Gail Russell Chadock in The Christian Science Monitor:

We never knew why my father took over storytelling for his three little girls, but we always suspected it was to save us from “Sleeping Beauty.” Walt Disney’s masterwork hit the big suburban screens in 1959 with a message for girls as vivid as its widescreen Technirama: If you’re pretty enough, a prince will rescue you. In a masterstroke of counterprogramming, my father invented a series of bedtime stories featuring three princesses who happened to be just our ages and even looked like us. For some reason, the grownups were never around when peril struck. So, night after night, it was up to the three sisters to save the village, which they always managed to do just about the time that one of us fell asleep. It did occur to us that this village was either highly unfortunate or its adults incredibly inept that so much fell to these little girls. We also saw that our parents wanted us to be strong. These girls didn’t need to be rescued. They were alert, wise, and bold. That was enough. But how to carry this storyline into life was not obvious. The fifth-grade teacher might like you if you raised your hand in class, but what about the boy you hoped would ask you to dance? Experience showed that boldness could have a downside.

We never knew why my father took over storytelling for his three little girls, but we always suspected it was to save us from “Sleeping Beauty.” Walt Disney’s masterwork hit the big suburban screens in 1959 with a message for girls as vivid as its widescreen Technirama: If you’re pretty enough, a prince will rescue you. In a masterstroke of counterprogramming, my father invented a series of bedtime stories featuring three princesses who happened to be just our ages and even looked like us. For some reason, the grownups were never around when peril struck. So, night after night, it was up to the three sisters to save the village, which they always managed to do just about the time that one of us fell asleep. It did occur to us that this village was either highly unfortunate or its adults incredibly inept that so much fell to these little girls. We also saw that our parents wanted us to be strong. These girls didn’t need to be rescued. They were alert, wise, and bold. That was enough. But how to carry this storyline into life was not obvious. The fifth-grade teacher might like you if you raised your hand in class, but what about the boy you hoped would ask you to dance? Experience showed that boldness could have a downside.

By the 1970s, there was a cottage industry explaining to women what was holding them back. We needed mentors, networks, and constant vigilance to manage our careers and break through the invisible “glass ceiling” limiting our progress. But in my early experience, glass ceilings were not often invisible. Women were just beginning to be admitted to what had been men-only colleges, and teaching jobs followed. Some who were not pleased showed it. I loved to tell my network about the welcome dinner for new graduate students in a vast, candlelit Gothic hall. I sat next to the dean of the graduate school, whose first words to me were: “I don’t know why the graduate school is now admitting women. You’ll all just get married, have babies, and your education will be wasted.”

After a few days to recover, I began telling friends this story and found their laughter and support encouraging. Soon, I had accumulated many such stories, all hilarious when told from my point of view. There was the department chair who told me at our first meeting that he used math requirements “to keep little girls out of the program.” Or the job interview that opened with the question: “Isn’t it amazing how so many unqualified women are now getting job interviews?” All good for laughs. Then, one of them hit hard. A colleague I trusted urged me, soberly, to quit teaching, because “If you don’t leave political science, you will lose everything feminine about you.” In today’s culture, that remark goes straight to laugh line. But on that day, in that place, something went crash. I walked back to my rented apartment over a garage convinced that my career was over. That’s usually a time to call a mentor, but he was the mentor. Nor was it a moment to enlist the network. Pity or encouragement both seemed intolerable.

In the quiet that followed, I opened a Bible, looking for any thought more inspiring than my own. Here’s the first thing I read: “How long will thou go about, O thou backsliding daughter? for the Lord hath created a new thing in the earth, A woman shall compass a man.” (Jeremiah 31:22).

More here.

Eileen Blair, George Orwell’s first wife, is the subject of this welcome and assiduously researched biography by Sylvia Topp. Eileen married Orwell in 1936 when he was a virtual unknown and, until her death in 1945 at the age of just thirty-nine, shared with him a life that was lived primarily on the unreliable income from his writing. She did not live to see even the beginnings of the worldwide fame that would come her husband’s way with Animal Farm, which was published in the year of her death.

Eileen Blair, George Orwell’s first wife, is the subject of this welcome and assiduously researched biography by Sylvia Topp. Eileen married Orwell in 1936 when he was a virtual unknown and, until her death in 1945 at the age of just thirty-nine, shared with him a life that was lived primarily on the unreliable income from his writing. She did not live to see even the beginnings of the worldwide fame that would come her husband’s way with Animal Farm, which was published in the year of her death.

Immediately afterwards, the paintings take a turn towards our grosser world, and the realism begins to hurt. The portrait of John Minton has a piercing sadness. The portrait of Francis Bacon with lowered eyes has a Germanic intensity; it’s as if Grunewald had started a noli me tangere. The wide-eyed girl appears once more, in a green dressing gown, with a dog resting its head in her lap, but she has come back to our edgy, nerve-ridden world. Another girl appears. She has yellow hair and a charming face, and the images of her are still controlled by line.

Immediately afterwards, the paintings take a turn towards our grosser world, and the realism begins to hurt. The portrait of John Minton has a piercing sadness. The portrait of Francis Bacon with lowered eyes has a Germanic intensity; it’s as if Grunewald had started a noli me tangere. The wide-eyed girl appears once more, in a green dressing gown, with a dog resting its head in her lap, but she has come back to our edgy, nerve-ridden world. Another girl appears. She has yellow hair and a charming face, and the images of her are still controlled by line. We are used to thinking of idleness as a vice, something to be ashamed of. But when the British philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote “

We are used to thinking of idleness as a vice, something to be ashamed of. But when the British philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote “ What is

What is  When it comes to many philosophical issues, people feel conflicted or confused. There is something drawing them toward one intuition but also something drawing them toward the exact opposite intuition. This tension seems to be an important aspect of what makes us regard these issues as important philosophical problems in the first place.

When it comes to many philosophical issues, people feel conflicted or confused. There is something drawing them toward one intuition but also something drawing them toward the exact opposite intuition. This tension seems to be an important aspect of what makes us regard these issues as important philosophical problems in the first place. It’s easy to foresee that technological progress will change how we live; it’s much harder to anticipate exactly how. Self-driving cars represent an enormous technological challenge, but one that is plausibly on the way to being solved. What will be the unanticipated consequences when autonomous vehicles become commonplace? Jason Torchinsky is a fan of technology, but also a fan of driving, and his recent book Robot, Take the Wheel examines how our relationship with cars is likely to change in the near future.

It’s easy to foresee that technological progress will change how we live; it’s much harder to anticipate exactly how. Self-driving cars represent an enormous technological challenge, but one that is plausibly on the way to being solved. What will be the unanticipated consequences when autonomous vehicles become commonplace? Jason Torchinsky is a fan of technology, but also a fan of driving, and his recent book Robot, Take the Wheel examines how our relationship with cars is likely to change in the near future. On July 17, President Donald Trump sat for a

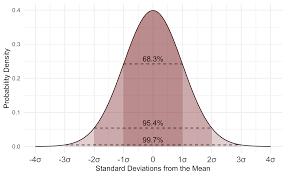

On July 17, President Donald Trump sat for a  Statistics in the Progressive Era were more than mere signs of a managerial government’s early efforts to sort and categorize its citizens. The emergence of statistical selves was not simply a rationalization of everyday life, a search for order (as Robert Wiebe taught a half century of historians to say). The reliance on statistical governance coincided with and complemented a pervasive revaluation of primal spontaneity and vitality, an effort to unleash hidden strength from an elusive inner self. The collectivization epitomized in the quantitative turn was historically compatible with radically individualist agendas for personal regeneration—what later generations would learn to call positive thinking.

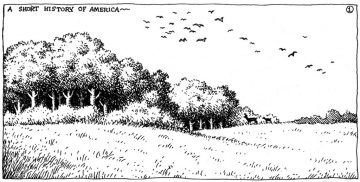

Statistics in the Progressive Era were more than mere signs of a managerial government’s early efforts to sort and categorize its citizens. The emergence of statistical selves was not simply a rationalization of everyday life, a search for order (as Robert Wiebe taught a half century of historians to say). The reliance on statistical governance coincided with and complemented a pervasive revaluation of primal spontaneity and vitality, an effort to unleash hidden strength from an elusive inner self. The collectivization epitomized in the quantitative turn was historically compatible with radically individualist agendas for personal regeneration—what later generations would learn to call positive thinking. The comic is bookended by two pieces of nondiegetic text. We start with the title hovering above a pastoral scene, nature as yet unspoiled: trees, deer, birds, and a gently sloping hill. We can safely assume this is America, but when? It could be yesterday, or thousands of years ago. We deduce that the second panel shows this same setting not long after, because of a key continuity: the trees, placed in the same position inside the two panels, haven’t grown much. Our eyes adjust quickly to repetition and become acutely sensitive to any deviation, however small. Instantly, we take in the hill and felled trees, along with the introduction of the railroad track, upon which chugs a small train, billowing steam as it disappears into the distance. The wild animals are gone, a visual shorthand for the encroachment of humans. Because of the train’s presence, we infer that these first two panels take place in the early-to-mid-nineteenth century. In the third panel, a few birds glide in the sky, recalling the first panel. The hill remains in the scene (though altered), as well as the train track, but years must have passed, because we also see a house, shed, and cart (signifying “farm”), as well as a dirt road (signifying “town”), telegraph wires, and a man with horse and buggy. Will this fellow be our main character?

The comic is bookended by two pieces of nondiegetic text. We start with the title hovering above a pastoral scene, nature as yet unspoiled: trees, deer, birds, and a gently sloping hill. We can safely assume this is America, but when? It could be yesterday, or thousands of years ago. We deduce that the second panel shows this same setting not long after, because of a key continuity: the trees, placed in the same position inside the two panels, haven’t grown much. Our eyes adjust quickly to repetition and become acutely sensitive to any deviation, however small. Instantly, we take in the hill and felled trees, along with the introduction of the railroad track, upon which chugs a small train, billowing steam as it disappears into the distance. The wild animals are gone, a visual shorthand for the encroachment of humans. Because of the train’s presence, we infer that these first two panels take place in the early-to-mid-nineteenth century. In the third panel, a few birds glide in the sky, recalling the first panel. The hill remains in the scene (though altered), as well as the train track, but years must have passed, because we also see a house, shed, and cart (signifying “farm”), as well as a dirt road (signifying “town”), telegraph wires, and a man with horse and buggy. Will this fellow be our main character? We never knew why my father took over storytelling for his three little girls, but we always suspected it was to save us from “Sleeping Beauty.” Walt Disney’s masterwork hit the big suburban screens in 1959 with a message for girls as vivid as its widescreen Technirama: If you’re pretty enough, a prince will rescue you. In a masterstroke of counterprogramming, my father invented a series of bedtime stories featuring three princesses who happened to be just our ages and even looked like us. For some reason, the grownups were never around when peril struck. So, night after night, it was up to the three sisters to save the village, which they always managed to do just about the time that one of us fell asleep. It did occur to us that this village was either highly unfortunate or its adults incredibly inept that so much fell to these little girls. We also saw that our parents wanted us to be strong. These girls didn’t need to be rescued. They were alert, wise, and bold. That was enough. But how to carry this storyline into life was not obvious. The fifth-grade teacher might like you if you raised your hand in class, but what about the boy you hoped would ask you to dance? Experience showed that boldness could have a downside.

We never knew why my father took over storytelling for his three little girls, but we always suspected it was to save us from “Sleeping Beauty.” Walt Disney’s masterwork hit the big suburban screens in 1959 with a message for girls as vivid as its widescreen Technirama: If you’re pretty enough, a prince will rescue you. In a masterstroke of counterprogramming, my father invented a series of bedtime stories featuring three princesses who happened to be just our ages and even looked like us. For some reason, the grownups were never around when peril struck. So, night after night, it was up to the three sisters to save the village, which they always managed to do just about the time that one of us fell asleep. It did occur to us that this village was either highly unfortunate or its adults incredibly inept that so much fell to these little girls. We also saw that our parents wanted us to be strong. These girls didn’t need to be rescued. They were alert, wise, and bold. That was enough. But how to carry this storyline into life was not obvious. The fifth-grade teacher might like you if you raised your hand in class, but what about the boy you hoped would ask you to dance? Experience showed that boldness could have a downside. Two years ago, Jennifer Li and Drew Robson were trawling through terabytes of data from a zebrafish-brain experiment when they came across a handful of cells that seemed to be psychic. The two neuroscientists had planned to map brain activity while zebrafish larvae were hunting for food, and to see how the neural chatter changed. It was their first major test of a technological platform they had built at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The platform allowed them to view every cell in the larvae’s brains while the creatures — barely the size of an eyelash — swam freely in a 35-millimetre-diameter dish of water, snacking on their microscopic prey.

Two years ago, Jennifer Li and Drew Robson were trawling through terabytes of data from a zebrafish-brain experiment when they came across a handful of cells that seemed to be psychic. The two neuroscientists had planned to map brain activity while zebrafish larvae were hunting for food, and to see how the neural chatter changed. It was their first major test of a technological platform they had built at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The platform allowed them to view every cell in the larvae’s brains while the creatures — barely the size of an eyelash — swam freely in a 35-millimetre-diameter dish of water, snacking on their microscopic prey.

We have argued in

We have argued in