Month: April 2022

The Story Of A Stare Down

Penelope Rowlands at The American Scholar:

“It seems as though Cromwell has More right where he wants him,” the social scientist Todd Oakley writes in his essay, “Do Pictures Stare?” Many art-loving New Yorkers will immediately get the reference. At the Frick Collection on Fifth Avenue, two portraits by the German artist Hans Holbein the Younger—one of Sir Thomas More, the other of Thomas Cromwell—faced off against each other for years from either side of a majestic fireplace in the hallowed, oak-paneled room known as the Living Hall.

“It seems as though Cromwell has More right where he wants him,” the social scientist Todd Oakley writes in his essay, “Do Pictures Stare?” Many art-loving New Yorkers will immediately get the reference. At the Frick Collection on Fifth Avenue, two portraits by the German artist Hans Holbein the Younger—one of Sir Thomas More, the other of Thomas Cromwell—faced off against each other for years from either side of a majestic fireplace in the hallowed, oak-paneled room known as the Living Hall.

Other visitors to the Frick have doubtless shared Oakley’s impression. It’s fun to imagine that Cromwell glares at More, daggers drawn, at least telepathically. For his part, More—a study in tranquility—stares thoughtfully in Cromwell’s direction. He’s looking into the distance toward his left, at something we can’t see. His expression is pensive, calm, direct.

more here.

Exploring The Midwest’s Forgotten Utopian Communes

Evan Malmgren at The Baffler:

This story is fairly typical. Inland America is pocked with the unmarked graves of communitarian utopias—primitive socialist and communist experiments—that tried to rebuild the world on what was assumed to be virgin soil. Ephrata, Pennsylvania; Germantown, Tennessee; Utopia, Ohio; Brentwood, New York; Iowa’s Amana Colonies: these and many other towns were originally settled by communalists with lofty visions of abolishing private property, quashing material inequity, and transcending divisive individualism.

This story is fairly typical. Inland America is pocked with the unmarked graves of communitarian utopias—primitive socialist and communist experiments—that tried to rebuild the world on what was assumed to be virgin soil. Ephrata, Pennsylvania; Germantown, Tennessee; Utopia, Ohio; Brentwood, New York; Iowa’s Amana Colonies: these and many other towns were originally settled by communalists with lofty visions of abolishing private property, quashing material inequity, and transcending divisive individualism.

It makes sense that those seeking the fringe of a New World might be driven by powerful ideological convictions. But while European settlers dreamed of abolishing old hierarchies in the map’s blank spots, these blanks were always a fantasy. The allure of self-directed freedom in unsullied lands largely folded back into a vanguard of dispossession and genocide, with naïve radicals paving the way for the extension of the very structures they had hoped to escape.

more here.

Against “Realism” about the Russian Invasion of the Ukraine

by Tim Sommers

The New York Times’ columnist who thought that a good way to capture the interconnectedness of the modern world was to say that “The World is Flat” – an idea, arguably, better captured by saying that the world is round (which it is) – recently joined the chorus of pundits saying, yeah, Putin started the war in the Ukraine, but the U.S. is also to blame – or at least, “America is not entirely innocent of fueling [Putin’s] fires.”

Former Kremlin advisor Sergey Karaganov has been widely quoted (more quoted, than vetted, I think) as saying “For 25 years, people like myself have been saying that if NATO and Western alliance’s expand beyond certain red lines, especially into Ukraine, there will be a war. I envisioned that scenario as far back as 1997.” Envisioned, maybe, is not the right word. As an influential advisor to Putin, it seems he advised Putin that destroying the Ukraine was necessary to prevent NATO expansion. In an interesting turn of phrase Karaganov now says that what Russia “needs is a kind of solution which would be called peace.” Which would be called peace? Right. That doesn’t sound ominous, at all.

There are plenty of other examples of the argument that the West, the U.S., and/or NATO, share blame for the war for not making clear that they would never, ever going allow the Ukraine to join NATO – even if that would have been good for both parties (absent Russian aggression). What if anything is wrong with this style of argument? Scholars and theorists of foreign affairs call the view represented “realism”. Personally, I’m against it. Read more »

Should a scientist have faith?

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Scientists like to think that they are objective and unbiased, driven by hard facts and evidence-based inquiry. They are proud of saying that they only go wherever the evidence leads them. So it might come as a surprise to realize that not only are scientists as biased as non-scientists, but that they are often driven as much by belief as are non-scientists. In fact they are driven by more than belief: they are driven by faith. Science. Belief. Faith. Seeing these words in a sentence alone might make most scientists bristle and want to throw something at the wall or at the writer of this piece. Surely you aren’t painting us with the same brush that you might those who profess religious faith, they might say?

But there’s a method to the madness here. First consider what faith is typically defined as – it is belief in the absence of evidence. Now consider what science is in its purest form. It is a leap into the unknown, an extrapolation of what is into what can be. Breakthroughs in science by definition happen “on the edge” of the known. Now what sits on this edge? Not the kind of hard evidence that is so incontrovertible as to dispel any and all questions. On the edge of the known, the data is always wanting, the evidence always lacking, even if not absent. On the edge of the known you have wisps of signal in a sea of noise, tantalizing hints of what may be, with never enough statistical significance to nail down a theory or idea. At the very least, the transition from “no evidence” to “evidence” lies on a continuum. In the absence of good evidence, what does a scientist do? He or she believes. He or she has faith that things will work out. Some call it a sixth sense. Some call it intuition. But “faith” fits the bill equally.

If this reliance on faith seems like heresy, perhaps it’s reassuring to know that such heresies were committed by many of the greatest scientists of all time. All major discoveries, when they are made, at first rely on small pieces of data that are loosely held. A good example comes from the development of theories of atomic structure. Read more »

Monday Poem

Ménage à Trois

isn’t it a miracle that

three atoms have combined

in chemical love to become

the slippery substance of that which

both bears and wrecks ships,

of bays that breed and

shelter life —sustain it,

of that essential stuff of bodies,

of billows of mist that rain

and surge through taps,

of glaciers that have weighed

upon continents for millennia,

until now

?

Jim Culleny

4/13/22

Paris is Dead

by Ethan Seavey

Every hour of every day I hear the pulsating rush of le Periph and I am reminded that Paris is dead. My dorm is at the very bottom of Paris such that if the city were a ball I’d be the spot that hits the ground. I sit in my windowsill. I watch cars drive on the highway in an unending flow, like blood in veins, fish in streams, but they’re all metal idols of life. Life does not go this fast. Life stops to take a rest.

Every hour of every day I hear the pulsating rush of le Periph and I am reminded that Paris is dead. My dorm is at the very bottom of Paris such that if the city were a ball I’d be the spot that hits the ground. I sit in my windowsill. I watch cars drive on the highway in an unending flow, like blood in veins, fish in streams, but they’re all metal idols of life. Life does not go this fast. Life stops to take a rest.

It seems to me that Paris died forty years ago and is now taxidermic like the fawn I saw guarding an antique shop in the 9th arrondissement. Someone must have prepared the fawn’s body to be preserved, then sewn a tailored military uniform for its cartoonish appearance. Through the window it looks perfectly reanimated and proud to be enlisted in the French infantry. Up close it’s just dusty and reminds me that it has been dead for a long time.

Something stopped in Paris in the 1980s. I think it happened when Parisian food stopped developing. You love French food until you live in Paris and then you decide you can’t have another meal of meat, cheese, butter and bread. A waiter in a French café will serve you a brown omelette, ignore you until you’ve properly begged for the check, and proceed to charge you 14 euros. Paris is proud of its food. They won’t change it any time soon. Read more »

Perceptions

Sughra Raza. Color Burst, Costa Rica 2003.

Sughra Raza. Color Burst, Costa Rica 2003.

Analog photo, digitally edited.

Forgetting Aristotle

by Dwight Furrow

For many of the ancient philosophers that we still read today, philosophy was not only an intellectual pursuit but a way of life, a rigorous pursuit of wisdom that can guide us through the difficult decisions and battle for self-control that characterize a human life. That view of philosophy as a practical guide faded throughout much of modern history as the idea of a “way of life” was deemed a matter of personal preference and philosophical ethics became a study of how we justify right action. But with the recognition that philosophy might speak to broader concerns than those that get a hearing in academia, this idea of philosophy as a way of life has been revived in recent years.

For many of the ancient philosophers that we still read today, philosophy was not only an intellectual pursuit but a way of life, a rigorous pursuit of wisdom that can guide us through the difficult decisions and battle for self-control that characterize a human life. That view of philosophy as a practical guide faded throughout much of modern history as the idea of a “way of life” was deemed a matter of personal preference and philosophical ethics became a study of how we justify right action. But with the recognition that philosophy might speak to broader concerns than those that get a hearing in academia, this idea of philosophy as a way of life has been revived in recent years.

However, if philosophy is to be successfully conceptualized as a way of life, it will have to overcome that legacy of modern moral philosophy which has little to say about life as lived. You can sift through the works of Hume, Kant, Mill, and their heirs without discovering much that is practically useful. Of all the mainstream views in ethics, one has to return to the ancient philosophers, most notably Aristotle, and their modern interpreters to find discussions of the nature of human flourishing, practical wisdom, and the qualities of character required to achieve it. But alas, it seems to me, even that return to Aristotle is not sufficient to make the argument for philosophy as a way of life. Despite Aristotle’s laudable sensitivity to practical concerns, his work is afflicted with idealizations that limit its value for everyday moral reflection. Read more »

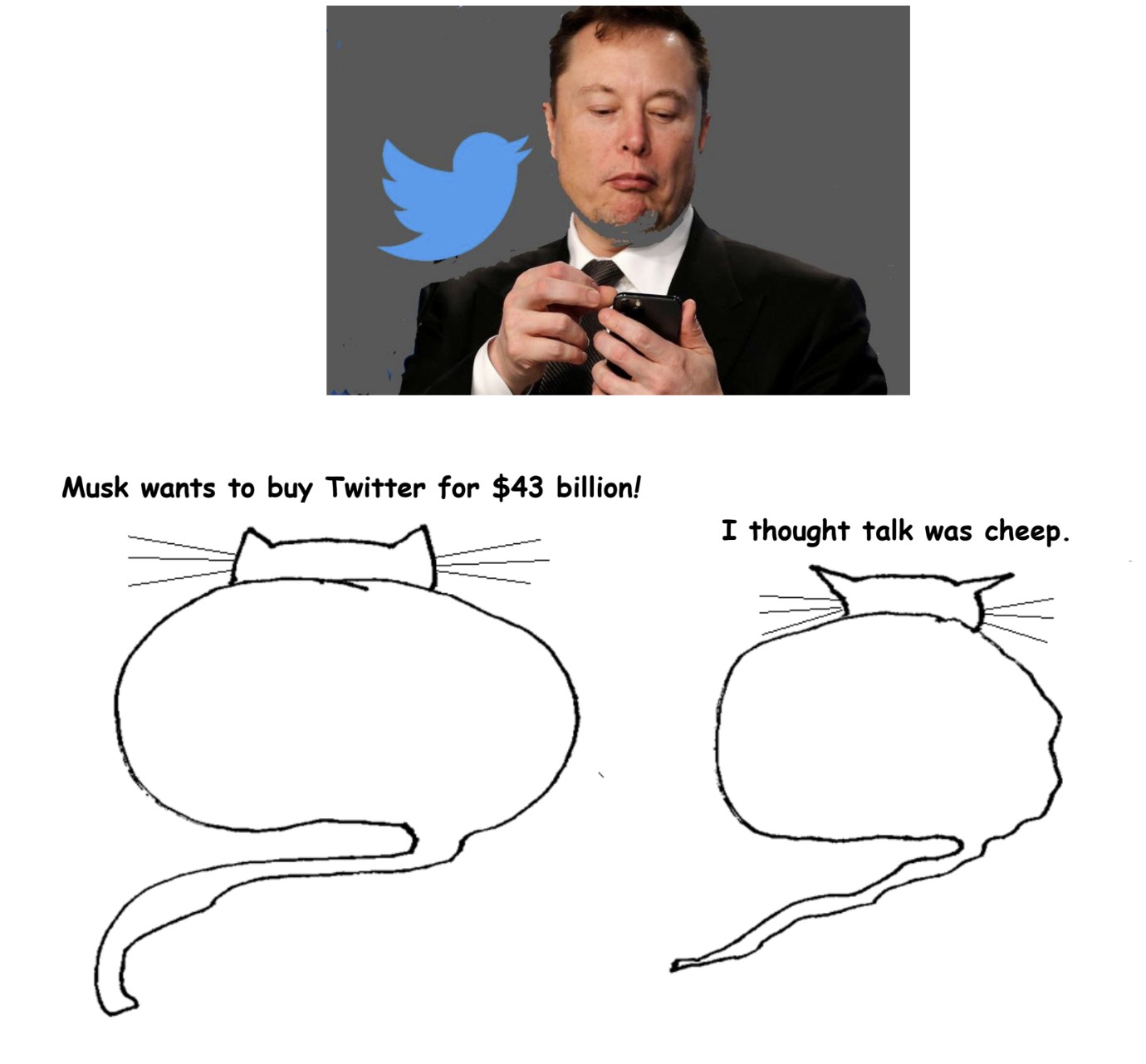

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

‘What-aboutism’ and the Universal

by Chris Horner

Two Scenarios

First scenario: you attempt to criticise, condemn or otherwise focus on an unjust regime, act of aggression, atrocity, or cruelty. An example: a school has been bombed and children have died. It is a war crime and you name it as such as an evil, criminal thing. Soon after the words leave your mouth, or get posted online, someone responds with something along these lines: yes, that’s all very well, but why just condemn that? What about..? They then name some other, maybe similar atrocity that you haven’t mentioned. The case you wanted to draw attention to is lost, displaced and deferred to other examples that your interlocutor claims you should be equally concerned about. This is what aboutism, and it can be quite annoying.

Second Scenario: someone criticises, condemns or otherwise focuses on an unjust regime, act of aggression, atrocity, cruelty. Let’s say a school has been bombed and children have died. It is a war crime and they name it as such, as an evil, criminal thing. But it is quite obvious to you that they are being selective in their outrage: they don’t seem to care about the times schools have been bombed in other places, by other militaries. Why just this example? So you point this out. All children matter, and not just the ones your interlocutor seems to care about. This is selective outrage, and it can be quite annoying, to put it mildly.

Clearly, one can find oneself on either side of this kind of exchange. One person’s demand for ethical or political consistency can be just a case of what aboutism to another. So is it just the effect of where one is positioned in an argument? Perhaps, but it would be useful to know how to think things through in such a way as to avoid both selective outrage (where only X seems to matter, but not similar cases Y or Z), and mere ‘what aboutism’, which demands an interest in not only case X but in all the other cases that could be considered – an infinite demand that can never be met. Read more »

Monday Photo

Varieties of Churchgoing in Ladd’s Addition: Part I

by David Oates

Full of good cheer – when does walking not perk me up? – on a too-cool March morning, past houses nicer than mine by several hundred grand with wide verandahs and Craftsman gables, and through a deep urban forest of elms, I make my way towards church.

Church!

Not exactly my normal behavior – not for lo these many decades since achieving my apostasy, my ex-Baptist-ness, and then at length making peace with it. I carried no axe to grind. Though I walked right past a low-slung building with a sign reading – no kidding! – “Chinese Baptist Church.”

I’ll return to that. But today my destination is yet more exotic, you could say, though just one more block away. “St. Sharbel Catholic Church, Maronite Rite” it proclaims itself. Whatever that might mean. My mission was to find out by attending the eleven-o’clock service.

This neighborhood, which I live right next to though not quite in – seems oddly attractive to churches. One of the oldest planned developments in the western US, called “Ladd’s Addition” after its 1891 developer, former mayor William S. Ladd, it forms a square just a half-mile on a side, yet is studded with temples and houses of worship, sanctuaries grand or cozy, surprising or predictable . . . so many varieties of religious belief, so many flavors and even hues. Even in ethnically-challenged Portland.

To what end? Serving what need or what god (or gods)? Who can say. Answer: Me. Or I can try, anyway. Read more »

Charaiveti: Journey From India To The Two Cambridges And Berkeley And Beyond, Part 40

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Andreu Mas-Collel, a mathematical economist from Catalonia, came to Berkeley before I did. He was a student activist in Barcelona, was expelled from his University for activism (those were the days of Franco’s Spain), and later finished his undergraduate degree in a different university, in north-west Spain. When I met him in Berkeley he was already a high-powered theorist using differential topology in general-equilibrium analysis, in ways that were far beyond my limited technical range in economic theory. But when we met, it was our shared interest in history, politics, and culture that immediately made us good friends, and his warm cheerful personality was an added attraction for me. (His wife, Esther, a mathematician from Chile, was as decent a person as she was politically alert).

Andreu Mas-Collel, a mathematical economist from Catalonia, came to Berkeley before I did. He was a student activist in Barcelona, was expelled from his University for activism (those were the days of Franco’s Spain), and later finished his undergraduate degree in a different university, in north-west Spain. When I met him in Berkeley he was already a high-powered theorist using differential topology in general-equilibrium analysis, in ways that were far beyond my limited technical range in economic theory. But when we met, it was our shared interest in history, politics, and culture that immediately made us good friends, and his warm cheerful personality was an added attraction for me. (His wife, Esther, a mathematician from Chile, was as decent a person as she was politically alert).

A few times it so happened that when I went to see some obscure Latin American film in a special showing at a remote movie hall in Berkeley, at the end when the lights came up, I discovered that Andreu was also in the audience, and then we sat down somewhere to discuss the film animatedly. We used to frequently visit each other’s home. One time Romila Thapar, the eminent historian of ancient India, came to visit us from Delhi, and we asked Andreu and Esther to join us. Later he told others about meeting ‘this very impressive woman’ at our place.

When, after a few years, he left Berkeley, first for Harvard, and then in 1990’s back to Barcelona, I sorely missed him. At Harvard Andreu co-authored what is probably the most used graduate textbook in microeconomic theory in the world. In Barcelona he was a Professor at the Pompeu Fabra University. He later joined politics, serving the Catalonian government in different capacities, including as the Minister of Economy and Knowledge in 2010-16. In 2021 he was slapped with a multi-million-euro penalty by the Spanish Court of Auditors for allegedly participating as Minister in activities that led to the abortive Catalonian bid for independence; I believe the case is still pending. Read more »

An Interview with Parul Sehgal

Zachary Fine in The Oxonian Review:

Part of the pleasure of reading Parul Sehgal’s book reviews when she served as a critic for The New York Times was the impression that her prose had slipped past the censors. Some of her sentences had the crispness of newspaper copy but others were much more blurred and atmospheric. You could watch her trialing an idea, circling it with adjectives, letting it rise with the sound of the words.

Part of the pleasure of reading Parul Sehgal’s book reviews when she served as a critic for The New York Times was the impression that her prose had slipped past the censors. Some of her sentences had the crispness of newspaper copy but others were much more blurred and atmospheric. You could watch her trialing an idea, circling it with adjectives, letting it rise with the sound of the words.

Here I sit, having just completed a novel that lines up these pieties and threatens to dispatch them with calm and ruthless efficiency . . . it is most thoroughly and exuberantly about the hunched, clammy, lightly paranoid, entirely demented feeling of being ‘very online’—the relentlessness of performance required, the abdication of all inwardness, subtlety and good sense.

This in The New York Times? And not an anomaly but every week, give or take, for four years. Her pieces were elliptical, slightly wry, unafraid to double back on themselves. One could sense that she was thrilling to the limits of the form and not simply meeting a deadline. ‘Book reviewing’, she said, ‘can get a bad rap as glorified book reports, when it really is this amazing instrument, this vocabulary of pleasure.’

More here.

Life With Longer Genetic Codes Seems Possible — but Less Likely

Yasemin Saplakoglu in Quanta:

As wildly diverse as life on Earth is — whether it’s a jaguar hunting down a deer in the Amazon, an orchid vine spiraling around a tree in Congo, primitive cells growing in boiling hot springs in Canada, or a stockbroker sipping coffee on Wall Street — at the genetic level, it all plays by the same rules. Four chemical letters, or nucleotide bases, spell out 64 three-letter “words” called codons, each of which stands for one of 20 amino acids. When amino acids are strung together in keeping with these encoded instructions, they form the proteins characteristic of each species. With only a few obscure exceptions, all genomes encode information identically.

As wildly diverse as life on Earth is — whether it’s a jaguar hunting down a deer in the Amazon, an orchid vine spiraling around a tree in Congo, primitive cells growing in boiling hot springs in Canada, or a stockbroker sipping coffee on Wall Street — at the genetic level, it all plays by the same rules. Four chemical letters, or nucleotide bases, spell out 64 three-letter “words” called codons, each of which stands for one of 20 amino acids. When amino acids are strung together in keeping with these encoded instructions, they form the proteins characteristic of each species. With only a few obscure exceptions, all genomes encode information identically.

Yet, in a new study published last month in eLife, a group of researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Yale University showed that it’s possible to tweak one of these time-honored rules and create a more expansive, entirely new genetic code built around longer codon words.

More here.

There’s More to Authoritarianism Than Cults of Personality

Krithika Varagur in The New Republic:

It’s remarkable: For more than a year, it’s been impossible to describe any world leader as a version of the sitting U.S. president. Run this thought experiment yourself: Who might be the “Joe Biden of South America”? Or “Central Europe’s Biden”? You draw a blank. What a contrast from the four years in which the world contained Hungary’s Trump, Brazil’s Trump, India’s Trump, Turkey’s Trump, the Philippines’ Trump, and so many more. The parallels between these leaders and Trump were chilling, but they were also a boon for the geopolitical commentariat: the sundry experts, analysts, specialists, and columnists who used them to give an intelligible shape to troubling developments in places far from the United States. The stakes were uncontestably high, and the conditions for analogy, the Swiss Army knife of such professions, had never been so ripe.

It’s remarkable: For more than a year, it’s been impossible to describe any world leader as a version of the sitting U.S. president. Run this thought experiment yourself: Who might be the “Joe Biden of South America”? Or “Central Europe’s Biden”? You draw a blank. What a contrast from the four years in which the world contained Hungary’s Trump, Brazil’s Trump, India’s Trump, Turkey’s Trump, the Philippines’ Trump, and so many more. The parallels between these leaders and Trump were chilling, but they were also a boon for the geopolitical commentariat: the sundry experts, analysts, specialists, and columnists who used them to give an intelligible shape to troubling developments in places far from the United States. The stakes were uncontestably high, and the conditions for analogy, the Swiss Army knife of such professions, had never been so ripe.

The Age of the Strongman: How the Cult of the Leader Threatens Democracy Around the World by Gideon Rachman, chief foreign affairs columnist for the Financial Times, is one of several new books that attempt to explain today’s authoritarians as a single phenomenon by slotting their rise and their “playbooks”—a favorite term of these analyses—into a unifying framework.

More here.

Mankind can solve all problems, argues British physicist David Deutsch

Rafaela von Bredow and Johann Grolle in Der Speigel:

DER SPIEGEL: Professor Deutsch, you believe that mankind, after billions and billions of years of absolute monotony in the universe, will now reshape it to their liking, that a new cosmological era is coming. Are you serious?

Deutsch: I am not the first to propose this idea. The Italian geologist Antonio Stoppani wrote in the 19th century that he had no hesitation in declaring man to be a new power in the universe, equivalent to the power of gravitation.

Deutsch: I am not the first to propose this idea. The Italian geologist Antonio Stoppani wrote in the 19th century that he had no hesitation in declaring man to be a new power in the universe, equivalent to the power of gravitation.

DER SPIEGEL: And fly to distant planets? Tap energy from black holes? Conquer entire galaxies?

Deutsch: I am not saying that we will necessarily do all this. I am only saying that, in principle, there is nothing to stop us. Only the laws of physics could prevent us. And we do not know a law of physics that forbids us, for example, from traveling to distant stars.

More here.

How Homeownership Changes You

Joe Pinsker in The Atlantic:

Growing up, Erin Nelson used to make fun of their dad for spending so much time looking out the window at what the neighbors were up to. “Now I’m that person,” Nelson, a 31-year-old who bought their first house a year ago in Portland, Oregon, told me. “I’m always peeking out the window … That’s like my new TV.” Nelson, who uses they/them pronouns, has realized that as a homeowner, their life is bound up with the people next door in a way it never has been before.

Growing up, Erin Nelson used to make fun of their dad for spending so much time looking out the window at what the neighbors were up to. “Now I’m that person,” Nelson, a 31-year-old who bought their first house a year ago in Portland, Oregon, told me. “I’m always peeking out the window … That’s like my new TV.” Nelson, who uses they/them pronouns, has realized that as a homeowner, their life is bound up with the people next door in a way it never has been before.

Buying a first house is, for those who can afford it, among the largest financial decisions someone makes in their life, and lately, the process has only gotten more stressful: During the pandemic, home prices have shot up, and shopping for a house has become intimidatingly competitive in many places. But even some winners of the competition have buyer’s remorse. In a recent survey from the real-estate site Zillow, roughly one-third of respondents reported regretting how much work or maintenance their home required, and roughly one-fifth concluded that they had paid too much.

Perhaps forgotten amid the bidding wars and the rush to lock in a mortgage as interest rates rise is the fact that this transaction has a way of changing people as well. In addition to buying an assemblage of wood, glass, and other materials and committing to a host of unfamiliar chores, homeowners are also buying a psychological grab bag of new stressors, time sucks, comforts, perks, and trivial fixations—such as the neighbors’ comings and goings. Homeownership can change your mental time horizon, your conception of your community, and your stakes in a physical place.

More here.

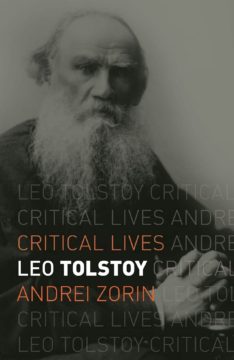

A Genius on the Wrong Side of History: Tolstoy’s Conflicts and Contradictions

Maria Rubin in The NY Review of Books:

IT IS DAUNTING to write a biography of Tolstoy. Hundreds or even thousands of books have already put each detail of his life and work under a microscope, and the archives contain no more hidden treasures. Yet, new interpretations of Tolstoy’s life continue to pour in, with more expected in the run-up to the writer’s 200th birthday in 2028. One of the most immediately obvious advantages of Andrei Zorin’s Leo Tolstoy is its brevity. And I don’t mean this as a backhanded compliment. While other biographies tend to compete with the author’s greatest novels in length, this medium-format book of roughly 200 pages will be welcomed by those who want to learn more about the legendary Russian writer without a major time commitment.

IT IS DAUNTING to write a biography of Tolstoy. Hundreds or even thousands of books have already put each detail of his life and work under a microscope, and the archives contain no more hidden treasures. Yet, new interpretations of Tolstoy’s life continue to pour in, with more expected in the run-up to the writer’s 200th birthday in 2028. One of the most immediately obvious advantages of Andrei Zorin’s Leo Tolstoy is its brevity. And I don’t mean this as a backhanded compliment. While other biographies tend to compete with the author’s greatest novels in length, this medium-format book of roughly 200 pages will be welcomed by those who want to learn more about the legendary Russian writer without a major time commitment.

Zorin’s book achieves the ultimate expectation set by the biography genre — he creates a consistent representation of Tolstoy’s integral personality. To begin with, he does not revisit the familiar dichotomy of Tolstoy the artist versus Tolstoy the thinker. According to this narrative, the writer turned to excessive moralizing after completing War and Peace and Anna Karenina, gradually suffocating his artistic genius. In the colorful words of Tatyana Tolstaya, the writer’s distant descendent and a popular author in her own right, once he turned to preaching the “quill fell out of his hand.” Tolstoy himself was very much aware of this inner conflict and in later life “resolved” it by condemning much of European art and literature, his own fiction included. Whereas many scholars have been all too eager to assimilate this binary paradigm, Zorin writes his biography against that trend. He presents Tolstoy as a sum total of all of his various activities — fiction, nonfiction, correspondence, oral teachings, religious writings, direct action, and even family squabbles — seamlessly integrated into the text of his life. While Tolstoy’s path seems full of unexpected shifts from one extreme to the other (from a dissolute lifestyle to near-chastity, from hunting to vegetarianism, from fiction to preaching, from luxury to asceticism), Zorin’s book shows that every juncture was just another manifestation of the inner logic of his existence. In this light, the spiritual crisis of 1878, when Tolstoy appeared to have rejected nearly all of his former values, was nothing sudden: this “conversion” became a culmination of a lifelong quest for the meaning of life and death, deep self-reflection and religious skepticism.

More here.