Category: Archives

Peter Williams (1952 – 2021) painter

Adalberto Álvarez (1948 – 2021) musician/composer

Winged Microchips Glide like Tree Seeds

Nikk Ogasa in Scientific American:

As spring ends, maple trees begin to unfetter winged seeds that flutter and swirl from branches to land gently on the ground. Inspired by the aerodynamics of these helicoptering pods, as well as other gliding, spinning tree seeds, engineers claim to have crafted the smallest ever wind-borne machines, which they call “microfliers.”

As spring ends, maple trees begin to unfetter winged seeds that flutter and swirl from branches to land gently on the ground. Inspired by the aerodynamics of these helicoptering pods, as well as other gliding, spinning tree seeds, engineers claim to have crafted the smallest ever wind-borne machines, which they call “microfliers.”

The largest versions of these winged devices, which the researchers sometimes refer to as “mesofliers” or “macrofliers,” are about two millimeters in length, roughly the size of a fruit fly. The smallest microfliers are a quarter that size. That makes them tiny enough to drift like seeds—but still large enough to tote compact microchips with sensors that gather information about the devices’ surroundings and wireless transmitters that send these data to scientists. Swarms of microfliers could be dropped from the sky to catch the wind and scatter across vast areas, says John Rogers, a physical chemist at Northwestern University. “Then you can exploit them as a network of sensors to map environmental contamination, disease spread, biohazards or other things,” he adds. Rogers and his colleagues describe the machines in a Nature paper published on Wednesday.

To help their contraptions descend as sedately and stably as possible, the engineers started by analyzing the shapes of airborne seeds such as those of big-leaf maples, box elders and woody vines in the genus Tristellateia. Then they used computers to simulate the airflow around similar shapes with slightly different geometries. This process allowed the researchers to refine a variety of designs until the microfliers fell even more steadily and slowly than their botanical counterparts.

More here.

‘How do I love thee?’ A Victorian-era poet finds liberation

Elizabeth Lund in The Christian Science Monitor:

During her lifetime, Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-61) was widely regarded as Britain’s best female poet. Her groundbreaking work helped sway public opinion against slavery and child labor and changed the direction of English-language poetry for generations. Yet within 70 years of her death, Barrett Browning was no longer viewed as an international literary superstar but as an invalid with a small, couch-bound life. By the 1970s, critics described her as lacking the talent of her husband, Robert Browning, and hindering his writing. Fiona Sampson challenges those views in “Two-Way Mirror: The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning,” the first new biography of the poet in more than 30 years. Sampson, whose works include the critically acclaimed biography “In Search of Mary Shelley,” reframes Barrett Browning’s reputation by highlighting her development as a writer despite the many restrictions she faced in Victorian society.

During her lifetime, Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-61) was widely regarded as Britain’s best female poet. Her groundbreaking work helped sway public opinion against slavery and child labor and changed the direction of English-language poetry for generations. Yet within 70 years of her death, Barrett Browning was no longer viewed as an international literary superstar but as an invalid with a small, couch-bound life. By the 1970s, critics described her as lacking the talent of her husband, Robert Browning, and hindering his writing. Fiona Sampson challenges those views in “Two-Way Mirror: The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning,” the first new biography of the poet in more than 30 years. Sampson, whose works include the critically acclaimed biography “In Search of Mary Shelley,” reframes Barrett Browning’s reputation by highlighting her development as a writer despite the many restrictions she faced in Victorian society.

As a child, Elizabeth Barrett – called “Ba” by her parents and 11 siblings – defied expectations. She penned her first poems at the age of 8 and began reading Homer, Shakespeare, and Milton, guided by her mother. For her 14th birthday, her father paid to have 50 copies printed of “The Battle of Marathon,” a 1,500-line moral tale she wrote in heroic couplets.

Her life changed profoundly a year later when she developed an illness that doctors tried to treat with prolonged bed rest and dangerous remedies, including opium. Despite her confinement, which would continue for most of her life, the young poet’s writing flourished. Her work was published, drawing the attention of two male mentors. One, like her father, encouraged her talent as well as submissive dependency on his guidance and approval.

More here.

Sunday Poem

Household

The tons of brick and stone, the yards of piping,

the sinks and china basins, three toilets, the tiles,

and the tons of wood in floors, chairs, tables,

the yards of flex and cable that wrap the house

like a net, the heavy glassed front door, the gate

onto the street, the rippled sheets of window,

the yew tree by the back, the pictures, books, piano:

what would it all weigh? One kiss, one breathed

declaration, and there it is: the mass of love.

by Henry Shukman

from the National Poetry Archive

An excerpt from Steven Pinker’s new book, “Rationality”

Steven Pinker in The Harvard Gazette:

How should we think of human rationality? The cognitive wherewithal to understand the world and bend it to our advantage is not a trophy of Western civilization; it’s the patrimony of our species. The San of the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa are one of the world’s oldest peoples, and their foraging lifestyle, maintained until recently, offers a glimpse of the ways in which humans spent most of their existence. Hunter-gatherers don’t just chuck spears at passing animals or help themselves to fruit and nuts growing around them. The tracking scientist Louis Liebenberg, who has worked with the San for decades, has described how they owe their survival to a scientific mindset. They reason their way from fragmentary data to remote conclusions with an intuitive grasp of logic, critical thinking, statistical reasoning, correlation and causation, and game theory.

How should we think of human rationality? The cognitive wherewithal to understand the world and bend it to our advantage is not a trophy of Western civilization; it’s the patrimony of our species. The San of the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa are one of the world’s oldest peoples, and their foraging lifestyle, maintained until recently, offers a glimpse of the ways in which humans spent most of their existence. Hunter-gatherers don’t just chuck spears at passing animals or help themselves to fruit and nuts growing around them. The tracking scientist Louis Liebenberg, who has worked with the San for decades, has described how they owe their survival to a scientific mindset. They reason their way from fragmentary data to remote conclusions with an intuitive grasp of logic, critical thinking, statistical reasoning, correlation and causation, and game theory.

More here.

Saturday, September 25, 2021

Why the Rich Get Richer and Interest Rates Go Down

Servaas Storm over at INET:

Servaas Storm over at INET:

In the waning days of August, in a world beset by the unending COVID19 public health crisis, by increasingly frequent extreme climate events, and by the terrible news from Afghanistan, the world’s central bankers, the rich, and the influential gathered (online) for the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s annual Jackson Hole symposium. The title of this year’s Economic Policy Symposium was “Macroeconomic Policy in an Uneven Economy.” Few observers were paying attention and most had low expectations, knowing that central bankers are caught in a catch-22: they cannot lower interest rates (already at the zero-lower bound) to boost the economy, and they cannot raise rates, because the current high private and public debts are sustainable only at very low interest rates. Likewise, central bankers are unable to discontinue their accommodative (QE) policies, because this would abruptly end the irrational exuberance in financial markets and risk another global financial crash. Indeed, Fed chair Jay Powell’s speech was predictably careful, cautiously outlining how the Fed will continue its accommodative policy, while steadily monitoring data for signs of persistent broad-based inflation. No news from the monetary policy front, in other words.

However, one of the contributions to the symposium, a paper by Atif Mian, Ludwig Straub, and Amir Sufi (2021), managed to make headlines in the New York Times and the Financial Times (amongst others). The authors argue that high income inequality is the cause, not the result, of the low natural rate of interest r* and high asset prices evident in recent years. “As the rich get richer in terms of income, it creates a saving glut,” Professor Mian told the New York Times, “The saving glut forces interest rates to fall, which makes the rich even wealthier. Inequality begets inequality. It is a vicious cycle, and we are stuck in it” (Irwin 2021).

More here.

Pleasure and Justice

Becca Rothfield in Boston Review:

Becca Rothfield in Boston Review:

One of the least interesting things a woman can do vis-à-vis sex is consent to it—yet lately, we seem to have less to say about female erotics than we do about male abuses.

On the one hand, it is not hard to understand why consent and its absence are at the forefront of mainstream conversation. A focus on rape and assault is warranted in a culture where sexual crimes are so tragically common: one in every six women in the United States is the victim of rape or attempted rape, and 81 percent of women have experienced some form of sexual harassment.

Still, hollow consent, unaccompanied by inner aching, is at least as ubiquitous as sexual coercion. Sex that is merely consensual is about as rousing as food that is merely edible, as drab as a cake without icing. Even in our era of ostensible liberation, women face emotional and social pressures, both externally imposed and uneasily internalized, to appease men at the cost of their own enjoyment. Heterosexual women are forever licensing liaisons that don’t excite them—perhaps because they have despaired of discovering anything as exotic as an exciting man, or because it no longer even occurs to them to insist on their own excitement, or because capitulation to unexciting men is so exhaustingly expected of them and so universally glorified in popular depictions of romance. As the formidable Oxford philosopher Amia Srinivasan writes in her debut essay collection, The Right to Sex, her female students regularly report that they regard their erotic lives as “at once inevitable and insufficient.” In short, the young women in Srinivasan’s classes are resigned to sex that is consensual but underwhelming.

More here.

Is Evergrande the New Lehman Brothers?

Adam Tooze at his podcast Ones and Tooze over at Foreign Policy:

Adam Tooze at his podcast Ones and Tooze over at Foreign Policy:

How did the Chinese real estate giant Evergrande become so laden with debt?

That question looms large these days, not only in China but also in other countries where markets have been affected by fears of Evergrande’s potential bankruptcy—including the United States.

On this week’s episode of Ones and Tooze, Cameron Abadi and Adam Tooze trace the history of Evergrande’s $300 billion debt problem and discuss the possible outcomes.

Tooze also explains why most wealthy countries around the world have bullet trains while the United States has… Amtrak.

Ones and Tooze is Foreign Policy’s weekly economics show. On each episode, Abadi and Tooze examine two data points that explain the world.

More here.

Sceptical Credulity

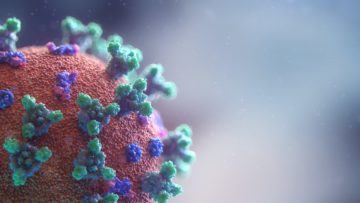

Marco D’Eramo in NLR’s Sidecar (Photo by Fusion Medical Animation on Unsplash):

Marco D’Eramo in NLR’s Sidecar (Photo by Fusion Medical Animation on Unsplash):

They looked at me with a benevolent smile, almost pitying my credulity, my capacity to be fooled. This person, whom I met by chance, was in their sixties, had taught at the Sorbonne and published several books. They immediately told me they would never get the Covid vaccine. They smiled when I objected that over the course of their life they had unthinkingly accepted over a dozen vaccines, from smallpox to polio, and that to enter a whole host of countries every one of us has been inoculated – against tetanus, yellow fever and so on – with relative serenity. ‘But this vaccine isn’t like the others,’ they replied, as if privy to information from which I had been shielded. At this point I understood that there was nothing I could say to shake their granitic certainty.

What struck me most, however, was their scepticism. I knew that if I entered into the conversation, at best we would have come to the issue of government deception and Big Pharma, at worst conspiracy theories about the microchips Bill Gates is supposedly implanting in the global population. Here we’re faced with a paradox: people believe in extraordinary tales precisely because of their sceptical disposition. Ancient credulity worked in a completely different manner to its contemporary equivalent. It was shared by the highest state authorities – who typically employed court astrologists – and the most downtrodden plebeians. Inquisitors believed in the reality of witchcraft, as did commoners, as did some of the accused witches themselves. In one sense the occult still functions this way in certain parts of postcolonial Africa, where the political class relies on the same rites as ordinary citizens, using witchcraft to perform some of the operations that are the purview of public relations departments in the so-called developed West. (Peter Geschiere’s 1997 text on this topic remains instructive: The Modernity of Witchcraft: Politics and the Occult in Postcolonial Africa). But, by and large, the modern world has given rise to a form of superstition that is accepted in the name of distrust towards the state and managerial classes.

More here.

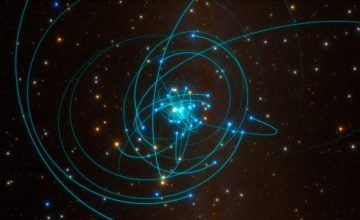

The Ecstasy of Scientific Discovery, and Its Agonizing Price

Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim in The New York Times:

In December 1915, while serving on the Russian front, the German astronomer and mathematician Karl Schwarzschild sent a letter to Albert Einstein that contained the first precise solution to the equations of general relativity. Schwarzschild’s approach had been simple. He had plugged Einstein’s equations into a model that posited an ideal, perfectly spherical star, in order to calculate how its mass would warp the surrounding space. Schwarzschild’s solution was elegant, but it revealed something monstrous: If the same process were applied not to an ideal star but to one that had begun to collapse, its density and gravity would increase infinitely, creating an enclosed region of space-time, or a singularity, from which nothing could escape. Schwarzschild had given the world its first glimpse of black holes.

In December 1915, while serving on the Russian front, the German astronomer and mathematician Karl Schwarzschild sent a letter to Albert Einstein that contained the first precise solution to the equations of general relativity. Schwarzschild’s approach had been simple. He had plugged Einstein’s equations into a model that posited an ideal, perfectly spherical star, in order to calculate how its mass would warp the surrounding space. Schwarzschild’s solution was elegant, but it revealed something monstrous: If the same process were applied not to an ideal star but to one that had begun to collapse, its density and gravity would increase infinitely, creating an enclosed region of space-time, or a singularity, from which nothing could escape. Schwarzschild had given the world its first glimpse of black holes.

In “When We Cease to Understand the World,” a gripping meditation on knowledge and hubris, Benjamín Labatut describes how Schwarzschild was seized by a sense of foreboding over his own discovery. “The true horror” of the singularity, he told a fellow mathematician, was that it created a “blind spot, fundamentally unknowable,” since even light would be unable to escape it. And what if, he continued, something similar could occur in the human psyche? “Could a sufficient concentration of human will — millions of people exploited for a single end with their minds compressed into the same psychic space — unleash something comparable to the singularity? Schwarzschild was convinced that such a thing was not only possible, but was actually taking place in the Fatherland.”

Schwarzschild, who was Jewish, did not live to see Hitler rise to power and concentrate the collective German will to catastrophic effect. But a different premonition came true within months. The “void without form or dimension,” which he told his wife had invaded his being, took shape as a rare disease that would cover his body in pustulant blisters and kill him mere months after his scientific breakthrough.

More here.

‘The Transgender Issue’ by Shon Faye

Shon Faye at The Guardian:

The Transgender Issue: An Argument for Justice, by Shon Faye, is not a relaxing read, and yet I am profoundly grateful that it exists. Nor is there all that much in it I didn’t already know, but then that is the nature of being a trans person in the UK. We are forced, in the name of self-defence, to become experts in every subject that might overlap with “the transgender issue”, from prisons to sports to public bathrooms. Meanwhile, many cisgender people live in blissful ignorance of the acute crises that face trans people in this country every day.

The Transgender Issue: An Argument for Justice, by Shon Faye, is not a relaxing read, and yet I am profoundly grateful that it exists. Nor is there all that much in it I didn’t already know, but then that is the nature of being a trans person in the UK. We are forced, in the name of self-defence, to become experts in every subject that might overlap with “the transgender issue”, from prisons to sports to public bathrooms. Meanwhile, many cisgender people live in blissful ignorance of the acute crises that face trans people in this country every day.

It is those people who really need to read this book. Faye lays out in unsparing detail the stark realities of trans life today. She makes sure, however, not to represent the trans condition as uniquely tragic or difficult, highlighting parallels between the trans experience and those of other oppressed or minority groups. This position is clear from the first line: “The liberation of trans people would improve the lives of everyone in our society.”

more here.

Wole Soyinka Is Not Going Anywhere

Ruth Maclean at the New York Times:

Wole Soyinka the firebrand activist is always getting Wole Soyinka the writer into trouble.

Wole Soyinka the firebrand activist is always getting Wole Soyinka the writer into trouble.

Like the time he held up a radio station to keep it from broadcasting what he said were fake election results, and got jailed for it. Or when he sneaked into Biafra at the height of its war for independence from Nigeria, and spent two years in solitary confinement after calling for an end to the fighting.

When the first Black winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature — and its first African winner — senses that things like freedom and democracy are under threat in the beloved nation whose history has intertwined with his own, he can’t help it. He has to get involved.

“It’s a temperament,” Soyinka, 87, said during an interview in Abeokuta, his hometown in southern Nigeria.

more here.

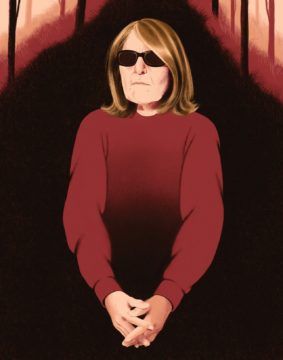

Joy Williams Does Not Write for Humanity

Katy Waldman at The New Yorker:

You don’t encounter the fiction of Joy Williams without experiencing a measure of bewilderment. Williams, one of the country’s best living writers of the short story, draws praise from titans such as George Saunders, Don DeLillo, and Lauren Groff, and many of her readers, having imprinted on her wayward phrasing and screwball characters, will follow her anywhere. But the route can be disorienting, like climbing an uneven staircase in a dream. Her tales offer a dark, provisional illumination, and they make the kind of sense that disperses upon waking. For years, Williams has worn sunglasses at all hours, as if to blacken her vision. The central subject of art, she has written, is “nothingness.”

You don’t encounter the fiction of Joy Williams without experiencing a measure of bewilderment. Williams, one of the country’s best living writers of the short story, draws praise from titans such as George Saunders, Don DeLillo, and Lauren Groff, and many of her readers, having imprinted on her wayward phrasing and screwball characters, will follow her anywhere. But the route can be disorienting, like climbing an uneven staircase in a dream. Her tales offer a dark, provisional illumination, and they make the kind of sense that disperses upon waking. For years, Williams has worn sunglasses at all hours, as if to blacken her vision. The central subject of art, she has written, is “nothingness.”

Williams is now seventy-nine. In her stories, and in her five novels, she opens cracks in reality, through which issue ghosts, clairvoyants, changelings, and suffering.

more here.

Saturday Poem

Upon Hearing the Glacier’s Been Declared Officially Dead

That hollering wind catches again

in my throat the way it once

caught at our tent all night it hasn’t

died down by morning blowing

open my mind’s shutters to that

interminable static snowfield ascent

with neither ropes nor poles

cold’s iron taste sunlight banging

like a gate in my sternum i grew old

expecting the crevasse-edge to crack

breakage i still carry in my pack

though years have fallen through us

and we’ve little occasion to speak

the glacier is dead news i zip

into a cool hidden pocket and keep

walking deforming and flowing

under the weight of zero gathering

a force that sucks the world we

knew through its infinite mouth

by Sara Burant

from the Echotheo Review, 9/21

Friday, September 24, 2021

Whither Tartaria?

Scott Alexander in Astral Codex Ten:

Imagine a postapocalyptic world. Beside the ruined buildings of our own civilization – St. Peter’s Basilica, the Taj Mahal, those really great Art Deco skyscrapers – dwell savages in mud huts. The savages see the buildings every day, but they never compose legends about how they were built by the gods in a lost golden age. No, they say they themselves could totally build things just as good or better. They just choose to build mud huts instead, because they’re more stylish.

This is the setup for my all-time favorite conspiracy theory, Tartaria. Its true believers say we are those savages. We live in the shadow of the Taj Mahal, Art Deco skyscrapers, etc. But our buildings look like this: [See photo.]

So (continues the conspiracy) probably we suffered some kind of apocalypse a hundred-ish years ago. Our elites are keeping it quiet, and have altered the records, but they haven’t been able to destroy all the buildings of the lost world. Their cover story is that technology and wealth level haven’t regressed or anything, those kinds of buildings have just “gone out of style”.

More here.

On making good predictions for 2050

Erik Hoel in The Intrinsic Perspective:

If you want to predict the future accurately, you should be an incrementalist and accept that human nature doesn’t change along most axes. Meaning that the future will look a lot like the past. If Cicero were transported from ancient Rome to our time he would easily understand most things about our society. There’d be a short-term amazement at various new technologies and societal changes, but soon Cicero would settle in and be throwing out Trump/Sulla comparisons (or contradicting them), since many of the debates we face, like what to do about growing wealth inequality, or how to keep a democracy functional, are the same as in Roman times.

If you want to predict the future accurately, you should be an incrementalist and accept that human nature doesn’t change along most axes. Meaning that the future will look a lot like the past. If Cicero were transported from ancient Rome to our time he would easily understand most things about our society. There’d be a short-term amazement at various new technologies and societal changes, but soon Cicero would settle in and be throwing out Trump/Sulla comparisons (or contradicting them), since many of the debates we face, like what to do about growing wealth inequality, or how to keep a democracy functional, are the same as in Roman times.

To see what I mean more specifically: 2050, that super futuristic year, is only 29 years out, so it is exactly the same as predicting what the world would look like today back in 1992. How would one proceed in such a prediction? Many of the most famous futurists would proceed by imagining a sci-fi technology that doesn’t exist (like brain uploading, magnetic floating cars, etc), with the assumption that these nonexistent technologies will be the most impactful. Yet what was most impactful from 1992 were technologies or trends already in their nascent phases, and it was simply a matter of choosing what to extrapolate.

More here.

Efforts to conduct war humanely have only perpetuated it

Anthony Dworkin in the Boston Review:

Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize during his first year in the White House, but he also became the first U.S. president to be at war during the entirety of his two terms in office. The irony of this contrast has often been noted. To historian and legal scholar Samuel Moyn, it represents more than a case of poor judgment by the Nobel committee—or, as others might see it, an example of how the toxic politics surrounding terrorism can blunt the best of intentions.

Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize during his first year in the White House, but he also became the first U.S. president to be at war during the entirety of his two terms in office. The irony of this contrast has often been noted. To historian and legal scholar Samuel Moyn, it represents more than a case of poor judgment by the Nobel committee—or, as others might see it, an example of how the toxic politics surrounding terrorism can blunt the best of intentions.

In his new book, Humane: How the United States Abandoned Peace and Reinvented War, Moyn argues that Obama lent his aura of reflective moral leadership to a form of displacement activity. Obama set U.S. militarism on a more principled footing, but the attention that his administration devoted to fighting according to unprecedently humane standards had the effect of legitimizing his pursuit of an indefinite military campaign against terrorist groups around the world. In this way, Moyn suggests, Obama represented the culmination of a long-gestating dynamic whereby the impulse to curb the brutality of war can perversely undermine efforts to rein in war itself.

More here.

Charlie Parker – Jam Session (1952)