Month: June 2020

How Pyrrhonism, a branch of ancient skepticism, can help us navigate today’s turbulent waters

Rachel Ashcroft in Arc Digital:

Even the way in which coronavirus data is presented can radically change our perception of its impact, depending on which factors have been included and which have been discarded.

Even the way in which coronavirus data is presented can radically change our perception of its impact, depending on which factors have been included and which have been discarded.

The confusion over what works and what doesn’t can leave us feeling deeply overwhelmed.

It’s little wonder, then, that in this anxiety-riddled time many are turning to Stoicism and its promise of courage and calm. However, I’d like to recommend something different. Pyrrhonism, a lesser-known philosophy from the same time as Stoicism, argues that we don’t know how things around us really are. Let’s give it a closer look, since this seems to be the very epistemic position we seem to find ourselves in today.

More here.

Turkish Female Singers and Anatolian Pop

On Boredom and Bad Smells

Mary Gordon at Salmagundi:

They have always been with me, these two fears: of boredom and bad smells. I have no memory of a life free of them.

They have always been with me, these two fears: of boredom and bad smells. I have no memory of a life free of them.

We like to think that children are not bored. That what we call boredom is not open to them. That what is being called boredom must be something else: petulance, a too demanding nature, plain fatigue. We assume that children can be easily distracted and that if the distraction doesn’t work, another one can easily be found to take its place. This is simply not true. So much of the life of a child is a flat, unbroken plain, a nullity, a waiting for something, a waiting more painful than an adult’s because often what is desired cannot yet be named. I know that I was often bored as a child, and I can trace the reasons. I was not good at being a child. I did not find interesting the things that children were supposed to find interesting.

more here.

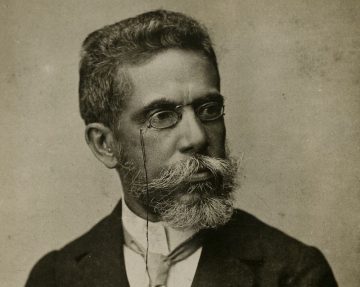

Machado’s Catalogue of Failures

Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson at The Paris Review:

The literary models Machado mentions in his preface are Laurence Sterne, Xavier de Maistre, and Almeida Garrett, but behind the title there may also be an ironic reference to Chateaubriand’s Mémoires d’outre-tombe (Memoirs from Beyond the Grave), published posthumously in 1849 and 1850. Those memoirs filled two volumes; their author was a diplomat, politician, writer, historian, and supposed founder of French Romanticism. Brás Cubas’s posthumous memoirs (which are written from beyond the grave) fill a scant two hundred pages and the narrator is, by his own blithe admission, a complete mediocrity whose life can be summed up by a series of negatives. Echoes of Sterne, Maistre, and Garrett are definitely all there in the brief chapters, the oblique chapter titles, the non sequiturs, and the half-baked philosophy, and yet in many ways the book is also a straightforward nineteenth-century realist novel, with its jabs at the hypocrisy of middle-class society, and the standard themes of adultery, money, marriage, miserliness, and profligacy. Machado manages, seamlessly, to combine realism and the fantastic, and the novel’s fragmentary, allusive style and its frequent inclusion of us, the readers, strikes us now as very modern, as does Brás Cubas’s insistence, more than once, that this is not a novel at all.

The literary models Machado mentions in his preface are Laurence Sterne, Xavier de Maistre, and Almeida Garrett, but behind the title there may also be an ironic reference to Chateaubriand’s Mémoires d’outre-tombe (Memoirs from Beyond the Grave), published posthumously in 1849 and 1850. Those memoirs filled two volumes; their author was a diplomat, politician, writer, historian, and supposed founder of French Romanticism. Brás Cubas’s posthumous memoirs (which are written from beyond the grave) fill a scant two hundred pages and the narrator is, by his own blithe admission, a complete mediocrity whose life can be summed up by a series of negatives. Echoes of Sterne, Maistre, and Garrett are definitely all there in the brief chapters, the oblique chapter titles, the non sequiturs, and the half-baked philosophy, and yet in many ways the book is also a straightforward nineteenth-century realist novel, with its jabs at the hypocrisy of middle-class society, and the standard themes of adultery, money, marriage, miserliness, and profligacy. Machado manages, seamlessly, to combine realism and the fantastic, and the novel’s fragmentary, allusive style and its frequent inclusion of us, the readers, strikes us now as very modern, as does Brás Cubas’s insistence, more than once, that this is not a novel at all.

more here.

The Blood of the Lamb

Davis Steensma in JCO:

Peter De Vries (1910–1993)—writer for the New Yorker, Poetry editor, once widely acknowledged as the top American comic novelist of his era—was best known for his clever wordplay, irreverent humor, and extended riffs on a broad range of human foibles.1–3 But despite De Vries’ reputation for puckish wit and for the skewering bon mot, his greatest novel is a tragedy—one that is all the more haunting because it is stuffed with autobiographical detail. The Blood of the Lamb, 4 published in 1961, describes the growing estrangement of the main character (Don Wanderhope) from his origins in a close-knit, blue-collar, Chicagoland Dutch immigrant community. The death of a sibling, parental mental illness, and the strains of a volatile marriage contracted too hastily were heavy stones that stressed the increasingly rickety structure of Wanderhope’s boyhood religious faith, until that faith finally collapsed beneath the crush of a singular and devastating loss, re-emerging as something more ambiguous. Emily De Vries—her literary counterpart is Carol Wanderhope—De Vries’ youngest child and a chief existential consolation, died in September 1960, just a few days before her 11th birthday and 2 years after she was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).1

Peter De Vries (1910–1993)—writer for the New Yorker, Poetry editor, once widely acknowledged as the top American comic novelist of his era—was best known for his clever wordplay, irreverent humor, and extended riffs on a broad range of human foibles.1–3 But despite De Vries’ reputation for puckish wit and for the skewering bon mot, his greatest novel is a tragedy—one that is all the more haunting because it is stuffed with autobiographical detail. The Blood of the Lamb, 4 published in 1961, describes the growing estrangement of the main character (Don Wanderhope) from his origins in a close-knit, blue-collar, Chicagoland Dutch immigrant community. The death of a sibling, parental mental illness, and the strains of a volatile marriage contracted too hastily were heavy stones that stressed the increasingly rickety structure of Wanderhope’s boyhood religious faith, until that faith finally collapsed beneath the crush of a singular and devastating loss, re-emerging as something more ambiguous. Emily De Vries—her literary counterpart is Carol Wanderhope—De Vries’ youngest child and a chief existential consolation, died in September 1960, just a few days before her 11th birthday and 2 years after she was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).1

Through the filter of his prodigious literary gifts, De Vries poured out the monstrous, idiosyncratic grief of a bereft father, of a man who has lost something that really matters. The Blood of the Lamb was published just a year after Emily’s death, and the rawness of emotion sears its pages: often bitter, sometimes elegiac, and with scattered patches where the writing is less polished, less subtle than is typical for De Vries.4 The author’s seething anger over the unfairness of the world is frequently channeled into frustration at a paternalistic and ultimately impotent medical establishment, which provided plenty of facile reassurances, even as it failed to save his innocent “lamb” of a daughter from her own poisoned blood.

De Vries eventually returned to writing comic novels after The Blood of the Lamb, but always with darker undertones, echoing the futility and chaotic meaninglessness of life that he felt so acutely during Emily’s terminal illness.1,2 These stylistic changes parallel the intellectual evolution of Charles Darwin a century earlier, after a similar event: Darwin lost his beloved daughter Annie in 1851, also at age 10 years from an unexplained illness—possibly tuberculosis, which was just as frightening and incurable in the 1850s as leukemia a century later.5 Darwin’s great-grandson suggests that the feelings of randomness and lack of ultimate purpose engendered by Annie Darwin’s untimely death pushed the great naturalist towards a reluctant full acknowledgment of the terrifying metaphysical implications of his mechanism of natural selection.5,6 The legacy of a child’s premature death can be long indeed.

More here. (Note: An old novel worth re-reading. Thanks David.)

Surprise! Justice on L.G.B.T. Rights From a Trump Judge

Michelle Goldberg in The New York Times:

The new season of my favorite television show, “The Good Fight,” begins with the heroine, the feminist lawyer Diane Lockhart, awakening in what seems at first like a giddy alternative reality in which Hillary Clinton won the 2016 election. She remembers the horrors of the last three and a half years, but no one else seems to. A crushing weight lifts as she convinces herself it was all an awful dream. Then she is sent to a meeting with her firm’s new client, Harvey Weinstein. There’s been no #MeToo movement. Instead, corporate “lean in” feminism is at its apogee. Diane realizes there have been gains made since Donald Trump took office that are unbearable to give up. Obviously, a world in which Clinton beat Trump would be better in a million ways. Still, right now we have two big examples of how Trump’s perverse presidency has inadvertently led to progress. The sudden, rapid embrace of the Black Lives Matter movement by white people is a function of the undeniable brutality of George Floyd’s videotaped killing. But public opinion has also moved left on racial issues in reaction to an unpopular president who behaves like a cross between Bull Connor and Andrew Dice Clay.

The new season of my favorite television show, “The Good Fight,” begins with the heroine, the feminist lawyer Diane Lockhart, awakening in what seems at first like a giddy alternative reality in which Hillary Clinton won the 2016 election. She remembers the horrors of the last three and a half years, but no one else seems to. A crushing weight lifts as she convinces herself it was all an awful dream. Then she is sent to a meeting with her firm’s new client, Harvey Weinstein. There’s been no #MeToo movement. Instead, corporate “lean in” feminism is at its apogee. Diane realizes there have been gains made since Donald Trump took office that are unbearable to give up. Obviously, a world in which Clinton beat Trump would be better in a million ways. Still, right now we have two big examples of how Trump’s perverse presidency has inadvertently led to progress. The sudden, rapid embrace of the Black Lives Matter movement by white people is a function of the undeniable brutality of George Floyd’s videotaped killing. But public opinion has also moved left on racial issues in reaction to an unpopular president who behaves like a cross between Bull Connor and Andrew Dice Clay.

And the thrilling 6-3 decision the Supreme Court just issued upholding L.G.B.T. equality wouldn’t be as devastating to the religious right if it had happened under a President Clinton. Before Monday, you could legally be fired for being gay, bisexual or transgender in 26 states. Now the court has ruled that gay and transgender people are protected by Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which prohibits employment discrimination on the basis of sex. The decision has extra cultural force because it was written by Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, and joined by the conservative chief justice John Roberts. “The whole point of the Federalist Society judicial project, the whole point of electing Trump to implement it, was to deliver Supreme Court victories to social conservatives,” tweeted the conservative writer Varad Mehta. “If they can’t deliver anything that basic, there’s no point for either. The damage is incalculable.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

This World Which Is Made of Our Love for Emptiness

Praise to the emptiness that blanks out existence. Existence:

This place made from our love for that emptiness!

Yet somehow comes emptiness,

this existence goes.

Praise to that happening, over and over!

For years I pulled my own existence out of emptiness.

Then one swoop, one swing of the arm,

that work is over.

Free of who I was, free of presence, free of dangerous fear, hope,

free of mountainous wanting.

The here-and-now mountain is a tiny piece of a piece of straw

blown off into emptiness.

These words I’m saying so much begin to lose meaning:

Existence, emptiness, mountain, straw:

Words and what they try to say swept

out the window, down the slant of the roof.

Fihi ma fihi [Discourses of Rumi]

from The Sufi Path of Love: The Spiritual Teachings of Rumi, William C. Chittick, Albany: SUNY, 1983

Reflections on a post-corona-time by William Pierce and others

William Pierce at the website of the Goethe Institut:

Yesterday I went food shopping in the now quasi-military operation of a big grocery store near Boston. Near the entrance, I stopped to take a picture of an advertising placard—one of the neighboring stores touting its “Spring 2020 bridal collection.” It’s harder than usual to begrudge people their attempts to make money right now. We’ve learned how fragile the world’s systems of income are, even for those who make far more than they need. Airlines’ business can evaporate from one week to the next. Hotels can empty overnight. Who knew it could happen everywhere across the world at once? So there was pathos in the timing of the ad, which was very likely to fail. But the reason I stopped to take a picture, and the reason the picture has become a symbol of the moment for me: it featured an airbrushed photograph of a tall, white, easygoing, never-in-her-life-hungry bride—and passing behind her, from my frame of reference though of course not the bride’s, was a woman in blue nitrile gloves and a face mask, pushing a shopping cart back toward her isolation.

Yesterday I went food shopping in the now quasi-military operation of a big grocery store near Boston. Near the entrance, I stopped to take a picture of an advertising placard—one of the neighboring stores touting its “Spring 2020 bridal collection.” It’s harder than usual to begrudge people their attempts to make money right now. We’ve learned how fragile the world’s systems of income are, even for those who make far more than they need. Airlines’ business can evaporate from one week to the next. Hotels can empty overnight. Who knew it could happen everywhere across the world at once? So there was pathos in the timing of the ad, which was very likely to fail. But the reason I stopped to take a picture, and the reason the picture has become a symbol of the moment for me: it featured an airbrushed photograph of a tall, white, easygoing, never-in-her-life-hungry bride—and passing behind her, from my frame of reference though of course not the bride’s, was a woman in blue nitrile gloves and a face mask, pushing a shopping cart back toward her isolation.

A butterfly named Flamingo, an epic migration, and the crusade to save one of America’s most iconic species

Nora Caplan-Bricker in The Atavist:

The phenomenon that some people in Brookings, Oregon, would later call a miracle began in early July 2019, when the same monarch butterfly appeared in Holly Beyer’s yard almost every day for two weeks. Beyer recognized it by a scratch on one wing. She and a friend named it Ovaltine, inspired by ovum, for the way it encrusted the milkweed in Beyer’s garden with eggs. Each off-white bump was no larger than the tip of a sharpened pencil. Clustered together on the green leaves, they looked like blemishes, as if the milkweed had sprouted a case of adolescent acne.

The phenomenon that some people in Brookings, Oregon, would later call a miracle began in early July 2019, when the same monarch butterfly appeared in Holly Beyer’s yard almost every day for two weeks. Beyer recognized it by a scratch on one wing. She and a friend named it Ovaltine, inspired by ovum, for the way it encrusted the milkweed in Beyer’s garden with eggs. Each off-white bump was no larger than the tip of a sharpened pencil. Clustered together on the green leaves, they looked like blemishes, as if the milkweed had sprouted a case of adolescent acne.

Brookings sits on Oregon’s rugged coast, and squarely within the monarch’s habitat. Every spring and summer, several generations of butterflies breed, lay eggs, and die, each in the span of about a month. The last generation of the year is different. Come fall, rather than produce offspring, it migrates south. Beyer, a petite retiree with a trace of red in her gray hair, is part of a local group who promote butterfly-friendly gardening practices—planting native flowers, for instance, and forgoing pesticides.

Most female monarchs disperse their eggs as widely as possible, but for unknowable reasons, Ovaltine laid almost 600 in Beyer’s yard. Under normal conditions, fewer than 5 percent of monarch eggs survive to adulthood. Beyer wanted the marvel she had witnessed from her deck to have a happier ending. She snipped the laden leaves and brought them inside, to shield the eggs from wind, rain, and predators. Before long she had hundreds of caterpillars, then hundreds of butterflies. She released them into the wild, and Brookings, with a human population of just 6,500, was suddenly ablaze with orange wings. A person could be taking the trash out or crossing a parking lot and see a flash, like a struck match, from the corner of their eye.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: David Baltimore on the Mysteries of Viruses

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

I recently saw an estimate that if you took all the novel coronaviruses in the world (the actual viruses, not patients), you could fit them into a bucket no more than a couple of liters in volume. A huge impact has been wrought by a very small amount of stuff. The world of viruses is vast and complicated, and we’re still learning some of its basic features. Today’s guest David Baltimore won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery that genetic information in viruses could flow from RNA to DNA, establishing an exception to the Central Dogma of Biology. He is the author of the Baltimore Classification scheme for viruses, and has done important research in the role of viruses in diseases from AIDS to cancer. We talk about what viruses are, how they work, and the status of the novel coronavirus we are currently battling. David also has some strong opinions about public health and how we should be preparing for future outbreaks.

I recently saw an estimate that if you took all the novel coronaviruses in the world (the actual viruses, not patients), you could fit them into a bucket no more than a couple of liters in volume. A huge impact has been wrought by a very small amount of stuff. The world of viruses is vast and complicated, and we’re still learning some of its basic features. Today’s guest David Baltimore won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery that genetic information in viruses could flow from RNA to DNA, establishing an exception to the Central Dogma of Biology. He is the author of the Baltimore Classification scheme for viruses, and has done important research in the role of viruses in diseases from AIDS to cancer. We talk about what viruses are, how they work, and the status of the novel coronavirus we are currently battling. David also has some strong opinions about public health and how we should be preparing for future outbreaks.

More here.

Males Are the Taller Sex. Estrogen, Not Fights for Mates, May Be Why

Christie Wilcox in Quanta:

One of the most obvious physical differences between men and women are their average sizes. Men are, on the whole, taller. The standard explanation found in textbooks — sexual selection and male competition — goes all the way back to Charles Darwin: “There can be little doubt that the greater size and strength of man, in comparison with woman, together with his broader shoulders, more developed muscles, rugged outline of body, his greater courage and pugnacity … have been preserved or even augmented during the long ages of man’s savagery, by the success of the strongest and boldest men, both in the general struggle for life and in their contests for wives,” he wrote in The Descent of Man.

One of the most obvious physical differences between men and women are their average sizes. Men are, on the whole, taller. The standard explanation found in textbooks — sexual selection and male competition — goes all the way back to Charles Darwin: “There can be little doubt that the greater size and strength of man, in comparison with woman, together with his broader shoulders, more developed muscles, rugged outline of body, his greater courage and pugnacity … have been preserved or even augmented during the long ages of man’s savagery, by the success of the strongest and boldest men, both in the general struggle for life and in their contests for wives,” he wrote in The Descent of Man.

Essentially, were it not for men’s fiercely physical infighting for access to mates, all people would presumably be equally sized. Evolutionary psychology extends that argument to say that these biological directives underlie our behaviors; men can’t help but be aggressive and competitive, while women are by nature sneaky, conniving and choosy.

“There’s a lot of importance put on our differences in body size, as if that’s the keystone fundamental sex difference,” said Holly Dunsworth, a biological anthropologist at the University of Rhode Island. “This is what people think is fact, and if you don’t agree, they think you’re denying science.”

But in a recent paper in Evolutionary Anthropology, Dunsworth showed that the science points another way.

More here.

Andaz (Dilip Kumar – Raj Kapoor – Nargis)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R_Flxxs_uCY

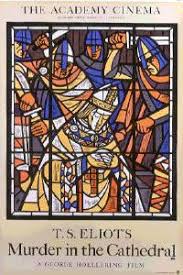

The Possibilities of Life-Writing

Lyndall Gordon at The Hudson Review:

It was these writers in other genres who opened up possibilities for biography with a shift of focus from public to private. Chekhov invites this with his sense that “every individual existence is a mystery.” The title of Eliot’s verse drama, Murder in the Cathedral, teases us with the popular genre of the murder mystery, yet there is no mystery of the usual sort: Archbishop Thomas à Becket’s murder in 1170 takes place onstage, and the murderers are visible: four identifiable knights who are hit men for the king, Henry II. The real mystery lies in the inner life: Becket’s capacity for self-transformation. This is a biographical play about a twelfth-century saint in the making, as he readies himself for martyrdom by sloughing off his public life together with the outlived temptations of his former worldliness and ambition.

It was these writers in other genres who opened up possibilities for biography with a shift of focus from public to private. Chekhov invites this with his sense that “every individual existence is a mystery.” The title of Eliot’s verse drama, Murder in the Cathedral, teases us with the popular genre of the murder mystery, yet there is no mystery of the usual sort: Archbishop Thomas à Becket’s murder in 1170 takes place onstage, and the murderers are visible: four identifiable knights who are hit men for the king, Henry II. The real mystery lies in the inner life: Becket’s capacity for self-transformation. This is a biographical play about a twelfth-century saint in the making, as he readies himself for martyrdom by sloughing off his public life together with the outlived temptations of his former worldliness and ambition.

more here.

In Search of Future Fossils

Lavinia Greenlaw at the LRB:

In Footprints: In Search of Future Fossils, David Farrier reaches into the past in order to envisage the deep future. This can only ever be an extrapolation of the present – our knowledge, experience, language and ideas – but Farrier is relaxed about this. His focus is on the way life has been recorded in the substance of the world, the ways we can trace human impact and the ways we, in turn, might be traced in time to come. He wrote this book before the pandemic struck, when past, present and future were relatively sturdy propositions. Now, the past has been uncoupled from a present that refuses to form. It’s not so pleasing to think of a mountain as a ripple in geological time when we feel like a ripple ourselves.

In Footprints: In Search of Future Fossils, David Farrier reaches into the past in order to envisage the deep future. This can only ever be an extrapolation of the present – our knowledge, experience, language and ideas – but Farrier is relaxed about this. His focus is on the way life has been recorded in the substance of the world, the ways we can trace human impact and the ways we, in turn, might be traced in time to come. He wrote this book before the pandemic struck, when past, present and future were relatively sturdy propositions. Now, the past has been uncoupled from a present that refuses to form. It’s not so pleasing to think of a mountain as a ripple in geological time when we feel like a ripple ourselves.

In looking to the deep future, Farrier considers ‘how we will appear to the people who may live in that world’. I wonder if the concept of fossils will mean anything to them.

more here.

When Gandhi Was Wrong

Rafia Zakaria in Baffler:

THE FIRST TIME MOHANDAS GANDHI, the leader of nonviolent protest against British rule in India, wrote to Adolf Hitler was in July of 1939. Gandhi was almost seventy. The world was, as it appears to be today, on the cusp of some huge transformation, although then, as now, the complete price of the change was unknown. “Dear friend,” Gandhi implored Hitler from behind a typewritten page, “friends have been urging me to write to you for the sake of humanity.” Hitler, the letter goes on to say, is the only “person in the world who can prevent a war which may reduce humanity to a savage state.”

THE FIRST TIME MOHANDAS GANDHI, the leader of nonviolent protest against British rule in India, wrote to Adolf Hitler was in July of 1939. Gandhi was almost seventy. The world was, as it appears to be today, on the cusp of some huge transformation, although then, as now, the complete price of the change was unknown. “Dear friend,” Gandhi implored Hitler from behind a typewritten page, “friends have been urging me to write to you for the sake of humanity.” Hitler, the letter goes on to say, is the only “person in the world who can prevent a war which may reduce humanity to a savage state.”

I can imagine Gandhi writing the letter, the humid air of an Indian July hanging heavy and oppressive, like the threat of war over the world. That first letter was barely over a hundred words, and it was never delivered. The British colonists who ruled India at the time minded Gandhi’s correspondence; they intercepted it well before it had any chance to reach Hitler. It is unknown whether Gandhi, an astute political strategist, knew this would be the case when he wrote the letter. He may have known that his audience was his own oppressors rather than the oppressors of European Jews. Whatever Gandhi’s motives, the appeal to Hitler was not new. The year before, American missionaries meeting with Gandhi pleaded with him to condemn Hitler and Mussolini, but he refused, insisting that no one, even these two fascists clearly uninterested in human dignity, was “beyond redemption.” Czechs and Jews were told to engage only in passive resistance, a sacrifice that would redeem them. Passive resistance failed to deliver either group, but Gandhi, for his part, never quite acknowledged this. (It was also not the only strategy they employed: consider the Warsaw Uprising of 1943, or the revolt at Auschwitz-Birkenau the following year.) Gandhi did write another, more vehement letter to Hitler, but this, too, was never delivered.

Gandhi got many things wrong about World War II. But in the days after George Floyd’s death, with protest ascendant, many reached for his prescriptions and other histories of nonviolent resistance, which present crucial questions about methods of opposition and defense. While there is much talk of the passive nonviolent resisters of old—Gandhi and his eventual disciple Martin Luther King Jr.—there is physical, psychic, and emotional violence being deliberately inflicted on the oppressed.

More here.

How deadly is the coronavirus? Scientists are close to an answer

Smriti Malapaty in Nature:

One of the most crucial questions about an emerging infectious disease such as the new coronavirus is how deadly it is. After months of collecting data, scientists are getting closer to an answer. Researchers use a metric called infection fatality rate (IFR) to calculate how deadly a new disease is. It is the proportion of infected people who will die as a result, including those who don’t get tested or show symptoms. “The IFR is one of the important numbers alongside the herd immunity threshold, and has implications for the scale of an epidemic and how seriously we should take a new disease,” says Robert Verity, an epidemiologist at Imperial College London.

One of the most crucial questions about an emerging infectious disease such as the new coronavirus is how deadly it is. After months of collecting data, scientists are getting closer to an answer. Researchers use a metric called infection fatality rate (IFR) to calculate how deadly a new disease is. It is the proportion of infected people who will die as a result, including those who don’t get tested or show symptoms. “The IFR is one of the important numbers alongside the herd immunity threshold, and has implications for the scale of an epidemic and how seriously we should take a new disease,” says Robert Verity, an epidemiologist at Imperial College London.

Calculating an accurate IFR is challenging in the midst of any outbreak because it relies on knowing the total number of people infected — not just those who are confirmed through testing. But the fatality rate is especially difficult to pin down for COVID-19, the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, says Timothy Russell, a mathematical epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. That’s partly because there are many people with mild or no symptoms, whose infection has gone undetected, and also because the time between infection and death can be as long as two months. Many countries are also struggling to count all their virus-related deaths, he says. Death records suggest that some of those are being missed in official counts.

Data from early in the pandemic overestimated how deadly the virus was, and then later analyses underestimated its lethality. Now, numerous studies — using a range of methods — estimate that in many countries some 5 to 10 people will die for every 1,000 people with COVID-19. “The studies I have any faith in are tending to converge around 0.5–1%,” says Russell.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Bread

Each night, in a space he’d make

between waking and purpose,

my grandfather donned his one

suit, in our still dark house, and drove

through Brooklyn’s deserted streets

following trolley tracks to the bakery.

There he’d change into white

linen work clothes and cap,

and in the absence of women,

his hands were both loving, well

into dawn and throughout the day—

kneading, rolling out, shaping

each astonishing moment

of yeasty predictability

in that windowless world lit

by slightly swaying naked bulbs,

where the shadows staggered, woozy

with the aromatic warmth of the work.

Then, the suit and drive, again.

At our table, graced by a loaf

that steamed when we sliced it,

softened the butter and leavened

the very air we’d breathe,

he’d count us blessed.

by Richard Levine

from A Tide of a Hundred Mountains

Bright Hill Press, 2012

Last day: 3 Quarks Daily Is Looking For New Monday Columnists

Dear Reader,

Here’s your chance to say what you want to the large number of highly educated readers that make up 3QD’s international audience. Several of our regular columnists have had to cut back or even completely quit their columns for 3QD because of other personal and professional commitments and so we are looking for a few new voices. We do not pay, but it is a good chance to draw attention to subjects you are interested in, and to get feedback from us and from our readers.

Here’s your chance to say what you want to the large number of highly educated readers that make up 3QD’s international audience. Several of our regular columnists have had to cut back or even completely quit their columns for 3QD because of other personal and professional commitments and so we are looking for a few new voices. We do not pay, but it is a good chance to draw attention to subjects you are interested in, and to get feedback from us and from our readers.

We would certainly love for our pool of writers to reflect the diversity of our readers in every way, including gender, age, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, etc., and we encourage people of all kinds to apply. And we like unusual voices and varied viewpoints. So please send us something. What have you got to lose?

You would have a column published at 3QD every fourth Monday. It should generally be between 1000 and 2500 words and can be about any subject at all. To qualify for a Monday slot, please submit a short resume or at least a one or two paragraph bio and a sample column to me by email (s.abbas.raza.1 at gmail.com) as an MS Word-compatible document, or a URL if what you want us to look at is available online, which I will then circulate to the other editors and we will let you know our decision by around mid-July. If you are given a slot on the 3QD schedule, your sample can also serve as your first column if it has never been published anywhere in print or online before. Feel free to use pictures, graphs, or other illustrations in your column. You will retain full copyright over your writing.

Please DO NOT submit more than one piece of writing, and also do not send the URL for a whole blog or website. I do not have the time to look through multiple postings. Select one piece of writing that you think is representative of the kinds of things you’d like to do at 3QD and just send that please. Also, please don’t send a good prose essay and then switch to writing poetry after we take you, or some other such thing. We are not looking for poets or fiction writers.

Several of the people who started writing at 3QD have gone on to get regular paid gigs at well-known magazines, others have written well-received books. Even those who have not, have written to us saying that it has been a uniquely rewarding experience.

The strict deadline for submissions is 11:59 PM New York City time, Friday, June 19, 2020.

Yours,

Abbas

Against Contrarianism

by Tim Sommers

Philosophy’s original contrarian hero was, of course, Socrates. He believed in Truth and the Good and refused to back down from the pursuit of the these – even when his life was on the line. He had no patience for ‘just whatever people tend to say about such and such’. The unexamined life, for him, was not worth living. And that examination requires being ready to question even your most cherished beliefs.

Philosophy’s original contrarian hero was, of course, Socrates. He believed in Truth and the Good and refused to back down from the pursuit of the these – even when his life was on the line. He had no patience for ‘just whatever people tend to say about such and such’. The unexamined life, for him, was not worth living. And that examination requires being ready to question even your most cherished beliefs.

Socrates also hated democracy and was against writing.

If you haven’t heard that second bit before, it’s not a euphemism. Socrates opposed reading and writing – the things that we are doing right now, you and I. Writing was the new big thing at the time. Their internet. Or to put it in more scholarly terms, Athens was transitioning from being primarily an oral culture to a literate one. But writing fails to capture the truth, Socrates said. It leads writers and readers to be forgetful and to “be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality”. (Which does sound a lot like the internet, come to think of it.) Anyway, presumably, this is why Socrates didn’t write anything down, and why we have had to learn most of what we know about him from Plato – who was also against writing, but then wrote a lot anyway. Really. A lot.

Although I haven’t done a scientific survey, academic philosophy still seems to have more than its fair share of contrarians. This is not an unmitigated good. Sure, when they are relentlessly pursuing what you think is the truth, contrarians seem great. But when they are arguing that we shouldn’t read and write, or that democracy is bad, well, maybe, not so great. Read more »