Dwight Garner in The New York Times:

Eleanor Catton’s third novel, “Birnam Wood,” is a big book, a sophisticated page-turner, that does something improbable: It filters anarchist, monkey-wrenching environmental politics, a generational (anti-baby boomer) cri de coeur and a downhill-racing plot through a Stoppardian sense of humor. The result is thrilling. “Birnam Wood” nearly made me laugh with pleasure. The whole thing crackles, like hair drawn through a pocket comb.

Eleanor Catton’s third novel, “Birnam Wood,” is a big book, a sophisticated page-turner, that does something improbable: It filters anarchist, monkey-wrenching environmental politics, a generational (anti-baby boomer) cri de coeur and a downhill-racing plot through a Stoppardian sense of humor. The result is thrilling. “Birnam Wood” nearly made me laugh with pleasure. The whole thing crackles, like hair drawn through a pocket comb.

Catton, who was born in Canada, raised in New Zealand and now lives in Cambridge, England, is a prodigy. She was, at 28, the youngest-ever recipient of the Booker Prize. She won it for “The Luminaries” (2013), a byzantine, dry-witted novel about irascible gold prospectors and unsolved crimes on New Zealand’s South Island in 1866. She is also the author of “The Rehearsal” (2008), a much slimmer novel, about a relationship between a male teacher and a student at an all-girls high school. Catton has felt like the real thing out of the gate. One reason is her way with dialogue. Her characters are almost disastrously candid. They talk the way real people talk, but they’re freer, ruder, funnier. Alongside the wordplay and in-jokes, and the topping of those jokes, unexpected abrasions pile up. You sense the world being thrashed out in front of your eyes.

Another reason is her knowingness — her thinginess. Catton is at home in the physical world, and her details land. (In “Birnam Wood” her scrimping gardeners strew hair-salon clippings as slug repellent.) Her books move sure-footedly, as if on gravel paths, between microclimates.

During the first century of our era, the Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca wrote to his friend Lucilius that life would be much happier if things would only decline as slowly as they grow. Unfortunately, as Seneca noted, “increases are of sluggish growth but the way to ruin is rapid.” We may call this universal rule the Seneca effect. Seneca’s idea that “ruin is rapid” touches something deep in our minds. Ruin, which we may also call “collapse,” is a feature of our world. We experience it with our health, our job, our family, our investments. We know that when ruin comes, it is unpredictable, rapid, destructive, and spectacular. And it seems to be impossible to stop until everything that can be destroyed is destroyed.

During the first century of our era, the Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca wrote to his friend Lucilius that life would be much happier if things would only decline as slowly as they grow. Unfortunately, as Seneca noted, “increases are of sluggish growth but the way to ruin is rapid.” We may call this universal rule the Seneca effect. Seneca’s idea that “ruin is rapid” touches something deep in our minds. Ruin, which we may also call “collapse,” is a feature of our world. We experience it with our health, our job, our family, our investments. We know that when ruin comes, it is unpredictable, rapid, destructive, and spectacular. And it seems to be impossible to stop until everything that can be destroyed is destroyed.

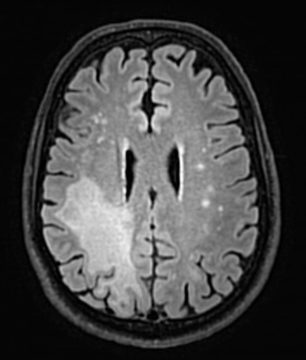

Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

Sughra Raza. NYC, April 2023.

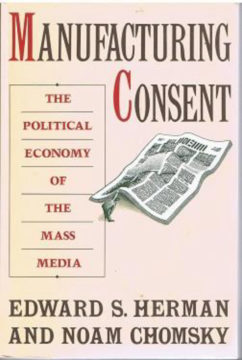

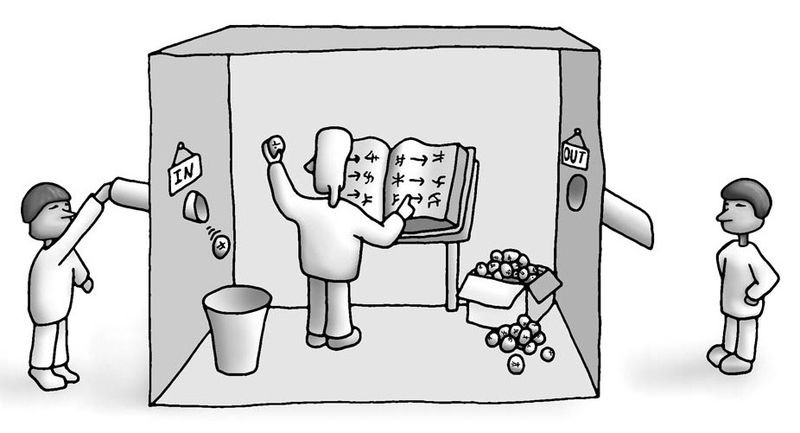

Despite many people’s apocalyptic response to ChatGPT, a great deal of caution and skepticism is in order. Some of it is philosophical, some of it practical and social. Let me begin with the former.

Despite many people’s apocalyptic response to ChatGPT, a great deal of caution and skepticism is in order. Some of it is philosophical, some of it practical and social. Let me begin with the former.

Whenever I’m feeling uninspired, I think: Somewhere, somebody is doing something right now. You may say this sounds less like a hype mantra and more like the mother of all mediocre movie taglines; you would not be wrong. Nevertheless, this thought is, for me, a surefire poem-generator—lifting me up, up, and away from the well-worn facticity of myself, out into the contemporaneous “Mysteries” of unknown others and their unknown lives.

Whenever I’m feeling uninspired, I think: Somewhere, somebody is doing something right now. You may say this sounds less like a hype mantra and more like the mother of all mediocre movie taglines; you would not be wrong. Nevertheless, this thought is, for me, a surefire poem-generator—lifting me up, up, and away from the well-worn facticity of myself, out into the contemporaneous “Mysteries” of unknown others and their unknown lives. From squabbling over who booked a disaster holiday to differing recollections of a glorious wedding, events from deep in the past can end up being misremembered. But now researchers say even recent memories may contain errors.

From squabbling over who booked a disaster holiday to differing recollections of a glorious wedding, events from deep in the past can end up being misremembered. But now researchers say even recent memories may contain errors. In the US and around the world, people are

In the US and around the world, people are  I remember attending a symposium on space science in Washington, DC, sometime in the 1990s, at which the head of NASA at the time, Dan Goldin, gave a keynote address. He marched up to the podium in his trademark cowboy boots, looked out at the assembled astronomers and physicists in the audience, and asked: “How many biologists are here today?” No hands went up. He then said, “The next time I address this audience, I expect it to be full of biologists!”

I remember attending a symposium on space science in Washington, DC, sometime in the 1990s, at which the head of NASA at the time, Dan Goldin, gave a keynote address. He marched up to the podium in his trademark cowboy boots, looked out at the assembled astronomers and physicists in the audience, and asked: “How many biologists are here today?” No hands went up. He then said, “The next time I address this audience, I expect it to be full of biologists!”