Month: August 2022

The Advent Of Truly Urban Versions Of Wildlife Species

Darryl Jones at Culturico:

Cities are, indeed, the opposite of natural ecosystems. Net sinks of energy and materials, they are hot, noisy, poisonous and dangerous. They are constantly changing, often for frivolous or even wasteful reasons. Very few non-human species can cope with such chaos and stay away. Some species, however, see opportunities where others find only disturbance and stress. Cities offer countless productive chances for those willing and able to adapt. Those that take up this challenge share several crucial characteristics, including: already being abundant in the neighbouring landscape (10), having a generalised diet (with granivores being at a great advantage given the ubiquity of feeders)(11), demonstrating innovative foraging capacity and often belonging to groups with proportionally larger brains (12). Clearly, the latter two features go hand in hand.

Cities are, indeed, the opposite of natural ecosystems. Net sinks of energy and materials, they are hot, noisy, poisonous and dangerous. They are constantly changing, often for frivolous or even wasteful reasons. Very few non-human species can cope with such chaos and stay away. Some species, however, see opportunities where others find only disturbance and stress. Cities offer countless productive chances for those willing and able to adapt. Those that take up this challenge share several crucial characteristics, including: already being abundant in the neighbouring landscape (10), having a generalised diet (with granivores being at a great advantage given the ubiquity of feeders)(11), demonstrating innovative foraging capacity and often belonging to groups with proportionally larger brains (12). Clearly, the latter two features go hand in hand.

One additional characteristic, however, can be regarded as a prerequisite for making the first steps into a human-dominated environment: the ability to tolerate the presence of humans.

more here.

Henrietta Maria: Conspirator, Warrior, Phoenix Queen

Lucy Hughes-Hallett at Literary Review:

She was daughter, sister, wife or mother to five kings and two queens. On her wedding day, her pale blue velvet train was ostensibly held by three princesses of the blood, but so heavily encrusted was it with golden embroidery that a man had to walk concealed beneath it to carry the weight. Such a start in life might seem to presage a pleasant existence of leisure and luxury, but the career of Henrietta Maria, a Bourbon princess by birth and a Stuart queen by marriage, was as full of trouble and strife as the most harrowing of hard-luck case histories.

She was daughter, sister, wife or mother to five kings and two queens. On her wedding day, her pale blue velvet train was ostensibly held by three princesses of the blood, but so heavily encrusted was it with golden embroidery that a man had to walk concealed beneath it to carry the weight. Such a start in life might seem to presage a pleasant existence of leisure and luxury, but the career of Henrietta Maria, a Bourbon princess by birth and a Stuart queen by marriage, was as full of trouble and strife as the most harrowing of hard-luck case histories.

When she was six months old, her father, King Henri IV of France, was murdered. When she was seven, her eldest brother, who believed himself to be God’s representative on earth, had her mother arrested and banished from court.

more here.

the power of collective cognition

Steven Poole in The Guardian:

Intelligence – at least according to IQ test scores – is declining across the globe, which won’t surprise anyone who follows the news but doesn’t exactly bode well for the continuing survival on the species. What to do? One suggestion made by this book is that we all connect our brains to neural interfaces which will collect everyone’s thoughts in a massive “super-brain cloud”, the better to sweetly reason ourselves collectively out of disaster. What could possibly go wrong? This isn’t yet feasible anyway, but it is an example of the neuroscientist author’s determined optimism. Her central argument is important and correct: that we have become too used to thinking of intelligence as the private skill of individuals, vying against one another in a neoliberal world of relentless competition. What is needed, especially in an age of irredentist warmongering and climate disaster, is a greater emphasis on our ability to reason together, our “collective intelligence”.

Intelligence – at least according to IQ test scores – is declining across the globe, which won’t surprise anyone who follows the news but doesn’t exactly bode well for the continuing survival on the species. What to do? One suggestion made by this book is that we all connect our brains to neural interfaces which will collect everyone’s thoughts in a massive “super-brain cloud”, the better to sweetly reason ourselves collectively out of disaster. What could possibly go wrong? This isn’t yet feasible anyway, but it is an example of the neuroscientist author’s determined optimism. Her central argument is important and correct: that we have become too used to thinking of intelligence as the private skill of individuals, vying against one another in a neoliberal world of relentless competition. What is needed, especially in an age of irredentist warmongering and climate disaster, is a greater emphasis on our ability to reason together, our “collective intelligence”.

This has been possible, of course, since we gruntingly taught one another how to make flint tools around the cave fire. What does neuroscience add to our understanding of it?

More here.

Cancer’s Got a Lot of Nerve

Lina Zeldovich in Nautilus:

Manish Vira, a urologist at Northwell Health in New York performs prostate biopsy procedures three to five times a week. He inserts 12 needles into specific locations on the prostate gland, identified by MRI images that reveal malignant or suspicious lesions. The samples then go to a pathologist who determines whether cancer is present and how aggressive it is. “It’s a standard protocol,” explains Vira, who is also a chief oncologist at Northwell.

Manish Vira, a urologist at Northwell Health in New York performs prostate biopsy procedures three to five times a week. He inserts 12 needles into specific locations on the prostate gland, identified by MRI images that reveal malignant or suspicious lesions. The samples then go to a pathologist who determines whether cancer is present and how aggressive it is. “It’s a standard protocol,” explains Vira, who is also a chief oncologist at Northwell.

For the past few years, however, that standard protocol had a few extra steps. Now, the biopsy “wash”—a collection of molecules washed off the sample—goes to the research lab of Lloyd Trotman, a professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, who studies what makes these tumors aggressive or aids their metastases. Trotman’s team looks at the tumors’ genomic signatures—their genetic make-up, which can make them more aggressive. They look at the tumors’ microenvironments—the molecules that cancer surrounds itself with. And while researching these factors, they also dig into something that’s rarely looked at in cancer biology: the nervous system and its role in helping tumors spread.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Swoon

The ear that hears the cardinal

hears in red;

the eye that spots the salmon

sees in wet.

My senses always fall in love:

they spin, swoon;

they lose themselves in one

another’s arms.

Your senses live alone

like bachelors,

like bitter, slanted rhymes whose

marriage is a sham.

They greet the world the way accountants

greet their books.

I tire of such mastery. And yet, my senses

often fail

to let me do the simplest things,

like walk outside.

Invariably, the sun invades

my ears

and terrifies my feet—the angular

assault of Heaven’s

heavy-metal chords.

I cannot hear

to see, cannot see to move.

And so I cling,

As on a listing ship at night,

to the stair-rail.

Inequality, Justice, and Economics

by Raji Jayaraman

In the last two decades the topic of inequality has entered the public discourse across a broad spectrum of issues, with an urgency that is astonishing. To name but a few examples, the Occupy movement has called for more income equality, Black Lives Matter protesters have demand racial equality, women’s advocates have rallied behind causes as varied as equal pay and reproductive rights , and environmental activists have advocated for climate justice.

Surprisingly, economists are not front and centre of this discussion. I say “surprisingly” because economists are supposed to be the experts on inequality: they measure and study it. I think the reason why economists have not played a more central role in this discussion is that the protesters in today’s mass demonstrations are not just pointing out the existence of inequality. They are saying: “inequality is unjust”. With a few notable exceptions, however, today’s empirical economists don’t talk about justice. I fear that if economists don’t incorporate justice into their analysis, they risk losing relevance.

Why don’t applied economists who deal with data and policy design, speak of justice in a meaningful way? I think it boils down to four fundamental axioms that will be familiar to every economist. First, allocations must be efficient. Second, evidence must be data-driven. Third, policies should be forward-looking. Fourth, choices are made “at the margin”. As I explain below, I believe that these are very useful axioms. I also think, however, that they make it very hard for empirical economists who study inequality to effectively participate in the current debate on justice. In what follows, I explain why, using the four examples of protest movements to illustrate the crux of the problem. Read more »

Why Taxation Is Not Theft

by Thomas R. Wells

The idea that ‘taxation is theft’ is one of those thrilling, paradigm shifting recognitions that are continually being rediscovered and shared. It is a classic case of pseudo-intellectuality, in which the excitement around an idea determines its popularity, rather than its quality (previously).

First, unlike theft, taxation is legal – and this turns out to be a more significant difference than it first seems since we rely on laws to determine who owns what. Second, taxation is a device for solving collective action problems and thus allowing us (by coercing us) to meet our moral obligations to ourselves and each other – including our obligations to respect each others’ property rights. One can’t coherently be in favour of enforcing property rights, e.g. by having a police force and judges to catch and punish thieves, without also being in favour of a sustainable system for funding that enforcement.

1. Taxation is Legal

The straightforward rebuttal of the claim that taxation is theft goes like this:

- Theft is when someone takes something from you in a way that violates your legal property rights

- When the government taxes money from you they do not violate your legal property rights

Therefore - Taxation is not theft

To many people this semantic analysis is rather unsatisfactory. Whether things are legal or not is after all determined by the government. But whether something is right or wrong is determined by morality, which is not something determined by governments. The point of the claim that taxation is theft is that taxation is immoral in just the same way that theft is, i.e. that taking people’s property from them against their will and under threat of violence is wrong whether it is done by an ordinary person or by an agent of the government. Read more »

Monday Poem

Mystical Sects & Fractals

so many spinning sects exist with

peculiar angles

facts of life: all human things exist

alongside phantom gods and angels

a billion mystical takes on Is exist

like fractured fractals

as guesswork insistently persists

heads spin off their axles

Jim Culleny

5/6/16

The Tragedy of Ignorance

by Ada Bronowski

The encounter between Oedipus and the Sphinx has always represented the encounter between two incompatible worlds: chaos versus reason, myth versus history, woman against man, enigmatic verbosity against crystal-clear clarity. Only one of these worlds can survive the clash.

The Sphinx’s riddle: what stays the same yet walks on four feet in the morning, two at midday and three in the evening, is solved by Oedipus who says that it is man, who crawls on all four as a baby, walks on two feet in his prime and with the aid of a stick, and thus on three legs, in his old-age. With this answer, Oedipus came to his own not as Oedipus, the individual, but as a figure of modern man, dispelling the forces of darkness that reigned terror on helpless mortals. Overcoming the Sphinx was – it seemed – like a new beginning, in which man-made laws became the one true law, and wild nature was tamed by human rationality.

As the Sphinx threw itself off a cliff, it buried with it the unwieldly, monstrous side of nature, and Oedipus was hailed not as ‘one amongst the gods’ as so often with Greek heroes, but ‘as a mortal, first amongst men, who disarmed the supernatural forces’, (at the beginning of Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, l.31-4). Of course, we know what happened next. Man-made law and order did not stand a chance in the face of parricide, incest and children that are also siblings. The dark forces soon took hold of Oedipus and of Thebes once more, to the extent that one suspects they never left in the first place. Read more »

Antarctica and the People Who Write Their Names on It

by Rebecca Baumgartner

Apsley Cherry-Garrard, the Antarctic explorer who would become famous for documenting Robert Falcon Scott’s expedition in his book The Worst Journey in the World, wrote a letter in 1919 in which he cast doubt on the purity of the motives of one of the expedition members, Lieutenant Edward “Teddy” Evans: “There will…be an unprinted reference to the Antarctic as a white wall upon which some people have a passion for writing their names. If the cap fits let him put it on.”

Photograph by: Elaine Hood/National Science Foundation (NSF) License: Public Domain

One of the fascinating things about Antarctica is how its extreme conditions put the best and worst of humanity into stark relief. From the very beginning, the motives of the people going there have been multi-layered, an adulterated mix of ego, commercial incentive, scientific curiosity, wanderlust, and the siren call of the unknown. Even Cherry-Garrard himself, not having any training or scientific skill to speak of but coming from money, ended up buying his way onto Scott’s team. Geographic landmarks were routinely named after sponsors and backers of various expeditions. The very earliest journeys were motivated entirely by a money-making desire to kill as many seals and whales as possible. One member of Scott’s team was photographed happily eating a tin of Heinz Baked Beans as part of a sponsorship deal. There has never been a time when commercialization wasn’t a major part of the Antarctic enterprise. And it’s likely to stay that way, simply due to the sheer difficulty and expense of getting there in the first place and equipping yourself to survive once there. Read more »

Perceptions

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in The November Sun, 2020.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in The November Sun, 2020.

Digital photograph.

Can Any Theory of Knowledge Save Us From Conspiracy Theories?

by Joseph Shieber

I had my piece for 3QD all prepared at the beginning of the past week, but a phone call on Monday derailed my plans.

Early Monday morning, I received an email from the Philosophy Department administrative assistant saying that someone had left their name and phone number on the Philosophy Department’s answering machine with the request that I call them. I was curious, so I did.

I reached their voicemail, left my name and number, and they soon called back. They told me that they were concerned for a close family relative who had fallen down a QAnon rabbit-hole. Why were they calling me? Because their close family relative was appealing to my Great Courses lectures on epistemology in support of their views. The caller wanted to know, did my lectures in fact endorse QAnon?

Reader, let me begin by stressing at the outset that my lectures do NOT endorse QAnon.

With that out of the way, let me introduce some fake names for my caller and their family member – let’s make the caller “Avery” and the family member “Harper”. (I’m withholding as many details as I can to protect the caller’s privacy and in that spirit I’ve chosen gender neutral names.)

I began by telling Avery that it’s very common for conspiracy theorists of all stripes to latch onto – and misread – the work of experts. I continued by stressing that Harper’s appeal to my Great Courses lectures for support is clearly a misreading. Read more »

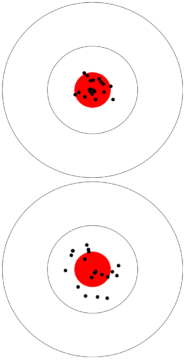

Natural Magic: On Weird Beliefs As Overfitting

by Jochen Szangolies

The world is a noisy place. No, I don’t mean the racket the neighbor’s kids are making in the back yard. Rather, I mean that, whatever you encounter in the world, probably isn’t exactly what’s actually there.

Let me explain. Suppose you’re fixing yourself a nice cocktail to enjoy on the porch in the sun (if those kids ever quiet down, that is). The recipe calls for 50 ml of vodka. You’re probably not going to measure out the exact amount drop by drop with a volumetric pipette; rather, maybe you use a measuring cup, or if you’ve got some experience (or this isn’t your first), you might just eyeball it.

But this will introduce unavoidable variations: you might pour a dash too much, or too little. Each such variation means that this particular Moscow Mule differs from the one before, and the one after—each is a slight variation on the ‘Moscow Mule’-theme. Recognizably the same, yet slightly different.

This difference is what is meant by ‘noise’: statistical variations in the measured value of a quantity due to inescapable limits to precision. For most everyday cases, noise matters comparatively little; but if you overshoot too much, your Mule might pack more kick than intended, and either just taste worse, or even make you yell at those pesky kids for harshing your mellow.

Thus, noise can have real-world consequences. Moreover, virtually everything is noisy: not just simple estimations of measurable quantities, like volumes, sizes, or time spans, but also less easily quantifiable items, like decisions or judgments. The latter is the topic of Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment, the new book by economy Nobel laureate Daniel Kahnemann, together with legal scholar Cass Sunstein and strategy expert Olivier Sibony. The book contains many striking examples of how noisy judgment leads to wide variance in fields like criminal sentencing, college admissions, or job recruitment. Thus, whether you get the job or go to jail might come down to little more than random variation, in extreme cases.

But noise has another effect that, I want to argue, can shed some light on why so many people seem to hold weird beliefs: it can make the correct explanation seem ill-suited to the evidence, and thus, favor an incorrect one that appears to fit better. Let’s look at a simple example. Read more »

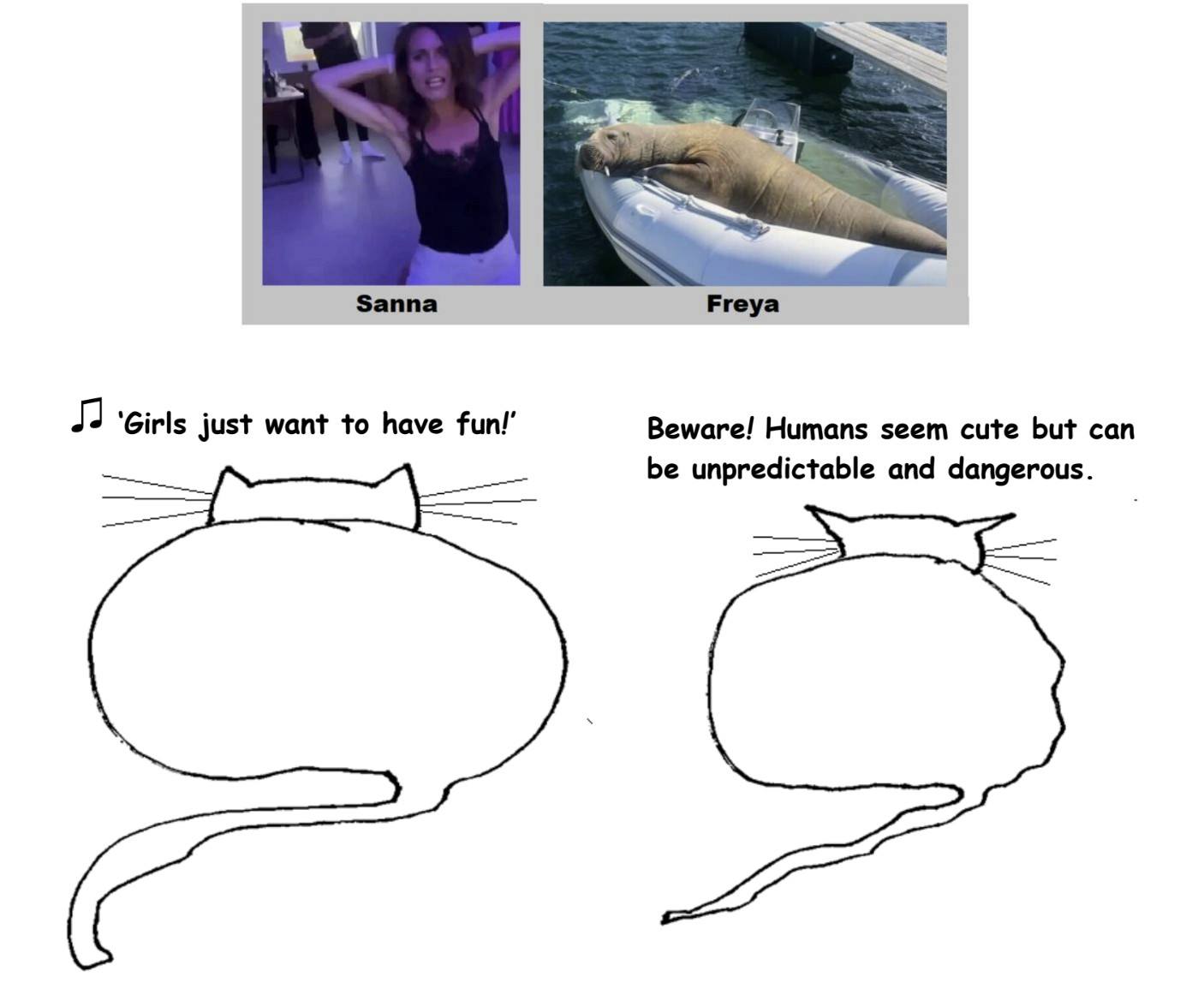

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Bad Latin

by Michael Abraham

I want to write about Christ and the End of the World and how queerness will usher in the World to Come. I want to write about these things immediately, right up front, but, instead, I will begin by telling you the story of two tattoos on my own body. I will begin this way because the story of these two tattoos has themes in it, and images in it. Themes and images are always a little murky, a little slippery. You have to write in circles to catch a theme, have to enter the circle of an image and be consumed there. You have to begin elsewhere than where you mean to be. So, I will tell the silly, little story of these two tattoos that I got as a teenager, and, after that, we will have themes and images. And once we have some themes and some images, it will be time to play with them, to twist and stretch them, to try to be creative in the sense of the eros: creative, to make, to bring forth. We will bring forth the End of the World and the World to Come and the indefatigability of the queer as an immanent force of transitionality in history. We will make these things real in our dual-action of writing and reading. But, first, the silly, little tattoo story.

***

I am sixteen, a year in which quite a lot happens to me. But one of the many things that happens when I am sixteen is that I decide I want a tattoo, and I want it on my wrist so that everyone can see it. I tell my mother this repeatedly, and she is understandably trepidatious, since how is one to trust a sixteen-year-old with a permanent decision. She comes to a solution finally, which is that I can have a tattoo if we get tattoos, the same tattoos, together. She is excited to share something significant with me, and I am excited about that too, but I am mostly excited to be the first kid in Catholic school with a tattoo. It is on a family trip to Kauai that we meet up with an old surfer bum tattoo artist on the North Shore in his beach shack tattoo studio, which I think he also lived in. By the time we get to the studio, I have given a lot of thought to the tattoo that I want. I know I want it to be words, for language, even then, matters deeply to me. However, I am a rather pretentious sixteen-year-old, so I want my tattoo to be in Latin. I have chosen the phrase “to the sea always” since both my mother and I are lovers of the ocean. Google Translate tells me that “to the sea always” in Latin is AD MARE SEMPER. So, the surfer bum tattoos AD MARE SEMPER on my wrist, facing towards me so that I can read it to myself, and on my mother’s leg. Read more »

Lush Life

by Dick Edelstein

Although jazz pianist, composer, arranger and lyricist Billy Strayhorn died in 1967 at the age of 51, his obscure life has since then become much better known than it was during his lifetime. His songs remain popular, and his reputation has continued to grow. Strayhorn shares credit for many jazz tunes he composed and arranged in collaboration with Duke Ellington and contributed without credit to others, such as the popular “Satin Doll”, but none of these tunes illustrate his importance and success as a jazz composer better than “Lush Life” and “Take the A Train”. The latter not only became the theme song of the Ellington orchestra but also one of its greatest successes and an anthem of the swing era. The lyrics of this song came from notes that Strayhorn took when he came to New York to work for Ellington for the first time, when he was only 23 years old. Ellington had given him directions on the easiest way to get to his house in Harlem – by taking the A train. The song has gone on to become one of the great jazz tunes both in its version with lyrics and as an instrumental.

Let’s consider one of Strayhorn’s most popular compositions, Lush Life, recorded by dozens of jazz artists over the years, and in recent years by Lady Gaga and Queen Latifa. For many jazz fans, one of the most memorable recordings of this song is the John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman version on their album released by Impulse! in 1963, which was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2000. Most of the lyrics were written when Strayhorn was still in high school, living in Pittsburgh. In a world-weary tone, the lyrics speak of night life following a failed romance. They represent a young boy’s fantasy about a sophisticated life seen from the point of view of a jaded bon vivant. Remarkably, they also describe the sort of life that, against all odds, Strayhorn was eventually to lead. Read more »

Monday Photo

Connecting Two Worlds: On Karl Ove Knausgaard’s “Spring”

by Derek Neal

Going back and reading one’s favorite authors is like seeing an old friend after a long absence: things fall into place, you remember why it is you get along with and like the other person, and their idiosyncrasies and unique character reappear and interact with your own, making old patterns reemerge and lighting up parts of you that have long been dormant.

Going back and reading one’s favorite authors is like seeing an old friend after a long absence: things fall into place, you remember why it is you get along with and like the other person, and their idiosyncrasies and unique character reappear and interact with your own, making old patterns reemerge and lighting up parts of you that have long been dormant.

Most, if not all my favorite authors, simply write and re-write the same book over and over again. This is often leveled as a criticism, but it is also a compliment. It means that the author in question has developed an individual voice and style that is present in all their works, often being refined over successive books until they eventually write the book that they’ve been trying to write in previous attempts, and this emerges, like a pearl, as the culmination of a lengthy process.

These were the thoughts I had upon recently reading Karl Ove Knausgaard’s novel/memoir/letter Spring, published in English in 2018. I guess the appropriate publishing term for Knausgaard’s writing is “autofiction,” but it doesn’t really matter, Knausgaard just writes about his life and looks at himself and his actions with such unflinching honesty, and the world around him with such open and sincere curiosity and attention—also characteristic of his My Struggle series—that he is one of those writers who merits his own adjective—Knausgaardian, or Knausgaardesque, or perhaps people today would say Knausgaardy, although this feels flippant and inappropriate, so I’ll go with Knausgaardesque, also because I like the resonance it has with how Kafka’s style is Kafkaesque. Read more »

Charaiveti: Journey From India To The Two Cambridges And Berkeley And Beyond, Part 58

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

The western admirers of Amartya Sen as a public intellectual may not be aware that he is actually in a long line of globally engaged cultural elite that Bengal has produced. (This is true to some extent of the elite elsewhere in India as well, particularly around Chennai and Mumbai, but I think in sheer scale over the last two hundred years, Bengal may have a special claim). One aspect of this phenomenon is worth reflecting on. These members of the cultural elite were well-versed in the manifold offerings of the West, but they came to them with a solid grounding in the cultural wealth of India. Take Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833). He was, as Nehru describes him in his Discovery of India, “deeply versed in Indian thought and philosophy, a scholar of Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic, ..a product of the mixed Hindu-Muslim culture, …the world’s first scholar of the science of Comparative Religion.” He contributed to the development of Bengali prose. He was a social reformer in Hindu society, actively engaged in serious religious debates with Christian missionaries in India, and a champion of women’s rights and freedom of press (standing up against colonial censorship). Yet when he went to England he caused some stir as the urbane face of a reforming Indian society, was active in campaigning for the 1832 Reform Act as a step to British democracy. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham reportedly even began a campaign to elect him to the British Parliament (but Roy caught meningitis and died in Bristol soon after). Read more »

The western admirers of Amartya Sen as a public intellectual may not be aware that he is actually in a long line of globally engaged cultural elite that Bengal has produced. (This is true to some extent of the elite elsewhere in India as well, particularly around Chennai and Mumbai, but I think in sheer scale over the last two hundred years, Bengal may have a special claim). One aspect of this phenomenon is worth reflecting on. These members of the cultural elite were well-versed in the manifold offerings of the West, but they came to them with a solid grounding in the cultural wealth of India. Take Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833). He was, as Nehru describes him in his Discovery of India, “deeply versed in Indian thought and philosophy, a scholar of Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic, ..a product of the mixed Hindu-Muslim culture, …the world’s first scholar of the science of Comparative Religion.” He contributed to the development of Bengali prose. He was a social reformer in Hindu society, actively engaged in serious religious debates with Christian missionaries in India, and a champion of women’s rights and freedom of press (standing up against colonial censorship). Yet when he went to England he caused some stir as the urbane face of a reforming Indian society, was active in campaigning for the 1832 Reform Act as a step to British democracy. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham reportedly even began a campaign to elect him to the British Parliament (but Roy caught meningitis and died in Bristol soon after). Read more »