by Mary Hrovat

This summer I noticed that I was sharing a lot of sunset photos on social media. I don’t think of myself as a photographer, and I’m much more likely to share words than images. When I thought about it, I realized this wasn’t a sudden change. I’ve been taking the odd set of sunset pictures with my Canon every now and then, and I’ve noticed that my eyes are increasingly drawn to the sky and the light when I look at landscape photos.

This summer I noticed that I was sharing a lot of sunset photos on social media. I don’t think of myself as a photographer, and I’m much more likely to share words than images. When I thought about it, I realized this wasn’t a sudden change. I’ve been taking the odd set of sunset pictures with my Canon every now and then, and I’ve noticed that my eyes are increasingly drawn to the sky and the light when I look at landscape photos.

And I’ve always loved the sky. It holds so many fascinating things: light, color, clouds, weather. Trees, birds. Moon, planets, stars. Time itself, and change. I like to walk at twilight, when the world is shifting from day to night, so it’s natural that sunsets would become a focus. This spring a friend gave me an old iPhone to use as a camera; it’s easy to carry with me, so I’ve been taking more pictures.

But I can’t really understand why I’m so utterly captivated by the colors of the sky, and their subtle gradations and changes. I feel as if I can never spend too much time just looking, at the sky and at other people’s images of it, and at plants, birds, bugs… . When I try to describe the strong desire to soak up as many experiences of nature as I can, to sense the colors and shapes as deeply as I can, I feel like I’m trying to explain a cannabis-induced insight: Everything is so beautiful! It feels kind of like craving, but not in an itchy unsatisfied way. In her poem “Born Into a World Knowing,” Susan Griffin wrote about hoping for a gentle death, “perhaps in someone’s arms, perhaps tasting chocolate…or saying not yet. Not yet the sky has at this moment turned another shade of blue.” There is always another shade of blue. Read more »

Being in Berkeley for more than four decades I have met and encountered many leftists and several of them are/were radical in their politics, though in recent years the radical fervor has been somewhat on the decline even in Berkeley. I remember some time back reading one east-coast journalist describing Berkeley, with a pinch of exaggeration, as moving from being the Left capital of the US to being its gourmet capital—this transition is, of course, most well-known in the case of Alice Waters who, a Berkeley activist in the 1960’s, started her iconic restaurant Chez Panisse in the next decade, though she herself considers the novel approach to food embodied in that restaurant—insistence on fresh ingredients and cooperative relations with local farmers– as growing out of the same counter-culture movement. (This transition was, of course, much more agreeable than some of the militant Black Panther leaders of 1960’s Oakland turning to Christian evangelism).

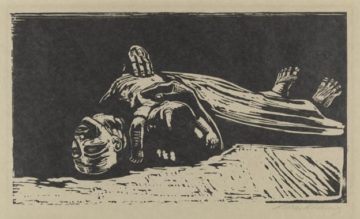

Being in Berkeley for more than four decades I have met and encountered many leftists and several of them are/were radical in their politics, though in recent years the radical fervor has been somewhat on the decline even in Berkeley. I remember some time back reading one east-coast journalist describing Berkeley, with a pinch of exaggeration, as moving from being the Left capital of the US to being its gourmet capital—this transition is, of course, most well-known in the case of Alice Waters who, a Berkeley activist in the 1960’s, started her iconic restaurant Chez Panisse in the next decade, though she herself considers the novel approach to food embodied in that restaurant—insistence on fresh ingredients and cooperative relations with local farmers– as growing out of the same counter-culture movement. (This transition was, of course, much more agreeable than some of the militant Black Panther leaders of 1960’s Oakland turning to Christian evangelism). Betroffenheitskitsch. It is not an easy word to say. That’s because it is German and Germans love to make compound words. The core of the word is the adjective betroffen, which means ‘affected’, but also ‘concerned’, and even ‘shocked’ or ‘stricken’. Betroffenheit is the noun and can be translated as ‘shock’, ‘consternation’, ‘concern’. Finally, we add the word kitsch, which makes the whole thing, well, kitschy. Betroffenheitskitsch is shock or deep concern that has been taken to the level of kitsch.

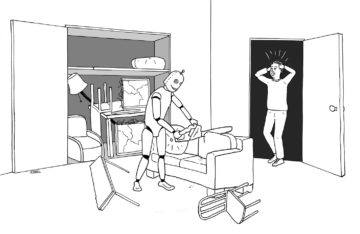

Betroffenheitskitsch. It is not an easy word to say. That’s because it is German and Germans love to make compound words. The core of the word is the adjective betroffen, which means ‘affected’, but also ‘concerned’, and even ‘shocked’ or ‘stricken’. Betroffenheit is the noun and can be translated as ‘shock’, ‘consternation’, ‘concern’. Finally, we add the word kitsch, which makes the whole thing, well, kitschy. Betroffenheitskitsch is shock or deep concern that has been taken to the level of kitsch. From a showmanship standpoint, Google’s new robot project

From a showmanship standpoint, Google’s new robot project  There is no human endeavor that does not have a theory of it — a set of ideas about what makes it work and how to do it well. Music is no exception, popular music included — there are reasons why certain keys, chord changes, and rhythmic structures have proven successful over the years. Nobody has done more to help people understand the theoretical underpinnings of popular music than today’s guest, Rick Beato. His YouTube videos dig into how songs work and what makes them great. We talk about music theory and how it contributes to our appreciation of all kinds of music.

There is no human endeavor that does not have a theory of it — a set of ideas about what makes it work and how to do it well. Music is no exception, popular music included — there are reasons why certain keys, chord changes, and rhythmic structures have proven successful over the years. Nobody has done more to help people understand the theoretical underpinnings of popular music than today’s guest, Rick Beato. His YouTube videos dig into how songs work and what makes them great. We talk about music theory and how it contributes to our appreciation of all kinds of music. However difficult it is to properly gauge the significance of historical events while still living through them, we can surely already state with confidence that the Covid pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine together constitute a truly seismic and transformative sequence of years for the world.

However difficult it is to properly gauge the significance of historical events while still living through them, we can surely already state with confidence that the Covid pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine together constitute a truly seismic and transformative sequence of years for the world. THE WRITER AND SCHOLAR

THE WRITER AND SCHOLAR The recipe for mammalian life is simple: take an egg, add sperm and wait. But two new papers demonstrate that there’s another way. Under the right conditions, stem cells can divide and self-organize into an embryo on their own. In studies published in Cell and Nature this month, two groups report that they have grown synthetic mouse embryos for longer than ever before. The embryos grew for 8.5 days, long enough for them to develop distinct organs — a beating heart, a gut tube and even neural folds.

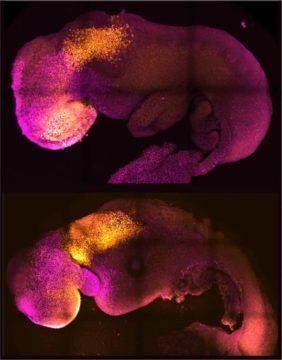

The recipe for mammalian life is simple: take an egg, add sperm and wait. But two new papers demonstrate that there’s another way. Under the right conditions, stem cells can divide and self-organize into an embryo on their own. In studies published in Cell and Nature this month, two groups report that they have grown synthetic mouse embryos for longer than ever before. The embryos grew for 8.5 days, long enough for them to develop distinct organs — a beating heart, a gut tube and even neural folds. Masha Gessen in The New Yorker (Photograph by Maxim Shemetov / Reuters):

Masha Gessen in The New Yorker (Photograph by Maxim Shemetov / Reuters): Fathimath Musthaq in Phenomenal World:

Fathimath Musthaq in Phenomenal World: