Suzanne O’Sullivan in Nautilus:

People who have psychologically mediated physical symptoms always fear being accused of feigning illness. I knew that one of the reasons Dr. Olssen was desperate for me to provide a brain-related explanation for the children’s condition was to help them escape such an accusation. She also knew that a brain disorder had a better chance of being respected than a psychological disorder. To refer to resignation syndrome as stress induced would lessen the seriousness of the children’s condition in people’s minds. It is the way of the world that the length of time a person spends as sick, immobile, and unresponsive is less impressive if it doesn’t come with a corresponding change on a brain scan.

People who have psychologically mediated physical symptoms always fear being accused of feigning illness. I knew that one of the reasons Dr. Olssen was desperate for me to provide a brain-related explanation for the children’s condition was to help them escape such an accusation. She also knew that a brain disorder had a better chance of being respected than a psychological disorder. To refer to resignation syndrome as stress induced would lessen the seriousness of the children’s condition in people’s minds. It is the way of the world that the length of time a person spends as sick, immobile, and unresponsive is less impressive if it doesn’t come with a corresponding change on a brain scan.

Not all the medical interest in this disorder has focused on blood tests and brain scans. More psychologically minded explanations have compared resignation syndrome to pervasive refusal syndrome (also called pervasive arousal withdrawal syndrome—PAWS), a psychiatric disorder of children and teens in which they resolutely refuse to eat, talk, walk, or engage with their surroundings. The cause is unknown, but PAWS has been linked to stress and trauma. The withdrawal in PAWS is an active one, as the word “refusal” suggests; it is not apathetic. Still, as a condition associated with hopelessness, it does seem to have more in common with resignation syndrome than other suggestions.

The resignation-syndrome children became ill while living in Sweden, but most had experienced trauma in their country of birth. It seems likely, then, that this past trauma would play a significant role in the illness. Perhaps it is a form of post-traumatic stress disorder? Or could the ordeals suffered by the parents have affected their ability to parent, which in turn impacted on the emotional development of the child? One psychodynamically minded theory is that the traumatized mothers are projecting their fatalistic anguish onto their children, in what one doctor described as an act of “lethal mothering.”

There is clearly much of value in investigating the biological and psychological explanations for resignation syndrome, but even when taken together they fall short. Psychological explanations focus too much on the stressor and on the mental state of the individual affected, without adequately paying attention to the bigger picture. They also come with the inevitable need to apportion blame, passing judgement on the child and the child’s family. They risk diminishing the family’s plight in the eyes of others. Psychological distress simply doesn’t elicit the same urgent need for help that physical suffering does.

More here.

The author of some of the most acclaimed works of the modern literary canon, including The Trial (1925), The Castle (1926), and The Metamorphosis (1915), was drawing and sketching extensively before he published a single word. Brod, Kafka’s closest friend and literary executor, held on to as many of the drawings as he could. When Kafka died in 1924, Brod famously disregarded the author’s instructions that everything was “to be burned, completely and unread.” He spent the rest of his life publishing and promoting Kafka’s work, and when he fled the Nazi occupation of Prague in 1939 for Palestine, he took Kafka’s papers and drawings with him. He published a small selection of the pictures in his biographical writings on Kafka and sold two of them to the Albertina in Vienna. Others appeared in Kafka’s diaries, today at the Bodleian Library at Oxford, which Brod edited for publication in 1948. This is all the world has known until now of Kafka’s art — scarcely 40 or so drawings and sketches from what was once a far larger corpus, much of it lost or destroyed, and the rest mostly invisible to the public until this year.

The author of some of the most acclaimed works of the modern literary canon, including The Trial (1925), The Castle (1926), and The Metamorphosis (1915), was drawing and sketching extensively before he published a single word. Brod, Kafka’s closest friend and literary executor, held on to as many of the drawings as he could. When Kafka died in 1924, Brod famously disregarded the author’s instructions that everything was “to be burned, completely and unread.” He spent the rest of his life publishing and promoting Kafka’s work, and when he fled the Nazi occupation of Prague in 1939 for Palestine, he took Kafka’s papers and drawings with him. He published a small selection of the pictures in his biographical writings on Kafka and sold two of them to the Albertina in Vienna. Others appeared in Kafka’s diaries, today at the Bodleian Library at Oxford, which Brod edited for publication in 1948. This is all the world has known until now of Kafka’s art — scarcely 40 or so drawings and sketches from what was once a far larger corpus, much of it lost or destroyed, and the rest mostly invisible to the public until this year.

Michael Knox Beran begins his exploration brutally by telling us that the WASPs are finished, quite dead. Edie Sedgwick, one of Andy Warhol’s muses, was the last desperate gasp of the WASPs, reduced to being brought to prominence (of a kind) by someone from Pittsburgh and then cruelly abandoned. She died of a drug overdose in 1971. Her father, Fuzzy, was bad enough, removing himself to California, where he turned his vast private estate into a version of the Playboy Mansion. The book goes backwards from there but things don’t get any better. Early on comes this extraordinary sentence: ‘There is … great difficulty in writing about people whose time has passed, who were bathed in the lukewarm bath of snobbery, who, with flashes of insight, were largely mediocre.’

Michael Knox Beran begins his exploration brutally by telling us that the WASPs are finished, quite dead. Edie Sedgwick, one of Andy Warhol’s muses, was the last desperate gasp of the WASPs, reduced to being brought to prominence (of a kind) by someone from Pittsburgh and then cruelly abandoned. She died of a drug overdose in 1971. Her father, Fuzzy, was bad enough, removing himself to California, where he turned his vast private estate into a version of the Playboy Mansion. The book goes backwards from there but things don’t get any better. Early on comes this extraordinary sentence: ‘There is … great difficulty in writing about people whose time has passed, who were bathed in the lukewarm bath of snobbery, who, with flashes of insight, were largely mediocre.’ Two years ago, to prepare for an unusual photo shoot, a team of scientists plucked the wings from thousands of fruit flies and pressed each flake of iridescent tissue between glass plates. As often as not, the wing tore or folded, or an air pocket or errant piece of dust got trapped along with it, ruining the sample. Fly wings are “not like Saran wrap,” said

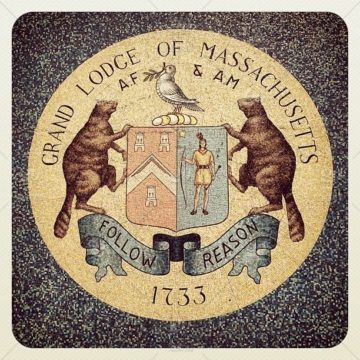

Two years ago, to prepare for an unusual photo shoot, a team of scientists plucked the wings from thousands of fruit flies and pressed each flake of iridescent tissue between glass plates. As often as not, the wing tore or folded, or an air pocket or errant piece of dust got trapped along with it, ruining the sample. Fly wings are “not like Saran wrap,” said  Rationality is uncool. To describe someone with a slang word for the cerebral, like nerd, wonk, geek, or brainiac, is to imply they are terminally challenged in hipness. For decades, Hollywood screenplays and rock-song lyrics have equated joy and freedom with an escape from reason. “A man needs a little madness or else he never dares cut the rope and be free,”

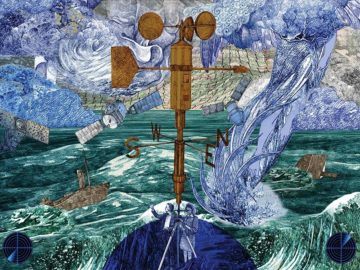

Rationality is uncool. To describe someone with a slang word for the cerebral, like nerd, wonk, geek, or brainiac, is to imply they are terminally challenged in hipness. For decades, Hollywood screenplays and rock-song lyrics have equated joy and freedom with an escape from reason. “A man needs a little madness or else he never dares cut the rope and be free,”  For centuries, humans complained about the weather. In 1848, the Smithsonian Institution decided to do something about it. Weather conditions had been considered to be either God’s will or explainable only by homespun nostrums like “Clear moon, frost soon” or by observing, say, the behavior of ants, which don’t like rain. The Farmer’s Almanac promised readers more accurate forecasts when it debuted in 1818, but even those predictions were determined by a “secret formula.” And still are.

For centuries, humans complained about the weather. In 1848, the Smithsonian Institution decided to do something about it. Weather conditions had been considered to be either God’s will or explainable only by homespun nostrums like “Clear moon, frost soon” or by observing, say, the behavior of ants, which don’t like rain. The Farmer’s Almanac promised readers more accurate forecasts when it debuted in 1818, but even those predictions were determined by a “secret formula.” And still are. As a young lieutenant, Daniel Kahneman was asked to improve the Israeli army’s haphazard process of assessing capabilities among combat-eligible recruits.

As a young lieutenant, Daniel Kahneman was asked to improve the Israeli army’s haphazard process of assessing capabilities among combat-eligible recruits. The medications, developed to treat and prevent viral infections in people and animals, work differently depending on the type. But they can be engineered to boost the immune system to fight infection, block receptors so viruses can’t enter healthy cells, or lower the amount of active virus in the body.

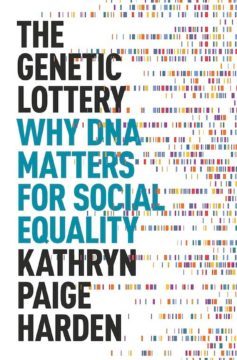

The medications, developed to treat and prevent viral infections in people and animals, work differently depending on the type. But they can be engineered to boost the immune system to fight infection, block receptors so viruses can’t enter healthy cells, or lower the amount of active virus in the body. DNA plays a major role, indeed a starring role, in generating socioeconomic inequality in the United States, according to Kathryn Paige Harden, a behavioral geneticist at the University of Texas. In her provocative new book, The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA Matters for Social Equality, she contends that our genes predispose us to getting more or less education, which then largely determines our place in the social order. This argument isn’t new. It has appeared perhaps most notoriously in Arthur Jensen’s infamous 1969 article in the Harvard Educational Review (

DNA plays a major role, indeed a starring role, in generating socioeconomic inequality in the United States, according to Kathryn Paige Harden, a behavioral geneticist at the University of Texas. In her provocative new book, The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA Matters for Social Equality, she contends that our genes predispose us to getting more or less education, which then largely determines our place in the social order. This argument isn’t new. It has appeared perhaps most notoriously in Arthur Jensen’s infamous 1969 article in the Harvard Educational Review ( C

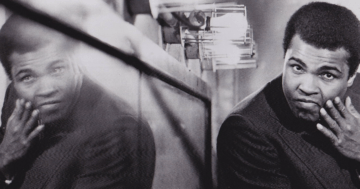

C There’s power in watching Ali exact his revenge against Ernie Terrell, who had refused to call him by his Muslim name prior to their fight, punishing Terrell in the ring as he repeatedly taunts him: “What’s my name?” As the essayist Gerald Early says, “It was a sign that a new kind of Black athlete had appeared, a whole new kind of Black consciousness had appeared—it was a whole new kind of Black male dispensation that had come about as a result of that fight. That fight to me and I think for many other young Black people such as myself at the time was a turning point.”

There’s power in watching Ali exact his revenge against Ernie Terrell, who had refused to call him by his Muslim name prior to their fight, punishing Terrell in the ring as he repeatedly taunts him: “What’s my name?” As the essayist Gerald Early says, “It was a sign that a new kind of Black athlete had appeared, a whole new kind of Black consciousness had appeared—it was a whole new kind of Black male dispensation that had come about as a result of that fight. That fight to me and I think for many other young Black people such as myself at the time was a turning point.” It’s National Inclusion Week when we all come together to ‘celebrate everyday inclusion in all its forms’. This year’s theme is ‘unity’ where ‘thousands of inclusioneers worldwide’ are being encouraged to ‘take action to be #UnitedForInclusion.’ In the bewildering world of identity politics, however, there is one group of excluded individuals you won’t be hearing much about. As a demographic, they suffer from all kinds of discrimination and yet social justice activists seem uninterested in their plight. Unlike oppressed minorities, this particular group may be in the majority and yet they garner little in the way of sympathy from anyone, barring their mums, perhaps.

It’s National Inclusion Week when we all come together to ‘celebrate everyday inclusion in all its forms’. This year’s theme is ‘unity’ where ‘thousands of inclusioneers worldwide’ are being encouraged to ‘take action to be #UnitedForInclusion.’ In the bewildering world of identity politics, however, there is one group of excluded individuals you won’t be hearing much about. As a demographic, they suffer from all kinds of discrimination and yet social justice activists seem uninterested in their plight. Unlike oppressed minorities, this particular group may be in the majority and yet they garner little in the way of sympathy from anyone, barring their mums, perhaps. People who have psychologically mediated physical symptoms always fear being accused of feigning illness. I knew that one of the reasons Dr. Olssen was desperate for me to provide a brain-related explanation for the children’s condition was to help them escape such an accusation. She also knew that a brain disorder had a better chance of being respected than a psychological disorder. To refer to resignation syndrome as stress induced would lessen the seriousness of the children’s condition in people’s minds. It is the way of the world that the length of time a person spends as sick, immobile, and unresponsive is less impressive if it doesn’t come with a corresponding change on a brain scan.

People who have psychologically mediated physical symptoms always fear being accused of feigning illness. I knew that one of the reasons Dr. Olssen was desperate for me to provide a brain-related explanation for the children’s condition was to help them escape such an accusation. She also knew that a brain disorder had a better chance of being respected than a psychological disorder. To refer to resignation syndrome as stress induced would lessen the seriousness of the children’s condition in people’s minds. It is the way of the world that the length of time a person spends as sick, immobile, and unresponsive is less impressive if it doesn’t come with a corresponding change on a brain scan. Almost every first draft (and third, and fifth) is overwritten. Maybe too much is happening, but usually it’s all the talk that bloats and clogs. Too much of anything at the outset can be helpful, though; every tailor knows it’s easier to cut cloth than to adhere it. But there is an art to cutting.

Almost every first draft (and third, and fifth) is overwritten. Maybe too much is happening, but usually it’s all the talk that bloats and clogs. Too much of anything at the outset can be helpful, though; every tailor knows it’s easier to cut cloth than to adhere it. But there is an art to cutting. US-based Azra Raza, a respected oncologist of Pakistani origin, has been treating cancer patients for around two decades. Her grouse, articulated in her book, The First Cell, is that most new drugs add mere months to one’s life, that too at great physical, financial and emotional cost. In her telling, the reason the war on cancer has reached an impasse is because doctors are essentially trying to protect the last cell, instead of checking the disease at birth. This has to change, and now, Raza writes with an evangelist’s passion.

US-based Azra Raza, a respected oncologist of Pakistani origin, has been treating cancer patients for around two decades. Her grouse, articulated in her book, The First Cell, is that most new drugs add mere months to one’s life, that too at great physical, financial and emotional cost. In her telling, the reason the war on cancer has reached an impasse is because doctors are essentially trying to protect the last cell, instead of checking the disease at birth. This has to change, and now, Raza writes with an evangelist’s passion. When the philosopher Amia Srinivasan’s essay “The Right to Sex” appeared in the London Review of Books, in 2018, it garnered a level of attention not usually paid to writing by academics. From the provocative title to the bracing clarity of the content (“Sex is not a sandwich,” Srinivasan wrote), the essay’s stylistic appeal was matched by a willingness to entertain positions that had long been off the table in both feminist and mainstream discussions of sex. The piece responded to the commentary surrounding Elliot Rodger, perhaps the most famous of the so-called incels, or involuntary celibates, who in 2014 killed six people after penning a 107,000-word manifesto that railed against the women who had deprived him of sex. Many feminists were quick to read Rodger as a case study in male sexual entitlement. Fewer wanted to broach one of the manifesto’s thornier claims: that Rodger, who was half white and half Malaysian Chinese, had been denied sex because of his race. Srinivasan took Rodger’s undesirability head-on: of course, no one has a right to be desired, she wrote. But we ought to acknowledge, as second-wave feminists more readily did, that who or what is desired is a political question, subject to scrutiny.

When the philosopher Amia Srinivasan’s essay “The Right to Sex” appeared in the London Review of Books, in 2018, it garnered a level of attention not usually paid to writing by academics. From the provocative title to the bracing clarity of the content (“Sex is not a sandwich,” Srinivasan wrote), the essay’s stylistic appeal was matched by a willingness to entertain positions that had long been off the table in both feminist and mainstream discussions of sex. The piece responded to the commentary surrounding Elliot Rodger, perhaps the most famous of the so-called incels, or involuntary celibates, who in 2014 killed six people after penning a 107,000-word manifesto that railed against the women who had deprived him of sex. Many feminists were quick to read Rodger as a case study in male sexual entitlement. Fewer wanted to broach one of the manifesto’s thornier claims: that Rodger, who was half white and half Malaysian Chinese, had been denied sex because of his race. Srinivasan took Rodger’s undesirability head-on: of course, no one has a right to be desired, she wrote. But we ought to acknowledge, as second-wave feminists more readily did, that who or what is desired is a political question, subject to scrutiny.