Selection

I have seen a deer with antlers tipped in gold,

and it was the most beautiful thing that I can imagine.

By daylight the antler’s branches burned like tallow candles

burning in darkness. In darkness they burned like branching stars.

It could be that somewhere near there’s a river of running gold,

where the deer, stooping its head to drink, was gilt by chance.

But I have been looking for that river all my life,

and though the sun throws coins, they sink out of sight in the water.

You might think this was a dream, but no: here is the dream.

The deer stood constellated above me as I slept,

and said, with its golden tongue, I grow the gold from inside,

according to the laws of natural selection.

The gold draws hunters to me, drawn to me above all,

and meek as I am, I am the first and most readily martyred.

The rewards due to the martyr are greater than you can imagine,

and so I thrive, and so I am selected for.

I would have thought endurance in this world, I said,

is what selection means, and whatever comes afterward

cannot flow backward to favor any living things.

That shows what you know, said the deer, and I awoke.

by Jeff Dolven

from The Yale Review

Social media have gutted institutions: journalism, education, and increasingly the halls of government too. When Marjorie Taylor Greene displays some dumb-as-hell anti-communist Scooby-Doo meme before congress, blown up on poster-board and held by some hapless staffer, and declares “This meme is very real”, she is channeling words far, far wiser than the mind that produced them. We’re all just sharing memes now, and those of us who hope to succeed out there in “reality”, in congress and classrooms and so on, momentarily removed from our screens and feeds, must learn how to keep the memes going even then. “Real-world” events, in other words, are staged by the victors in our society principally with an eye to the potential virality of their online uptake. And when virality is the desired outcome, clicks effected in support or in disgust are all the same. Thus the naive idea that AOC wore her “Tax the Rich” gown to a particular event attended by a select crowd within a well-defined physical space completely distorts the motivation behind the gesture, which was, obviously, to make waves not during, but immediately after, the event, not for the people at the event, but for all the people who were not invited.

Social media have gutted institutions: journalism, education, and increasingly the halls of government too. When Marjorie Taylor Greene displays some dumb-as-hell anti-communist Scooby-Doo meme before congress, blown up on poster-board and held by some hapless staffer, and declares “This meme is very real”, she is channeling words far, far wiser than the mind that produced them. We’re all just sharing memes now, and those of us who hope to succeed out there in “reality”, in congress and classrooms and so on, momentarily removed from our screens and feeds, must learn how to keep the memes going even then. “Real-world” events, in other words, are staged by the victors in our society principally with an eye to the potential virality of their online uptake. And when virality is the desired outcome, clicks effected in support or in disgust are all the same. Thus the naive idea that AOC wore her “Tax the Rich” gown to a particular event attended by a select crowd within a well-defined physical space completely distorts the motivation behind the gesture, which was, obviously, to make waves not during, but immediately after, the event, not for the people at the event, but for all the people who were not invited. Topologists study the properties of general versions of shapes, called manifolds. Their animating goal is to classify them. In that effort, there are a few key distinctions. What exactly are manifolds, and what notion of sameness do we have in mind when we compare them?

Topologists study the properties of general versions of shapes, called manifolds. Their animating goal is to classify them. In that effort, there are a few key distinctions. What exactly are manifolds, and what notion of sameness do we have in mind when we compare them? There is great emotional weight in literature. Anyone who has cried for the death of Old Yeller, laughed at the antics of Lucky Jim, or been thrilled by the adventures of Simon Templar can attest to that simple fact. What has never been simple is understanding why a string of written words can create such an emotional response, or possibly more important, why some strings achieve it so much more effectively than others.

There is great emotional weight in literature. Anyone who has cried for the death of Old Yeller, laughed at the antics of Lucky Jim, or been thrilled by the adventures of Simon Templar can attest to that simple fact. What has never been simple is understanding why a string of written words can create such an emotional response, or possibly more important, why some strings achieve it so much more effectively than others. I’m an audiovisual translator, which means that I—and others like me—help you understand the languages spoken on screen: You just click that little speech bubble icon in the bottom-right corner of your preferred streaming service, select the subtitles or the dub, and away you go. These scripts are all written by someone like myself, sitting quietly at a computer and spending day after day trying to figure out, “What are they actually saying here?”

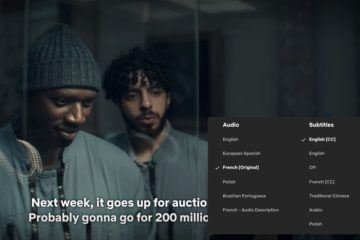

I’m an audiovisual translator, which means that I—and others like me—help you understand the languages spoken on screen: You just click that little speech bubble icon in the bottom-right corner of your preferred streaming service, select the subtitles or the dub, and away you go. These scripts are all written by someone like myself, sitting quietly at a computer and spending day after day trying to figure out, “What are they actually saying here?” H

H On the cover of her new album, Dar Williams stands on a floating platform in a lake. A breeze ripples the water so that it’s as wrinkled as elephant skin. As Ms. Williams gazes toward an unseen horizon, her scarlet shawl flutters behind her like a vapor trail. The atomistic image is metaphorical. Ms. Williams says the photo, taken by a drone, makes her look like a red dot destination marker on a map. The album, debuting Oct. 1, is titled “I’ll Meet You Here.” “Somehow we have to figure out how to continue to meet the moment and meet one another,” even when we seem to be stranded, explains the folk singer in a phone call.

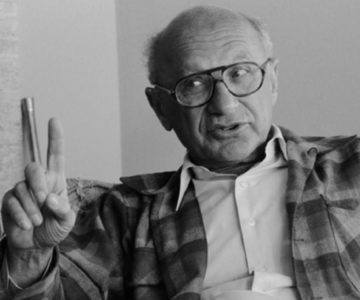

On the cover of her new album, Dar Williams stands on a floating platform in a lake. A breeze ripples the water so that it’s as wrinkled as elephant skin. As Ms. Williams gazes toward an unseen horizon, her scarlet shawl flutters behind her like a vapor trail. The atomistic image is metaphorical. Ms. Williams says the photo, taken by a drone, makes her look like a red dot destination marker on a map. The album, debuting Oct. 1, is titled “I’ll Meet You Here.” “Somehow we have to figure out how to continue to meet the moment and meet one another,” even when we seem to be stranded, explains the folk singer in a phone call. Nancy MacLean over at INET:

Nancy MacLean over at INET: James Meadway in New Statesman:

James Meadway in New Statesman:

T

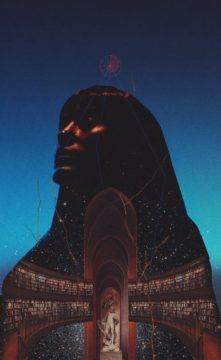

T “Cloud Cuckoo Land,” a follow-up to Doerr’s best-selling novel “All the Light We Cannot See,” is, among other things, a paean to the nameless people who have played a role in the transmission of ancient texts and preserved the tales they tell. But it’s also about the consolations of stories and the balm they have provided for millenniums. It’s a wildly inventive novel that teems with life, straddles an enormous range of experience and learning, and embodies the storytelling gifts that it celebrates. It also pulls off a resolution that feels both surprising and inevitable, and that compels you back to the opening of the book with a head-shake of admiration at the Swiss-watchery of its construction.

“Cloud Cuckoo Land,” a follow-up to Doerr’s best-selling novel “All the Light We Cannot See,” is, among other things, a paean to the nameless people who have played a role in the transmission of ancient texts and preserved the tales they tell. But it’s also about the consolations of stories and the balm they have provided for millenniums. It’s a wildly inventive novel that teems with life, straddles an enormous range of experience and learning, and embodies the storytelling gifts that it celebrates. It also pulls off a resolution that feels both surprising and inevitable, and that compels you back to the opening of the book with a head-shake of admiration at the Swiss-watchery of its construction. “Let me start big. The mission of the Claremont Institute is to save Western civilization,” says Ryan Williams, the organization’s president, looking at the camera, in a crisp navy suit. “We’ve always aimed high.” A trumpet blares. America’s founding documents flash across the screen. Welcome to the intellectual home of America’s Trumpist right.

“Let me start big. The mission of the Claremont Institute is to save Western civilization,” says Ryan Williams, the organization’s president, looking at the camera, in a crisp navy suit. “We’ve always aimed high.” A trumpet blares. America’s founding documents flash across the screen. Welcome to the intellectual home of America’s Trumpist right. Even Noah Webster, that master of words, did not have a name for the terrible sickness. “In May 1735,” he wrote in A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases, “in a wet cold season, appeared at Kingston, an inland town in New-Hampshire, situated in a low plain, a disease among children, commonly called the ‘throat distemper,’ of a most malignant kind, and by far the most fatal ever known in this country.” Webster noted the symptoms, including general weakness and a swollen neck. The disease moved through the colonies, he wrote, “and gradually travelled southward, almost stripping the country of children….It was literally the plague among children. Many families lost three and four children—many lost all.” And children who survived generally went on to die young, he wrote from his vantage point of more than half a century later. The “throat distemper” had somehow weakened their bodies.

Even Noah Webster, that master of words, did not have a name for the terrible sickness. “In May 1735,” he wrote in A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases, “in a wet cold season, appeared at Kingston, an inland town in New-Hampshire, situated in a low plain, a disease among children, commonly called the ‘throat distemper,’ of a most malignant kind, and by far the most fatal ever known in this country.” Webster noted the symptoms, including general weakness and a swollen neck. The disease moved through the colonies, he wrote, “and gradually travelled southward, almost stripping the country of children….It was literally the plague among children. Many families lost three and four children—many lost all.” And children who survived generally went on to die young, he wrote from his vantage point of more than half a century later. The “throat distemper” had somehow weakened their bodies.