from I Heard God Laughing

Penguin Books, 2006

Renderings of Hafiz by Danliel Ladinsky

‘Mother Trees’ Are Intelligent: They Learn and Remember

Richard Schiffman in Scientific American:

Few researchers have had the pop culture impact of Suzanne Simard. The University of British Columbia ecologist was the model for Patricia Westerford, a controversial tree scientist in Richard Powers’s 2019 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Overstory. Simard’s work also inspired James Cameron’s vision of the godlike “Tree of Souls” in his 2009 box office hit Avatar. And her research was prominently featured in German forester Peter Wohlleben’s 2016 nonfiction bestseller The Hidden Life of Trees.

Few researchers have had the pop culture impact of Suzanne Simard. The University of British Columbia ecologist was the model for Patricia Westerford, a controversial tree scientist in Richard Powers’s 2019 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Overstory. Simard’s work also inspired James Cameron’s vision of the godlike “Tree of Souls” in his 2009 box office hit Avatar. And her research was prominently featured in German forester Peter Wohlleben’s 2016 nonfiction bestseller The Hidden Life of Trees.

What captured the public’s imagination was Simard’s findings that trees are social beings that exchange nutrients, help one another and communicate about insect pests and other environmental threats. Previous ecologists had focused on what happens aboveground, but Simard used radioactive isotopes of carbon to trace how trees share resources and information with one another through an intricately interconnected network of mycorrhizal fungi that colonize trees’ roots. In more recent work, she has found evidence that trees recognize their own kin and favor them with the lion’s share of their bounty, especially when the saplings are most vulnerable.

Simard’s first book, Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest, was released by Knopf this week. In it, she argues that forests are not collections of isolated organisms but webs of constantly evolving relationships. Humans have been unraveling these webs for years, she says, through destructive practices such as clear-cutting and fire suppression. Now they are causing climate change to advance faster than trees can adapt, leading to species die-offs and a sharp increase in infestations by pests such as the bark beetles that have devastated forests throughout western North America.

More here.

Meet the Other Social Influencers of the Animal Kingdom

Natalie Angier in The New York Times:

Julia, her friends and family agreed, had style. When, out of the blue, the 18-year-old chimpanzee began inserting long, stiff blades of grass into one or both ears and then went about her day with her new statement accessories clearly visible to the world, the other chimpanzees at the Chimfunshi wildlife sanctuary in Zambia were dazzled.

Julia, her friends and family agreed, had style. When, out of the blue, the 18-year-old chimpanzee began inserting long, stiff blades of grass into one or both ears and then went about her day with her new statement accessories clearly visible to the world, the other chimpanzees at the Chimfunshi wildlife sanctuary in Zambia were dazzled.

Pretty soon, they were trying it, too: first her son, then her two closest female friends, then a male friend, out to eight of the 10 chimps in the group, all of them struggling, in front of Julia the Influencer — and hidden video cameras — to get the grass-in-the-ear routine just right. “It was quite funny to see,” said Edwin van Leeuwen of the University of Antwerp, who studies animal culture. “They tried again and again without success. They shivered through their whole bodies.”

Dr. van Leeuwen tried it himself and understood why.

“It’s not a pleasant feeling, poking a piece of grass far enough into the ear to stay there,” he said. But once the chimpanzees had mastered the technique, they repeated it often, proudly, almost ritualistically, fiddling with the inserted blades to make sure others were suitably impressed.

Julia died more than two years ago, yet her grassy-ear routine — a tradition that arose spontaneously, spread through social networks and skirts uncomfortably close to a human meme or fad — lives on among her followers in the sanctuary. The behavior is just one of many surprising examples of animal culture that researchers have lately divulged, as a vivid summary makes clear in a recent issue of Science. Culture was once considered the patented property of human beings: We have the art, science, music and online shopping; animals have the instinct, imprinting and hard-wired responses. But that dismissive attitude toward nonhuman minds turns out to be more deeply misguided with every new finding of animal wit or whimsy: Culture, as many biologists now understand it, is much bigger than we are.

More here.

Sunday, May 9, 2021

The Ten Thousand Things

Suneeta Peres da Costa in the Sydney Review of Books:

The bag of drugs is sitting untouched on the kitchen bench beside the cans of diced tomatoes and chickpeas I’d earlier quarantined. They – cans not drugs – may be useful, I think, although in less apocalyptic times, I might prefer to soak dried chickpeas to make hummus or chana masala. The chickpea glut follows a 9pm masked assault of Harris Farm Leichhardt and the fact the ex has recently turned up unannounced with a care package of more canned pulses, organic brown rice and greens than I have room to store. An Amma devotee never known to hug spontaneously, he’d stood at the mandated distance of one Kylie Minogue on the other side of my gate (less gateless gate than gate that never shuts properly, the broken latch, I observed as he handed me the box, one of the ten thousand things now unlikely to be repaired…).

The bag of drugs is sitting untouched on the kitchen bench beside the cans of diced tomatoes and chickpeas I’d earlier quarantined. They – cans not drugs – may be useful, I think, although in less apocalyptic times, I might prefer to soak dried chickpeas to make hummus or chana masala. The chickpea glut follows a 9pm masked assault of Harris Farm Leichhardt and the fact the ex has recently turned up unannounced with a care package of more canned pulses, organic brown rice and greens than I have room to store. An Amma devotee never known to hug spontaneously, he’d stood at the mandated distance of one Kylie Minogue on the other side of my gate (less gateless gate than gate that never shuts properly, the broken latch, I observed as he handed me the box, one of the ten thousand things now unlikely to be repaired…).

I hadn’t the heart to tell him I already had enough chickpeas.

More here.

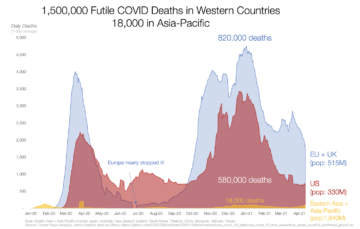

The Pandemic: The true reasons why the West failed

Tomas Pueyo in Uncharted Territories:

Soon, over 1.5 million people will have died of COVID in Western countries.

Soon, over 1.5 million people will have died of COVID in Western countries.

1.5 million futile, needless deaths. 1.5 million wasted lives.

Meanwhile, in a block of Asia-Pacific countries with a population over twice as big, they lost 18,000 people.

By the way, that death count in the West is an understatement. Counting excess deaths, you get 735,000 COVID deaths in the US. That’s more than all combat deaths the US has ever had (~660k) in all wars.

More here.

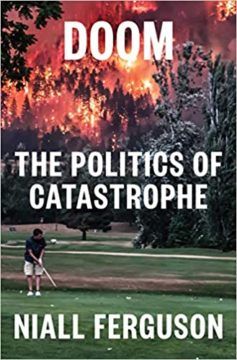

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe—A Review

Jared Marcel Pollen in Quillette:

Niall Ferguson’s new book, Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe, shows us through a tapestry of disasters just how entwined we are with our volatile environment, and serves us a biting and inconvenient thesis: that many disasters, even those dubbed “natural,” are to some extent the result of human error. “It is tempting but misleading,” Ferguson writes, “to divide disasters into natural and man-made … a natural disaster is a disaster in terms of human lives lost only to the extent of its direct or indirect impact on human settlements.” Disasters, in other words, are disasters not simply because they occur, but because of whom they affect, because they strike and destabilize systems.

Niall Ferguson’s new book, Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe, shows us through a tapestry of disasters just how entwined we are with our volatile environment, and serves us a biting and inconvenient thesis: that many disasters, even those dubbed “natural,” are to some extent the result of human error. “It is tempting but misleading,” Ferguson writes, “to divide disasters into natural and man-made … a natural disaster is a disaster in terms of human lives lost only to the extent of its direct or indirect impact on human settlements.” Disasters, in other words, are disasters not simply because they occur, but because of whom they affect, because they strike and destabilize systems.

The zoology of catastrophe is as follows: “Gray Rhinos” (things we can see coming), “Black Swans” (defined by Nassim Taleb as things that “seem to us, on the basis of our limited experience, to be impossible”) and “Dragon Kings” (vast disasters that lie outside normal power law distributions). The history of disasters, Ferguson writes, is the “poorly managed zoo” of these creatures, “as well as a great many unfortunate but inconsequential events and an infinity of nonevents.”

More here.

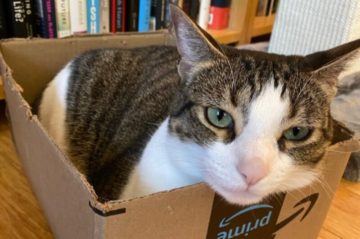

What cats’ love of boxes and squares can tell us about their visual perception

Jennifer Ouellette in Ars Technica:

It is a truth universally acknowledged—at least by those of the feline persuasion—that an empty box on the floor must be in want of a cat. Ditto for laundry baskets, suitcases, sinks, and even cat carriers (when not used as transport to the vet). This behavior is generally attributed to the fact that cats feel safer when squeezed into small spaces, but it might also be able to tell us something about feline visual perception. That’s the rationale behind a new study in the journal Applied Animal Behaviour Science with a colorful title: “If I fits I sits: A citizen science investigation into illusory contour susceptibility in domestic cats (Felis silvers catus).”

It is a truth universally acknowledged—at least by those of the feline persuasion—that an empty box on the floor must be in want of a cat. Ditto for laundry baskets, suitcases, sinks, and even cat carriers (when not used as transport to the vet). This behavior is generally attributed to the fact that cats feel safer when squeezed into small spaces, but it might also be able to tell us something about feline visual perception. That’s the rationale behind a new study in the journal Applied Animal Behaviour Science with a colorful title: “If I fits I sits: A citizen science investigation into illusory contour susceptibility in domestic cats (Felis silvers catus).”

The paper was inspired in part by a 2017 viral Twitter hashtag, #CatSquares, in which users posted pictures of their cats sitting inside squares marked out on the floor with tape—kind of a virtual box. The following year, lead author Gabriella Smith, a graduate student at Hunter College (CUNY) in New York City, attended a lecture by co-author Sarah-Elizabeth Byosiere, who heads the Thinking Dog Center at Hunter. Byosiere studies canine behavior and cognition, and she spoke about dogs’ susceptibility to visual illusions. While playing with her roommate’s cat later that evening, Smith recalled the Twitter hashtag and wondered if she could find a visual illusion that looked like a square to test on cats.

Smith found it in the work of the late Italian psychologist and artist Gaetano Kanizsa, who was interested in illusory (subjective) contours that visually evoke the sense of an edge in the brain even if there isn’t really a line or edge there.

More here.

Nationalism Kills

Rafia Zakaria in The Baffler:

The actual problem for India is huge. According to estimates, only 2.2 percent of the current population has been fully vaccinated. India needs 200 to 230 million vaccines a month to vaccinate its 1.5 billion population. Hardly any are available; the much-touted vaccination drive that would make the vaccine available to everyone over eighteen years old lies in disarray. Adar Poonawalla, the CEO of the Serum Institute, has come under fire for undersupply of vaccines and “profiteering” from Covishield, a version of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine. (India shipped sixty million doses abroad before the spike in cases.) In response, Poonawalla noted that the Indian government had ordered only 2.1 million doses in February, and then 120 million more in March 2021 when the numbers started to creep upward. He had not increased capacity, he said, because there simply were no orders from the Indian government. Despite scaling up, he noted, the shortage would last until at least July.

The actual problem for India is huge. According to estimates, only 2.2 percent of the current population has been fully vaccinated. India needs 200 to 230 million vaccines a month to vaccinate its 1.5 billion population. Hardly any are available; the much-touted vaccination drive that would make the vaccine available to everyone over eighteen years old lies in disarray. Adar Poonawalla, the CEO of the Serum Institute, has come under fire for undersupply of vaccines and “profiteering” from Covishield, a version of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine. (India shipped sixty million doses abroad before the spike in cases.) In response, Poonawalla noted that the Indian government had ordered only 2.1 million doses in February, and then 120 million more in March 2021 when the numbers started to creep upward. He had not increased capacity, he said, because there simply were no orders from the Indian government. Despite scaling up, he noted, the shortage would last until at least July.

The Modi government did not have any plans to vaccinate its population and the only way out of the cycle of endless death wrought by the virus is just that: the vaccine. A million people may die in India because of this and many will not even be counted, cremated in the makeshift parking lot crematoriums that are the only option for many. Trump’s loss has not eliminated the white nationalist and nativist ideology that gives his supporters the sense of self and superiority to which they believe they are entitled. Having engulfed the Republican Party, and unwilling still to believe that Trump lost, they are addicted not to what Trump did as head of the government but rather how he affirmed their sense of white racial superiority.

The massive deaths, the shortages of beds, of oxygen, even of wood to burn the bodies, may still not be the end of Modi. In Trumpian fashion, he gives his supporters, many new entrants to the Indian middle class who dislike being outdone by either Muslims, Christians, or even lower caste Hindus, a sense of primordial Hindu superiority. Even far poorer Hindus can buy into this, as laws like the Citizenship Amendment Act suddenly render their Muslim neighbors non-citizens, leaving their assets up for grabs. Like Trump’s followers, Modi’s Hindu nationalist diehards may be too addicted to the idea of reclaiming Hindu dominance to give him up.

More here.

Anita Lane (1959 – 2021)

Michelangelo Lovelace (1961 – 2021)

Jacques d’Amboise (1934 – 2021)

I can’t wait to get back to normal. How long before I’m bored?

Ann Wroe in More Intelligent Life:

Many years ago, on a road trip in America, I found myself in Arcadia. It was not as expected. The Arcadia I imagined was all rolling green hills and verdant woods in which shepherds played their pipes and cross-dressing lovers lounged about on the grass. Arcadia, Kansas, was nothing like that: it was a tiny dot in a great sea of prairie flatness, under a hard blue sky.

Many years ago, on a road trip in America, I found myself in Arcadia. It was not as expected. The Arcadia I imagined was all rolling green hills and verdant woods in which shepherds played their pipes and cross-dressing lovers lounged about on the grass. Arcadia, Kansas, was nothing like that: it was a tiny dot in a great sea of prairie flatness, under a hard blue sky.

This Arcadia had two red-brick storefronts, long abandoned, which were covered with ivy and leaning into the street; a few living stores, including a café with tired net curtains; and a shopfront with the words “City Hall” painted above the windows. Outside it, two middle-aged women were struggling to get the Stars and Stripes to half-mast on a tricky new flagpole, advised or obstructed by two plump young men in a pick-up truck that was parked in the middle of the street. Maybe I was the only other car that passed through Arcadia that day.

America’s pioneers, heading relentlessly west in their lumbering wagons, were easily excited. I also visited Eureka, Kansas, and apparently went through Climax too, though I never noticed. Any place that was halfway comfortable or sheltered, with grazing and water, was immediately hailed as the promised land. This was it: somewhere they could at last stop, settle and get on with the rest of their lives. Just like that place called Normal, for which we now all supposedly sigh. You can go direct to Normal, if you like. You will find that most of the five Normals in America are tiny unincorporated places given their name not for their deep ordinariness, but because they once had a teacher-training college, or “normal school”.

More here.

Saturday, May 8, 2021

Race, Policing, and The Limits of Social Science

Lily Hu in Boston Review:

Lily Hu in Boston Review:

Since the 1970s, the development of causal inference methodology and the rise of large-scale data collection efforts have generated a vast quantitative literature on the effects of race in society. But for all its ever-growing technical sophistication, scholars have yet to come to consensus on basic matters regarding the proper conceptualization and measurement of these effects. What exactly does it mean for race to act as a cause? When do inferences about race make the leap from mere correlation to causation? Where do we draw the line between assumptions about the social world that are needed to get the statistical machinery up and running and assumptions that massively distort how the social world in fact is and works? And what is it that makes quantitative analysis a reliable resource for law and policy making?

In both academic and policy discourse, these questions tend to be crowded out by increasingly esoteric technical work. But they raise deep concerns that no amount of sophisticated statistical practice can resolve, and that will indeed only grow more significant as “evidence-based” debates about race and policing reach new levels of controversy in the United States. We need a more refined appreciation of what social science can offer as a well of inquiry, evidence, and knowledge, and what it can’t. In the tides of latest findings, what we should believe—and what we should give up believing—can never be decided simply by brute appeals to data, cordoned off from judgments of reliability and significance. A commitment to getting the social world right does not require deference to results simply because the approved statistical machinery has been cranked. Indeed in some cases, it may even require that we reject findings, no matter the prestige or sophistication of the social scientific apparatus on which they are built.

More here.

How Radical Is President Biden?

Colonialism applied to Europe

Branko Milanovic over at his Substack:

Branko Milanovic over at his Substack:

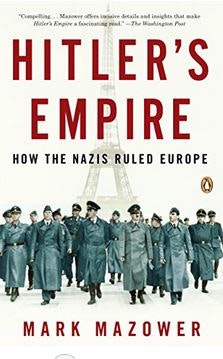

Mark Mazower’s “Hitler’s Empire: How the Nazis ruled Europe” is a magisterial book.

I read it on vacation, and it is not a book I would suggest you take with you to the beach. Unless you want to spoil your vacation. But once you have made such a choice, you cannot stop reading it and the book will stay with you throughout your stay (and I believe much longer).

This Summer I read, almost back-to-back Adam Tooze’s “The deluge” and Mazower’s book. The first covers the period 1916-31, the second, the Nazi rule of Europe 1936-45. They can be practically read as a continuum, but they are two very different books. Tooze’s is, despite all the carnage of World War I and Russian Civil War, an optimistic book in which sincere or feigned idealism is battling conservatism and militarism. As I wrote in my review of Tooze’s book, the emphasis on the failed promise of liberal democracy (but a promise still it was) is a thread that runs through most of the book. Mazower’s book, on the other hand, is unfailingly grim and this is not only because the topic he writes about is much more sinister. The tone is bleaker. It is a book about the unremitting evil. It is the steady accumulation of murders, betrayals, massacres, retaliations, burned villages, conquests, and annihilation that makes for a despairing and yet compelling read. Europe was indeed, as another of Mazower’s book is titled, the dark continent.

Here I would like to discuss another aspect of Mazower’s book that is implicit throughout but is mentioned rather discreetly only in the concluding chapter. It concerns the place of the Second World War in global history. The conventional opinion is that the Second War should be regarded as a continuation of the First. While the First was produced by competing imperialisms, the Second was the outcome of the very imperfect settlement imposed at the end of the War, and the difference in interpretations as to how the War really ended (was it an armistice, or was it an unconditional surrender).

But that interpretation is (perhaps) faulty because it cannot account for the most distinctive character of the World War II, namely that it was the war of extermination in the East (including the Shoah). That is where Mazower’s placing of the War in a much longer European imperial context makes sense.

More here.