Alex Dean in Prospect:

What do we think we know about Baruch Spinoza? We know he was one of the greatest philosophers of the Enlightenment: the Dutch thinker was a champion of free intellectual inquiry who broke new ground in metaphysics, epistemology and philosophy of mind. His magnum opus, the Ethics, put forward a system of breathtaking originality that is still celebrated today. We might know that he was a pioneer of the rationalist school that emerged in the 17th century. But more than any of this, most of us know something about his philosophy of religion: Spinoza’s writing is famously atheistic.

What do we think we know about Baruch Spinoza? We know he was one of the greatest philosophers of the Enlightenment: the Dutch thinker was a champion of free intellectual inquiry who broke new ground in metaphysics, epistemology and philosophy of mind. His magnum opus, the Ethics, put forward a system of breathtaking originality that is still celebrated today. We might know that he was a pioneer of the rationalist school that emerged in the 17th century. But more than any of this, most of us know something about his philosophy of religion: Spinoza’s writing is famously atheistic.

In his own day, Spinoza was branded a heretic and accused of trivialising God’s role in the universe and human affairs. Cast out of the Dutch Jewish community at the age of 23 for spouting “horrible heresies,” he opted for permanent outsider status by refusing to convert to Christianity. He disputed the existence of miracles and the afterlife and challenged the authority of the Bible. His Theologico-Political Treatise was condemned as “a book forged in hell… by the devil himself.” The Ethics was placed on the Catholic Church’s index of forbidden books.

More here.

Einstein recalled how, at the age of 16, he imagined chasing after a beam of light and that the thought experiment had played a memorable role in his development of special relativity. Famous as it is, it has proven difficult to understand just how the thought experiment delivers its results. It fails to generate serious problems for an ether based electrodynamics.

Einstein recalled how, at the age of 16, he imagined chasing after a beam of light and that the thought experiment had played a memorable role in his development of special relativity. Famous as it is, it has proven difficult to understand just how the thought experiment delivers its results. It fails to generate serious problems for an ether based electrodynamics.  The

The  Folk horror plays on myths as lure and nightmare, but The Green Knight is more focused on the radical otherness of the natural world. Lowery’s “horror-ized” version of Gawain’s quest, with its defamiliarizing photography of Ireland’s forests, bogs, and caves, creates a landscape that feels far from “natural.” It contains uncanny specters, eerie giants, haunted woods, talking foxes, and, of course, the story’s titular tree-like green weirdo who picks up his own head off the floor after Gawain severs it. Nature has grown tired of having axes driven into its neck and is now fighting back, threatening to destabilize the human world. These details feel redolent of what English horror writer Gary Budden calls “

Folk horror plays on myths as lure and nightmare, but The Green Knight is more focused on the radical otherness of the natural world. Lowery’s “horror-ized” version of Gawain’s quest, with its defamiliarizing photography of Ireland’s forests, bogs, and caves, creates a landscape that feels far from “natural.” It contains uncanny specters, eerie giants, haunted woods, talking foxes, and, of course, the story’s titular tree-like green weirdo who picks up his own head off the floor after Gawain severs it. Nature has grown tired of having axes driven into its neck and is now fighting back, threatening to destabilize the human world. These details feel redolent of what English horror writer Gary Budden calls “ For a film about dying, the sick bodies hold their illnesses discreetly. There are no waning limbs, no unsightly fluids, no Kaposi sarcoma lesions. Perhaps this is a line of spectacle Bordowitz will not cross. The subjects seem healthy, for now. But there is a rupture in the final moments of the film, after the credits have rolled. It’s an outtake from the opening scene. “Death is the death of consciousness,” says Bordowitz, reclining in bed, pants-less. “I hope there’s nothing after this,” and then he breaks character and starts laughing, as does whoever is filming. But the laughter turns to coughing, Bordowitz can’t catch his breath. Is it the smoking? There’s an ashtray balanced on his

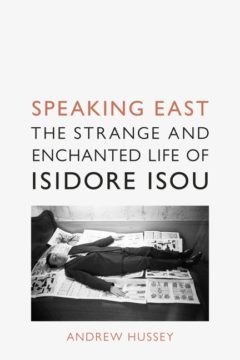

For a film about dying, the sick bodies hold their illnesses discreetly. There are no waning limbs, no unsightly fluids, no Kaposi sarcoma lesions. Perhaps this is a line of spectacle Bordowitz will not cross. The subjects seem healthy, for now. But there is a rupture in the final moments of the film, after the credits have rolled. It’s an outtake from the opening scene. “Death is the death of consciousness,” says Bordowitz, reclining in bed, pants-less. “I hope there’s nothing after this,” and then he breaks character and starts laughing, as does whoever is filming. But the laughter turns to coughing, Bordowitz can’t catch his breath. Is it the smoking? There’s an ashtray balanced on his  Nevertheless, when the Dadaist poet Tristan Tzara was buried at Montparnasse in the winter of 1963, Isou and his followers arrived uninvited at the cemetery and fought with the communists who had also come to pay their respects. As Isou began to make a speech, he was informed that Tzara’s family had wished for the funeral to pass in silence. Undeterred, he began to declaim a lettriste poem: ‘étli, tzara, jofué lochigran télebile sarkénidan.’

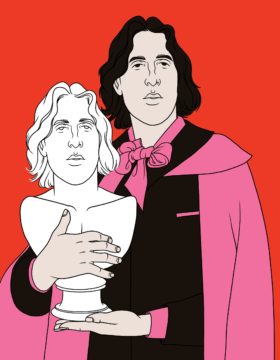

Nevertheless, when the Dadaist poet Tristan Tzara was buried at Montparnasse in the winter of 1963, Isou and his followers arrived uninvited at the cemetery and fought with the communists who had also come to pay their respects. As Isou began to make a speech, he was informed that Tzara’s family had wished for the funeral to pass in silence. Undeterred, he began to declaim a lettriste poem: ‘étli, tzara, jofué lochigran télebile sarkénidan.’ Oscar Wilde was in the dock when he observed himself becoming two people. It was a Saturday in May, 1895, the final day of his trial for “gross indecency,” and the solicitor general, Frank Lockwood, was in the midst of a closing address for the prosecution. His catalogue of accusations, shot through with moral disgust, struck Wilde as an “appalling denunciation”—“like a thing out of Tacitus, like a passage in Dante,” as he wrote two years later. He was “sickened with horror” at what he heard. But the sensation was short-lived: “Suddenly it occurred to me, How splendid it would be, if I was saying all this about myself. I saw then at once that what is said of a man is nothing. The point is, who says it.” At the critical moment, he was able to transform the drama in his imagination by taking both roles, substituting the real Lockwood with an alternative Wilde, one who could control the courtroom and its narrative.

Oscar Wilde was in the dock when he observed himself becoming two people. It was a Saturday in May, 1895, the final day of his trial for “gross indecency,” and the solicitor general, Frank Lockwood, was in the midst of a closing address for the prosecution. His catalogue of accusations, shot through with moral disgust, struck Wilde as an “appalling denunciation”—“like a thing out of Tacitus, like a passage in Dante,” as he wrote two years later. He was “sickened with horror” at what he heard. But the sensation was short-lived: “Suddenly it occurred to me, How splendid it would be, if I was saying all this about myself. I saw then at once that what is said of a man is nothing. The point is, who says it.” At the critical moment, he was able to transform the drama in his imagination by taking both roles, substituting the real Lockwood with an alternative Wilde, one who could control the courtroom and its narrative.

The control of infectious disease is one of the unambiguously great accomplishments of our species. Through a succession of overlapping and mutually reinforcing innovations at several scales—from public health reforms and the so-called hygiene revolution, to chemical controls and biomedical interventions like antibiotics, vaccines, and improvements to patient care—humans have learned to make the environments we inhabit unfit for microbes that cause us harm. This transformation has prevented immeasurable bodily pain and allowed billions of humans the chance to reach their full potential. It has relieved countless parents from the anguish of burying their children. It has remade our basic assumptions about life and death. Scholars have found plenty of candidates for what made us “modern” (railroads, telephones, science, Shakespeare), but the control of our microbial adversaries is as compelling as any of them. The mastery of microbes is so elemental and so intimately bound up with the other features of modernity—economic growth, mass education, the empowerment of women—that it is hard to imagine a counterfactual path to the modern world in which we lack a basic level of control over our germs. Modernity and pestilence are mutually exclusive; the COVID-19 pandemic only underscores their incompatibility.

The control of infectious disease is one of the unambiguously great accomplishments of our species. Through a succession of overlapping and mutually reinforcing innovations at several scales—from public health reforms and the so-called hygiene revolution, to chemical controls and biomedical interventions like antibiotics, vaccines, and improvements to patient care—humans have learned to make the environments we inhabit unfit for microbes that cause us harm. This transformation has prevented immeasurable bodily pain and allowed billions of humans the chance to reach their full potential. It has relieved countless parents from the anguish of burying their children. It has remade our basic assumptions about life and death. Scholars have found plenty of candidates for what made us “modern” (railroads, telephones, science, Shakespeare), but the control of our microbial adversaries is as compelling as any of them. The mastery of microbes is so elemental and so intimately bound up with the other features of modernity—economic growth, mass education, the empowerment of women—that it is hard to imagine a counterfactual path to the modern world in which we lack a basic level of control over our germs. Modernity and pestilence are mutually exclusive; the COVID-19 pandemic only underscores their incompatibility. Traditional physics works within the “Laplacian paradigm”: you give me the state of the universe (or some closed system), some equations of motion, then I use those equations to evolve the system through time.

Traditional physics works within the “Laplacian paradigm”: you give me the state of the universe (or some closed system), some equations of motion, then I use those equations to evolve the system through time.  I gave my first lecture, at my first academic job, behind a wall of plexiglass, speaking to an awkwardly spaced out group of masked students who had maybe already given up – and honestly, who could blame them? I walked in sweating and late because my building’s social distancing protocol required me to run up five floors and down two to get to my third floor classroom. Leaning into the mic, I opened with the joke: “Welcome to apocalyptic poetry!”

I gave my first lecture, at my first academic job, behind a wall of plexiglass, speaking to an awkwardly spaced out group of masked students who had maybe already given up – and honestly, who could blame them? I walked in sweating and late because my building’s social distancing protocol required me to run up five floors and down two to get to my third floor classroom. Leaning into the mic, I opened with the joke: “Welcome to apocalyptic poetry!” It’s 2036, and you have kidney failure. Until recently, this condition meant months or years of gruelling dialysis, while you hoped that a suitable donor would emerge to provide you with replacement kidneys. Today, thanks to a new technology, you’re going to grow your own. A technician collects a small sample of your blood or skin and takes it to a laboratory. There, the cells it contains are separated out, cultured and treated with various drugs. The procedure transforms the cells into induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which, like the cells of an early embryo, are capable of generating any of the body’s tissues. Next, the technician selects a pig embryo that has been engineered to lack a gene required to grow kidneys, and injects your iPS cells into it. This embryo is implanted in a surrogate sow, where it develops into a young pig that has two kidneys consisting of your human cells. Eventually, these kidneys are transplanted into your body, massively extending your life expectancy.

It’s 2036, and you have kidney failure. Until recently, this condition meant months or years of gruelling dialysis, while you hoped that a suitable donor would emerge to provide you with replacement kidneys. Today, thanks to a new technology, you’re going to grow your own. A technician collects a small sample of your blood or skin and takes it to a laboratory. There, the cells it contains are separated out, cultured and treated with various drugs. The procedure transforms the cells into induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which, like the cells of an early embryo, are capable of generating any of the body’s tissues. Next, the technician selects a pig embryo that has been engineered to lack a gene required to grow kidneys, and injects your iPS cells into it. This embryo is implanted in a surrogate sow, where it develops into a young pig that has two kidneys consisting of your human cells. Eventually, these kidneys are transplanted into your body, massively extending your life expectancy. The curse of genre is that it encourages filmmakers to downplay causes in the interest of effects. In the best genre movies, the quantity and power of these effects serve as sufficient compensation for the thinned-out drama. “Titane,” the new film by Julia Ducournau, is a genre film, a twist on horror with a twist on family—like Ducournau’s first feature, “Raw.” But “Titane” is far stronger, far wilder, far stranger. The radical fantasy of its premise—a woman gets impregnated by a car—wrenches the ensuing family drama out of the realm of the ordinary and into one of speculative fantasy and imaginative wonder that demands a suspension of disbelief—which becomes the movie’s very subject.

The curse of genre is that it encourages filmmakers to downplay causes in the interest of effects. In the best genre movies, the quantity and power of these effects serve as sufficient compensation for the thinned-out drama. “Titane,” the new film by Julia Ducournau, is a genre film, a twist on horror with a twist on family—like Ducournau’s first feature, “Raw.” But “Titane” is far stronger, far wilder, far stranger. The radical fantasy of its premise—a woman gets impregnated by a car—wrenches the ensuing family drama out of the realm of the ordinary and into one of speculative fantasy and imaginative wonder that demands a suspension of disbelief—which becomes the movie’s very subject.