Servaas Storm over at INET (with comments by Joseph Halevi and Peter Kriesler, Duncan Foley, and Thomas Ferguson here):

Servaas Storm over at INET (with comments by Joseph Halevi and Peter Kriesler, Duncan Foley, and Thomas Ferguson here):

Questions about the decline of Social democracy continue to excite wide interest, even in the era of Covid-19. This paper takes a fresh look at topic. It argues that social democratic politics faces a fundamental dilemma: short-term practical relevance requires it to accept, at least partly, the very socio-economic conditions which it purports to change in the longer run. Bhaduri’s (1993) essay which analyzes social democracy’s attempts to navigate this dilemma by means of ‘a nationalization of consumption’ and Keynesian demand management, was written before the rise of New (‘Third Way’) Labor and before the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-8. This paper provides an update, arguing that New Labor’s attempt to rescue ‘welfare capitalism’ entailed a new solution to the dilemma facing social democracy based on an expansion of employment, i.e. an all-out emphasis on “jobs, jobs, jobs”. The flip-side (or social cost) of the emphasis on job growth has been a stagnation of productivity growth—which, in turn, has put the ‘welfare state’ under increasing pressure of fiscal austerity. The popular discontent and rise of ‘populist’ political parties is closely related to the failure of New Labor to navigate social democracy’s dilemma.

More here.

Adam Tooze in Foreign Policy:

Adam Tooze in Foreign Policy: Andrew Whitehead in The Wire:

Andrew Whitehead in The Wire: Astra Taylor talks to Rutgers faculty union president Todd Wolfson, over at Boston Review:

Astra Taylor talks to Rutgers faculty union president Todd Wolfson, over at Boston Review: The Immanent Frame has

The Immanent Frame has  Hot Springs, as David Hill writes in “The Vapors,” a history of the town during its sin-soaked heyday, let a lot of people be — with varying degrees of vengeance. Among them were workaday gamblers and good-timers like Kelley, but also bookmakers, con artists, prostitutes, shills, crooked auctioneers, outlandishly corrupt politicians and boldface-named mobsters. From about 1870 until 1967, when the reformist governor Winthrop Rockefeller shut off the vice spigot, the town’s chief municipal expression was a wink. The mayors winked. The cops winked. The preachers winked, or at least averted their gaze. Winking was how a Bible Belt town of 28,000 (circa 1960) attracted upward of five million visitors per year and why, as Hill writes, on any given Saturday night, there may have been “no more exhilarating place to be in the entire country.”

Hot Springs, as David Hill writes in “The Vapors,” a history of the town during its sin-soaked heyday, let a lot of people be — with varying degrees of vengeance. Among them were workaday gamblers and good-timers like Kelley, but also bookmakers, con artists, prostitutes, shills, crooked auctioneers, outlandishly corrupt politicians and boldface-named mobsters. From about 1870 until 1967, when the reformist governor Winthrop Rockefeller shut off the vice spigot, the town’s chief municipal expression was a wink. The mayors winked. The cops winked. The preachers winked, or at least averted their gaze. Winking was how a Bible Belt town of 28,000 (circa 1960) attracted upward of five million visitors per year and why, as Hill writes, on any given Saturday night, there may have been “no more exhilarating place to be in the entire country.” In her 1999 book Hiroshima Traces, the anthropologist Lisa Yoneyama describes the hibakusha’s intense relationship with the dead differently from Lifton’s ‘death in life’. Yoneyama sees the hibakusha as giving the bomb’s victims life after death. She writes that the hibakusha have developed ‘testimonial practices’ that can be compared to ‘a shamanistic ritual that summons dead souls’, to ‘resurrect the deceased and endow them with voices’.

In her 1999 book Hiroshima Traces, the anthropologist Lisa Yoneyama describes the hibakusha’s intense relationship with the dead differently from Lifton’s ‘death in life’. Yoneyama sees the hibakusha as giving the bomb’s victims life after death. She writes that the hibakusha have developed ‘testimonial practices’ that can be compared to ‘a shamanistic ritual that summons dead souls’, to ‘resurrect the deceased and endow them with voices’. Space, as they say, is big. In The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979), Douglas Adams elaborates: ‘You may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s just peanuts to space.’ It’s hard to convey in everyday terms the enormity of the cosmos when most of us have trouble even visualising the size of the Earth, much less the galaxy, or the vast expanses of intergalactic space. We often talk in terms of light-years – the distance light can travel in a year – as though the speed of light is somehow more intuitive than a number written in the trillions of kilometres. We give benchmarks in the same terms (it takes light 1.3 seconds to travel between the Earth and the Moon) but, in our everyday experience, light is instantaneous. We might as well talk about the height of a building in terms of stacking up atoms.

Space, as they say, is big. In The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979), Douglas Adams elaborates: ‘You may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s just peanuts to space.’ It’s hard to convey in everyday terms the enormity of the cosmos when most of us have trouble even visualising the size of the Earth, much less the galaxy, or the vast expanses of intergalactic space. We often talk in terms of light-years – the distance light can travel in a year – as though the speed of light is somehow more intuitive than a number written in the trillions of kilometres. We give benchmarks in the same terms (it takes light 1.3 seconds to travel between the Earth and the Moon) but, in our everyday experience, light is instantaneous. We might as well talk about the height of a building in terms of stacking up atoms.

As in a fairy tale, the cities, to defend themselves from an invisible yet powerful enemy, have disappeared: they have gone into exile. They have declared themselves banned, outlawed, and now they lie before us like inside an archaeological museum or a diorama.

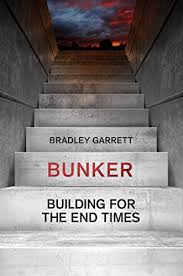

As in a fairy tale, the cities, to defend themselves from an invisible yet powerful enemy, have disappeared: they have gone into exile. They have declared themselves banned, outlawed, and now they lie before us like inside an archaeological museum or a diorama. But the word ‘bunker’ also has the scent of modernity about it. As Bradley Garrett explains in his book, it was a corollary of the rise of air power, as a result of which the battlefield became three-dimensional. With the enemy above and equipped with high explosives, you had to dig down and protect yourself with metres of concrete. Garrett’s previous book, Explore Everything, was a fascinating insider’s look at illicit ‘urban exploration’, and he kicks off Bunker with an account of time spent poking around the Burlington Bunker, which would have been used by the UK government in the event of a nuclear war. The Cold War may have ended, but governments still build bunkers, as Garrett shows: Chinese contractors have recently completed a 23,000-square-metre complex in Djibouti. But these grand, often secret manifestations of official fear are not the main focus of the book. Instead, Garrett is interested in private bunkers and the people who build them, people like Robert Vicino, founder of the Vivos Group, who purchased the Burlington Bunker with the intent of making a worldwide chain of apocalypse retreats.

But the word ‘bunker’ also has the scent of modernity about it. As Bradley Garrett explains in his book, it was a corollary of the rise of air power, as a result of which the battlefield became three-dimensional. With the enemy above and equipped with high explosives, you had to dig down and protect yourself with metres of concrete. Garrett’s previous book, Explore Everything, was a fascinating insider’s look at illicit ‘urban exploration’, and he kicks off Bunker with an account of time spent poking around the Burlington Bunker, which would have been used by the UK government in the event of a nuclear war. The Cold War may have ended, but governments still build bunkers, as Garrett shows: Chinese contractors have recently completed a 23,000-square-metre complex in Djibouti. But these grand, often secret manifestations of official fear are not the main focus of the book. Instead, Garrett is interested in private bunkers and the people who build them, people like Robert Vicino, founder of the Vivos Group, who purchased the Burlington Bunker with the intent of making a worldwide chain of apocalypse retreats.

“The Well” is distinctive in the sheer fact of its characterizations and dramatizations—it depicts, alongside its white characters, a wide variety of Black characters in a wide range of settings (work, school, home, government offices, street life), speaking substantially (if briefly) about the trouble at hand and their views of it. From the start, the movie dispels all ambiguity: Carolyn, who loved flowers, walks through an empty field on the way to school and falls into a long-abandoned well. Her teacher, a white woman, reports her absence to Carolyn’s mother, Martha (Maidie Norman), who informs the town’s sheriff, Ben Kellog (Richard Rober), a white man. Despite the frank assertion of Carolyn’s uncle, Gaines (Alfred Grant), that the police won’t be looking very hard for a Black child, Ben sharply declares and clearly displays his authentic concern, energetically and devotedly sending more or less the entire police force—all white men—to scour the town for Carolyn.

“The Well” is distinctive in the sheer fact of its characterizations and dramatizations—it depicts, alongside its white characters, a wide variety of Black characters in a wide range of settings (work, school, home, government offices, street life), speaking substantially (if briefly) about the trouble at hand and their views of it. From the start, the movie dispels all ambiguity: Carolyn, who loved flowers, walks through an empty field on the way to school and falls into a long-abandoned well. Her teacher, a white woman, reports her absence to Carolyn’s mother, Martha (Maidie Norman), who informs the town’s sheriff, Ben Kellog (Richard Rober), a white man. Despite the frank assertion of Carolyn’s uncle, Gaines (Alfred Grant), that the police won’t be looking very hard for a Black child, Ben sharply declares and clearly displays his authentic concern, energetically and devotedly sending more or less the entire police force—all white men—to scour the town for Carolyn. Each of us has been affected by the changes wrought by COVID-19 in different ways. For some, the period of isolation has afforded time for contemplation. How do the ways in which our societies are currently structured enable crises such as this? How might we organise them otherwise? How might we use this opportunity to address other pressing global challenges, such climate change or racism?

Each of us has been affected by the changes wrought by COVID-19 in different ways. For some, the period of isolation has afforded time for contemplation. How do the ways in which our societies are currently structured enable crises such as this? How might we organise them otherwise? How might we use this opportunity to address other pressing global challenges, such climate change or racism? “What is it,” the Austro-Hungarian novelist Joseph Roth asked rhetorically in 1927, in a preface to his book The Wandering Jews, “that allows European states to go spreading civilisation and ethics in foreign parts but not at home?” Forty years later, as American cities burned while American bombs rained down on Vietnam, James Baldwin made a similar point, though reversing Roth’s formulation. “A racist society,” he wrote, “can’t but fight a racist war – this is the bitter truth. The assumptions acted on at home are also acted on abroad.”

“What is it,” the Austro-Hungarian novelist Joseph Roth asked rhetorically in 1927, in a preface to his book The Wandering Jews, “that allows European states to go spreading civilisation and ethics in foreign parts but not at home?” Forty years later, as American cities burned while American bombs rained down on Vietnam, James Baldwin made a similar point, though reversing Roth’s formulation. “A racist society,” he wrote, “can’t but fight a racist war – this is the bitter truth. The assumptions acted on at home are also acted on abroad.”