Lauren Michele Jackson in The New Yorker:

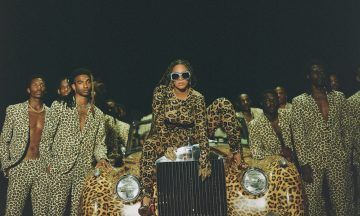

The story of Disney’s “The Lion King,” about a cub who avenges his uncle’s regicide, is said to have borrowed its bones from “Hamlet” (though Marlon James would say otherwise). “Black Is King,” the new “visual album” from Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter, borrows its bones from “The Lion King,” and is comparably interested in rehearsing the drama of its source material—which is to say, not very interested at all. The project is a cinematic adaptation of “The Lion King: The Gift,” the Beyoncé-produced companion album to Disney’s 2019 remake of the film, in which she voiced the part of Nala and for which she created an original song. “Black Is King” follows a young child (Folajomi Akinmurele) whose wayward adventures and visions provoke the question of what kind of man he will become. Royal titles are treated, with urgency, as a means of affirming the innate worth of the human spirit, a message that the film aims especially at the many Black peoples who were long denied the status of human (and, depending on who is asked, still are). Anchored by the lyrical grandeur of its soundtrack, which includes the fourteen songs co-written and co-produced by Beyoncé for “The Gift” (“black parade,” a bonus single on the deluxe edition of the soundtrack, plays during the credits),“Black Is King” expertly slides between talk of bloodlines and molded thrones and more modest—but far from modest—footage of impeccably styled, beautiful Black people in motion.

The story of Disney’s “The Lion King,” about a cub who avenges his uncle’s regicide, is said to have borrowed its bones from “Hamlet” (though Marlon James would say otherwise). “Black Is King,” the new “visual album” from Beyoncé Giselle Knowles-Carter, borrows its bones from “The Lion King,” and is comparably interested in rehearsing the drama of its source material—which is to say, not very interested at all. The project is a cinematic adaptation of “The Lion King: The Gift,” the Beyoncé-produced companion album to Disney’s 2019 remake of the film, in which she voiced the part of Nala and for which she created an original song. “Black Is King” follows a young child (Folajomi Akinmurele) whose wayward adventures and visions provoke the question of what kind of man he will become. Royal titles are treated, with urgency, as a means of affirming the innate worth of the human spirit, a message that the film aims especially at the many Black peoples who were long denied the status of human (and, depending on who is asked, still are). Anchored by the lyrical grandeur of its soundtrack, which includes the fourteen songs co-written and co-produced by Beyoncé for “The Gift” (“black parade,” a bonus single on the deluxe edition of the soundtrack, plays during the credits),“Black Is King” expertly slides between talk of bloodlines and molded thrones and more modest—but far from modest—footage of impeccably styled, beautiful Black people in motion.

…The album’s knowingly ethnic splendor is mesmerizing in its scope; it does not attempt to provide cultural lessons but, rather, invitations to awesome delights. Above all, “Black Is King” is a tribute to the manifold ways that a body can be displayed, from root to toe, dressed up and painted in white, gold, seafoam, lilac, electric green, and pink; in cowhide, denim and tulle, ink, acrylic, lace, leopard, and satin, and fringe; cowry shells and goddess braids; bejewelled everything; good shirts tucked into good chinos; pearl-drenched headdresses, harnesses, thick gold rings; gowns and bleached tips, evening gloves, track jackets, catsuits, tunics, chunky sneakers, mammoth gele; cornrows, ribbon-wrapped feet, cargo pants, and trapezoidal shades. Also, the manifold ways in which a body can move: legwork, footwork, shaku shaku, zanku, twerk, wine, gbese, thrust, grind, shake—the grounded, weight-changing style of choreography that Beyoncé has been fond of since working with the Mozambican trio Tofo Tofo on “Run the World (Girls),” which is prominently shown here in her duet with the Afrobeats artist and divine dancer Stephen Ojo, in “already,” performed with Shatta Wale and Major Lazer. Though Beyoncé, when she appears onscreen, is usually at its center, “Black Is King” also cedes the floor to such charismatic movers as the Afropop artist Yemi Alade, who is featured on “don’t jealous me” and “my power,” alongside the South African artists Moonchild Sanelly and Busiswa and also a supreme slate of professional dancers. There is, in our present moment, a palpable, and reasonable, fatigue when it comes to the superlative showiness of a certain class of celebrity. Some of this sticks to Beyoncé, in particular, given the outsized scale at which she has been working for a while now. But this production—or, rather, the dozens of credited designers, stylists, artists, tailors, architects, weavers, seamstresses, builders, braiders, jewellers, and dancers whose crafts are on display in it—marvels in a way that is difficult to scoff at, especially given that we aren’t likely to see such feats again soon.

More here.

The memoirs of Black revolutionaries have been, almost by definition, exceptional in their narratives, exemplary in their aspirations, and dispirited in their conclusions. Traditionally, the disappointment of unfinished and unrealized ambitions is mitigated by a rhetorical appeal to continued struggle and hope for a future Black liberation that the memoirists themselves will not live to see. They look to the future to say: One day. In time we will find our way to freedom, equality, self-loving, and self-respecting — to fully enjoying whatever the best of the human condition ought to entail. But what if the condition of being human is so thoroughly racialized that even appealing to it only further distances them from the possibility of its realization? What if, moreover, the destruction of Black people is not a contingent difficulty that can be corrected, but a necessary fate because the very category of “the human” is premised on their negation? As Frank Wilderson puts it, what if “Human life is dependent on Black death for its existence and for its conceptual coherence”?

The memoirs of Black revolutionaries have been, almost by definition, exceptional in their narratives, exemplary in their aspirations, and dispirited in their conclusions. Traditionally, the disappointment of unfinished and unrealized ambitions is mitigated by a rhetorical appeal to continued struggle and hope for a future Black liberation that the memoirists themselves will not live to see. They look to the future to say: One day. In time we will find our way to freedom, equality, self-loving, and self-respecting — to fully enjoying whatever the best of the human condition ought to entail. But what if the condition of being human is so thoroughly racialized that even appealing to it only further distances them from the possibility of its realization? What if, moreover, the destruction of Black people is not a contingent difficulty that can be corrected, but a necessary fate because the very category of “the human” is premised on their negation? As Frank Wilderson puts it, what if “Human life is dependent on Black death for its existence and for its conceptual coherence”? We are living, in case you haven’t noticed, in a world full of bullshit. It’s hard to say whether the amount is truly increasing, but it seems that everywhere you look someone is trying to convince you of something, regardless of whether that something is actually true. Where is this bullshit coming from, how is it disseminated, and what can we do about it? Carl Bergstrom studies information in the context of biology, which has led him to investigate the flow of information and disinformation in social networks, especially the use of data in misleading ways. In the time of Covid-19 he has become on of the best Twitter feeds for reliable information, and we discuss how the pandemic has been a bounteous new source of bullshit.

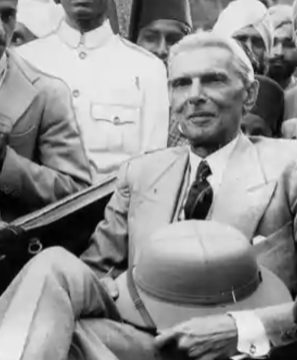

We are living, in case you haven’t noticed, in a world full of bullshit. It’s hard to say whether the amount is truly increasing, but it seems that everywhere you look someone is trying to convince you of something, regardless of whether that something is actually true. Where is this bullshit coming from, how is it disseminated, and what can we do about it? Carl Bergstrom studies information in the context of biology, which has led him to investigate the flow of information and disinformation in social networks, especially the use of data in misleading ways. In the time of Covid-19 he has become on of the best Twitter feeds for reliable information, and we discuss how the pandemic has been a bounteous new source of bullshit. The peculiarity of hindsight is that it depends on the point from which you look back at Pakistan’s and India’s trajectories. In the early 1970s and till the late 1990s, as Pakistan itself broke up into two and generals and mullahs controlled its politics, India could afford to be smug. In 1992, the destruction of the Babri Masjid changed that, and the consequences of India’s 2014 election are there for us to see. Some Pakistanis may feel triumphant, but the virtue of Pakistani lawyer Yasser Latif Hamdani’s new biography, Jinnah: A Life, is that it takes a sober tone.

The peculiarity of hindsight is that it depends on the point from which you look back at Pakistan’s and India’s trajectories. In the early 1970s and till the late 1990s, as Pakistan itself broke up into two and generals and mullahs controlled its politics, India could afford to be smug. In 1992, the destruction of the Babri Masjid changed that, and the consequences of India’s 2014 election are there for us to see. Some Pakistanis may feel triumphant, but the virtue of Pakistani lawyer Yasser Latif Hamdani’s new biography, Jinnah: A Life, is that it takes a sober tone. Bishop published only about a hundred poems during her lifetime, but won the most prestigious prizes for American literature: the Pulitzer in 1956 and the National Book Award in 1970. Brilliant, quirky critic Randall Jarrell described her poems as “honest, modest, minutely observant, masterly. . . . The poems are like Vuillard or even, sometimes, Vermeer.” Bishop was overwhelmed: “It has always been one of my dreams that someday someone would think of Vermeer, without my saying it first”—adding cheerfully, “So now I think I can die in a fairly peaceful frame of mind any old time.” Her life was tumultuous and tragic, but also filled with love and lust. Bishop’s father died when she was only a few months old, a loss her mother, mentally unstable Gertrude Bulmer, never overcame. Her loving, but simple, maternal grandparents raised Bishop in Great Village, a hamlet in Nova Scotia, Canada, during her infancy, while Bulmer was locked up in an insane asylum for long periods. When Bishop was five years old, Bulmer was put away forever, mostly in solitary confinement. She would never see her mother again. Soon after, suddenly, her father’s parents took her to Worcester, Massachusetts, and Bishop ended up in a world that was less austere, but much colder and more distant. Lonely and alone, she was plagued by terrible asthma and eczema; Travisano convincingly argues that these had psychosomatic origins.

Bishop published only about a hundred poems during her lifetime, but won the most prestigious prizes for American literature: the Pulitzer in 1956 and the National Book Award in 1970. Brilliant, quirky critic Randall Jarrell described her poems as “honest, modest, minutely observant, masterly. . . . The poems are like Vuillard or even, sometimes, Vermeer.” Bishop was overwhelmed: “It has always been one of my dreams that someday someone would think of Vermeer, without my saying it first”—adding cheerfully, “So now I think I can die in a fairly peaceful frame of mind any old time.” Her life was tumultuous and tragic, but also filled with love and lust. Bishop’s father died when she was only a few months old, a loss her mother, mentally unstable Gertrude Bulmer, never overcame. Her loving, but simple, maternal grandparents raised Bishop in Great Village, a hamlet in Nova Scotia, Canada, during her infancy, while Bulmer was locked up in an insane asylum for long periods. When Bishop was five years old, Bulmer was put away forever, mostly in solitary confinement. She would never see her mother again. Soon after, suddenly, her father’s parents took her to Worcester, Massachusetts, and Bishop ended up in a world that was less austere, but much colder and more distant. Lonely and alone, she was plagued by terrible asthma and eczema; Travisano convincingly argues that these had psychosomatic origins. In making these claims about academic writing, I am thinking in the first instance of my own corner of academia—philosophy—though I suspect that my points generalize, at least over the academic humanities. To offer up one anecdote: in spring 2019 I was teaching Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; since I don’t usually teach literature, I thought I should check out recent secondary literature on Joyce. What I found was abstruse and hypercomplex, laden with terminology and indirect. I didn’t feel I was learning anything I could use to make the meaning of the novel more accessible to myself or to my students. I am willing to take some of the blame here: I am sure I could have gotten something out of those pieces if I had been willing to put more effort into reading them. Still, I do not lack the intellectual competence required to understand analyses of Joyce; I feel all of those writers could have done more to write for me.

In making these claims about academic writing, I am thinking in the first instance of my own corner of academia—philosophy—though I suspect that my points generalize, at least over the academic humanities. To offer up one anecdote: in spring 2019 I was teaching Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; since I don’t usually teach literature, I thought I should check out recent secondary literature on Joyce. What I found was abstruse and hypercomplex, laden with terminology and indirect. I didn’t feel I was learning anything I could use to make the meaning of the novel more accessible to myself or to my students. I am willing to take some of the blame here: I am sure I could have gotten something out of those pieces if I had been willing to put more effort into reading them. Still, I do not lack the intellectual competence required to understand analyses of Joyce; I feel all of those writers could have done more to write for me.

Back in the ’30s — the 1130s — the Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth created the impression that Stonehenge was built as a memorial to a bunch of British nobles slain by the Saxons. In his “

Back in the ’30s — the 1130s — the Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth created the impression that Stonehenge was built as a memorial to a bunch of British nobles slain by the Saxons. In his “ Many social commentators in the claustrophobic gloom of their self-isolation have shown a tendency to write in somewhat feverish apocalyptic terms about the near future. Some of them expect the pre-existing dysfunctionalities of social and political institutions to accelerate in the post-pandemic world and anticipate our going down a vicious spiral. Others are a bit more hopeful in envisaging a world where the corona crisis will make people wake up to the deep fault lines it has revealed and try to mend things toward a better world. Some others take an intermediate position of what is called upbeat cynicism: hold out for things to be better but guess that will not happen (somewhat akin to Antonio Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”).

Many social commentators in the claustrophobic gloom of their self-isolation have shown a tendency to write in somewhat feverish apocalyptic terms about the near future. Some of them expect the pre-existing dysfunctionalities of social and political institutions to accelerate in the post-pandemic world and anticipate our going down a vicious spiral. Others are a bit more hopeful in envisaging a world where the corona crisis will make people wake up to the deep fault lines it has revealed and try to mend things toward a better world. Some others take an intermediate position of what is called upbeat cynicism: hold out for things to be better but guess that will not happen (somewhat akin to Antonio Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will”). Throughout history there have been prophets of doom and prophets of hope. The prophets of doom are often more visible; the prophets of hope are often more important. The Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg is a prophet of hope. For more than ten years he has been questioning the consensus associated with global warming. Lomborg is not a global warming denier but is a skeptic and realist. He does not question the basic facts of global warming or the contribution of human activity to it. He does not deny that global warming will have some bad effects. But he does question the exaggerated claims, he does question whether it’s the only problem worth addressing, he certainly questions the intense politicization of the issue that makes rational discussion hard and he is critical of the measures being proposed by world governments at the expense of better and cheaper ones. Lomborg is a skeptic who respects the other side’s arguments and tries to refute them with data.

Throughout history there have been prophets of doom and prophets of hope. The prophets of doom are often more visible; the prophets of hope are often more important. The Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg is a prophet of hope. For more than ten years he has been questioning the consensus associated with global warming. Lomborg is not a global warming denier but is a skeptic and realist. He does not question the basic facts of global warming or the contribution of human activity to it. He does not deny that global warming will have some bad effects. But he does question the exaggerated claims, he does question whether it’s the only problem worth addressing, he certainly questions the intense politicization of the issue that makes rational discussion hard and he is critical of the measures being proposed by world governments at the expense of better and cheaper ones. Lomborg is a skeptic who respects the other side’s arguments and tries to refute them with data.