Gideon Lasco in Sapiens:

In fact, all of the world’s chili peppers—including the labuyo peppers that we typically use in the Philippines—likely came from the first domesticated chili plants (Capsicum annuum) in what is now Mexico. They were imported as part of the Columbian exchange, which saw the two-way transfer of ideas, animals, plants, diseases, and people between the Eastern Hemisphere and the Americas following Christopher Colombus’ first transatlantic voyage in the late 15th century.

In fact, all of the world’s chili peppers—including the labuyo peppers that we typically use in the Philippines—likely came from the first domesticated chili plants (Capsicum annuum) in what is now Mexico. They were imported as part of the Columbian exchange, which saw the two-way transfer of ideas, animals, plants, diseases, and people between the Eastern Hemisphere and the Americas following Christopher Colombus’ first transatlantic voyage in the late 15th century.

Unthinkable as it may sound today, the cuisines we have come to associate with spiciness—Indian, Thai, Korean, and Chinese, among others—had no chili peppers at all before their introduction in the 16th century onward. Prior to that, those cuisines relied on other spices or aromatics to add heat to dishes, such as ginger, likely native to southern China, or black pepper, native to India.

How did chili peppers become part of the human diet beginning in the Americas an estimated 6,000 to 10,000 years ago? And why were they eventually embraced by the rest of the world?

More here.

It is Viktor Orbán’s worst nightmare: “One morning Anders, a white man, woke up to find he had turned a deep and undeniable brown.” It is the opening line to Mohsin Hamid’s new novel

It is Viktor Orbán’s worst nightmare: “One morning Anders, a white man, woke up to find he had turned a deep and undeniable brown.” It is the opening line to Mohsin Hamid’s new novel  Researchers are

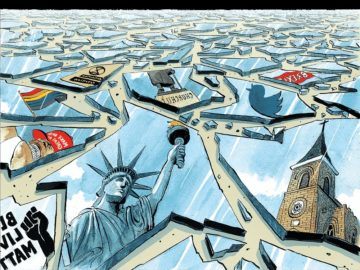

Researchers are  The main argument against prosecuting Donald Trump — or investigating him with an eye toward criminal prosecution — is that it will worsen an already volatile fracture in American society between Republicans and Democrats. If, before an indictment, we could contain the forces of political chaos and social dissolution, the argument goes, in the aftermath of such a move we would be at their mercy. American democracy might not survive the stress.

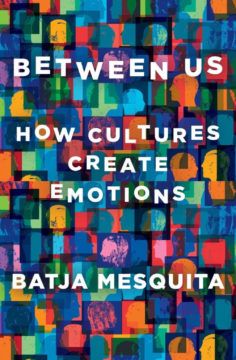

The main argument against prosecuting Donald Trump — or investigating him with an eye toward criminal prosecution — is that it will worsen an already volatile fracture in American society between Republicans and Democrats. If, before an indictment, we could contain the forces of political chaos and social dissolution, the argument goes, in the aftermath of such a move we would be at their mercy. American democracy might not survive the stress. For many years, psychologists and other scientists believed that deep down, all of humankind experienced the same set of evolutionarily hard-wired emotions. Under this schema, anger, for example, was a concrete, immutable experience that happens deep inside all human beings, the same for a White American sipping coffee in Manhattan as for native Siberian herding reindeer. When Batja Mesquita, a key figure in the development of the field of cultural psychology, started researching emotion more than 30 years ago, she was confident that this model was correct. But Mesquita, who is today a distinguished professor at the University of Leuven in Belgium, has come to view emotions through a completely different lens. In her new book, “

For many years, psychologists and other scientists believed that deep down, all of humankind experienced the same set of evolutionarily hard-wired emotions. Under this schema, anger, for example, was a concrete, immutable experience that happens deep inside all human beings, the same for a White American sipping coffee in Manhattan as for native Siberian herding reindeer. When Batja Mesquita, a key figure in the development of the field of cultural psychology, started researching emotion more than 30 years ago, she was confident that this model was correct. But Mesquita, who is today a distinguished professor at the University of Leuven in Belgium, has come to view emotions through a completely different lens. In her new book, “ This time a year ago,

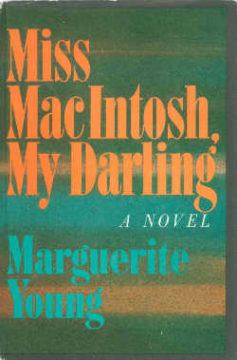

This time a year ago,  MARGUERITE YOUNG SPENT EIGHTEEN YEARS

MARGUERITE YOUNG SPENT EIGHTEEN YEARS I am against August. When I try to explain this position, some people instinctively want to argue. These people seem to love the beach beyond all reason, to have never suffered a yellowed pit stain on a favorite white T-shirt in their life, and to eagerly welcome all thirty-one days of August as though they are a reward for a year well-lived rather than a final trial before the beginning of another. These are people who vacation with peace of mind. To them, I say: Go away. To the people who agree with me, I say: Go on.

I am against August. When I try to explain this position, some people instinctively want to argue. These people seem to love the beach beyond all reason, to have never suffered a yellowed pit stain on a favorite white T-shirt in their life, and to eagerly welcome all thirty-one days of August as though they are a reward for a year well-lived rather than a final trial before the beginning of another. These are people who vacation with peace of mind. To them, I say: Go away. To the people who agree with me, I say: Go on. If the point of publishing a book is to have a public relations campaign, Will MacAskill is the greatest English writer since Shakespeare. He and his book

If the point of publishing a book is to have a public relations campaign, Will MacAskill is the greatest English writer since Shakespeare. He and his book  On a sweltering day in July, Yoshii Aya, still reeling from her bitter election defeat a few months prior, arrived in Kyoto with a stack of leftover business cards tailored for that bygone race. During a three-day political training camp for women trying to break into Japan’s male-dominated politics, she coyly passed them out as a “memento of my candidacy.” Had she won the April election, Ms. Yoshii would have become one of two women sitting on the 20-member city council in Miyoshi, Japan. Instead, she spent her summer reflecting on the loss, and learning campaign financing and social media strategy along with 15 other training camp participants. Ms. Yoshii says she felt empowered by connecting with like-minded women at the camp, which was organized by Tokyo’s Academy for Gender Parity.

On a sweltering day in July, Yoshii Aya, still reeling from her bitter election defeat a few months prior, arrived in Kyoto with a stack of leftover business cards tailored for that bygone race. During a three-day political training camp for women trying to break into Japan’s male-dominated politics, she coyly passed them out as a “memento of my candidacy.” Had she won the April election, Ms. Yoshii would have become one of two women sitting on the 20-member city council in Miyoshi, Japan. Instead, she spent her summer reflecting on the loss, and learning campaign financing and social media strategy along with 15 other training camp participants. Ms. Yoshii says she felt empowered by connecting with like-minded women at the camp, which was organized by Tokyo’s Academy for Gender Parity. A 6-year-old boy began hearing voices coming from the walls and the school intercom telling him to hurt himself and others. He saw ghosts, aliens in trees, and colored footprints. Joseph Gonzalez-Heydrich, MD, a psychiatrist at Boston Children’s Hospital, put him on antipsychotic medications and the frightening hallucinations stopped. Another child, at age 4, had hallucinations with monsters, a big black wolf, spiders, and a man with blood on his face.

A 6-year-old boy began hearing voices coming from the walls and the school intercom telling him to hurt himself and others. He saw ghosts, aliens in trees, and colored footprints. Joseph Gonzalez-Heydrich, MD, a psychiatrist at Boston Children’s Hospital, put him on antipsychotic medications and the frightening hallucinations stopped. Another child, at age 4, had hallucinations with monsters, a big black wolf, spiders, and a man with blood on his face. Does anyone still need advice on how not to think like a liberal? Amid widespread doubts on both left and right about the legitimacy of liberal institutions and economic arrangements, it might appear that the new book by Raymond Geuss, an American-born Cambridge University professor of philosophy, has come to tell us how not to do what we have already ceased doing. Yet as Geuss observes, “Some form of liberalism”—with its characteristic emphasis on uncoerced consent and open discussion among notionally free individuals—“is…still the basic framework which structures political, economic, and social thought in the English-speaking world.” So deeply embedded are liberal ideas in our institutions and discourse, he writes, that even when the conditions that gave rise to them have altered, “it can be difficult for someone who does not have a slightly deviant social position or education to get an appropriate cognitive distance from them, and thus to see some of their deficiencies for what they are.” Not Thinking Like a Liberal tells how its author came to acquire such deviancy.

Does anyone still need advice on how not to think like a liberal? Amid widespread doubts on both left and right about the legitimacy of liberal institutions and economic arrangements, it might appear that the new book by Raymond Geuss, an American-born Cambridge University professor of philosophy, has come to tell us how not to do what we have already ceased doing. Yet as Geuss observes, “Some form of liberalism”—with its characteristic emphasis on uncoerced consent and open discussion among notionally free individuals—“is…still the basic framework which structures political, economic, and social thought in the English-speaking world.” So deeply embedded are liberal ideas in our institutions and discourse, he writes, that even when the conditions that gave rise to them have altered, “it can be difficult for someone who does not have a slightly deviant social position or education to get an appropriate cognitive distance from them, and thus to see some of their deficiencies for what they are.” Not Thinking Like a Liberal tells how its author came to acquire such deviancy. The Covid-19 pandemic has killed an estimated fifteen million people around the world, ravaged health systems, and destroyed economies. It has also exposed destabilizing divisions at home and abroad, and revealed domestic and global weaknesses in biodefense. The United States alone has seen a million lives lost to the virus and an estimated

The Covid-19 pandemic has killed an estimated fifteen million people around the world, ravaged health systems, and destroyed economies. It has also exposed destabilizing divisions at home and abroad, and revealed domestic and global weaknesses in biodefense. The United States alone has seen a million lives lost to the virus and an estimated  What usually happens is this: some academic or other thinker or creative type is cheerfully chugging along in their career, living and working in progressive spaces. Maybe he is a professor, maybe he is a TV writer. Then, he commits some offence, or is perceived as having done so, and suddenly faces an onslaught of censure. Sometimes the opprobrium is wildly disproportionate to the offence. And there’s a very real walls-closing-in feeling, because the hate is coming from people he viewed as members of his ‘tribe,’ sometimes friends or close colleagues.

What usually happens is this: some academic or other thinker or creative type is cheerfully chugging along in their career, living and working in progressive spaces. Maybe he is a professor, maybe he is a TV writer. Then, he commits some offence, or is perceived as having done so, and suddenly faces an onslaught of censure. Sometimes the opprobrium is wildly disproportionate to the offence. And there’s a very real walls-closing-in feeling, because the hate is coming from people he viewed as members of his ‘tribe,’ sometimes friends or close colleagues.