by R. Passov

After Steve Jobs hit his VP of development on the forehead, called him a stupid fuck, then stormed out of a meeting that had been set up to see George’s invention, everything changed.

The invention, George said, was on the motherboard. Dell and HP were buying 40 million so that no matter where you were in the world you could grab the local, over-the-air broadcast signal and with a little software, read the signal by the hardware, turning your computer into a TV.

By 2005, Jobs didn’t want anyone reaching out over the air. He wanted everyone to come through the Apple store. Apparently, neither his VP of development or George knew that. On its way toward bankruptcy, CrestaTech ate a fortune.

* * *

Back in the early 1990’s, before one of Sun Microsystems frequent purges forced me out, I shared an office with George and a fellow named Hung Gee. I came to understand something of what George labored on; learning the arc of his career from Daisy Systems – an innovator in microchip design tools – through to Sun where he managed a small corner of the Scalable Processor Architecture or SPARC Chip. As the geometry of microprocessors shrank, electrons traveled shorter distances. The non-intuitive result was to ask less of the hardware (the microprocessor) and more of the software.

Hung Gee was harder to pierce. George believes he can trace Hong Gee’s path to the parking lot of MIPS, another architectural innovator, and to the day in that parking lot when a man with the same name as Hong Gee shot his boss.

Gérard Roland came to Berkeley only around the turn of this century. He grew up in Belgium, was a radical student, and after the student movements of Europe subsided, he supported himself for a time by operating trams in the city. When he was wooing his girlfriend (later wife), Heddy, she used to get a free ride in his trams. (A few years back when I visited them one summer in their villa in the Italian countryside near Lucca, Heddy told me in jest that those days she was content with a free tram ride, but now she needed a house in Tuscany to be placated). Gérard is also a good cook.

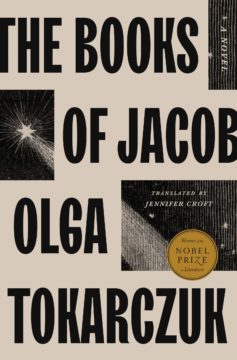

Gérard Roland came to Berkeley only around the turn of this century. He grew up in Belgium, was a radical student, and after the student movements of Europe subsided, he supported himself for a time by operating trams in the city. When he was wooing his girlfriend (later wife), Heddy, she used to get a free ride in his trams. (A few years back when I visited them one summer in their villa in the Italian countryside near Lucca, Heddy told me in jest that those days she was content with a free tram ride, but now she needed a house in Tuscany to be placated). Gérard is also a good cook. The Seattle Times chatted with Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk about her immersive, visionary 1,000-page novel that follows the extraordinary life of Jacob Frank, a Polish Jew who believed himself to be the Messiah and commanded a large religious movement in the 18th century.

The Seattle Times chatted with Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk about her immersive, visionary 1,000-page novel that follows the extraordinary life of Jacob Frank, a Polish Jew who believed himself to be the Messiah and commanded a large religious movement in the 18th century. On April 4,

On April 4, I think we’re laboring under a moment in which many believe that the sole function of art is to provide moral guidance.

I think we’re laboring under a moment in which many believe that the sole function of art is to provide moral guidance.

Wet earth. Loam. Bitter ash, brine on the wind. The unfurling of cedar, a smell that takes me out of this place and back to bathtubs in Japan; a portal of a scent, sacred and red. These are the smells of the Pacific Northwest wood from where I write this. In the daytime, as light pours around the unfamiliar landscape, I think of it as a new smell, something to gulp. But last night, clambering up the half-hill toward the cottage where I am staying, I took another breath and was suddenly tearful. The damp soil transformed into the smell of my Jiji, wood-smoke mimicking cigarette-smoke lingering in the folds of his shirt.

Wet earth. Loam. Bitter ash, brine on the wind. The unfurling of cedar, a smell that takes me out of this place and back to bathtubs in Japan; a portal of a scent, sacred and red. These are the smells of the Pacific Northwest wood from where I write this. In the daytime, as light pours around the unfamiliar landscape, I think of it as a new smell, something to gulp. But last night, clambering up the half-hill toward the cottage where I am staying, I took another breath and was suddenly tearful. The damp soil transformed into the smell of my Jiji, wood-smoke mimicking cigarette-smoke lingering in the folds of his shirt. “We often begin to understand things only after they break down. This is why, in addition to being a worldwide catastrophe, the pandemic has been a large-scale philosophical experiment,” Jonathan Malesic, author of The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives,

“We often begin to understand things only after they break down. This is why, in addition to being a worldwide catastrophe, the pandemic has been a large-scale philosophical experiment,” Jonathan Malesic, author of The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives,  Robin D. G. Kelley in Boston Review:

Robin D. G. Kelley in Boston Review: James McAuley in The New Yorker (Photograph by Rit Heize / Xinhua / Getty):

James McAuley in The New Yorker (Photograph by Rit Heize / Xinhua / Getty): Alex Yablon , Nicholas Mulder, Javier Blas in Phenomenal World:

Alex Yablon , Nicholas Mulder, Javier Blas in Phenomenal World: In “Indelible City,” Louisa Lim charts how her own identity as a Hong Konger had never been so clear until China’s brutal attempts to crush pro-democracy protests in 2019. She had been feeling increasingly alienated from a densely populated place where extreme inequality, soaring costs and shrinking real estate made “the very act of living” — even for “still very privileged” people like her — completely exhausting. Lim’s experience as a reporter amid a swell of protesters changed that. She could feel her face flush and her throat well up — not from the tear gas, of which there was plenty, but from a surge of emotions: “I’d fallen in love with Hong Kong all over again.”

In “Indelible City,” Louisa Lim charts how her own identity as a Hong Konger had never been so clear until China’s brutal attempts to crush pro-democracy protests in 2019. She had been feeling increasingly alienated from a densely populated place where extreme inequality, soaring costs and shrinking real estate made “the very act of living” — even for “still very privileged” people like her — completely exhausting. Lim’s experience as a reporter amid a swell of protesters changed that. She could feel her face flush and her throat well up — not from the tear gas, of which there was plenty, but from a surge of emotions: “I’d fallen in love with Hong Kong all over again.” JS: What do you see as the differences between academic writing and other forms of writing?

JS: What do you see as the differences between academic writing and other forms of writing?