by Ali Minai

How intelligent is ChatGPT? That question has loomed large ever since OpenAI released the chatbot late in 2022. The simple answer to the question is, “No, it is not intelligent at all.” That is the answer that AI researchers, philosophers, linguists, and cognitive scientists have more or less reached a consensus on. Even ChatGPT itself will admit this if it is in the mood. However, it’s worth digging a little deeper into this issue – to look at the sense in which ChatGPT and other large language models (LLMs) are or are not intelligent, where they might lead, and what risks they might pose regardless of whether they are intelligent. In this article, I make two arguments. First, that, while LLMs like ChatGPT are not anywhere near achieving true intelligence, they represent significant progress towards it. And second, that, in spite of – or perhaps even because of – their lack of intelligence, LLMs pose very serious immediate and long-term risks. To understand these points, one must begin by considering what LLMs do, and how they do it.

How intelligent is ChatGPT? That question has loomed large ever since OpenAI released the chatbot late in 2022. The simple answer to the question is, “No, it is not intelligent at all.” That is the answer that AI researchers, philosophers, linguists, and cognitive scientists have more or less reached a consensus on. Even ChatGPT itself will admit this if it is in the mood. However, it’s worth digging a little deeper into this issue – to look at the sense in which ChatGPT and other large language models (LLMs) are or are not intelligent, where they might lead, and what risks they might pose regardless of whether they are intelligent. In this article, I make two arguments. First, that, while LLMs like ChatGPT are not anywhere near achieving true intelligence, they represent significant progress towards it. And second, that, in spite of – or perhaps even because of – their lack of intelligence, LLMs pose very serious immediate and long-term risks. To understand these points, one must begin by considering what LLMs do, and how they do it.

Not Your Typical Autocomplete

As their name implies, LLMs focus on language. In particular, given a prompt – or context – an LLM tries to generate a sequence of sensible continuations. For example, given the context “It was the best of times; it was the”, the system might generate “worst” as the next word, and then, with the updated context “It was the best of times; it was the worst”, it might generate the next word, “of” and then “times”. However, it could, in principle, have generated some other plausible continuation, such as “It was the best of times; it was the beginning of spring in the valley” (though, in practice, it rarely does because it knows Dickens too well). This process of generating continuation words one by one and feeding them back to generate the next one is called autoregression, and today’s LLMs are autoregressive text generators (in fact, LLMs generate partial words called tokens which are then combined into words, but that need not concern us here.) To us – familiar with the nature and complexity of language – this seems to be an absurdly unnatural way to produce linguistic expression. After all, real human discourse is messy and complicated, with ambiguous references, nested clauses, varied syntax, double meanings, etc. No human would concede that they generate their utterances sequentially, one word at a time. Read more »

There are plenty of uncertainties and unknowns around fusion energy, but on this question we can be clear. Since what we do about carbon emissions in the next two or three decades is likely to determine whether the planet gets just uncomfortably or catastrophically warmer by the end of the century, then the answer is no: fusion won’t come to our rescue. But if we can somehow scramble through the coming decades with makeshift ways of keeping a lid on global heating, there’s good reason to think that in the second half of the century fusion power plants will gradually help rebalance the energy economy.

There are plenty of uncertainties and unknowns around fusion energy, but on this question we can be clear. Since what we do about carbon emissions in the next two or three decades is likely to determine whether the planet gets just uncomfortably or catastrophically warmer by the end of the century, then the answer is no: fusion won’t come to our rescue. But if we can somehow scramble through the coming decades with makeshift ways of keeping a lid on global heating, there’s good reason to think that in the second half of the century fusion power plants will gradually help rebalance the energy economy.

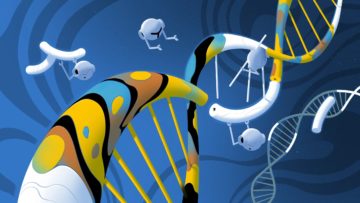

All animals, plants, fungi and protists — which collectively make up the domain of life called eukaryotes — have genomes with a peculiar feature that has puzzled researchers for almost half a century: Their genes are fragmented.

All animals, plants, fungi and protists — which collectively make up the domain of life called eukaryotes — have genomes with a peculiar feature that has puzzled researchers for almost half a century: Their genes are fragmented. Postcards from Absurdistan is the third volume in a ‘loose trilogy of cultural histories’ in which Derek Sayer has argued that European modernity is best examined from a vantage point located, both literally and figuratively, in Bohemia and its capital, Prague. The first volume, The Coasts of Bohemia (1998), tackled the issue of national identity. It presented Czech history – from its mythic beginnings to just after the communist takeover in 1948 – as a lesson on the nature of national historiography. When a ‘small’ nation has, for most of its past, struggled for recognition, its history is bound to consist of attempts to re-invent the past in order to assure itself of a future. The form of this reassurance: a bricolage of national treasures assembled largely under the motto ‘small but ours’. Focusing on the main tropes of the Czech National Revival – especially the emphasis on the Czech language as the basis for national identity, and the encoding of Czechness as something anti-German, anti-aristocratic and anti-Catholic – Sayer presents this chequered history as a corrective to the national histories of bigger, older, more secure nations. A lot of what he marks out as specifically Czech, however, sounds very familiar in the Irish context. None better than the Czechs at understanding Irish people’s fondness for the ‘best little country in the world’ trope (including its associated ironies) and the pitfalls of turning a language into a crux of nationality.

Postcards from Absurdistan is the third volume in a ‘loose trilogy of cultural histories’ in which Derek Sayer has argued that European modernity is best examined from a vantage point located, both literally and figuratively, in Bohemia and its capital, Prague. The first volume, The Coasts of Bohemia (1998), tackled the issue of national identity. It presented Czech history – from its mythic beginnings to just after the communist takeover in 1948 – as a lesson on the nature of national historiography. When a ‘small’ nation has, for most of its past, struggled for recognition, its history is bound to consist of attempts to re-invent the past in order to assure itself of a future. The form of this reassurance: a bricolage of national treasures assembled largely under the motto ‘small but ours’. Focusing on the main tropes of the Czech National Revival – especially the emphasis on the Czech language as the basis for national identity, and the encoding of Czechness as something anti-German, anti-aristocratic and anti-Catholic – Sayer presents this chequered history as a corrective to the national histories of bigger, older, more secure nations. A lot of what he marks out as specifically Czech, however, sounds very familiar in the Irish context. None better than the Czechs at understanding Irish people’s fondness for the ‘best little country in the world’ trope (including its associated ironies) and the pitfalls of turning a language into a crux of nationality. A Vindication was written in six weeks. On January 3, 1792, the day she gave the last sheet to the printer, Wollstonecraft wrote to Roscoe: “I am dissatisfied with myself for not having done justice to the subject.—Do not suspect me of false modesty—I mean to say that had I allowed myself more time I could have written a better book, in every sense of the word.” Wollstonecraft isn’t in fact being coy: her book isn’t well-made. Her main arguments about education are at the back, the middle is a sarcastic roasting of male conduct-book writers in the style of her attack on Burke, and the parts about marriage and friendship are scattered throughout when they would have more impact in one place. There is a moralizing, bossy tone, noticeably when Wollstonecraft writes about the sorts of women she doesn’t like (flirts and rich women: take a deep breath). It ends with a plea to men, in a faux-religious style that doesn’t play to her strengths as a writer. In this, her book is like many landmark feminist books—The Second Sex, The Feminine Mystique—that are part essay, part argument, part memoir, held together by some force, it seems, that is attributable solely to its writer. It’s as if these books, to be written at all, have to be brought into being by autodidacts who don’t know for sure what they’re doing—just that they have to do it.

A Vindication was written in six weeks. On January 3, 1792, the day she gave the last sheet to the printer, Wollstonecraft wrote to Roscoe: “I am dissatisfied with myself for not having done justice to the subject.—Do not suspect me of false modesty—I mean to say that had I allowed myself more time I could have written a better book, in every sense of the word.” Wollstonecraft isn’t in fact being coy: her book isn’t well-made. Her main arguments about education are at the back, the middle is a sarcastic roasting of male conduct-book writers in the style of her attack on Burke, and the parts about marriage and friendship are scattered throughout when they would have more impact in one place. There is a moralizing, bossy tone, noticeably when Wollstonecraft writes about the sorts of women she doesn’t like (flirts and rich women: take a deep breath). It ends with a plea to men, in a faux-religious style that doesn’t play to her strengths as a writer. In this, her book is like many landmark feminist books—The Second Sex, The Feminine Mystique—that are part essay, part argument, part memoir, held together by some force, it seems, that is attributable solely to its writer. It’s as if these books, to be written at all, have to be brought into being by autodidacts who don’t know for sure what they’re doing—just that they have to do it. Perhaps it took the roiling events that would give such a manic-depressive quality to 1963––the death in early June of Pope John XXIII (and with it, some feared, the demise of John’s policy of aggiornamento, “updating”); the signing of the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in August; the March on Washington the same month; and, in cruel culmination of the year’s roller-coaster ride, the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22––to open the ears (and hearts) of the American public, by year’s end emotionally spent, to the cheeky wit and fresh take on rock ‘n’ roll offered by the Beatles. As Rorem would observe, “Our need for [the Beatles] is…specifically a renewal, a renewal of pleasure.”

Perhaps it took the roiling events that would give such a manic-depressive quality to 1963––the death in early June of Pope John XXIII (and with it, some feared, the demise of John’s policy of aggiornamento, “updating”); the signing of the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in August; the March on Washington the same month; and, in cruel culmination of the year’s roller-coaster ride, the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22––to open the ears (and hearts) of the American public, by year’s end emotionally spent, to the cheeky wit and fresh take on rock ‘n’ roll offered by the Beatles. As Rorem would observe, “Our need for [the Beatles] is…specifically a renewal, a renewal of pleasure.” Thanks so much for speaking to us Nick, I wanted to start off by asking about the philosophical principles you use in the lab every day. Philosophers often see science as proposing a reductive theory of the world, breaking it down into its constituent parts. Some worry that this ignores the complexity of life. Do you think that this reduction plays a role in your work and science more broadly?

Thanks so much for speaking to us Nick, I wanted to start off by asking about the philosophical principles you use in the lab every day. Philosophers often see science as proposing a reductive theory of the world, breaking it down into its constituent parts. Some worry that this ignores the complexity of life. Do you think that this reduction plays a role in your work and science more broadly? While battles about what’s called the “woke left” now dominate political discussion in many countries, it’s time to ask whether woke really belongs on the left—or if woke represents a distortion of the core principles of the left, a drift into a philosophy of tribalism.

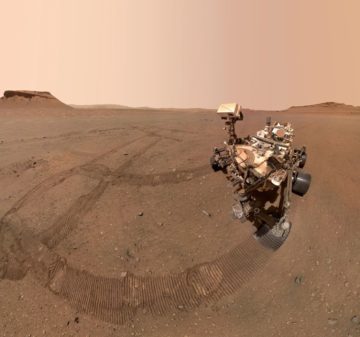

While battles about what’s called the “woke left” now dominate political discussion in many countries, it’s time to ask whether woke really belongs on the left—or if woke represents a distortion of the core principles of the left, a drift into a philosophy of tribalism. For decades, scientists who study Mars have watched in envy as spacecraft brought pieces of the Moon, chunks of asteroids and even samples of the solar wind to Earth to be studied. Now some of those researchers might finally be on track to receive rocks from the red planet — but only if NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) can pull off a complex and daring mission.

For decades, scientists who study Mars have watched in envy as spacecraft brought pieces of the Moon, chunks of asteroids and even samples of the solar wind to Earth to be studied. Now some of those researchers might finally be on track to receive rocks from the red planet — but only if NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) can pull off a complex and daring mission. How intelligent is ChatGPT? That question has loomed large ever since

How intelligent is ChatGPT? That question has loomed large ever since

Environmentalists are always complaining that governments are obsessed with GDP and economic growth, and that this is a bad thing because economic growth is bad for the environment. They are partly right but mostly wrong. First, while governments talk about GDP a lot, that does not mean that they actually prioritise economic growth. Second, properly understood economic growth is a great and wonderful thing that we should want more of.

Environmentalists are always complaining that governments are obsessed with GDP and economic growth, and that this is a bad thing because economic growth is bad for the environment. They are partly right but mostly wrong. First, while governments talk about GDP a lot, that does not mean that they actually prioritise economic growth. Second, properly understood economic growth is a great and wonderful thing that we should want more of. Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 1, 2023.

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 1, 2023.