The upper fortress of Franzensfeste, South Tyrol, in November of 2020.

Month: November 2020

Film Review: ‘Zappa’ Captures a Maverick’s Essence

by Alexander C. Kafka

What is it about Frank Zappa’s eyes? They leer. They challenge. They invite play and fun and nonsense. But they’re also afraid. They don’t look away. They fix on you defiantly as if he’s expecting to be slapped for something naughty that he said. And he said many naughty things.

One sees a lot of those hypnotizing eyes in the superb new documentary Zappa, directed by Alex Winter. Yes, that Alex Winter, of Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, who is also the serious-minded director of documentaries on the Panama Papers and blockchain. Creating Zappa was an adventure in itself — five years in the making, with access to the artist’s archives and cooperation from the family and a slew of Zappa’s fellow musicians. It was funded through the largest crowdsourced campaign ever for a documentary. Eight-thousand backers invested $1.2 million. It’s the kind of free enterprise Zappa would have applauded.

Winter’s is a wild, often melancholy portrait of a counterculture hero who, in 1993, died from prostate cancer at age 52. It strengthens the case suggested by the 115 albums of Zappa’s music — 53 of them posthumous — that he was a multi-genre composer for whom rock stardom and guitar virtuosity were tools, not ends in themselves. He was also a visual artist, filmmaker, audio innovator, First Amendment freedom fighter, and proud entrepreneur. Zappa produced and briefly even distributed his own material. He also produced albums for Alice Cooper, the GTOs, Zappa’s high-school buddy Captain Beefheart, and other musicians, as well as an album from Lenny Bruce’s last live performance.

Why Wine Tasting Notes are Not Helpful

by Dwight Furrow

Look on the back label of most wine bottles and you will find a tasting note that reads like a fruit basket—a list of various fruit aromas along with a few herb and oak-derived aromas that consumers are likely to find with some more or less dedicated sniffing. You will find a more extensive list of aromas if you visit the winery’s website and find the winemaker’s notes or read wine reviews published in wine magazines or online.

Look on the back label of most wine bottles and you will find a tasting note that reads like a fruit basket—a list of various fruit aromas along with a few herb and oak-derived aromas that consumers are likely to find with some more or less dedicated sniffing. You will find a more extensive list of aromas if you visit the winery’s website and find the winemaker’s notes or read wine reviews published in wine magazines or online.

Here is one typical example of a winemaker’s note:

The 2016 Monterey Pinot Noir has bright cherry aromas that are layered with notes of wild strawberries and black tea. On the palate, you get juicy, black cherry flavors and notes of cola with hints of vanilla, toasted oak, and well-balanced tannins. A silky texture leads to a long finish.

The purpose of tasting notes is apparently to give prospective consumers an idea of what the wine will smell and taste like. And they succeed up to a point. Wine’s do exhibit aromas such as black cherry, cola, and vanilla.

But do notes like this give you much information about the quality of the wine or what a particular wine has to offer that is worthy of your attention? Read more »

Philosophy’s Failure to Do Nature Justice

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

Among the Domitian questions I enjoy freely pondering, I sometimes wonder how our religious and metaphysical representations of the afterlife would be different if, rather than dying and leaving a rotting corpse for others to dispose of, we instead disappeared in a flash of light, or floated upwards into the sky and out beyond the atmosphere. It recently occurred to me that this latter scenario is at least something like what whales experience when their loved ones die.

Among the Domitian questions I enjoy freely pondering, I sometimes wonder how our religious and metaphysical representations of the afterlife would be different if, rather than dying and leaving a rotting corpse for others to dispose of, we instead disappeared in a flash of light, or floated upwards into the sky and out beyond the atmosphere. It recently occurred to me that this latter scenario is at least something like what whales experience when their loved ones die.

We think of aquatic animals as being able to move freely not just to and fro, but also up and down. In fact most are confined to a fairly narrow zone outside of which they could not survive, either because of the adaptation of their bodies to a particular amount of water pressure, their need for light or for the absence of light, or some other reason still. Most cetacean species inhabit a narrow band of water between the surface and the mesopelagic zone, characterised by a certain amount of light, but no photosynthetic microorganisms. Blue whales, a fairly average species in this regard, can dive to about 300 metres. Sperm whales and certain beaked whales hold the deep-dive record, descending 2500 metres or so to hunt for giant squid and other prey in the abyssopelagic zone.

More here.

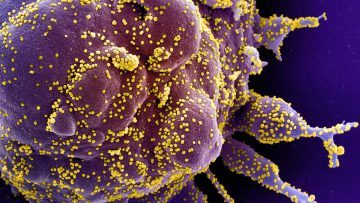

Will the Coronavirus Evolve to Be Less Deadly?

Wendy Orent in Undark:

As far as scientists and historians can tell, the bacterium that caused the Black Death never lost its virulence, or deadliness. But the pathogen responsible for the 1918 influenza pandemic, which still wanders the planet as a strain of seasonal flu, evolved to become less deadly, and it’s possible that the pathogen for the 2009 H1N1 pandemic did the same. Will SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, follow a similar trajectory? Some scientists say the virus has already evolved in a way that makes it easier to transmit. But as for a possible decline in virulence, most everyone says it’s too soon to tell. Looking to the past, however, may offer some clues.

As far as scientists and historians can tell, the bacterium that caused the Black Death never lost its virulence, or deadliness. But the pathogen responsible for the 1918 influenza pandemic, which still wanders the planet as a strain of seasonal flu, evolved to become less deadly, and it’s possible that the pathogen for the 2009 H1N1 pandemic did the same. Will SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, follow a similar trajectory? Some scientists say the virus has already evolved in a way that makes it easier to transmit. But as for a possible decline in virulence, most everyone says it’s too soon to tell. Looking to the past, however, may offer some clues.

The idea that circulating pathogens gradually become less deadly over time is very old. It seems to have originated in the writings of a 19th-century physician, Theobald Smith, who first suggested that there is a “delicate equilibrium” between parasite and host, and argued that, over time, the deadliness of a pathogen should decline since it is really not in the interest of a germ to kill its host. This notion became conventional wisdom for many years, but by the 1980s, researchers had begun challenging the idea.

More here.

The Rise of Vetocracy

Eric B. Schnurer in The Hedgehog Review:

Government has descended into near-permanent deadlock. The resulting populist movements, on both the right and left, are highly democratic: intensely broad-based and grassroots, and at least rhetorically anti-elite. But they are neither liberal nor tolerant. On an operational level, it has become more important to “own the libs” or “cancel conservatives” than to achieve any meaningful objective, let alone compromise. All opposition is now treated as an existential threat.

Government has descended into near-permanent deadlock. The resulting populist movements, on both the right and left, are highly democratic: intensely broad-based and grassroots, and at least rhetorically anti-elite. But they are neither liberal nor tolerant. On an operational level, it has become more important to “own the libs” or “cancel conservatives” than to achieve any meaningful objective, let alone compromise. All opposition is now treated as an existential threat.

Yet the increasing acceptance of incivility, the denigration and ridicule of opponents, the political violence and even death threats against anyone who takes a position that someone dislikes isn’t the problem itself. It’s simply the iceberg’s tip of a deeper and larger social phenomenon that constitutes our new normal. That new normal, in short, rather than either autocracy or democracy, is vetocracy: Thomas Hobbes’s “state of nature,” but one in which weak and strong alike can thwart each other’s objectives yet none can attain their own.

More here.

The Angst of America

Adil Najam in Dawn:

Historic is not a word that should be used lightly. It should nearly never be used for anything contemporary and only sparingly for events long past. Yet, it is being used with considerable frequency to describe the 2020 US Presidential elections; maybe, not inappropriately.

Historic is not a word that should be used lightly. It should nearly never be used for anything contemporary and only sparingly for events long past. Yet, it is being used with considerable frequency to describe the 2020 US Presidential elections; maybe, not inappropriately.

But leaving judgements of history to history, as we should, does not diminish the truly exceptional importance of these elections. Not just because of the trauma of the presidency they bring to an end, but even more for the turbulent times that they foretell ahead.

Even before the election results began coming in, it had become commonplace to describe America as divided. It is, in fact, so. But these elections — in their run-up as well as in their results — have also revealed the inadequacy of that word. Maybe angst is a better word to describe the state of this Union. This essay argues that the 2020 US elections have not only confirmed that Mr Trump leaves America in the grip of an epoch-defining angst, but that this angst will continue, possibly intensify, into the Biden presidency.

Here are three reasons why.

More here.

Understanding the Trump voters: Here’s why nobody is doing it right

Nathaniel Manderson in Salon:

Based on the last two presidential elections, there is clearly a failure in reporting, polling and understanding of almost half of America. Perhaps liberals would simply like to govern and run for office by only mobilizing their half of the population and overlooking that other half, but I would imagine this country won’t get closer to equal opportunity with that type of thinking. It’s true that much of the divisive language comes from Trump supporters who seems to enjoy Trump’s deplorable approach to life and politics. Does that embody every single person who voted for Donald Trump in the last two elections? If you think that, then you are as lost as the narrow reporting and polling I have witnessed during the last four years.

Based on the last two presidential elections, there is clearly a failure in reporting, polling and understanding of almost half of America. Perhaps liberals would simply like to govern and run for office by only mobilizing their half of the population and overlooking that other half, but I would imagine this country won’t get closer to equal opportunity with that type of thinking. It’s true that much of the divisive language comes from Trump supporters who seems to enjoy Trump’s deplorable approach to life and politics. Does that embody every single person who voted for Donald Trump in the last two elections? If you think that, then you are as lost as the narrow reporting and polling I have witnessed during the last four years.

My life has brought me across the lives of many other people, which has allowed me to understand the viewpoints of both sides in a more personal and complicated way. I’m a former pastor, and my favorite family in one of my churches was one that actually attended a Glenn Beck rally. Do you realize how kooky you need to be to travel from Massachusetts to Washington, D.C., to attend a Glenn Beck rally as a family? Yet I have nothing but warm feelings for them: Best family in the church by far. They were close to each other, kind and down to earth — and as far from me politically as anyone I have ever met. My least favorite family was full of hate, judgment and self-righteousness — yet I agreed with them on every single political issue. In fact, that liberal family is the sole reason I left formal ministry.

More here.

14 fun facts about Princess Diana’s wedding

Meilan Solly in Smithsonian:

When Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer exchanged vows on July 29, 1981, the archbishop officiating the ceremony declared, “Here is the stuff of which fairy tales are made—the prince and princess on their wedding day.” Departing from the standard storybook ending of “they lived happily ever after,” he continued, “Our [Christian] faith sees the wedding day not as the place of arrival, but the place where the adventure really begins.”

When Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer exchanged vows on July 29, 1981, the archbishop officiating the ceremony declared, “Here is the stuff of which fairy tales are made—the prince and princess on their wedding day.” Departing from the standard storybook ending of “they lived happily ever after,” he continued, “Our [Christian] faith sees the wedding day not as the place of arrival, but the place where the adventure really begins.”

For the 32-year-old heir to the British throne and his 20-year-old bride, this assessment proved eerily prescient. Idolized by an adoring public, the newly minted Princess Diana found herself thrust into the spotlight, cast as Cinderella to Charles’ Prince Charming. But beneath this mirage of marital bliss, the royal family was in crisis—a history dramatized in the fourth season of Netflix’s “The Crown,” which follows Elizabeth II (Olivia Colman) and Prince Philip (Tobias Menzies) as they navigate the events of 1979 to 1990, from Charles’ (Josh O’Connor) courtship of Diana (Emma Corrin) to Margaret Thatcher’s (Gillian Anderson) tenure as prime minister and the Falklands War.

Looming over the season, too, is the eventual dissolution of Charles and Diana’s relationship. The prince remained enamored with his ex-girlfriend, Camilla Parker Bowles, and in 1986, when Charles decided that his marriage had “irretrievably broken down,” the former couple embarked on an affair. Diana also started seeing other men, and the royals formally divorced in 1996 after a four-year separation. One year later, the beloved princess died in a car crash. Ahead of the new episodes’ arrival this Sunday, November 15, here’s what you need to know about arguably the most anticipated event of the season: the royal wedding.

More here.

David Toole (1964 – 2020)

Aldo Tambellini (1930 – 2020)

Lynn Kellogg (1944 – 2020)

Hou Hsiao-hsien, Chu Tien-wen and Olivier Assayas

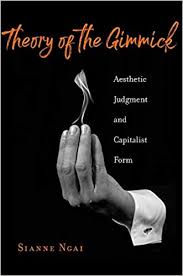

Our Love-Hate Relationship with Gimmicks

Merve Emre at The New Yorker:

Although Ngai’s books are conceptually and philosophically dense, their appeal comes from how they tap into our ordinary use of language. Unless I collect art, or live in a many-windowed house at the edge of a westerly peninsula, where the sea is gilded by the sun and silvered by the moon, I am unlikely to have regular encounters with things I would call “beautiful” or “sublime,” and I may well find the rush and roar of such Romantic descriptions embarrassing. But not a day goes by when I do not call something—my son’s stuffed animals, a dress, a poem by Gertrude Stein—“cute,” or a novel or an essay “interesting.” And I can’t count the number of times I’ve called a kitchen gizmo my husband swears we really, really need (but we really, really don’t) or a colleague’s online persona “gimmicky.” “Theory of the Gimmick” finds in the pervasiveness of the gimmick the same duelling forces of aesthetic attraction and repulsion that shape all Ngai’s work. “ ‘You want me,’ the gimmick outrageously says,” she writes. “It is never entirely wrong.”

Although Ngai’s books are conceptually and philosophically dense, their appeal comes from how they tap into our ordinary use of language. Unless I collect art, or live in a many-windowed house at the edge of a westerly peninsula, where the sea is gilded by the sun and silvered by the moon, I am unlikely to have regular encounters with things I would call “beautiful” or “sublime,” and I may well find the rush and roar of such Romantic descriptions embarrassing. But not a day goes by when I do not call something—my son’s stuffed animals, a dress, a poem by Gertrude Stein—“cute,” or a novel or an essay “interesting.” And I can’t count the number of times I’ve called a kitchen gizmo my husband swears we really, really need (but we really, really don’t) or a colleague’s online persona “gimmicky.” “Theory of the Gimmick” finds in the pervasiveness of the gimmick the same duelling forces of aesthetic attraction and repulsion that shape all Ngai’s work. “ ‘You want me,’ the gimmick outrageously says,” she writes. “It is never entirely wrong.”

more here.

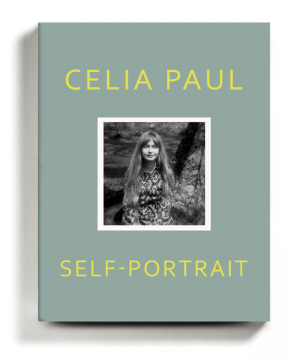

Celia Paul on Lucian Freud, Motherhood and a Life in Art

Jennifer Szalai at the NYT:

“Self-Portrait” is Paul’s account of her life and her work — or, more precisely, of her attempts to realize the possibilities of each despite the constraints thrown up by the other. She left Frank with her mother in Cambridge when he was an infant. When Paul spends time with him, she says, “I don’t have any thoughts for myself.” She lives separately from her current husband, who doesn’t have a key to her flat.

“Self-Portrait” is Paul’s account of her life and her work — or, more precisely, of her attempts to realize the possibilities of each despite the constraints thrown up by the other. She left Frank with her mother in Cambridge when he was an infant. When Paul spends time with him, she says, “I don’t have any thoughts for myself.” She lives separately from her current husband, who doesn’t have a key to her flat.

Paul writes about her struggle to love someone while dedicating herself to her painting, explaining in her prologue that she hopes her book will “speak to young women artists — and perhaps to all women — who will no doubt face this challenge in their lives at some time and will have to resolve this conflict in their own ways.” But this makes her mesmerizing book sound more helpful than it is, or than it needs to be; “Self-Portrait” is less tidy and more surprising than such a potted purpose would allow.

more here.

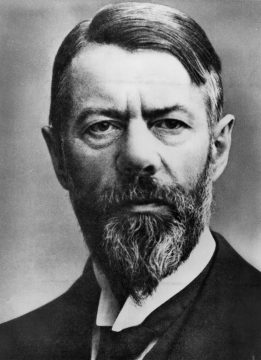

The Professor and the Politician

Corey Robin in The New Yorker:

Corey Robin in The New Yorker:

he professor and the politician are a dyad of perpetual myth. In one myth, they are locked in conflict, sparring over the claims of reason and the imperative of power. Think Socrates and Athens, or Noam Chomsky and the American state. In another myth, they are reconciled, even fused. The professor becomes a politician, saving the polity from corruption and ignorance, demagoguery and vice. Think Plato’s philosopher-king, or Aaron Sorkin’s Jed Bartlet. The nobility of ideas is preserved, and transmuted, slowly, into the stuff of action.

The sociologist Max Weber spent much of his life seduced by this second fable. A scholar of hot temper and volcanic energy, Weber longed to be a politician of cold focus and hard reason. Across three decades of a scholarly career, in Wilhelmine and Weimar Germany, he made repeated and often failed incursions into the public sphere—to give advice, stand for office, form a party, negotiate a treaty, and write a constitution. His “secret love,” he confessed to a friend, was “the political.” Even in the delirium of his final days, he could be heard declaiming on behalf of the German people, jousting with their enemies in several of the many languages he knew. “If one is lucky” in politics, he observed, a “genius appears just once every few hundred years.” That left the door wide open for him.

More here. And see also Patrick Thaddeus Jackson’s response over at Lawyers, Guns and Money:

1) The whole point of Weber’s “vocation” lectures was to caution his listeners against either a political or an academic “savior.” In the lecture on Wissenschaft — usually translated “science,” but the sense of the word in German is more like “systematic scholarship” — Weber takes pains to argue that other than “some overgrown children in their professorial chairs or editorial offices,” no one thinks that academic study can teach us anything about the meaning of the world. And in the lecture on politics, Weber is, if anything, more afraid of the revolutionary prophet taking over the reins of government than he is of the amoral cynic who treats politics as a means for personal enrichment:

“…people who have just preached ‘love against force’ are found calling for the use of force the very next moment. It is always the very last use of force that will then bring about a situation in which all violence will have been destroyed — just as our military leaders tell the soldiers that every offensive will be the last. This one will bring victory and then peace. The man who embraces an ethics of conviction is unable to tolerate the ethical irrationality of the world.”

More here.

The subjective turn

Jon Stewart in Aeon:

Jon Stewart in Aeon:

What is the human being? Traditionally, it was thought that human nature was something fixed, given either by nature or by God, once and for all. Humans occupy a unique place in creation by virtue of a specific combination of faculties that they alone possess, and this is what makes us who we are. This view comes from the schools of ancient philosophy such as Platonism, Aristotelianism and Stoicism, as well as the Christian tradition. More recently, it has been argued that there is actually no such thing as human nature but merely a complex set of behaviours and attitudes that can be interpreted in different ways. For this view, all talk of a fixed human nature is merely a naive and convenient way of discussing the human experience, but doesn’t ultimately correspond to any external reality. This view can be found in the traditions of existentialism, deconstruction and different schools of modern philosophy of mind.

There is, however, a third approach that occupies a place between these two. This view, which might be called historicism, claims that there is a meaningful conception of human nature, but that it changes over time as human society develops. This approach is most commonly associated with the German philosopher G W F Hegel (1770-1831). He rejects the claim of the first view, that of the essentialists, since he doesn’t think that human nature is something given or created once and for all. But he also rejects the second view since he doesn’t believe that the notion of human nature is just an outdated fiction we’ve inherited from the tradition. Instead, Hegel claims that it’s meaningful and useful to talk about the reality of some kind of human nature, and that this can be understood by an analysis of human development in history.

More here.

Beyond price stability with Daniela Gabor, Christian Odendahl, Philippa Sigl-Glöckner & Adam Tooze

Conversation with a Native Son: Maya Angelou and James Baldwin

Saturday Poem

Embryo

All morning, pitting the apricots

to make marmalade. All morning

opening them to remove the swollen,

warm ovum that grows inside

the flesh: scattering of silent apricots

picked over on the antiseptic kitchen

counter. As if she were the head nurse,

grandma boils the pot

with two fingers of sugared water.

The girl runs in and pockets

the pits nobody wants. Under the white

encouragement of the myrtle tree, she rubs

the woody pit against the wall’s rough

bumps, and listens to a languid whistle

rising from the depths of the unborn embryo,

from the afternoon rising up, from the blood,

from doubt—years to come,

years to become.

by Gemma Gorga

from Plume Magazine