Joseph M Keegin in Psyche:

Great art and thought have always been motivated by something other than mere moneymaking, even if moneymaking happened somewhere along the way. But our culture of instrumentality has settled like a thick fog over the idea that some activities are worth pursuing simply because they share in the beautiful, the good, or the true. No amount of birdwatching will win a person the presidency or a Beverly Hills mansion; making music with friends will not cure cancer or establish a colony on Mars. But the real project of humanity – of understanding ourselves as human beings, making a good world to live in, and striving together toward mutual flourishing – depends paradoxically upon the continued pursuit of what Hitz calls ‘splendid uselessness’.

Great art and thought have always been motivated by something other than mere moneymaking, even if moneymaking happened somewhere along the way. But our culture of instrumentality has settled like a thick fog over the idea that some activities are worth pursuing simply because they share in the beautiful, the good, or the true. No amount of birdwatching will win a person the presidency or a Beverly Hills mansion; making music with friends will not cure cancer or establish a colony on Mars. But the real project of humanity – of understanding ourselves as human beings, making a good world to live in, and striving together toward mutual flourishing – depends paradoxically upon the continued pursuit of what Hitz calls ‘splendid uselessness’.

The culture of the 21st century – on an increasingly planetary scale – is oriented around the practical principles of utility, effectiveness and impact. The worth of anything – an idea, an activity, an artwork, a relationship with another person – is determined pragmatically: things are good to the extent that they are instrumental, with instrumentality usually defined as the capacity to produce money or things.

More here.

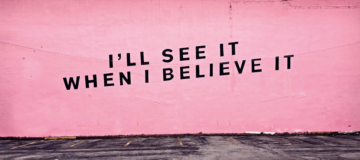

The biography of the actor Anthony Hopkins contains a striking example of a serendipitous coincidence. When he first heard he’d been cast to play a part in the film The Girl from Petrovka (1974), Hopkins went in search of a copy of the book on which it was based, a novel by George Feifer. He combed the bookshops of London in vain and, somewhat dejected, gave up and headed home. Then, to his amazement, he spotted a copy of The Girl from Petrovka lying on a bench at Leicester Square station. He recounted the story to Feifer when they met on location, and it transpired that the book Hopkins had stumbled upon was the very one that the author had mislaid in another part of London – an advance copy full of red-ink amendments and marginal notes he’d made in preparation for a US edition.

The biography of the actor Anthony Hopkins contains a striking example of a serendipitous coincidence. When he first heard he’d been cast to play a part in the film The Girl from Petrovka (1974), Hopkins went in search of a copy of the book on which it was based, a novel by George Feifer. He combed the bookshops of London in vain and, somewhat dejected, gave up and headed home. Then, to his amazement, he spotted a copy of The Girl from Petrovka lying on a bench at Leicester Square station. He recounted the story to Feifer when they met on location, and it transpired that the book Hopkins had stumbled upon was the very one that the author had mislaid in another part of London – an advance copy full of red-ink amendments and marginal notes he’d made in preparation for a US edition. Much has been written about the dramatic increase in income and wealth inequality in the United States over the last four decades. This volume of literature not only warns about the injustice of our current system, but also raises alarm that extreme inequality poses a serious risk to our democracy.

Much has been written about the dramatic increase in income and wealth inequality in the United States over the last four decades. This volume of literature not only warns about the injustice of our current system, but also raises alarm that extreme inequality poses a serious risk to our democracy. Know as we might

Know as we might  Throughout 1667, the ruins of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral became overgrown with a thicket of weeds. One yellow-flowered plant in particular mounted the walls in huge quantities. That spring, on the south side of the church, “

Throughout 1667, the ruins of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral became overgrown with a thicket of weeds. One yellow-flowered plant in particular mounted the walls in huge quantities. That spring, on the south side of the church, “ What is “creative nonfiction,” exactly? Isn’t the term an oxymoron? Creative writers—playwrights, poets, novelists—are people who make stuff up. Which means that the basic definition of “nonfiction writer” is a writer who doesn’t make stuff up, or is not supposed to make stuff up. If nonfiction writers are “creative” in the sense that poets and novelists are creative, if what they write is partly make-believe, are they still writing nonfiction? Biographers and historians sometimes adopt a narrative style intended to make their books read more like novels. Maybe that’s what people mean by “creative nonfiction”? Here are the opening sentences of a best-selling, Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of John Adams published a couple of decades ago:

What is “creative nonfiction,” exactly? Isn’t the term an oxymoron? Creative writers—playwrights, poets, novelists—are people who make stuff up. Which means that the basic definition of “nonfiction writer” is a writer who doesn’t make stuff up, or is not supposed to make stuff up. If nonfiction writers are “creative” in the sense that poets and novelists are creative, if what they write is partly make-believe, are they still writing nonfiction? Biographers and historians sometimes adopt a narrative style intended to make their books read more like novels. Maybe that’s what people mean by “creative nonfiction”? Here are the opening sentences of a best-selling, Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of John Adams published a couple of decades ago: After the Revolution in the United States, American society coalesced around controlling women’s behavior and sexual activity while exploiting their labor. Women’s “reduced rate,” or free labor in the case of slaves, was critical to the growing economy. And they were coerced, compelled, and conditioned to be meekly submissive. They were encouraged to “not expect too much”:

After the Revolution in the United States, American society coalesced around controlling women’s behavior and sexual activity while exploiting their labor. Women’s “reduced rate,” or free labor in the case of slaves, was critical to the growing economy. And they were coerced, compelled, and conditioned to be meekly submissive. They were encouraged to “not expect too much”:

In the movies the mathematician is always a lone genius, possibly mad, and uninterested in socializing with other people. Or they are

In the movies the mathematician is always a lone genius, possibly mad, and uninterested in socializing with other people. Or they are

Zaneb Beams. Untitled, 2022.

Zaneb Beams. Untitled, 2022.

‘Wenn möglich, bitte wenden.’

‘Wenn möglich, bitte wenden.’