Christian Lorentzen in Bookforum:

“SENESCENCE” ISN’T QUITE THE RIGHT WORD for the stage the writers of the Baby Boom have reached. Sure, they may be collecting social security, the eldest of them in their mid-seventies, but the wonders of modern science may allow some another couple of decades of productivity. When the Reaper starts to come for the writer’s instrument, the first thing to go is flow, but that may not matter: fragments are in. In a decade or so, robbed of their transitions and reduced to accumulating prose shards, the octogenarian Boomers may find themselves newly trendy. A strange fate for a generation that entered the literary world at the height of its postmodern excesses: everyone still standing will turn into Lydia Davis.

“SENESCENCE” ISN’T QUITE THE RIGHT WORD for the stage the writers of the Baby Boom have reached. Sure, they may be collecting social security, the eldest of them in their mid-seventies, but the wonders of modern science may allow some another couple of decades of productivity. When the Reaper starts to come for the writer’s instrument, the first thing to go is flow, but that may not matter: fragments are in. In a decade or so, robbed of their transitions and reduced to accumulating prose shards, the octogenarian Boomers may find themselves newly trendy. A strange fate for a generation that entered the literary world at the height of its postmodern excesses: everyone still standing will turn into Lydia Davis.

Topical relevance is another matter. On these shores, the Dirty Realists have been the victims of their generational good fortune. The decades of affluence—and cushy teaching positions—that followed their breakout work have alienated them from the hardscrabble subject matter that made them so interesting in the first place. In Britain, the Boomers have been, since their arrival, the most celebrated literary cohort in history. Endless scandals, enormous book deals, a worldwide fatwa—one of them reviewing another without sufficient deference used to be the cause of international headlines. Arriving in a mature and thriving literary culture, many of them took up staff positions at venerable London papers—the Times Literary Supplement, the New Statesman, the Sunday Times, The Observer—and published in the upstart journals: Ian Hamilton’s New Review, Bill Buford’s Granta, the fledgling London Review of Books under Mary-Kay Wilmers and Karl Miller. By the 1980s and 1990s, the culture had decided to make celebrities out of its authors. The agent Andrew Wylie expanded his operations from New York to London and began to extract astronomical advances from an increasingly corporate publishing industry. Tina Brown’s takeover of the New Yorker in 1992, with Buford installed as fiction editor, completed the transatlantic circuit of literary hype.

More here.

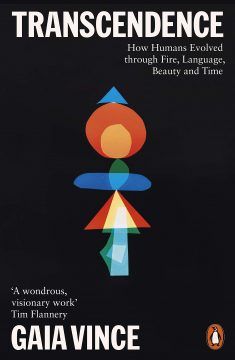

Let’s turn to Transcendence by Gaia Vince, who won the Royal Society science book prize back in 2015 for Adventures in the Anthropocene. What’s her latest book about?

Let’s turn to Transcendence by Gaia Vince, who won the Royal Society science book prize back in 2015 for Adventures in the Anthropocene. What’s her latest book about?

France elected Emmanuel Macron president in 2017 as a symbolic barrier against the rising global tide of illiberal populism. Four years later, as the chaos fomented by U.S. President Donald Trump builds toward some sort of crescendo in the United States, domestic tensions in France threaten to define Macron’s leadership and legacy. The coronavirus pandemic is resurgent, leading the government to institute a strict new lockdown that will continue at least until early December; the mouvement des “gilets jaunes” (“yellow vest” protest movement) has been simmering since late 2018; and a crisis that began in 2015, when Islamist terrorists twice attacked Paris, never went away and has in fact returned with new intensity in recent months.

France elected Emmanuel Macron president in 2017 as a symbolic barrier against the rising global tide of illiberal populism. Four years later, as the chaos fomented by U.S. President Donald Trump builds toward some sort of crescendo in the United States, domestic tensions in France threaten to define Macron’s leadership and legacy. The coronavirus pandemic is resurgent, leading the government to institute a strict new lockdown that will continue at least until early December; the mouvement des “gilets jaunes” (“yellow vest” protest movement) has been simmering since late 2018; and a crisis that began in 2015, when Islamist terrorists twice attacked Paris, never went away and has in fact returned with new intensity in recent months.

The moment every Donald Trump opponent has been waiting for is at hand: Joe Biden seems to be taking the lead. So why am I not happy? I am certainly relieved. A Biden victory would be an infinitely better result than a Trump win. If Trump were to maintain power, our child-king would be unfettered by bothersome laws and institutions. The United States would begin its last days as a democracy, finally stepping over the ledge into authoritarianism. A win for Biden would forestall that terrible possibility.

The moment every Donald Trump opponent has been waiting for is at hand: Joe Biden seems to be taking the lead. So why am I not happy? I am certainly relieved. A Biden victory would be an infinitely better result than a Trump win. If Trump were to maintain power, our child-king would be unfettered by bothersome laws and institutions. The United States would begin its last days as a democracy, finally stepping over the ledge into authoritarianism. A win for Biden would forestall that terrible possibility. Starting in the 1870s, and every year for the past fifteen years, journalists have told and retold the “hidden history” of New York City’s Hart Island, a hundred-acre city cemetery off the coast of the Bronx. Some fields are rolling and green with little white plot markers. Others are fresh brown earth, where individual coffins are buried in communal graves. Where there are not bodies, there are dry stone walls, woodlands, wetlands, and nineteenth-century brick ruins ringed by salt marshes and rubble. For over 150 years, the cemetery has been run as an extension of the prison system, difficult to visit, and this fact tends to capture the imagination.

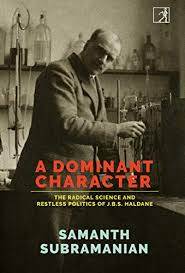

Starting in the 1870s, and every year for the past fifteen years, journalists have told and retold the “hidden history” of New York City’s Hart Island, a hundred-acre city cemetery off the coast of the Bronx. Some fields are rolling and green with little white plot markers. Others are fresh brown earth, where individual coffins are buried in communal graves. Where there are not bodies, there are dry stone walls, woodlands, wetlands, and nineteenth-century brick ruins ringed by salt marshes and rubble. For over 150 years, the cemetery has been run as an extension of the prison system, difficult to visit, and this fact tends to capture the imagination. JBS Haldane – “Jack” to his family and friends – was once described as “the last man who might know all there was to be known”. His reputation was built on his work in genetics, but his expertise was extraordinarily wide-ranging. As an undergraduate at Oxford, he studied mathematics and classics. He never gained any kind of degree in science, but he could explain the latest work in physics, chemistry, biology and a host of other disciplines. He could recite great swathes of poetry in English, French, German, Latin and Ancient Greek. A big man (another description of him is “a large woolly rhinoceros of uncertain temper”), he was unafraid to take anyone on in a fight and, equally, could drink anyone under the table.

JBS Haldane – “Jack” to his family and friends – was once described as “the last man who might know all there was to be known”. His reputation was built on his work in genetics, but his expertise was extraordinarily wide-ranging. As an undergraduate at Oxford, he studied mathematics and classics. He never gained any kind of degree in science, but he could explain the latest work in physics, chemistry, biology and a host of other disciplines. He could recite great swathes of poetry in English, French, German, Latin and Ancient Greek. A big man (another description of him is “a large woolly rhinoceros of uncertain temper”), he was unafraid to take anyone on in a fight and, equally, could drink anyone under the table. When every legally cast vote has been counted, Joe Biden will probably have prevailed in enough states to claim victory in the presidential race, perhaps even ending up with a few more Electoral Votes than Donald Trump managed to earn four years ago. That means Trump will probably be out, defeated in his bid for re-election.

When every legally cast vote has been counted, Joe Biden will probably have prevailed in enough states to claim victory in the presidential race, perhaps even ending up with a few more Electoral Votes than Donald Trump managed to earn four years ago. That means Trump will probably be out, defeated in his bid for re-election. Karachi ranks as having the worst public transport system globally, according to

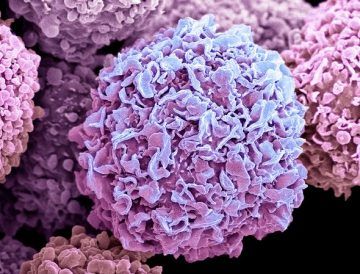

Karachi ranks as having the worst public transport system globally, according to  Improving early cancer detection may be the only way to really put a dent in the cancer mortality curve; however, early cancer detection is suffering from a common ailment in medicine and public health: the streetlight effect. We are looking for five cancers “over here” under the streetlight where we have early detection tests, but about

Improving early cancer detection may be the only way to really put a dent in the cancer mortality curve; however, early cancer detection is suffering from a common ailment in medicine and public health: the streetlight effect. We are looking for five cancers “over here” under the streetlight where we have early detection tests, but about  “SENESCENCE” ISN’T QUITE THE RIGHT WORD for the stage the writers of the Baby Boom have reached. Sure, they may be collecting social security, the eldest of them in their mid-seventies, but the wonders of modern science may allow some another couple of decades of productivity. When the Reaper starts to come for the writer’s instrument, the first thing to go is flow, but that may not matter: fragments are in. In a decade or so, robbed of their transitions and reduced to accumulating prose shards, the octogenarian Boomers may find themselves newly trendy. A strange fate for a generation that entered the literary world at the height of its postmodern excesses: everyone still standing will turn into Lydia Davis.

“SENESCENCE” ISN’T QUITE THE RIGHT WORD for the stage the writers of the Baby Boom have reached. Sure, they may be collecting social security, the eldest of them in their mid-seventies, but the wonders of modern science may allow some another couple of decades of productivity. When the Reaper starts to come for the writer’s instrument, the first thing to go is flow, but that may not matter: fragments are in. In a decade or so, robbed of their transitions and reduced to accumulating prose shards, the octogenarian Boomers may find themselves newly trendy. A strange fate for a generation that entered the literary world at the height of its postmodern excesses: everyone still standing will turn into Lydia Davis. Two years ago, immunologist and medical-publishing entrepreneur Leslie Norins offered to award US$1 million of his own money to any scientist who could prove that Alzheimer’s disease was caused by a germ. The theory that an infection might cause this form of dementia has been rumbling for decades on the fringes of neuroscience research. The majority of Alzheimer’s researchers, backed by a huge volume of evidence, think instead that the key culprits are sticky molecules in the brain called amyloids, which clump into plaques and cause inflammation, killing neurons. Norins wanted to reward work that would make the infection idea more persuasive. The amyloid hypothesis has become “the one acceptable and supportable belief of the Established Church of Conventional Wisdom”, says Norins. “The few pioneers who did look at microbes and published papers were ridiculed or ignored.”

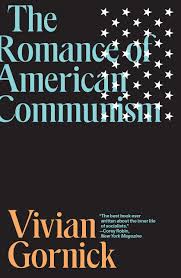

Two years ago, immunologist and medical-publishing entrepreneur Leslie Norins offered to award US$1 million of his own money to any scientist who could prove that Alzheimer’s disease was caused by a germ. The theory that an infection might cause this form of dementia has been rumbling for decades on the fringes of neuroscience research. The majority of Alzheimer’s researchers, backed by a huge volume of evidence, think instead that the key culprits are sticky molecules in the brain called amyloids, which clump into plaques and cause inflammation, killing neurons. Norins wanted to reward work that would make the infection idea more persuasive. The amyloid hypothesis has become “the one acceptable and supportable belief of the Established Church of Conventional Wisdom”, says Norins. “The few pioneers who did look at microbes and published papers were ridiculed or ignored.” In their heyday, the communists were the most political and most intentional of people. That made them often the most terrifying of people, capable of violence on an unimaginable scale. Yet despite—and perhaps also because of—their ruthless sense of purpose, communism contains many lessons for us today. As a new generation of socialists, most born after the Cold War, discovers the challenges of parties and movements and the implications of involvement, the archive of communism, particularly American communism, has become newly relevant. So have two commentaries on that archive: Vivian Gornick’s The Romance of American Communism, originally published in 1977 and reissued this year, and Jodi Dean’s Comrade: An Essay on Political Belonging.

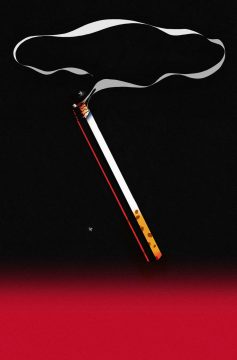

In their heyday, the communists were the most political and most intentional of people. That made them often the most terrifying of people, capable of violence on an unimaginable scale. Yet despite—and perhaps also because of—their ruthless sense of purpose, communism contains many lessons for us today. As a new generation of socialists, most born after the Cold War, discovers the challenges of parties and movements and the implications of involvement, the archive of communism, particularly American communism, has become newly relevant. So have two commentaries on that archive: Vivian Gornick’s The Romance of American Communism, originally published in 1977 and reissued this year, and Jodi Dean’s Comrade: An Essay on Political Belonging. Immanuel Kant, who smoked a pipe of tobacco with his tea once or twice a day, described the aesthetic category of the sublime as a “negative pleasure”: “incompatible with charms,” as “the mind is not just attracted by the object but is alternately always repelled as well.” Not unlike the feeling of respect, sublimity is greeted by the Kantian subject with a manic combination of satisfaction and fear, a sense of pride in the superiority of human intellect at the expense of imaginative and physical fallibility. A frisson of euphoria and disgust, or as Richard Klein writes in Cigarettes Are Sublime, “a darkly beautiful, inevitably painful pleasure that arises from some intimation of eternity.” The “taste of infinity in a cigarette” presents to the smoker a philosophical “edge of the abyss”: mortality, selfhood, existence. For Annie Leclerc, in Au feu du jour, “the cigarette is the prayer of our time.”

Immanuel Kant, who smoked a pipe of tobacco with his tea once or twice a day, described the aesthetic category of the sublime as a “negative pleasure”: “incompatible with charms,” as “the mind is not just attracted by the object but is alternately always repelled as well.” Not unlike the feeling of respect, sublimity is greeted by the Kantian subject with a manic combination of satisfaction and fear, a sense of pride in the superiority of human intellect at the expense of imaginative and physical fallibility. A frisson of euphoria and disgust, or as Richard Klein writes in Cigarettes Are Sublime, “a darkly beautiful, inevitably painful pleasure that arises from some intimation of eternity.” The “taste of infinity in a cigarette” presents to the smoker a philosophical “edge of the abyss”: mortality, selfhood, existence. For Annie Leclerc, in Au feu du jour, “the cigarette is the prayer of our time.”