Lydia Syson in Aeon:

Five years had passed since Czar Alexander II promised the emancipation of the serfs. Trusting in a map drawn on bark with the point of a knife by a Tungus hunter, three Russian scientists set out to explore an area of trackless mountain wilderness stretching across eastern Siberia. Their mission was to find a direct passage between the gold mines of the river Lena and Transbaikalia. Their discoveries would transform understanding of the geography of northern Asia, opening up the route eventually followed by the Trans-Manchurian Railway. For one explorer, now better known as an anarchist than a scientist, this expedition was also the start of a long journey towards a new articulation of evolution and the strongest possible argument for a social revolution.

Five years had passed since Czar Alexander II promised the emancipation of the serfs. Trusting in a map drawn on bark with the point of a knife by a Tungus hunter, three Russian scientists set out to explore an area of trackless mountain wilderness stretching across eastern Siberia. Their mission was to find a direct passage between the gold mines of the river Lena and Transbaikalia. Their discoveries would transform understanding of the geography of northern Asia, opening up the route eventually followed by the Trans-Manchurian Railway. For one explorer, now better known as an anarchist than a scientist, this expedition was also the start of a long journey towards a new articulation of evolution and the strongest possible argument for a social revolution.

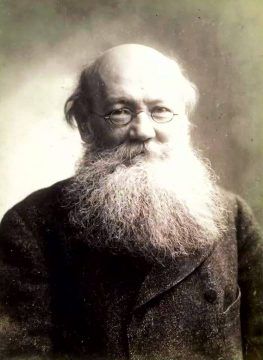

Prince Peter Kropotkin, the aristocratic graduate of an elite Russian military academy, travelled in 1866 with his zoologist friend Ivan Poliakov and a topographer called Maskinski. Boat and horseback took them to the Tikono-Zadonsk gold mine. From there, they continued with 10 Cossacks, 50 horses carrying three months’ supply of food, and an old Yukaghir nomad guide who’d made the journey 20 years earlier.

Kropotkin and Poliakov – enthusiastic, curious and well-read young men in their 20s – were fired by the prospect of finding evidence of that defining factor of evolution set out by Charles Darwin in On the Origin of Species (1859): competition. They were disappointed.

More here.