Jill Lepore in The New Yorker:

Burnout is generally said to date to 1973; at least, that’s around when it got its name. By the nineteen-eighties, everyone was burned out. In 1990, when the Princeton scholar Robert Fagles published a new English translation of the Iliad, he had Achilles tell Agamemnon that he doesn’t want people to think he’s “a worthless, burnt-out coward.” This expression, needless to say, was not in Homer’s original Greek. Still, the notion that people who fought in the Trojan War, in the twelfth or thirteenth century B.C., suffered from burnout is a good indication of the disorder’s claim to universality: people who write about burnout tend to argue that it exists everywhere and has existed forever, even if, somehow, it’s always getting worse. One Swiss psychotherapist, in a history of burnout published in 2013 that begins with the usual invocation of immediate emergency—“Burnout is increasingly serious and of widespread concern”—insists that he found it in the Old Testament. Moses was burned out, in Numbers 11:14, when he complained to God, “I am not able to bear all this people alone, because it is too heavy for me.” And so was Elijah, in 1 Kings 19, when he “went a day’s journey into the wilderness, and came and sat down under a juniper tree: and he requested for himself that he might die; and said, It is enough.”

Burnout is generally said to date to 1973; at least, that’s around when it got its name. By the nineteen-eighties, everyone was burned out. In 1990, when the Princeton scholar Robert Fagles published a new English translation of the Iliad, he had Achilles tell Agamemnon that he doesn’t want people to think he’s “a worthless, burnt-out coward.” This expression, needless to say, was not in Homer’s original Greek. Still, the notion that people who fought in the Trojan War, in the twelfth or thirteenth century B.C., suffered from burnout is a good indication of the disorder’s claim to universality: people who write about burnout tend to argue that it exists everywhere and has existed forever, even if, somehow, it’s always getting worse. One Swiss psychotherapist, in a history of burnout published in 2013 that begins with the usual invocation of immediate emergency—“Burnout is increasingly serious and of widespread concern”—insists that he found it in the Old Testament. Moses was burned out, in Numbers 11:14, when he complained to God, “I am not able to bear all this people alone, because it is too heavy for me.” And so was Elijah, in 1 Kings 19, when he “went a day’s journey into the wilderness, and came and sat down under a juniper tree: and he requested for himself that he might die; and said, It is enough.”

To be burned out is to be used up, like a battery so depleted that it can’t be recharged. In people, unlike batteries, it is said to produce the defining symptoms of “burnout syndrome”: exhaustion, cynicism, and loss of efficacy. Around the world, three out of five workers say they’re burned out. A 2020 U.S. study put that figure at three in four. A recent book claims that burnout afflicts an entire generation. In “Can’t Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation,” the former BuzzFeed News reporter Anne Helen Petersen figures herself as a “pile of embers.” The earth itself suffers from burnout.

More here.

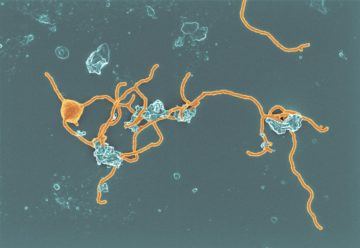

Evolutionary biologist David Baum was thrilled to flick through a preprint in August 2019 and come face-to-face — well, face-to-cell — with a distant cousin. Baum, who works at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, was looking at an archaeon: a type of microorganism best known for living in extreme environments, such as deep-ocean vents and acid lakes. Archaea can look similar to bacteria, but have about as much in common with them as they do with a banana. The one in the bioRxiv preprint had tentacle-like projections, making the cells look like meatballs with some strands of spaghetti attached. Baum had spent a lot of time imagining what humans’ far-flung ancestors might look like, and this microbe was a perfect doppelgänger.

Evolutionary biologist David Baum was thrilled to flick through a preprint in August 2019 and come face-to-face — well, face-to-cell — with a distant cousin. Baum, who works at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, was looking at an archaeon: a type of microorganism best known for living in extreme environments, such as deep-ocean vents and acid lakes. Archaea can look similar to bacteria, but have about as much in common with them as they do with a banana. The one in the bioRxiv preprint had tentacle-like projections, making the cells look like meatballs with some strands of spaghetti attached. Baum had spent a lot of time imagining what humans’ far-flung ancestors might look like, and this microbe was a perfect doppelgänger. “Ethnoscience” and “Indigenous science”, along with more fine-grained designations like “ethnomathematics”, “ethnoastronomy”, etc., are common terms used to describe both Indigenous systems of knowledge, as well as the scholarly study of these systems. These terms are contested among specialists, for reasons I will not address here. More recently they have also been swallowed up by the voracious beast that is our neverending culture war, and are now hotly contested by people who know nothing about them as well.

“Ethnoscience” and “Indigenous science”, along with more fine-grained designations like “ethnomathematics”, “ethnoastronomy”, etc., are common terms used to describe both Indigenous systems of knowledge, as well as the scholarly study of these systems. These terms are contested among specialists, for reasons I will not address here. More recently they have also been swallowed up by the voracious beast that is our neverending culture war, and are now hotly contested by people who know nothing about them as well. For as much as people talk about food, a good case can be made that we don’t give it the attention or respect it actually deserves. Food is central to human life, and how we go about the process of creating and consuming it — from agriculture to distribution to cooking to dining — touches the most mundane aspects of our daily routines as well as large-scale questions of geopolitics and culture. Rachel Laudan is a historian of science whose masterful book,

For as much as people talk about food, a good case can be made that we don’t give it the attention or respect it actually deserves. Food is central to human life, and how we go about the process of creating and consuming it — from agriculture to distribution to cooking to dining — touches the most mundane aspects of our daily routines as well as large-scale questions of geopolitics and culture. Rachel Laudan is a historian of science whose masterful book,  Could you define what you mean by “noise” in the book, in layman’s terms – how does it differ from things like subjectivity or error?

Could you define what you mean by “noise” in the book, in layman’s terms – how does it differ from things like subjectivity or error? P

P For centuries, humans have been captivated by the beauty of the betta. Their slender bodies and oversized fins, which hang like bolts of silk, come in a variety of vibrant colors seldom seen in nature. However, bettas, also known as the Siamese fighting fish, did not become living works of art on their own. The betta’s elaborate colors and long, flowing fins are the product of a millennium of careful selective breeding. Or as Yi-Kai Tea, a doctoral candidate at the University of Sydney who studies the evolution and speciation of fishes, put it, “quite literally the fish equivalent of dog domestication.”

For centuries, humans have been captivated by the beauty of the betta. Their slender bodies and oversized fins, which hang like bolts of silk, come in a variety of vibrant colors seldom seen in nature. However, bettas, also known as the Siamese fighting fish, did not become living works of art on their own. The betta’s elaborate colors and long, flowing fins are the product of a millennium of careful selective breeding. Or as Yi-Kai Tea, a doctoral candidate at the University of Sydney who studies the evolution and speciation of fishes, put it, “quite literally the fish equivalent of dog domestication.” Along a dried-up channel of the Euphrates river in modern-day Iraq, broken mud bricks poke out of vast, dusty ruins. They are the remains of Uruk, the birthplace of writing that’s better known in popular culture today as the city once ruled by the legendary king Gilgamesh, the hero of an epic about his struggle with life, love and death. Sometimes called the oldest story in the world, the Epic of Gilgamesh continues to resonate with modern audiences more than

Along a dried-up channel of the Euphrates river in modern-day Iraq, broken mud bricks poke out of vast, dusty ruins. They are the remains of Uruk, the birthplace of writing that’s better known in popular culture today as the city once ruled by the legendary king Gilgamesh, the hero of an epic about his struggle with life, love and death. Sometimes called the oldest story in the world, the Epic of Gilgamesh continues to resonate with modern audiences more than  It wasn’t long into the pandemic before Simon Carley realized we had an evidence problem. It was early 2020, and COVID-19 infections were starting to lap at the shores of the United Kingdom, where Carley is an emergency-medicine doctor at hospitals in Manchester. Carley is also a specialist in evidence-based medicine — the transformative idea that physicians should decide how to treat people by referring to rigorous evidence, such as clinical trials.

It wasn’t long into the pandemic before Simon Carley realized we had an evidence problem. It was early 2020, and COVID-19 infections were starting to lap at the shores of the United Kingdom, where Carley is an emergency-medicine doctor at hospitals in Manchester. Carley is also a specialist in evidence-based medicine — the transformative idea that physicians should decide how to treat people by referring to rigorous evidence, such as clinical trials. Joe Biden’s American Families Plan is something of a miracle. It carries out goals that advocates have only dreamed of.

Joe Biden’s American Families Plan is something of a miracle. It carries out goals that advocates have only dreamed of.  When I read Chaos Monkeys the first time I was annoyed, because this was Antonio’s third career at least — he’d also worked at Goldman, Sachs — and he tossed off a memorable bestseller like it was nothing. Nearly all autobiographies fail because the genre requires total honesty, and not only do few writers have the stomach for turning the razor on themselves, most still have one eye on future job offers or circles of friends, and so keep the bulk of their interesting thoughts sidelined — you’re usually reading a résumé, not a book.

When I read Chaos Monkeys the first time I was annoyed, because this was Antonio’s third career at least — he’d also worked at Goldman, Sachs — and he tossed off a memorable bestseller like it was nothing. Nearly all autobiographies fail because the genre requires total honesty, and not only do few writers have the stomach for turning the razor on themselves, most still have one eye on future job offers or circles of friends, and so keep the bulk of their interesting thoughts sidelined — you’re usually reading a résumé, not a book. unch:

unch: Archaeologists and other scientists are beginning to unravel the story of our most intimate technology: clothing. They’re learning when and why our ancestors first started to wear clothes, and how their adoption was crucial to the evolutionary success of our ancestors when they faced climate change on a massive scale during the Pleistocene ice ages. These investigations have revealed a new twist to the story, assigning a much more prominent role to clothing than previously imagined. After the last ice age, global warming prompted people in many areas to change their clothes, from animal hides to textiles. This change in clothing material, I suspect, could be what triggered one of the greatest changes in the life of humanity. Not food but clothing led to the agricultural revolution.

Archaeologists and other scientists are beginning to unravel the story of our most intimate technology: clothing. They’re learning when and why our ancestors first started to wear clothes, and how their adoption was crucial to the evolutionary success of our ancestors when they faced climate change on a massive scale during the Pleistocene ice ages. These investigations have revealed a new twist to the story, assigning a much more prominent role to clothing than previously imagined. After the last ice age, global warming prompted people in many areas to change their clothes, from animal hides to textiles. This change in clothing material, I suspect, could be what triggered one of the greatest changes in the life of humanity. Not food but clothing led to the agricultural revolution.

Thomas Meaney in The New Yorker:

Thomas Meaney in The New Yorker: