Paige K. Bradley at Artforum:

To fixate on the question of Q’s identity would be, in the conspiracist’s parlance, to chase a false flag. And a group curiously close to Q would likely say the same: the leftist Italian literary collective Wu Ming, a pseudonym translating to “anonymous” or “no name,” which was formed in 2000 as an outgrowth of Luther Blissett, a nom de plume for the same circle of coauthors. In 1999, Blissett published Q, a historical-adventure novel set during the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation that follows an anonymous Anabaptist radical as he is pursued around Europe by Q, a Roman Catholic spy. In a December 2002 essay posted to its website, Wu Ming declared, “We are interested in ﹡mythopoesis﹡, i.e. the social process of constructing myths, by which we do not mean ‘false stories,’ we mean stories that are told and shared, re-told and manipulated, by a vast and multifarious community, stories that may give shape to some kind of ritual, some sense of continuity between what we do and what other people did in the past. A tradition.” This sounds uncannily similar to QAnon’s story for the people. Q often claims that “Future proves past,” setting its readers up to understand time as a circular process, and, in a sense, it’s not wrong. Time ceases to be progressive in Q’s realm, and on the world stage, ancient crimes and sins are eternally recurring eruptions that must be quashed anew by righteous armies in recycled costumery. Anyone with a taste for devotion and a capacity for faith is a potential conscript. Someone, somewhere, is laughing their head off at their joke, having inflamed all sides in a war for what’s true and who’s accountable for it. No need to bother with guillotines when heads are already lost. And here fall the rest of us down rabbit holes that never end, while others await the longed-for storm, not realizing they have drowned beneath its waves.

To fixate on the question of Q’s identity would be, in the conspiracist’s parlance, to chase a false flag. And a group curiously close to Q would likely say the same: the leftist Italian literary collective Wu Ming, a pseudonym translating to “anonymous” or “no name,” which was formed in 2000 as an outgrowth of Luther Blissett, a nom de plume for the same circle of coauthors. In 1999, Blissett published Q, a historical-adventure novel set during the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation that follows an anonymous Anabaptist radical as he is pursued around Europe by Q, a Roman Catholic spy. In a December 2002 essay posted to its website, Wu Ming declared, “We are interested in ﹡mythopoesis﹡, i.e. the social process of constructing myths, by which we do not mean ‘false stories,’ we mean stories that are told and shared, re-told and manipulated, by a vast and multifarious community, stories that may give shape to some kind of ritual, some sense of continuity between what we do and what other people did in the past. A tradition.” This sounds uncannily similar to QAnon’s story for the people. Q often claims that “Future proves past,” setting its readers up to understand time as a circular process, and, in a sense, it’s not wrong. Time ceases to be progressive in Q’s realm, and on the world stage, ancient crimes and sins are eternally recurring eruptions that must be quashed anew by righteous armies in recycled costumery. Anyone with a taste for devotion and a capacity for faith is a potential conscript. Someone, somewhere, is laughing their head off at their joke, having inflamed all sides in a war for what’s true and who’s accountable for it. No need to bother with guillotines when heads are already lost. And here fall the rest of us down rabbit holes that never end, while others await the longed-for storm, not realizing they have drowned beneath its waves.

more here.

Burke’s story is ultimately one of decline, from the ‘monsters of erudition’ of the 17th century to the present era of specialisation. Early modernists may feel that he is slightly cheating in his description of their period by setting up as separate disciplines subjects that were always studied together. For example, optics, astronomy and geometry were all part of ‘mathematics’, and it was effectively impossible to specialise in only one of them; in these terms, anyone who practised the subject was a polymath. This being admitted, some figures omitted here seem more worthy of inclusion than others who do appear: for example, the Flemish Simon Stevin made seminal contributions to pure and applied mathematics, as well as engineering, music theory and bookkeeping, while also practising chemistry, among many other disciplines.

Burke’s story is ultimately one of decline, from the ‘monsters of erudition’ of the 17th century to the present era of specialisation. Early modernists may feel that he is slightly cheating in his description of their period by setting up as separate disciplines subjects that were always studied together. For example, optics, astronomy and geometry were all part of ‘mathematics’, and it was effectively impossible to specialise in only one of them; in these terms, anyone who practised the subject was a polymath. This being admitted, some figures omitted here seem more worthy of inclusion than others who do appear: for example, the Flemish Simon Stevin made seminal contributions to pure and applied mathematics, as well as engineering, music theory and bookkeeping, while also practising chemistry, among many other disciplines. Among the many rules for the conduct of life that Pythagoras passed down to members of his philosophical cult, there is a peculiar prohibition that keeps coming up in late-antique testimonia: Consume no lentils. Decline all lupins. Eat not pulses. Abstain from beans. Different authors provide different rationales for this (Diogenes Laërtius says that it is because beans resemble testicles, and perhaps also the gates of Hades), but we may isolate three of them as the most common and most compelling. First, you must not eat beans because they produce within you an undesirable flatus, damaging to your health and noxious to those around you. Second, you must not eat beans for the same reason you must not eat meat — they too are ensouled, and may well harbour the particular souls of your reincarnated love ones.

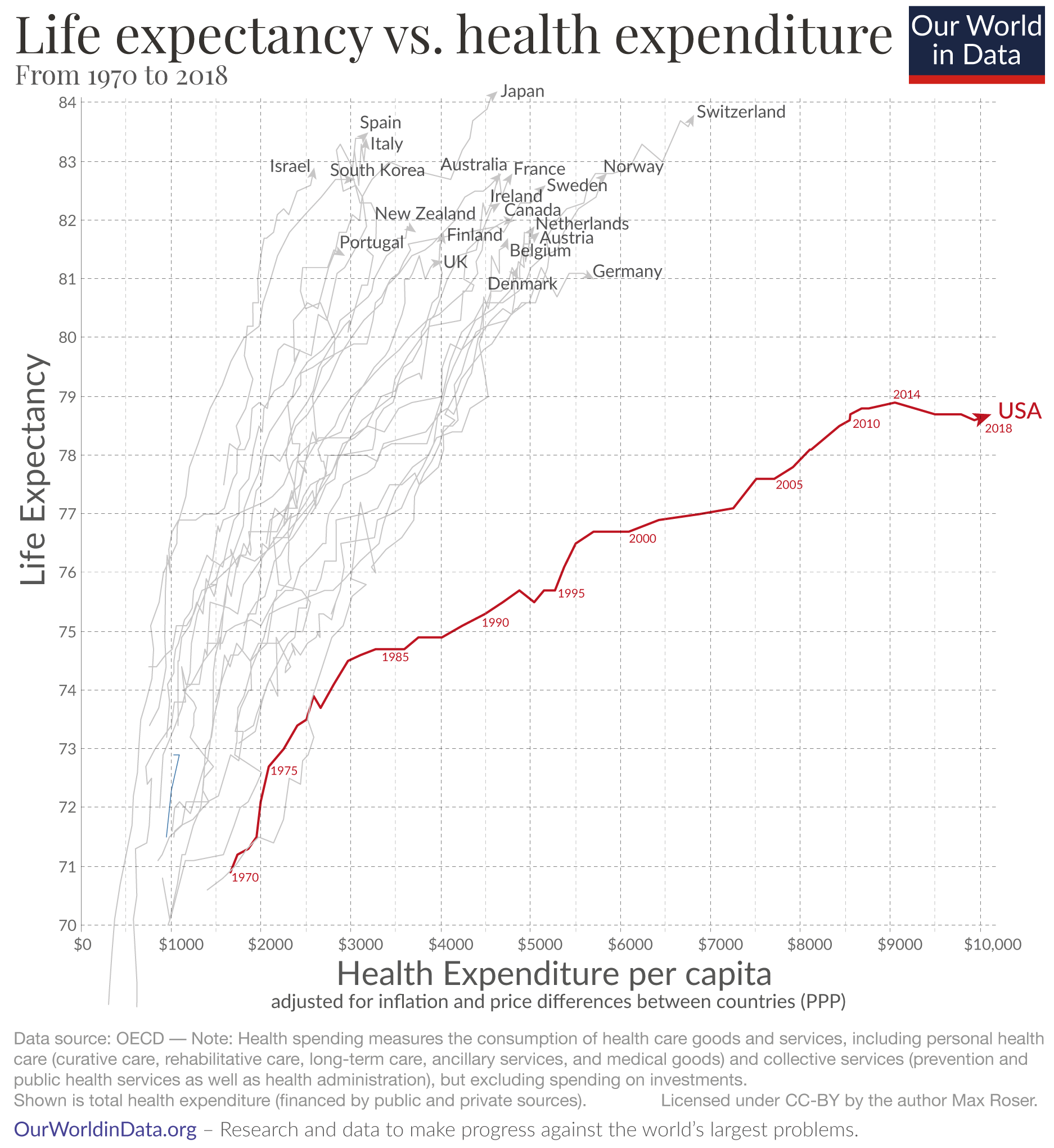

Among the many rules for the conduct of life that Pythagoras passed down to members of his philosophical cult, there is a peculiar prohibition that keeps coming up in late-antique testimonia: Consume no lentils. Decline all lupins. Eat not pulses. Abstain from beans. Different authors provide different rationales for this (Diogenes Laërtius says that it is because beans resemble testicles, and perhaps also the gates of Hades), but we may isolate three of them as the most common and most compelling. First, you must not eat beans because they produce within you an undesirable flatus, damaging to your health and noxious to those around you. Second, you must not eat beans for the same reason you must not eat meat — they too are ensouled, and may well harbour the particular souls of your reincarnated love ones. Why do Americans have a lower life expectancy than people in other rich countries, despite paying so much more for health care?

Why do Americans have a lower life expectancy than people in other rich countries, despite paying so much more for health care? Esa-Pekka Salonen didn’t expect to make his entrance at the San Francisco Symphony with a virtual premiere.

Esa-Pekka Salonen didn’t expect to make his entrance at the San Francisco Symphony with a virtual premiere. The word “relevant,” I was recently surprised to discover, shares an etymology with the word “relieve.” This seems obvious enough once you know it—only a few letters separate the words—but their usages diverged so long ago that I had never associated them before. Searching out etymologies is an old habit, picked up in the decades when I aspired to be a poet. Language is fossil poetry, Emerson says, and the poem the Oxford English Dictionary lays out in this case is remarkably moving. The common forebear of both “relevant” and “relieve” is the French relever, which meant, originally, to put back into an upright position, to raise again, a word that twisted through time, scattering meanings that our two modern words have apportioned between them: to ease pain or discomfort, to make stand out, to render prominent or distinct, to rise up or rebel, to rebuild, to reinvigorate, to make higher, to set free.

The word “relevant,” I was recently surprised to discover, shares an etymology with the word “relieve.” This seems obvious enough once you know it—only a few letters separate the words—but their usages diverged so long ago that I had never associated them before. Searching out etymologies is an old habit, picked up in the decades when I aspired to be a poet. Language is fossil poetry, Emerson says, and the poem the Oxford English Dictionary lays out in this case is remarkably moving. The common forebear of both “relevant” and “relieve” is the French relever, which meant, originally, to put back into an upright position, to raise again, a word that twisted through time, scattering meanings that our two modern words have apportioned between them: to ease pain or discomfort, to make stand out, to render prominent or distinct, to rise up or rebel, to rebuild, to reinvigorate, to make higher, to set free. The world watched today

The world watched today Could one vote — your vote — swing an entire election? Most of us abandoned this seeming fantasy not too long after we learned how elections work.

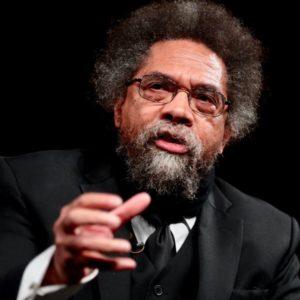

Could one vote — your vote — swing an entire election? Most of us abandoned this seeming fantasy not too long after we learned how elections work. This episode is published on November 2, 2020, the day before an historic election in the United States. An election that comes amidst growing worries about the future of democratic governance, as well as explicit claims that democracy is intrinsically unfair, inefficient, or ill-suited to the modern world. What better time to take a step back and think about the foundations of democracy? Cornel West is a well-known philosopher and public intellectual who has written extensively about race and class in America. He is also deeply interested in democracy, both in theory and in practice. We talk about what makes democracy worth fighting for, the different traditions that inform it, and the kinds of engagement it demands of its citizens.

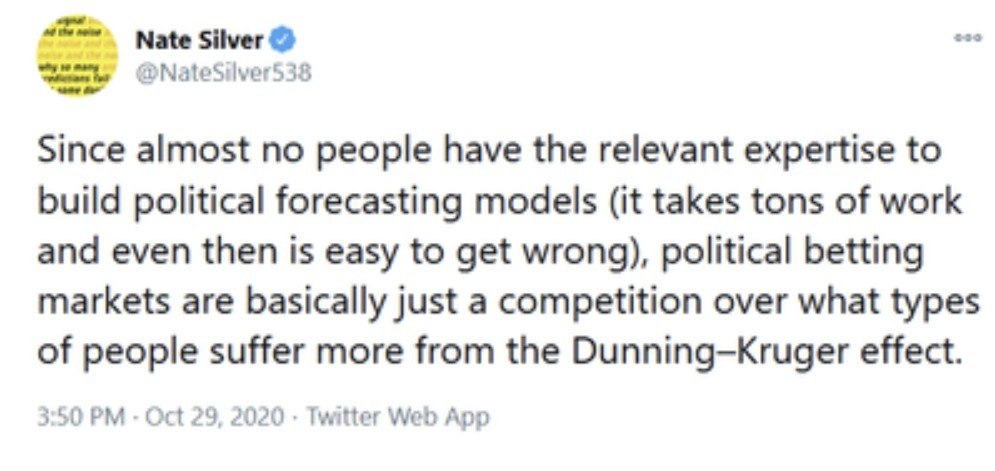

This episode is published on November 2, 2020, the day before an historic election in the United States. An election that comes amidst growing worries about the future of democratic governance, as well as explicit claims that democracy is intrinsically unfair, inefficient, or ill-suited to the modern world. What better time to take a step back and think about the foundations of democracy? Cornel West is a well-known philosopher and public intellectual who has written extensively about race and class in America. He is also deeply interested in democracy, both in theory and in practice. We talk about what makes democracy worth fighting for, the different traditions that inform it, and the kinds of engagement it demands of its citizens. But this year, the betting and prediction markets differ sharply. The betting markets see a 34 percent chance of a Trump victory, while the prediction models see but a 5 to 10 percent chance. So who should we believe?

But this year, the betting and prediction markets differ sharply. The betting markets see a 34 percent chance of a Trump victory, while the prediction models see but a 5 to 10 percent chance. So who should we believe? The unmasking of the bourgeois belief in objective reality has been so fully accomplished in America that any meaningful struggle against reality has become absurd.” Anyone reading this might think it a criticism of America. The lack of a sense of reality is a dangerous weakness in any country. Before the revolutions of 1917, Tsarist Russia was ruled by a class oblivious to existential threats within its own society. An atmosphere of unreality surrounded the rise of Nazism in Germany – a deadly threat that Britain and other countries failed to perceive until it was almost too late.

The unmasking of the bourgeois belief in objective reality has been so fully accomplished in America that any meaningful struggle against reality has become absurd.” Anyone reading this might think it a criticism of America. The lack of a sense of reality is a dangerous weakness in any country. Before the revolutions of 1917, Tsarist Russia was ruled by a class oblivious to existential threats within its own society. An atmosphere of unreality surrounded the rise of Nazism in Germany – a deadly threat that Britain and other countries failed to perceive until it was almost too late. Recently opened bookstore in southwest China looks like it came straight out of one of Dutch artist

Recently opened bookstore in southwest China looks like it came straight out of one of Dutch artist  And yet, despite this vision of dreams as paradigmatically distant, many of the world’s cultures—especially outside of the modern West—have developed elaborate protocols by which dreams can be shared. The complexity of these protocols is confirmation, in one sense, of the claim that dreams are especially private, even more so than other forms of thinking. A society must work very hard indeed to make them sharable; they must be wrestled into this life from that nighttime one. But these protocols are also somehow a rebuke to the philosophers’ skepticism: people build their own universes in dreams, except, as we’ll see, they then go to great lengths to reconstruct and combine them into a shared one while awake. This seems to raise at least two questions. Why go to such great lengths to share dreams? And what happens to a culture, like our own, that doesn’t practice dream sharing, that (a few isolated realms aside, perhaps the most important being psychoanalysis) has largely given up on it?

And yet, despite this vision of dreams as paradigmatically distant, many of the world’s cultures—especially outside of the modern West—have developed elaborate protocols by which dreams can be shared. The complexity of these protocols is confirmation, in one sense, of the claim that dreams are especially private, even more so than other forms of thinking. A society must work very hard indeed to make them sharable; they must be wrestled into this life from that nighttime one. But these protocols are also somehow a rebuke to the philosophers’ skepticism: people build their own universes in dreams, except, as we’ll see, they then go to great lengths to reconstruct and combine them into a shared one while awake. This seems to raise at least two questions. Why go to such great lengths to share dreams? And what happens to a culture, like our own, that doesn’t practice dream sharing, that (a few isolated realms aside, perhaps the most important being psychoanalysis) has largely given up on it? One day in 1757 the poet Christopher Smart went out to St James’s Park, started praying loudly and couldn’t stop. He was hauled off to St Luke’s Asylum, where a cascade of ecstatic verse proceeded to pour from him, in which he identified his cat companion, Jeoffry, as ‘the servant of the Living God’. According to Smart’s delighted itemising, Jeoffry served the Almighty by catching rats, keeping his front paws pernickety clean and observing the watches of the night. He was a peaceable soul too, kissing neighbouring cats ‘in kindness’ and letting a mouse escape one time in seven. But perhaps Jeoffry’s greatest accomplishment was his ability to ‘spraggle upon waggle’. Both spraggling and waggling, Smart’s magnificat suggests, are deeply pleasing to the Lord.

One day in 1757 the poet Christopher Smart went out to St James’s Park, started praying loudly and couldn’t stop. He was hauled off to St Luke’s Asylum, where a cascade of ecstatic verse proceeded to pour from him, in which he identified his cat companion, Jeoffry, as ‘the servant of the Living God’. According to Smart’s delighted itemising, Jeoffry served the Almighty by catching rats, keeping his front paws pernickety clean and observing the watches of the night. He was a peaceable soul too, kissing neighbouring cats ‘in kindness’ and letting a mouse escape one time in seven. But perhaps Jeoffry’s greatest accomplishment was his ability to ‘spraggle upon waggle’. Both spraggling and waggling, Smart’s magnificat suggests, are deeply pleasing to the Lord.