David Robson at the BBC:

It is more than 150 years since scientists proved that invisible germs could cause contagious illnesses such as cholera, typhoid, and tuberculosis. The role of microbes in these diseases was soon widely accepted, but “Germ Theory” has continued to surprise ever since – with huge implications for many apparently unrelated areas of medicine.

It is more than 150 years since scientists proved that invisible germs could cause contagious illnesses such as cholera, typhoid, and tuberculosis. The role of microbes in these diseases was soon widely accepted, but “Germ Theory” has continued to surprise ever since – with huge implications for many apparently unrelated areas of medicine.

It was only in the 1980s, after all, that two Australian scientists found that Helicobacter Pylori triggers stomach ulcers. Before that, doctors had blamed the condition on stress, cigarettes and booze. Contemporary scientists considered the idea to be “preposterous”, yet it eventually earned the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2005.

The discovery that the human papillomavirus can cause cervical cancer proved to be similarly controversial, but vaccines against the infection are now saving thousands of lives. Scientists today estimate that around 12% of all human cancers are caused by viruses.

We may be witnessing a similar revolution in our understanding of Alzheimer’s disease.

More here.

Whenever there’s a leak of documents from the remote islands and obscure jurisdictions where rich people hide their money, such as this week’s release of the

Whenever there’s a leak of documents from the remote islands and obscure jurisdictions where rich people hide their money, such as this week’s release of the  Hip-hop artist Childish Gambino (aka actor

Hip-hop artist Childish Gambino (aka actor  Not long after I moved into my first apartment, I started keeping an archive.

Not long after I moved into my first apartment, I started keeping an archive. Jonathan Franzen, the novelist who has been lauded and reviled as few figures in contemporary American letters ever are,

Jonathan Franzen, the novelist who has been lauded and reviled as few figures in contemporary American letters ever are,  Aaron Benanav in The Nation (Illustration by Tim Robinson):

Aaron Benanav in The Nation (Illustration by Tim Robinson):

Justin Sandefur over at the Center for Global Development:

Justin Sandefur over at the Center for Global Development: Yakov Feygin in Noema (image by Roman Bratschi for Noema Magazine):

Yakov Feygin in Noema (image by Roman Bratschi for Noema Magazine): David McDermott Hughes in Boston Review:

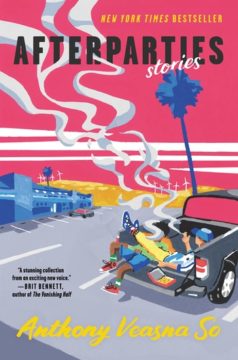

David McDermott Hughes in Boston Review: Afterparties is haunted by lateness, not only because it arrives after the premature death of its author, but also because it is a work of Cambodian American literature. “I very much feel that I come from a Cambodian-American world, not really an American one . . . so I find it important for my work to reflect that,” So said in a 2020 interview. In contrast to Asian American writing by those of Japanese, Chinese, and Korean descent (what So might refer to as “mainstream East Asians” in “The Shop”), Cambodian American writing is a relatively newer and more minor literature. (“We’re minorities within minorities,” goes So’s own self-description in his posthumous essay “Baby Yeah.”) There was a relative absence of Cambodian American communities until the late 1970s, following the genocide and the passage of the 1980 Refugee Act; there is now also a deficit of Cambodian writing and writers, because the Khmer Rouge annihilated Cambodian society by targeting its intellectuals and artists (libraries and schools were demolished, books burned, teachers murdered). The aftershocks of genocidal loss permeate the writing of the Cambodian diaspora, as the deliberate obliteration of their literature makes the work of contemporary writing both more necessary and difficult. For the children of Cambodian refugees, this work is even harder: How do you write the stories of those whose stories were systematically destroyed?

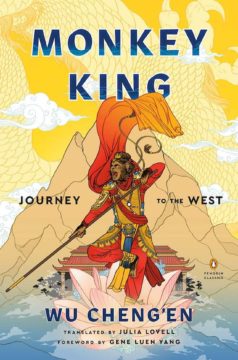

Afterparties is haunted by lateness, not only because it arrives after the premature death of its author, but also because it is a work of Cambodian American literature. “I very much feel that I come from a Cambodian-American world, not really an American one . . . so I find it important for my work to reflect that,” So said in a 2020 interview. In contrast to Asian American writing by those of Japanese, Chinese, and Korean descent (what So might refer to as “mainstream East Asians” in “The Shop”), Cambodian American writing is a relatively newer and more minor literature. (“We’re minorities within minorities,” goes So’s own self-description in his posthumous essay “Baby Yeah.”) There was a relative absence of Cambodian American communities until the late 1970s, following the genocide and the passage of the 1980 Refugee Act; there is now also a deficit of Cambodian writing and writers, because the Khmer Rouge annihilated Cambodian society by targeting its intellectuals and artists (libraries and schools were demolished, books burned, teachers murdered). The aftershocks of genocidal loss permeate the writing of the Cambodian diaspora, as the deliberate obliteration of their literature makes the work of contemporary writing both more necessary and difficult. For the children of Cambodian refugees, this work is even harder: How do you write the stories of those whose stories were systematically destroyed? Third, Monkey King accentuates one of the major appeals of the novel — its humor — with embellishments made by the translator in three main ways: dialogue, the culture of the immortal society, and the technicality of magic. Monkey is nothing without his complete disregard for formality, even (or especially) as he interacts with those perching at the top of the deities’ hierarchical system. He evokes both childish innocence and rebellious boldness. The English edition takes this characteristic and runs with it, tweaking a word choice here and perfecting a repartee there, in line with the lighthearted tone of the original. I should mention also that Lovell excels at spicing up the insults exchanged between Monkey and his enemies. One of the spirits sent to subdue Monkey threatens his monkey kingdom, “The merest whisper of resistance and we’ll turn the lot of you into baboon butter” — you will not find “baboon butter” in the original version.

Third, Monkey King accentuates one of the major appeals of the novel — its humor — with embellishments made by the translator in three main ways: dialogue, the culture of the immortal society, and the technicality of magic. Monkey is nothing without his complete disregard for formality, even (or especially) as he interacts with those perching at the top of the deities’ hierarchical system. He evokes both childish innocence and rebellious boldness. The English edition takes this characteristic and runs with it, tweaking a word choice here and perfecting a repartee there, in line with the lighthearted tone of the original. I should mention also that Lovell excels at spicing up the insults exchanged between Monkey and his enemies. One of the spirits sent to subdue Monkey threatens his monkey kingdom, “The merest whisper of resistance and we’ll turn the lot of you into baboon butter” — you will not find “baboon butter” in the original version. Let’s talk about fear, health and why so many of us have decided that sitting in front of the

Let’s talk about fear, health and why so many of us have decided that sitting in front of the  For the chance to escape severe debt, the characters in Netflix’s hugely popular survival drama Squid Game would risk anything, even death. Take the protagonist Seong Gi-hun. Unemployed, he spends his days in Seoul gambling on horse races and has signed away his organs as collateral to his creditors. His deficits, both financial and personal, hurt the people closest to him: He hasn’t paid child support or alimony to his ex-wife; he mooches off his elderly mother. On his daughter’s birthday, Gi-hun can afford to buy her only tteokbokki (spicy rice cakes) and a claw-machine toy. He has little left to lose.

For the chance to escape severe debt, the characters in Netflix’s hugely popular survival drama Squid Game would risk anything, even death. Take the protagonist Seong Gi-hun. Unemployed, he spends his days in Seoul gambling on horse races and has signed away his organs as collateral to his creditors. His deficits, both financial and personal, hurt the people closest to him: He hasn’t paid child support or alimony to his ex-wife; he mooches off his elderly mother. On his daughter’s birthday, Gi-hun can afford to buy her only tteokbokki (spicy rice cakes) and a claw-machine toy. He has little left to lose.