Rachel Munroe in The New Yorker:

The federal raid on the Branch Davidian compound, thirty years ago, was flawed from the start. The Branch Davidians were a fringe offshoot of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and, in the early nineties, they were led by David Koresh, a charismatic long-haired man who believed that the end of days was imminent. The Davidians lived on a compound called Mount Carmel, twenty miles northeast of Waco, and were well known to local law enforcement, who considered them relatively benign.

The federal raid on the Branch Davidian compound, thirty years ago, was flawed from the start. The Branch Davidians were a fringe offshoot of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and, in the early nineties, they were led by David Koresh, a charismatic long-haired man who believed that the end of days was imminent. The Davidians lived on a compound called Mount Carmel, twenty miles northeast of Waco, and were well known to local law enforcement, who considered them relatively benign.

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms suspected the Davidians of illegally converting semi-automatic rifles into fully automatic weapons. (The weapons allegations seemed to inspire more reason for action than reports that Koresh was sexually assaulting his followers’ underage daughters.) During the ensuing investigation, A.T.F. agents repeatedly overestimated their capacity for subterfuge. When a group of undercover agents posing as college students moved into a house across the street from the Branch Davidian compound, their rental cars gave them away. The agents hosted a party to deflect suspicion, but it had the opposite effect: “Some of the Branch Davidians showed up, mingled, and reported back to Koresh that these were federal agents for sure,” Jeff Guinn writes, in the recently published “Waco: David Koresh, the Branch Davidians, and a Legacy of Rage.”

More here.

What is it about Rainer Maria Rilke? The influence of the Bohemian Austrian poet on modern culture reads like a who’s who of the great and the good. W. H. Auden, Cecil Day-Lewis, and Edith Sitwell claimed to be directly inspired by him. The first English translations of his work, published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press, became classics in their own right. He has been set to music (both classical and rock) and proven himself a Hollywood touchstone, most recently providing the

What is it about Rainer Maria Rilke? The influence of the Bohemian Austrian poet on modern culture reads like a who’s who of the great and the good. W. H. Auden, Cecil Day-Lewis, and Edith Sitwell claimed to be directly inspired by him. The first English translations of his work, published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press, became classics in their own right. He has been set to music (both classical and rock) and proven himself a Hollywood touchstone, most recently providing the  As I’ve mentioned before, economist, blogger, and friend Bryan Caplan was

As I’ve mentioned before, economist, blogger, and friend Bryan Caplan was  I hate preaching to the converted. If you were Buddhists, I’d

I hate preaching to the converted. If you were Buddhists, I’d  Twain bangs the keys—swiftly. For Remington’s levers, links, and triggers had made the typewriter resemble in kinetic spirit a kind of machine gun. Making writing rapid-fire, Remington turned a rather staid and quiet activity—writing—into one dominated by force and noise and physical effort. Sharp, metal characters smashed themselves against a platen, hitting with enough percussive force so that each letter impressed itself deeply into the paper. By 1881, with the introduction of the Remington II, a faster machine than its predecessor, sales exploded. From 1881 to 1890, typists increased in number from 5,000 to 33,400; and by 1900, according to census figures, America could boast 112,600 typists and stenographers. A good typist developed a distinctive rhythm, clacking out line after continuous line. A truly fast typist commanded attention. And respect. And sometimes even suspicion. At the Rosenberg spy trial, in 1952, the prosecuting attorney sharpened the government’s case against Ethel Rosenberg by asking the jury to visualize the female, Jewish suspect sitting behind her typewriter, “hitting the keys, blow by blow, against her own country in the interest of the Soviets.”

Twain bangs the keys—swiftly. For Remington’s levers, links, and triggers had made the typewriter resemble in kinetic spirit a kind of machine gun. Making writing rapid-fire, Remington turned a rather staid and quiet activity—writing—into one dominated by force and noise and physical effort. Sharp, metal characters smashed themselves against a platen, hitting with enough percussive force so that each letter impressed itself deeply into the paper. By 1881, with the introduction of the Remington II, a faster machine than its predecessor, sales exploded. From 1881 to 1890, typists increased in number from 5,000 to 33,400; and by 1900, according to census figures, America could boast 112,600 typists and stenographers. A good typist developed a distinctive rhythm, clacking out line after continuous line. A truly fast typist commanded attention. And respect. And sometimes even suspicion. At the Rosenberg spy trial, in 1952, the prosecuting attorney sharpened the government’s case against Ethel Rosenberg by asking the jury to visualize the female, Jewish suspect sitting behind her typewriter, “hitting the keys, blow by blow, against her own country in the interest of the Soviets.” EACH PHASE of research-based art presents a different understanding of what constitutes knowledge and a different approach to spectatorial labor. In the first phase, the artist invites the viewer to piece together parts from the materials provided to form their own historical narrative and to experience in their bodies and minds the complexity of a given (usually counterhegemonic) topic. Knowledge aspires to be new knowledge. In the second phase, the viewer listens to or reads a narrative crafted by the artist. Facts may be partly fictionalized, but there remains a sense of correcting or enhancing history, often through a counter- or micronarrative. The third phase returns the viewer to sifting through information, albeit now in a formal, less interactive mode. Knowledge is the aggregation of preexisting data, and the work accordingly invites meta-reflection on the production of knowledge as truth. In each case, though, despite creating the look or atmosphere of research, artists are reluctant to draw conclusions. Many of these pieces convey a sense of being immersed—even lost—in data.

EACH PHASE of research-based art presents a different understanding of what constitutes knowledge and a different approach to spectatorial labor. In the first phase, the artist invites the viewer to piece together parts from the materials provided to form their own historical narrative and to experience in their bodies and minds the complexity of a given (usually counterhegemonic) topic. Knowledge aspires to be new knowledge. In the second phase, the viewer listens to or reads a narrative crafted by the artist. Facts may be partly fictionalized, but there remains a sense of correcting or enhancing history, often through a counter- or micronarrative. The third phase returns the viewer to sifting through information, albeit now in a formal, less interactive mode. Knowledge is the aggregation of preexisting data, and the work accordingly invites meta-reflection on the production of knowledge as truth. In each case, though, despite creating the look or atmosphere of research, artists are reluctant to draw conclusions. Many of these pieces convey a sense of being immersed—even lost—in data. When the London newspaper the Athenian Mercury, edited and published by the author and bookseller John Dunton, first answered questions about romance, bodily functions, and the mysteries of the universe in 1691, it may have created the template for the advice column. But the history of advice stretches back even further into the past. Advice—whether unsolicited, unwarranted, or desperately sought—appears in ancient philosophical treatises, medieval medical manuals, and countless books. Lapham’s Quarterly is exploring advice through the ages and into modern times in a series of readings and essays.

When the London newspaper the Athenian Mercury, edited and published by the author and bookseller John Dunton, first answered questions about romance, bodily functions, and the mysteries of the universe in 1691, it may have created the template for the advice column. But the history of advice stretches back even further into the past. Advice—whether unsolicited, unwarranted, or desperately sought—appears in ancient philosophical treatises, medieval medical manuals, and countless books. Lapham’s Quarterly is exploring advice through the ages and into modern times in a series of readings and essays. One of the most astonishing passages in the Talmud, a book chock-full of astonishing passages, gingerly asks the question at the core of every single human pursuit: What, precisely, is the meaning of life?

One of the most astonishing passages in the Talmud, a book chock-full of astonishing passages, gingerly asks the question at the core of every single human pursuit: What, precisely, is the meaning of life? Once upon a time, when the famous scientist Albert Einstein worked at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, a tiny old woman approached him as he was walking home. She was schlepping a skinny young boy of about six who was dragging his feet.

Once upon a time, when the famous scientist Albert Einstein worked at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, a tiny old woman approached him as he was walking home. She was schlepping a skinny young boy of about six who was dragging his feet. There are plenty of uncertainties and unknowns around fusion energy, but on this question we can be clear. Since what we do about carbon emissions in the next two or three decades is likely to determine whether the planet gets just uncomfortably or catastrophically warmer by the end of the century, then the answer is no: fusion won’t come to our rescue. But if we can somehow scramble through the coming decades with makeshift ways of keeping a lid on global heating, there’s good reason to think that in the second half of the century fusion power plants will gradually help rebalance the energy economy.

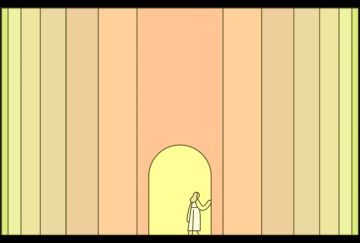

There are plenty of uncertainties and unknowns around fusion energy, but on this question we can be clear. Since what we do about carbon emissions in the next two or three decades is likely to determine whether the planet gets just uncomfortably or catastrophically warmer by the end of the century, then the answer is no: fusion won’t come to our rescue. But if we can somehow scramble through the coming decades with makeshift ways of keeping a lid on global heating, there’s good reason to think that in the second half of the century fusion power plants will gradually help rebalance the energy economy. One Friday night in October 2018, during the inaugural Palestinian Theatre Festival in Ramallah, I watched The Freedom Theatre from Jenin refugee camp perform a play called Return to Palestine. In this tightly choreographed 45-minute piece of physical comedy, a young Palestinian-American named Jad travels back to Jenin, a city in the northern West Bank, to visit his family for the first time. The black-clad ensemble of six forms a line that transforms fluidly into a car, a checkpoint, the entrance to the refugee camp, a café, accompanied by an oud, spoons and drums played by musicians sitting stage-right.

One Friday night in October 2018, during the inaugural Palestinian Theatre Festival in Ramallah, I watched The Freedom Theatre from Jenin refugee camp perform a play called Return to Palestine. In this tightly choreographed 45-minute piece of physical comedy, a young Palestinian-American named Jad travels back to Jenin, a city in the northern West Bank, to visit his family for the first time. The black-clad ensemble of six forms a line that transforms fluidly into a car, a checkpoint, the entrance to the refugee camp, a café, accompanied by an oud, spoons and drums played by musicians sitting stage-right. The focus of Audubon at Sea is indicated by its subtitle: The Coastal and Transatlantic Adventures of John James Audubon. It argues that he was never so comfortable at sea as he was on land when “collecting”—i.e., shooting—his specimens. Seabirds were harder to see up close, we are told; they are more elusive and maddening to approach, hence more enigmatic than land birds, at home in environments life-threatening to us. They were also uniquely disturbing to Audubon, the book’s editors Christoph Irmscher and Richard J. King argue, in their sheer abundance. They claim Audubon had no previous experience of such massive flocks, darkening the sky and crowding every inch of their breeding grounds, their guano heaped up like snow, filling the air with their deafening cries and vile stench. So there is a wry twist in the title’s phrase “at sea” (i.e., lost or confused) and in the subtitle’s “Adventures” (as if they were light-hearted!), which turn out to be—especially toward the end—when the story ventures into arctic waters and the terra incognita of Labrador—stories of seasickness, horrific gales, desolate wilderness, relentless rain and cold, with everything made worse by the depredations of men.

The focus of Audubon at Sea is indicated by its subtitle: The Coastal and Transatlantic Adventures of John James Audubon. It argues that he was never so comfortable at sea as he was on land when “collecting”—i.e., shooting—his specimens. Seabirds were harder to see up close, we are told; they are more elusive and maddening to approach, hence more enigmatic than land birds, at home in environments life-threatening to us. They were also uniquely disturbing to Audubon, the book’s editors Christoph Irmscher and Richard J. King argue, in their sheer abundance. They claim Audubon had no previous experience of such massive flocks, darkening the sky and crowding every inch of their breeding grounds, their guano heaped up like snow, filling the air with their deafening cries and vile stench. So there is a wry twist in the title’s phrase “at sea” (i.e., lost or confused) and in the subtitle’s “Adventures” (as if they were light-hearted!), which turn out to be—especially toward the end—when the story ventures into arctic waters and the terra incognita of Labrador—stories of seasickness, horrific gales, desolate wilderness, relentless rain and cold, with everything made worse by the depredations of men.