Megan Scudellari in Nature:

To end the pandemic, the virus must either be eliminated worldwide — which most scientists agree is near-impossible because of how widespread it has become — or people must build up sufficient immunity through infections or a vaccine. It is estimated that 55–80% of a population must be immune for this to happen, depending on the country11.

To end the pandemic, the virus must either be eliminated worldwide — which most scientists agree is near-impossible because of how widespread it has become — or people must build up sufficient immunity through infections or a vaccine. It is estimated that 55–80% of a population must be immune for this to happen, depending on the country11.

Unfortunately, early surveys suggest there is a long way to go. Estimates from antibody testing — which reveals whether someone has been exposed to the virus and made antibodies against it — indicate that only a small proportion of people have been infected, and disease modelling backs this up. A study of 11 European countries calculated an infection rate of 3–4% up to 4 May12, inferred from data on the ratio of infections to deaths, and how many deaths there had been. In the United States, where there have been more than 150,000 COVID-19 deaths, a survey of thousands of serum samples, coordinated by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, found that antibody prevalence ranged from 1% to 6.9%, depending on the location13.

…It’s unlikely that there will never be a vaccine, given the sheer amount of effort and money pouring into the field and the fact that some candidates are already being tested in humans, says Velasco-Hernández. The World Health Organization lists 26 COVID-19 vaccines currently in human trials, with 12 of them in phase II trials and six in phase III. Even a vaccine providing incomplete protection would help by reducing the severity of the disease and preventing hospitalization, says Wu. Still, it will take months to make and distribute a successful vaccine.

More here.

In the mid-2010s, a curious new vocabulary began to unspool itself in our media. A data site,

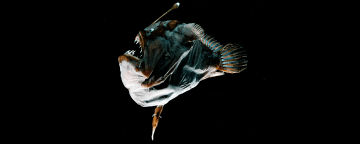

In the mid-2010s, a curious new vocabulary began to unspool itself in our media. A data site,  Most animals that change color to match their surroundings can see what these surroundings look like. But the peppered moth caterpillar can do this with its eyes closed, according to a new study, and scientists have figured out how.

Most animals that change color to match their surroundings can see what these surroundings look like. But the peppered moth caterpillar can do this with its eyes closed, according to a new study, and scientists have figured out how. Kashmir’s new Domicile Law is a cognate of India’s new blatantly anti-Muslim Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) passed in December 2019 and the National Register of Citizens (NRC) that is supposed to detect ‘Bangladeshi infiltrators’ (Muslim of course) who the home minister has called ‘termites’. In the state of Assam, the NRC has already wreaked havoc. Millions have been struck off the citizens register. While many countries are dealing with a refugee crisis, the Indian government is turning citizens into refugees, fuelling a crisis of statelessness on an unimaginable scale.

Kashmir’s new Domicile Law is a cognate of India’s new blatantly anti-Muslim Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) passed in December 2019 and the National Register of Citizens (NRC) that is supposed to detect ‘Bangladeshi infiltrators’ (Muslim of course) who the home minister has called ‘termites’. In the state of Assam, the NRC has already wreaked havoc. Millions have been struck off the citizens register. While many countries are dealing with a refugee crisis, the Indian government is turning citizens into refugees, fuelling a crisis of statelessness on an unimaginable scale. We also fall in love again with the irreverent, brilliant Kahlo, who is both charming and insolent in every anecdote. She feels Breton’s accommodations and manners are beneath her and ends up sexually entangled with his wife, Jacqueline Lamba (Breton gets to watch). And there is much delight to be had in Kahlo’s repeatedly expressing her disdain for French culture, especially its artistic circles. “I [would] rather sit on the floor in the market of Toluca and sell tortillas, than to have anything to do with those ‘artistic’ bitches of Paris.” (Bitches seems to be her favorite word for Parisians!) Indeed, the French seem to misunderstand her; the poet Robert Desnos says to Petitjean’s father at one point, “Your friend’s pretty, she could have stepped right out of a display at your Museum of Ethnography.” But we are assured Petitjean is “more attracted to her personality and her culture than her exotic ‘ethnic’ appearance.” In normal circumstances, this would seem shaky, but given the character of Michel, we buy it. Both Petitjeans gain our trust so fully that we don’t question their Occidentalist magnanimity at certain awkward points; while France and the French are belittled by our French author, Kahlo’s Mexico is championed as a center for the arts.

We also fall in love again with the irreverent, brilliant Kahlo, who is both charming and insolent in every anecdote. She feels Breton’s accommodations and manners are beneath her and ends up sexually entangled with his wife, Jacqueline Lamba (Breton gets to watch). And there is much delight to be had in Kahlo’s repeatedly expressing her disdain for French culture, especially its artistic circles. “I [would] rather sit on the floor in the market of Toluca and sell tortillas, than to have anything to do with those ‘artistic’ bitches of Paris.” (Bitches seems to be her favorite word for Parisians!) Indeed, the French seem to misunderstand her; the poet Robert Desnos says to Petitjean’s father at one point, “Your friend’s pretty, she could have stepped right out of a display at your Museum of Ethnography.” But we are assured Petitjean is “more attracted to her personality and her culture than her exotic ‘ethnic’ appearance.” In normal circumstances, this would seem shaky, but given the character of Michel, we buy it. Both Petitjeans gain our trust so fully that we don’t question their Occidentalist magnanimity at certain awkward points; while France and the French are belittled by our French author, Kahlo’s Mexico is championed as a center for the arts. No Room at the Morgue and its sequel, Que d’os!, are the only two of Manchette’s novels to feature a private eye as protagonist. Though in Manchette there’s never a shortage of killers for hire, killers for the hell of it, casual psychotics, mercenaries, and the corruption of each and every institution, there are relatively few police in his policiers, and very little mystery about the who in whodunit. The Tarpon novels are in some sense a throwback to a time when the genre was more tightly defined, its tropes less problematic. We’ve got a down-at-heels PI here, and bad guys, and a femme-more-or-less-fatale, and a couple of cops either of whom could be played by Lino Ventura. But Manchette certainly isn’t slumming, or doing a genre turn to please his fans. As Manchette asks, “What do you do when you re-do [the classic American crime novels] at a distance—distant because the moment of that something is long gone? The American-style polar had its day. Writing in 1970 meant taking a new social reality into account, but it also meant acknowledging that the polar-form was finished because its time was finished: re-employing an obsolete form implies employing it referentially, honoring it by criticizing it, exaggerating it, distorting it from top to bottom.” Or as he put it more bluntly (and more flamboyantly): “The overtures of the ‘neo-detective novel’ have been progressively conquered by literary hacks (of Art) or by Gorbachev-loving Stalino Trotskyist racketeers.”

No Room at the Morgue and its sequel, Que d’os!, are the only two of Manchette’s novels to feature a private eye as protagonist. Though in Manchette there’s never a shortage of killers for hire, killers for the hell of it, casual psychotics, mercenaries, and the corruption of each and every institution, there are relatively few police in his policiers, and very little mystery about the who in whodunit. The Tarpon novels are in some sense a throwback to a time when the genre was more tightly defined, its tropes less problematic. We’ve got a down-at-heels PI here, and bad guys, and a femme-more-or-less-fatale, and a couple of cops either of whom could be played by Lino Ventura. But Manchette certainly isn’t slumming, or doing a genre turn to please his fans. As Manchette asks, “What do you do when you re-do [the classic American crime novels] at a distance—distant because the moment of that something is long gone? The American-style polar had its day. Writing in 1970 meant taking a new social reality into account, but it also meant acknowledging that the polar-form was finished because its time was finished: re-employing an obsolete form implies employing it referentially, honoring it by criticizing it, exaggerating it, distorting it from top to bottom.” Or as he put it more bluntly (and more flamboyantly): “The overtures of the ‘neo-detective novel’ have been progressively conquered by literary hacks (of Art) or by Gorbachev-loving Stalino Trotskyist racketeers.” The population of bacteria in the pancreas increases more than a thousand fold in patients with pancreatic cancer, and becomes dominated by species that prevent the immune system from attacking tumor cells. These are the findings of a study conducted in mice and in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA), a form of cancer that is usually fatal within two years.

The population of bacteria in the pancreas increases more than a thousand fold in patients with pancreatic cancer, and becomes dominated by species that prevent the immune system from attacking tumor cells. These are the findings of a study conducted in mice and in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA), a form of cancer that is usually fatal within two years. Donald Trump was headed to historic Jamestown to mark the 400th anniversary of the first representative assembly of European settlers in the Americas. But Black Virginia legislators were boycotting the visit. Over the preceding two weeks, the president had been engaged in one of the most racist political assaults on members of Congress in American history. Like so many controversies during Trump’s presidency, it had all started with an early-morning tweet. “So interesting to see ‘Progressive’ Democrat Congresswomen, who originally came from countries whose governments are a complete and total catastrophe, the worst, most corrupt and inept anywhere in the world (if they even have a functioning government at all), now loudly and viciously telling the people of the United States, the greatest and most powerful Nation on earth, how our government is to be run,” Trump tweeted on Sunday, July 14, 2019. “Why don’t they go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came. Then come back and show us how it is done. These places need your help badly, you can’t leave fast enough.”

Donald Trump was headed to historic Jamestown to mark the 400th anniversary of the first representative assembly of European settlers in the Americas. But Black Virginia legislators were boycotting the visit. Over the preceding two weeks, the president had been engaged in one of the most racist political assaults on members of Congress in American history. Like so many controversies during Trump’s presidency, it had all started with an early-morning tweet. “So interesting to see ‘Progressive’ Democrat Congresswomen, who originally came from countries whose governments are a complete and total catastrophe, the worst, most corrupt and inept anywhere in the world (if they even have a functioning government at all), now loudly and viciously telling the people of the United States, the greatest and most powerful Nation on earth, how our government is to be run,” Trump tweeted on Sunday, July 14, 2019. “Why don’t they go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came. Then come back and show us how it is done. These places need your help badly, you can’t leave fast enough.” “Forward! Brave people! The goddess of liberty leads you on!” So declares Count Egmont, the protagonist in Goethe’s exquisite 1788 play, Egmont, a tragedy based on the Dutch revolt of the late 16th century. “And as the sea breaks through and destroys the barriers that would oppose its fury, so do ye overwhelm the bulwark of tyranny, and with your impetuous flood sweep it away from the land which it usurps.”

“Forward! Brave people! The goddess of liberty leads you on!” So declares Count Egmont, the protagonist in Goethe’s exquisite 1788 play, Egmont, a tragedy based on the Dutch revolt of the late 16th century. “And as the sea breaks through and destroys the barriers that would oppose its fury, so do ye overwhelm the bulwark of tyranny, and with your impetuous flood sweep it away from the land which it usurps.” When I was 19, in the summer of 1995, I fell in love with an owl. I’d just spent two weeks in Primorye in the Russian far east – a wild, mountainous province bordering the Sea of Japan, China and North Korea. It is a region of dense forests, rolling mountains, clean rivers and spectacular coastlines. Exotic locations were nothing new for me: I was born in the United States but grew up in a diplomat’s family, bouncing around the world from Uruguay to Panama as a young child, and to West Germany and Canada as a teen. Before the age of 16, I’d only lived in the United States for two years.

When I was 19, in the summer of 1995, I fell in love with an owl. I’d just spent two weeks in Primorye in the Russian far east – a wild, mountainous province bordering the Sea of Japan, China and North Korea. It is a region of dense forests, rolling mountains, clean rivers and spectacular coastlines. Exotic locations were nothing new for me: I was born in the United States but grew up in a diplomat’s family, bouncing around the world from Uruguay to Panama as a young child, and to West Germany and Canada as a teen. Before the age of 16, I’d only lived in the United States for two years. Thomas Frank is one of America’s more skillful writers, an expert practitioner of a genre one might call historical journalism – ironic, because no recent media figure has been more negatively affected by historical change. Frank became a star during a time of intense curiosity about the reasons behind our worsening culture war, and now publishes a terrific book, The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism, at a time when people are mostly done thinking about what divides us, gearing up to fight instead.

Thomas Frank is one of America’s more skillful writers, an expert practitioner of a genre one might call historical journalism – ironic, because no recent media figure has been more negatively affected by historical change. Frank became a star during a time of intense curiosity about the reasons behind our worsening culture war, and now publishes a terrific book, The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism, at a time when people are mostly done thinking about what divides us, gearing up to fight instead. In Khalidi’s latest book, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, history proves once again to be the key to understanding the present. He builds on his previous work, interspersing personal and family stories with political ones and tracing the lineage of violence that has engulfed a land that has been known by many different names. In doing so, Khalidi identifies many of the actors who have been instrumental to the Palestinian cause, the revolutionaries, women, and young people who helped build the fabric of Palestinian life within the shadow of endless war, displacement, and occupation.

In Khalidi’s latest book, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, history proves once again to be the key to understanding the present. He builds on his previous work, interspersing personal and family stories with political ones and tracing the lineage of violence that has engulfed a land that has been known by many different names. In doing so, Khalidi identifies many of the actors who have been instrumental to the Palestinian cause, the revolutionaries, women, and young people who helped build the fabric of Palestinian life within the shadow of endless war, displacement, and occupation. My favorite versions of Dylan are the two I like to think of as Romantic Bob and Contemptuous Dylan. The former is the most lovable of love-song writers, the latter the cool guy who scorns his fans. They came together best in the classics of the 1970s that are now rather unfashionable among Dylan obsessives, especially Blood on the Tracks (1975) and its outtakes recently released as More Blood, More Tracks: Bootleg Series Vol. 14 (2018). “Any fool could find whatever he wanted inside the vast Dylan songbook: drugs, Jesus, Joan Baez,” David Kinney wrote in The Dylanologists. It’s impossible to disagree, but I’ve always foolishly enjoyed the search for the traces of “real” women in Dylan’s life. There are the wistful, bittersweet Suze Rotolo songs of the 1960s; the stories of his first marriage and divorce to Sara Dylan (who is the presumed inspiration of one of his greatest love songs, “Abandoned Love,” an outtake off Desire (1976)); the tortured ballads of the 1990s (which of them are odes to Mavis Staples?); and the special sentimentality seemingly reserved for Baez: “We could sing together in our sleep,” Dylan says of her in Scorsese’s Rolling Thunder Revue (2019). She seemed to remember things a little differently in “Diamonds and Rust” (1975): “My poetry was lousy, you said.“ A man I once loved used to tease me for my clichéd preoccupations with Dylan’s most mawkish of songs about bad love, “Idiot Wind,” but its portrayal of cruelty and masochism is also Dylan at his most usable for feminists.

My favorite versions of Dylan are the two I like to think of as Romantic Bob and Contemptuous Dylan. The former is the most lovable of love-song writers, the latter the cool guy who scorns his fans. They came together best in the classics of the 1970s that are now rather unfashionable among Dylan obsessives, especially Blood on the Tracks (1975) and its outtakes recently released as More Blood, More Tracks: Bootleg Series Vol. 14 (2018). “Any fool could find whatever he wanted inside the vast Dylan songbook: drugs, Jesus, Joan Baez,” David Kinney wrote in The Dylanologists. It’s impossible to disagree, but I’ve always foolishly enjoyed the search for the traces of “real” women in Dylan’s life. There are the wistful, bittersweet Suze Rotolo songs of the 1960s; the stories of his first marriage and divorce to Sara Dylan (who is the presumed inspiration of one of his greatest love songs, “Abandoned Love,” an outtake off Desire (1976)); the tortured ballads of the 1990s (which of them are odes to Mavis Staples?); and the special sentimentality seemingly reserved for Baez: “We could sing together in our sleep,” Dylan says of her in Scorsese’s Rolling Thunder Revue (2019). She seemed to remember things a little differently in “Diamonds and Rust” (1975): “My poetry was lousy, you said.“ A man I once loved used to tease me for my clichéd preoccupations with Dylan’s most mawkish of songs about bad love, “Idiot Wind,” but its portrayal of cruelty and masochism is also Dylan at his most usable for feminists. K

K