by Eric J. Weiner

In a recent article in The Atlantic, Shadi Hamid, contributing writer and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, states reproachfully that “Donald Trump’s election (in 2016) led to a whole cottage industry of thinking that fascism is near, right here at home.” For many scholars and writers in this proverbial “cottage industry,” Joe Biden’s victory will do little to change their minds regarding what they see as the growing threat of fascism in the United States. For Hamid, this is a mistake with serious implications. He is concerned that people who reference fascism to describe what is happening in the United States, either as a warning of the unforeseen terror to come or as an analysis of what is already happening, are confused about what fascism actually is. To highlight the dangers of relativistic thinking in regards to fascism, he quotes George Orwell who wrote, “I have heard it applied to farmers, shopkeepers, Social Credit, corporal punishment, fox-hunting, bull-fighting, the 1922 Committee, the 1941 Committee, Kipling, Gandhi, Chiang Kai-Shek, homosexuality, Priestley’s broadcasts, Youth Hostels, astrology, women, dogs and I do not know what else.” Orwell’s point and Hamid’s fear is that when words/concepts become relative—when signifier and signified float willy-nilly along the shifting winds of power and ideology—they risk undermining the critical capacities of language. More specifically, Hamid argues that the relativity of the term is causing these scholars and commentators to ignore examples of “real” fascism when they occur. The consequence of this ignorance, he argues, negatively impacts the people who are struggling to survive fascist violence throughout the world. Hamid writes,

In a recent article in The Atlantic, Shadi Hamid, contributing writer and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, states reproachfully that “Donald Trump’s election (in 2016) led to a whole cottage industry of thinking that fascism is near, right here at home.” For many scholars and writers in this proverbial “cottage industry,” Joe Biden’s victory will do little to change their minds regarding what they see as the growing threat of fascism in the United States. For Hamid, this is a mistake with serious implications. He is concerned that people who reference fascism to describe what is happening in the United States, either as a warning of the unforeseen terror to come or as an analysis of what is already happening, are confused about what fascism actually is. To highlight the dangers of relativistic thinking in regards to fascism, he quotes George Orwell who wrote, “I have heard it applied to farmers, shopkeepers, Social Credit, corporal punishment, fox-hunting, bull-fighting, the 1922 Committee, the 1941 Committee, Kipling, Gandhi, Chiang Kai-Shek, homosexuality, Priestley’s broadcasts, Youth Hostels, astrology, women, dogs and I do not know what else.” Orwell’s point and Hamid’s fear is that when words/concepts become relative—when signifier and signified float willy-nilly along the shifting winds of power and ideology—they risk undermining the critical capacities of language. More specifically, Hamid argues that the relativity of the term is causing these scholars and commentators to ignore examples of “real” fascism when they occur. The consequence of this ignorance, he argues, negatively impacts the people who are struggling to survive fascist violence throughout the world. Hamid writes,

Words matter because they help order our understanding of politics both at home and abroad. If [Senator Tom] Cotton is a fascist, then we don’t know what fascism is. And if we don’t know what fascism is, then we will struggle to identify it when it threatens millions of lives—which is precisely what is happening today in areas under Beijing’s control. Chinese authorities have tightened their grip on Hong Kong. And while the world watches, they are undertaking one of the most terrifying campaigns of ethnic cleansing and cultural genocide since World War II in Xinjiang province, with more than 1 million Muslim Uighurs in internment camps, as well as reports of forced sterilization and mass rape.

In the face of Hamid’s concerns, and in the wake of Joe Biden’s victory, what should we make of the scholarship and academic journalism that resurrects and reconstructs the concept of fascism to explain what is currently happening in the United States or to warn people about what is politically probable if the Nation doesn’t radically change course? Read more »

Three is the second of the four brilliant and enigma-ridden novels that Ann Quin published before drowning off the coast of Brighton in 1973 at the age of thirty-seven. The mysterious character S—the absent protagonist or antiheroine hypotenuse of this love-triangle tale—dies in similar fashion … or perhaps she’s stabbed to death by a gang of nameless, faceless men before her body washes up onshore … or perhaps the stabbed dead body that washes up onshore is someone else… It’s difficult to tell. And the telling is difficult, too. And I would submit that it’s precisely these difficulties that make this gory story normal.

Three is the second of the four brilliant and enigma-ridden novels that Ann Quin published before drowning off the coast of Brighton in 1973 at the age of thirty-seven. The mysterious character S—the absent protagonist or antiheroine hypotenuse of this love-triangle tale—dies in similar fashion … or perhaps she’s stabbed to death by a gang of nameless, faceless men before her body washes up onshore … or perhaps the stabbed dead body that washes up onshore is someone else… It’s difficult to tell. And the telling is difficult, too. And I would submit that it’s precisely these difficulties that make this gory story normal.

In a recent article in

In a recent article in  High in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta of northern Colombia, the Kogi people peaceably live and farm. Having isolated themselves in nearly inaccessible mountain hamlets for five hundred years, the Kogi retain the dubious distinction of being the only intact, pre-Columbian civilization in South America. As such, they are also rare representatives of a sustainable farming way of life that persists until the modern era. Yet, more than four decades ago, even they noticed that their highland climate was changing. The trees and grasses that grew around their mountain redoubt, the numbers and kinds of animals they saw, the sizes of lakes and glaciers, the flows of rivers—everything was changing. The Kogi, who refer to themselves as Elder Brother and understand themselves to be custodians of our planet, felt they must warn the world. So in the late 1980s, they sent an emissary to contact the documentary filmmaker, Alan Ereira of the BBC—one of the few people they’d previously met from the outside world. In the resulting film,

High in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta of northern Colombia, the Kogi people peaceably live and farm. Having isolated themselves in nearly inaccessible mountain hamlets for five hundred years, the Kogi retain the dubious distinction of being the only intact, pre-Columbian civilization in South America. As such, they are also rare representatives of a sustainable farming way of life that persists until the modern era. Yet, more than four decades ago, even they noticed that their highland climate was changing. The trees and grasses that grew around their mountain redoubt, the numbers and kinds of animals they saw, the sizes of lakes and glaciers, the flows of rivers—everything was changing. The Kogi, who refer to themselves as Elder Brother and understand themselves to be custodians of our planet, felt they must warn the world. So in the late 1980s, they sent an emissary to contact the documentary filmmaker, Alan Ereira of the BBC—one of the few people they’d previously met from the outside world. In the resulting film,

People are basically good.

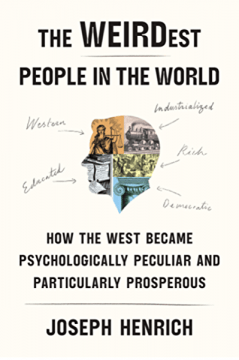

People are basically good. Here’s an interesting game. You receive 20 dollars, and you and three others can anonymously contribute any portion of this amount to a public pool. The amount of money in this pool is then multiplied by 1.5 and divided equally among all players. Repeat 10 times, then go home with your money. What will happen? How much would you contribute in round one, if you knew nothing about your fellow players?

Here’s an interesting game. You receive 20 dollars, and you and three others can anonymously contribute any portion of this amount to a public pool. The amount of money in this pool is then multiplied by 1.5 and divided equally among all players. Repeat 10 times, then go home with your money. What will happen? How much would you contribute in round one, if you knew nothing about your fellow players?

Now that a deranged president’s toxic presence will finally—finally!—begin to occupy increasingly smaller tracts of our inner lives, these new days might offer an ideal occasion to celebrate songs that sing of the singular mental spaces hidden inside us all—songs that can help re-acquaint us with ourselves.

Now that a deranged president’s toxic presence will finally—finally!—begin to occupy increasingly smaller tracts of our inner lives, these new days might offer an ideal occasion to celebrate songs that sing of the singular mental spaces hidden inside us all—songs that can help re-acquaint us with ourselves.

Put a small child in a room with a single marshmallow. Tell him that, if he can wait for five minutes, he gets a second one. Leave the room, and see what he does. Can he sit there, staring at that scrumptious-if-a-tad-rubbery mound of goo and powdered sugar and just fight off the urge to grab it, tear it to bits, and, like the Cheshire Cat, leave nothing but a smile?

Put a small child in a room with a single marshmallow. Tell him that, if he can wait for five minutes, he gets a second one. Leave the room, and see what he does. Can he sit there, staring at that scrumptious-if-a-tad-rubbery mound of goo and powdered sugar and just fight off the urge to grab it, tear it to bits, and, like the Cheshire Cat, leave nothing but a smile? When we are done rhyming words of hope and history to audacity we will need to wake up. When the much needed elation and good cheer wears off, of getting job one done, defeating Trump then the reality will set in.

When we are done rhyming words of hope and history to audacity we will need to wake up. When the much needed elation and good cheer wears off, of getting job one done, defeating Trump then the reality will set in. think about that. Though others may have one, I lack an analytic framework. The best I can do is to offer some things I’ve been thinking about.

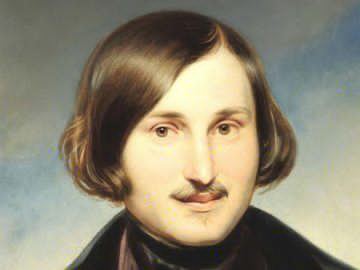

think about that. Though others may have one, I lack an analytic framework. The best I can do is to offer some things I’ve been thinking about. Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852), Russia’s greatest comic writer, thoroughly baffled his contemporaries. Strange, peculiar, wacky, weird, bizarre, and other words indicating enigmatic oddity recur in descriptions of him. “What an intelligent, queer, and sick creature!” remarked Turgenev; another major prose writer, Sergey Aksakov, referred to the “unintelligible strangeness of his spirit.” When Gogol died, the poet Pyotr Vyazemsky sighed, “Your life was an enigma, so is today your death.”

Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852), Russia’s greatest comic writer, thoroughly baffled his contemporaries. Strange, peculiar, wacky, weird, bizarre, and other words indicating enigmatic oddity recur in descriptions of him. “What an intelligent, queer, and sick creature!” remarked Turgenev; another major prose writer, Sergey Aksakov, referred to the “unintelligible strangeness of his spirit.” When Gogol died, the poet Pyotr Vyazemsky sighed, “Your life was an enigma, so is today your death.” Five years had passed since Czar Alexander II promised the emancipation of the serfs. Trusting in a map drawn on bark with the point of a knife by a Tungus hunter, three Russian scientists set out to explore an area of trackless mountain wilderness stretching across eastern Siberia. Their mission was to find a direct passage between the gold mines of the river Lena and Transbaikalia. Their discoveries would transform understanding of the geography of northern Asia, opening up the route eventually followed by the Trans-Manchurian Railway. For one explorer, now better known as an anarchist than a scientist, this expedition was also the start of a long journey towards a new articulation of evolution and the strongest possible argument for a social revolution.

Five years had passed since Czar Alexander II promised the emancipation of the serfs. Trusting in a map drawn on bark with the point of a knife by a Tungus hunter, three Russian scientists set out to explore an area of trackless mountain wilderness stretching across eastern Siberia. Their mission was to find a direct passage between the gold mines of the river Lena and Transbaikalia. Their discoveries would transform understanding of the geography of northern Asia, opening up the route eventually followed by the Trans-Manchurian Railway. For one explorer, now better known as an anarchist than a scientist, this expedition was also the start of a long journey towards a new articulation of evolution and the strongest possible argument for a social revolution. Dear Dan,

Dear Dan,