Sughra Raza. Island Pond Algae, Upstate NY. July 26, 2020.

Sughra Raza. Island Pond Algae, Upstate NY. July 26, 2020.

Digital photograph.

Sughra Raza. Island Pond Algae, Upstate NY. July 26, 2020.

Sughra Raza. Island Pond Algae, Upstate NY. July 26, 2020.

Digital photograph.

by Sabyn Javeri Jillani

‘To be a woman is to be an actress’, writes Susan Sontag in her 1972 essay The Double Standards of Ageing. She is referring to the beauty norms that expect women to freeze ageing while levying no such expectations on men. As the popular saying goes, men become wiser with age while women become older; men being judged by their maturity while women through their bodies. Beauty is often associated with the young and so these pressures of eternal youth trap our subconscious in unrealistic standards of attractiveness. Performing to a biased audience, women become objects of their own calling for as Sontag writes, ‘From early childhood on, girls are trained to care in a pathologically exaggerated way about their appearance’. She wrote this nearly 50 years ago. Since then, there has been a lot of consciousness-raising debates about these reductive attitudes, and nowadays you would be hard pressed to find someone who would admit to the pressures of ‘youthful preservation’. They call it ‘selfcare’, instead. But is it really?

I’ve always been suspicious of dressing up to please others but I’m even more skeptical of dressing up for myself. Despite all the consciousness-raising feminist movements that made us aware of women’s history of objectification, the fact remains that prior to the pandemic many of us still spent a lot of time and money on beautifying ourselves according to societal standards. Only this time the capitalists were selling it to us as ‘selfcare’ and ‘wellbeing’. The pandemic has made us rethink how beauty and youth have been rebranded as ‘selfcare’ while still pandering to the imaginary audience that makes being a woman a performance. Much along the lines of Sheryl Sandberg’s neoliberal ‘Lean in’ feminism which tells women to take responsibility for their marginalization, the new beauty standards tell us to look good ‘for ourselves’. In other words, looking good is for our own good. Read more »

by Paul Orlando

I’ve been exploring ways that tech innovation could lead to inevitable outcomes. Here’s a continuation of that, specific to the enduring human need for music.

Music has been around as long as there have been people. Longer if you count music made by animals. It’s safe to say that music will be a part of this world as long as there is life. So what happens when new technology encounters an eternal constant for humans?

Demand for something like music is built into what it means to be human. Music related tech development (especially if it is more about improvements rather than step changes) can be somewhat predictable. I use the term inevitable because we’re combining enduring human needs with forces that are largely about laws of physics applied to manufacturing. Supporting business models form.

Let’s look at some of the changes over the 20th century of the music industry. Treat this as a thought experiment on applying second-order thinking.

If you were born in 1900, in the early years of the recording industry, it’s likely that all of the music you heard growing up would be live music. An informal local band, or a more formal chamber orchestra, or singing in the home. You also would have been a child when Enrico Caruso recorded these versions of “Vesti la Giubba,” from the opera Pagliacci (which premiered in 1892).

Enrico Caruso – Vesti la Giubbia, first decade of 1900s

Caruso was one of the first international stars, both because he was a great tenor and also because his career coincided with the development of the early recording industry. His combined “Vesti la Giubba,” recordings are counted as the first million unit record sale in the US. (A bigger deal back then with one-quarter of today’s population and less disposable income.) Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Anitra Pavlico

As we wait for life in this era to regain a sense of normalcy and rationality, we take refuge in other eras. There is a severe shortage of contemporary human activities–art-making, conversation, building things. The past becomes closer and larger. The future has shrunk and become clouded, even dark. We have nowhere to go but back, but the past is likewise little comfort, partly because five months ago feels like five decades ago–quaint, old-fashioned, hopelessly out of touch.

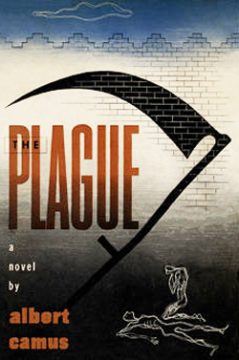

The themes of time, memory, and collective humanity in Albert Camus’s The Plague have preoccupied me lately. The Algerian town of Oran is cut off from the rest of the world in an attempt to contain the pestilence that has taken hold there.

But the plague forced inactivity on them, limiting their movements to the same dull round inside the town, and throwing them, day after that, on the illusive solace of their memories. . . . they drifted through life rather than lived, the prey of aimless days and sterile memories, like wandering shadows that could have acquired substance only by consenting to root themselves in the solid earth of their distress.

It is difficult to tell whether time for us has slowed to a near-stop or has sped up. We have less variety in our days, and yet there are times when the hours race by and we haven’t accomplished a fraction of what we set out to do that day. It is more likely that we have slowed down, dulled by inaction to insipidity, than that time has accelerated, but the result is the same: nothing results. As Camus writes: Those who had jobs went about them at the exact tempo of the plague, with dreary perseverance. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

In high school, I attended a “debate camp” at a small university in southeastern Missouri. I was thrilled to visit my first college bookstore while there and I bought a cheap, slender volume out of the remainders bin called “Parables and Paradoxes”. It was written by Franz Kafka. I am embarrassed to say that I recognized the name only because I was a big fan of the stories of Jorge Luis Borges and he mentioned Kafka here and there. In one essay, for example, Borges used Kafka to illustrate how great writers rewrite the works of their own precursors. Surveying a disparate collection of works, Borges says that “Kafka’s idiosyncrasy is present in each of these writings, to a greater or lesser degree, but if Kafka had not written, we would not perceive it; that is to say, it would not exist.”

The difference between Kafka and Borges that struck me almost immediately was that despite the labyrinthine, elliptical, and self-referential character of Borges’ stories it always seemed more or less clear to me what they meant; whereas Kafka’s stories seemed clearly to mean something, but it was never clear to me exactly what. What is the meaning of that hideous machine that writes on human flesh, the secret trial where Joseph K. is never charged but loses his life, of Gregor Samson transformed into a gigantic bug? The very elusiveness of meaning in Kafka intensifies the search for it.

It’s not just me. Psychologists asked subjects to read either “The Country Dentist” by Kafka or a rewritten version that changed all the weird, unexplained bits. Subjects who read the Kafka story were better able to spot hidden patterns in rows of letters afterwards than those who read the “normalized” version. The experimenters theorize that encountering the unexpected can increase people’s ability to creatively search for meaning. They call it “The Kafka Effect”. Read more »

by Adele Wilby

Nothing focuses minds like grave events that bring about severe disruption to everyday living. Over recent times, two major happenings, one with global and the other with more regional implications, have jolted people out of their complacency and compelled some reflection on unpredictability and uncertainty in life, and what is going on around us.

Nothing focuses minds like grave events that bring about severe disruption to everyday living. Over recent times, two major happenings, one with global and the other with more regional implications, have jolted people out of their complacency and compelled some reflection on unpredictability and uncertainty in life, and what is going on around us.

Firstly, the coronavirus pandemic has concentrated governments and the people throughout the world on measures to control this previously unknown deadly virus that has taken the lives of hundreds of thousands of people and infected more than double that amount in the process. The ‘lockdown’ of entire populations in a bid to starve the virus of hosts for its reproduction has been the key strategy adopted by many governments in dealing with this lethal viral infection. People have stayed at home, ‘lock-downed’, and travelling has been brought to a halt. ‘High’ and ‘low’ and all those in between have had to garner themselves for tough times behind closed doors, cutting themselves off from loved ones and friends as the most effective strategy of containment of the lethal potential of this minute protein invisible to the human eye.

The second issue that has jolted the thinking of many people across the globe, particularly the western liberal world, stems from the recent murder of an innocent black man, George Floyd, by the police in Minneapolis, in the United States (US). The video of this man being viciously and callously murdered by a white police officer as he pleaded for his breath has appeared in all forms of social media throughout the world, sparking widespread abhorrence, condemnation, anger, and for many, utter rage. The image of the US as a liberal, just society with solid institutions based on equality and fairness has been shaken, perhaps irreparably shattered. Tragically, this is not the first incident of police officers killing black men in the US, but it is an incident that proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back and set off widespread protests across the US and in many other countries in sympathy and solidarity with the US protestors. The murder and subsequent protests have placed racism more generally and institutionalised racism in the United States once again to the fore, elevating it to one of the hottest topics in US politics today. Read more »

by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

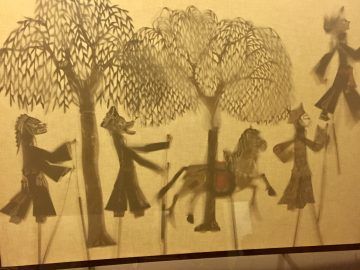

When the Rajah’s barber could no longer keep the secret, he was seen darting by the sparrow in the tamarind, by the flinty owl in the giant oak that was surely a jinn’s abode, by a flock of hill mynahs flying through the buttery light of early spring. What was it that sent him bumbling through the jungle like that? Hours before, he had met the Rajah’s terrible gaze in the mirror when he discovered two sickle-shaped horns under his hair. This secret was as a rock he had swallowed, a rock he needed to expel. He was found panting by the fox of the jungle’s dank center, by a tightly knotted vine clutching a forgotten well. He saw that the well was old and there was bamboo growing in it. He saw it was safe and he screamed his fullest scream into the well: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret and happily soaked it up, but the next day it was cut down by a flute maker who had been in search of just the right bamboo. Soon, all his fine bamboo flutes were sold. Then, all the new flutes of Jaunpur sang out the secret: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret. The hapless barber had poured into it his last song.

When the Rajah’s barber could no longer keep the secret, he was seen darting by the sparrow in the tamarind, by the flinty owl in the giant oak that was surely a jinn’s abode, by a flock of hill mynahs flying through the buttery light of early spring. What was it that sent him bumbling through the jungle like that? Hours before, he had met the Rajah’s terrible gaze in the mirror when he discovered two sickle-shaped horns under his hair. This secret was as a rock he had swallowed, a rock he needed to expel. He was found panting by the fox of the jungle’s dank center, by a tightly knotted vine clutching a forgotten well. He saw that the well was old and there was bamboo growing in it. He saw it was safe and he screamed his fullest scream into the well: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret and happily soaked it up, but the next day it was cut down by a flute maker who had been in search of just the right bamboo. Soon, all his fine bamboo flutes were sold. Then, all the new flutes of Jaunpur sang out the secret: “the-Rajah-has-horns-on-his-head!” The bamboo had been thirsty for a secret. The hapless barber had poured into it his last song.

***

Note: This is my retelling of a favorite Urdu story from childhood. Many stories like this one are set in Jaunpur in North India, not far from Lucknow. Named after Jauna Khan, Jaunpur was known in the medieval times as a hub of Sufi culture. This story likely has roots in the Persian tradition. “Dhul Qarnain” or the “two-horned one” is a figure from the Quran, said to refer to Alexander the Great whose depictions in art, literature and folklore have been part of the Silk Road’s syncretic cultures for centuries.

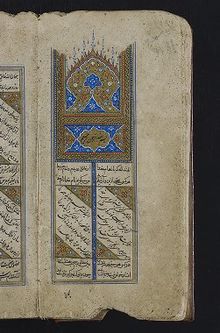

by Claire Chambers

Ghazal poetry is an intimate and relatively short lyric form of verse from the Middle East and South Asia. The form thrives in such languages as Arabic, Persian, Urdu, and now English. Like the Western ode, these poems are often addressed to a love object. Influenced by ecstatic Sufi Islam, the ghazal’s subject matter concerns desire for another person and, figuratively, love for the Divine.

Indeed, a mixture of sacred, profane, romantic, and melancholic elements are frequently stitched into the ghazal’s poetic fabric. Many ghazals revolve around the theme of lovers’ separation. This topic also functions as an image for the Muslim worshipper’s longing for Allah. In doing so, the ghazal draws comparisons with seventeenth-century metaphysical poetry. Like ghazalists, John Donne would ostensibly write about love for a woman but also shadow forth devotion to God.

Sound, rhyme, repetition, and rhythm come to the forefront in this form. This makes it unsurprising that many ghazals have been turned into songs. For instance, during the course of his illustrious poetic career, Mohammad (‘Allama’) Iqbal (1877–1938) wrote dozens of ghazals. Some of these poems have been set to music. They were sung by popular South Asian musicians including the late Mehdi Hassan and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, as well as contemporary singers Lata Mangeshkar and Sanam Marvi. I also think of the famous playback singers Noor Jehan’s and Nayyara Noor’s renditions of the poetry of Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911–1984). This crossover often surprises Westerners: it’s as though Carol Ann Duffy’s poems were being sung by Rihanna! Read more »

Steven Levy in Wired:

FOR 20 YEARS, Bill Gates has been easing out of the roles that made him rich and famous—CEO, chief software architect, and chair of Microsoft—and devoting his brainpower and passion to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, abandoning earnings calls and antitrust hearings for the metrics of disease eradication and carbon reduction. This year, after he left the Microsoft board, one would have thought he would have relished shedding the spotlight directed at the four CEOs of big tech companies called before Congress.

FOR 20 YEARS, Bill Gates has been easing out of the roles that made him rich and famous—CEO, chief software architect, and chair of Microsoft—and devoting his brainpower and passion to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, abandoning earnings calls and antitrust hearings for the metrics of disease eradication and carbon reduction. This year, after he left the Microsoft board, one would have thought he would have relished shedding the spotlight directed at the four CEOs of big tech companies called before Congress.

But as with many of us, 2020 had different plans for Gates. An early Cassandra who warned of our lack of preparedness for a global pandemic, he became one of the most credible figures as his foundation made huge investments in vaccines, treatments, and testing. He also became a target of the plague of misinformation afoot in the land, as logorrheic critics accused him of planning to inject microchips in vaccine recipients. (Fact check: false. In case you were wondering.)

WIRED: You have been warning us about a global pandemic for years. Now that it has happened just as you predicted, are you disappointed with the performance of the United States?

Bill Gates: Yeah. There’s three time periods, all of which have disappointments. There is 2015 until this particular pandemic hit. If we had built up the diagnostic, therapeutic, and vaccine platforms, and if we’d done the simulations to understand what the key steps were, we’d be dramatically better off. Then there’s the time period of the first few months of the pandemic, when the US actually made it harder for the commercial testing companies to get their tests approved, the CDC had this very low volume test that didn’t work at first, and they weren’t letting people test. The travel ban came too late, and it was too narrow to do anything. Then, after the first few months, eventually we figured out about masks, and that leadership is important.

More here.

Ed Yong in The Atlantic:

There’s a joke about immunology, which Jessica Metcalf of Princeton recently told me. An immunologist and a cardiologist are kidnapped. The kidnappers threaten to shoot one of them, but promise to spare whoever has made the greater contribution to humanity. The cardiologist says, “Well, I’ve identified drugs that have saved the lives of millions of people.” Impressed, the kidnappers turn to the immunologist. “What have you done?” they ask. The immunologist says, “The thing is, the immune system is very complicated …” And the cardiologist says, “Just shoot me now.”

There’s a joke about immunology, which Jessica Metcalf of Princeton recently told me. An immunologist and a cardiologist are kidnapped. The kidnappers threaten to shoot one of them, but promise to spare whoever has made the greater contribution to humanity. The cardiologist says, “Well, I’ve identified drugs that have saved the lives of millions of people.” Impressed, the kidnappers turn to the immunologist. “What have you done?” they ask. The immunologist says, “The thing is, the immune system is very complicated …” And the cardiologist says, “Just shoot me now.”

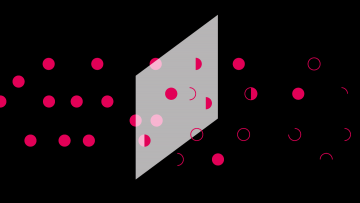

The thing is, the immune system is very complicated. Arguably the most complex part of the human body outside the brain, it’s an absurdly intricate network of cells and molecules that protect us from dangerous viruses and other microbes. These components summon, amplify, rile, calm, and transform one another: Picture a thousand Rube Goldberg machines, some of which are aggressively smashing things to pieces. Now imagine that their components are labeled with what looks like a string of highly secure passwords: CD8+, IL-1β, IFN-γ. Immunology confuses even biology professors who aren’t immunologists—hence Metcalf’s joke.

More here.

Laleh Khalili in The Guardian:

While attention and anger has focused on the incompetence and dysfunction of the Lebanese government and authorities, the roots of the catastrophe run far deeper and wider – to a network of maritime capital and legal chicanery that is designed to protect businesses at any cost.

While attention and anger has focused on the incompetence and dysfunction of the Lebanese government and authorities, the roots of the catastrophe run far deeper and wider – to a network of maritime capital and legal chicanery that is designed to protect businesses at any cost.

Whatever sparked the initial fire, the secondary explosion that destroyed the port and so much of the city was caused by 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate stored in a port warehouse. A chemical used in both agriculture and construction, ammonium nitrate is associated with the 1993 Bishopsgate bombing in London and the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995. It was also the cause of huge explosions in Galveston, Texas in 1947 and Tianjin port in China in 2015, both of which killed scores of people. How did such a dangerous incendiary end up in a warehouse so close to residential areas of Beirut?

In September 2013, the cargo vessel the MV Rhosus – owned by a Russian, registered to a company in Bulgaria and flagged to Moldova – set sail from Batumi in Georgia to Mozambique.

More here.

Leigh Phillips in Jacobin:

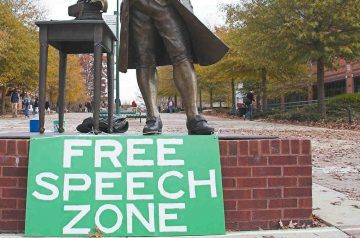

In recent years, there has been a marked and disquieting increase in the willingness of a raft of actors left, center, and right, both in government and in civil society, to engage in a practice and attitude of censorship and to abandon due process, presumption of innocence, and other core civil liberties.

In recent years, there has been a marked and disquieting increase in the willingness of a raft of actors left, center, and right, both in government and in civil society, to engage in a practice and attitude of censorship and to abandon due process, presumption of innocence, and other core civil liberties.

There have been some attempts from different quarters at a pushback against this, but the most recent such effort at a course correction is an open letter decrying the phenomenon appearing in Harper’s magazine. The letter, signed by some 150 public intellectuals, writers, and academics including figures like Noam Chomsky, Margaret Atwood, and Salman Rushdie, has provoked a polarizing response.

Current Affairs editor Nathan Robinson, for example, argues that all this is a right-wing myth, slander against the Left, that those perpetrating the alleged acts of censorship are in fact relatively powerless, and that when incidents of alleged “cancel-culture censorship” are investigated, one finds that the targets are doing just fine after all.

Because the Harper’s letter was fairly anodyne and declined to mention any specific incidents, Robinson cherry-picks a small sample of occurrences that he imagines must be what the signatories are talking about and tries to demonstrate that these incidents were really nothing-burgers of no consequence, distracting us from real issues.

More here.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jgj6jScPWK8

Eva Botkin-Kowacki in The Christian Science Monitor:

To some witnesses, it simply didn’t make sense. “This is really an irrational phenomenon,” wrote the Polish historian Emanuel Ringelblum, in notes found after his execution by the Gestapo. “There’s no explaining it rationally.” It was November 1941 in the Warsaw Ghetto, the sliver of Poland’s capital that the Nazi occupying government had transformed into a squalid holding pen for the area’s Jews, Romani, and others deemed undesirable. Typhus had raged through the community all through the summer and early autumn. But then, just as infection rates were expected to have skyrocketed as winter approached, cases fell dramatically. “I heard this from the apothecaries, and the same thing from doctors and the hospital,” Ringelblum wrote that month. “The epidemic rate has fallen some 40 per cent.”

To some witnesses, it simply didn’t make sense. “This is really an irrational phenomenon,” wrote the Polish historian Emanuel Ringelblum, in notes found after his execution by the Gestapo. “There’s no explaining it rationally.” It was November 1941 in the Warsaw Ghetto, the sliver of Poland’s capital that the Nazi occupying government had transformed into a squalid holding pen for the area’s Jews, Romani, and others deemed undesirable. Typhus had raged through the community all through the summer and early autumn. But then, just as infection rates were expected to have skyrocketed as winter approached, cases fell dramatically. “I heard this from the apothecaries, and the same thing from doctors and the hospital,” Ringelblum wrote that month. “The epidemic rate has fallen some 40 per cent.”

The Warsaw Ghetto should have been an optimal site for an outbreak. More than 450,000 mostly Jewish inmates were crammed into 1.3 square miles, making for a population density between 5 and 10 times that of today’s busiest cities. Nazi authorities deliberately kept resources from entering the area, all the while using fear of disease in anti-Semitic party propaganda. Nevertheless, typhus rates in the Warsaw Ghetto were plummeting.

The only explanation, according to research published today in the journal Science Advances, is that the inmates did it themselves, by sheltering in place, promoting and enforcing hygiene, and practicing social distancing. This remarkable story of an oppressed community rallying together to combat a public health crisis holds obvious implications for today, as the novel coronavirus pandemic continues to claim thousands of lives around the world daily and debilitate national economies. “It’s one of the great medical stories of all time,” says Howard Markel, the University of Michigan physician and medical historian who coined the term “flatten the curve” in relation to COVID-19. “We should take heart and inspiration from the courage, bravery, and unity of doctors, nurses, and patients alike to combat an infectious foe. We need to do that today, and they did it under much more dire circumstances.”

More here.

Laura Marris in The New York Times:

“The Plague” did not come easily to Camus. He wrote it in Oran, during World War II, when he was living in an apartment borrowed from in-laws he disliked, and then in wartime France, tubercular and alone, separated from his wife after missing the last boat back to Algeria. Unlike the shorter, harsher sentences of “The Stranger,” which Sartre quipped could have been titled “Translated From Silence,” the sentences of “The Plague” bear witness to the tension and monotony of illness and quarantine: They stretch their lengths to match the pull of anxious waiting. By the time the book was published in 1947, writers were looking for a way to bear witness as well to the Nazi occupation of France, and “The Plague” was championed as the novel of the occupation and the Resistance. For Camus, illness was both his lived experience and a metaphor for war, the creep of fascism, the horror of Vichy France collaborating in mass murder.

“The Plague” did not come easily to Camus. He wrote it in Oran, during World War II, when he was living in an apartment borrowed from in-laws he disliked, and then in wartime France, tubercular and alone, separated from his wife after missing the last boat back to Algeria. Unlike the shorter, harsher sentences of “The Stranger,” which Sartre quipped could have been titled “Translated From Silence,” the sentences of “The Plague” bear witness to the tension and monotony of illness and quarantine: They stretch their lengths to match the pull of anxious waiting. By the time the book was published in 1947, writers were looking for a way to bear witness as well to the Nazi occupation of France, and “The Plague” was championed as the novel of the occupation and the Resistance. For Camus, illness was both his lived experience and a metaphor for war, the creep of fascism, the horror of Vichy France collaborating in mass murder.

But unlike many of his contemporaries, Camus took the long view. The heroism of the Resistance was less important to him than how humanity could be restored after the war. In his speech “The Human Crisis,” delivered at Columbia University in 1946, he pushed for a postwar return to the human scale, calling hatred and indifference “symptoms” of this crisis. He refused to let his country off the hook for its role in spreading this illness: “And it’s too easy, on this point, simply to accuse Hitler and say that the snake has been destroyed, the venom gone. Because we know perfectly well that the venom is not gone, that each of us carries it in our own hearts.”

While he knew that people carried traces of hatred, he was also hoping those traces could be disarmed as cultural antibodies. In this same speech, he called for creating “communities of thought outside parties and governments to launch a dialogue across national boundaries; the members of these communities will affirm by their lives and their words that this world must cease to be the world of police, soldiers and money, and become the world of men and women, of fruitful work and thoughtful play.”

More here.

Almost all the statuaries were killers

if on horseback, add ten thousand

to the toll. And sword-bearers?

Notch another zero. We think

we worship life, but we have

made a botch of this, encircling

ponds and trees with the smelt

of disused weapons, planting flowers

around the ankles of killers,

even the birds know not to use them

as lighthouses. Death

is our archangel, our leaders

bronze themselves in advance—

even a dog can’t trot through the palace

halls these days without looking over

its shoulder.

by John Freeman

from The Park

Copper Canyon Press, 2020